Background

An organisation's capability is delivered, almost without exception, by the team or set of teams that make up its structure. Consequently, effective team performance is critical to organisational success. A well-known incident highlighting the significance of team performance occurred on 3rd July 1988 when a United States Navy guided missile cruiser, the USS Vincennes, mistakenly shot down Iran Air Flight 655 over the Persian Gulf. Two hundred and ninety lives were lost. It was the air warfare team on board the Vincennes that had the responsibility for monitoring the airspace in the area where the ship was operating. This tragic event was attributed, in part, to failures in the interactions between members of the air warfare team on the USS Vincennes (Collyer and Maleki 1998). In the context of this book, the significant point about this incident was that the performance of the team involved depended on more than having skilled individuals in place; the critical issue was the way in which they worked together as a team. The United States Office of Naval Research responded to the incident by funding a seven-year research project, called Tactical Decision Making Under Stress (TADMUS), to investigate team performance. Notably, the improvement of team training was clearly identified in its objectives; such was the perceived significance of team training in relationship to team performance (Johnston et al. 1998). The purpose of this book is to provide a methodology for analysing team tasks to identify the critical aspects of team performance that need to be trained and to determine appropriate training solutions to enable teams to operate efficiently, effectively and safely.

Whilst few of us will find ourselves in a team involved in the decision-making process concerning firing a missile at an aircraft from a naval warship, most of us work in teams and encounter other teams both at work and in our everyday lives. As with the Vincennes incident, the issues that are involved in working successfully as a team are often highlighted either when things go wrong or when they go very well. Two such examples from everyday life came to light when the authors walked to a favourite restaurant for a lunch break whilst planning this book.

The first incident was observed as we walked to the restaurant. On the way we saw two bricklayers who were building a garden wall at the front of a house. The first few courses of bricks had been laid in a nice straight line and they were busy building the wall up to the required height. Since both could not work in the same place at the same time, they had made a plan to work at opposite ends of the wall and both work towards the middle. They had a piece of string stretched along the front of the wall as a guide so that the bricks could be laid level and in a straight line. As we were passing, the bricklayers were engaged in a free and frank exchange of views about how their task was progressing. The bricklayer at one end of the wall said to his colleague near the other end 'Your end of the wall isn't straight!', to which his colleague replied rather tersely as he looked along the wall, 'Well if you stopped leaning on the string it might help!' They had just demonstrated the need for communication, mutual performance monitoring and the provision of feedback between team members.

The second incident occurred at the restaurant itself. When we arrived our hearts sank, as a large party from a local company had arrived for a celebratory meal and had just ordered their meals. However, as we had always had good service in the past we elected to stay, hoping that we would be fed in a timely fashion despite there being a crowd ahead of us. Our dining experience was in the hands of two teams, the kitchen team led by the head chef and the front of house team led by the head waiter. In fact all went well. The large numbers of orders for some menu items meant that some items were no longer available by the time we were given menus. However, the kitchen team had communicated this to the front of house team and we were advised accordingly. Whilst the large party absorbed much of the teams' efforts, we were served hot, well-prepared food in a timely fashion, drinks were served promptly, and plates were cleared away soon after we finished eating. The large party appeared to receive a similar service. This suggested that both teams had a well-considered plan of action, that tasks were allocated effectively, and that communication and coordination was occurring both within each team and between the teams. The arrival of a large group dining together created a challenging set of conditions for the teams to work under. Not only did a large number of customers have to be served, everyone in the group dining together required their meals to be served at the same time. Equally, other diners expected to be served without delay. Therefore, the presence of a large group dining together causes the restaurant staff to experience a 'different sort of busy' to that of catering for a restaurant full of smaller groups of diners. The party of diners presented a more demanding requirement for synchronisation of team actions than that presented by simply having a restaurant full of smaller groups dining independently from each other.

Whilst these two examples are relatively small in scale, they serve to illustrate some of the complexities that are involved in carrying out team tasks. As team sizes increase and multiple teams become involved, these complexities amplify. Arguably, military organisations are faced with particularly demanding performance requirements and associated training requirements compared to those of civilian organisations. Whereas a civilian organisation tends to function in a clearly defined area of business in which it operates continuously, military organisations are required to be ready to undertake a wide variety of different tasks, of which many are only carried out when deployed on operations. The rest of the time they are in training. Furthermore, the exact configuration of the force required for a given operation will vary considerably depending on the nature of the operation itself. This complexity can be illustrated by considering the example of 1 Royal Irish Battlegroup as it prepared for and deployed to Iraq in 2003. The detail for this example is drawn from Colonel Tim Collins' account of his time in command of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Irish Regiment (Collins 2005).

In 2001 the Battalion had been deployed on peacekeeping duties in East Tyrone in Northern Ireland. On its return from Ireland in December 2001, the Battalion underwent training in the air assault role. After 10 months of training, the Battalion was deployed at short notice to an entirely different kind of task. They were to take part in Operation Fresco, manning Green Goddess Fire Engines to provide Fire and Rescue cover during the nationwide firefighters' strike in the UK during November and December of 2002. No sooner was this over, the Battalion received orders that it was to deploy to Iraq on Operation Telic as part of 16 Air Assault Brigade. At this point the Battalion was just over its established strength of 690. It was to deploy as the 1 Royal Irish Battlegroup with a strength of 1,225. This significant increase in numbers was due to the need to add additional units to the core Battalion to provide the required capability for the operation. These additional units included an artillery battery, an engineer squadron and 25 Air Naval Gunnery Liaison Coordinators from the United States Marines. The Battlegroup had less than a month to prepare for deployment. Colonel Collins was presented with a significant training challenge. Preparations included training at individual, team and collective (team of teams) levels. At the individual level, the soldiers had to be able to carry in excess of 100 lbs of equipment, survive in harsh conditions, and 'shoot straight ... at night, under pressure, and when exhausted and even frightened' (Collins 2005: 100). At a company level, Colonel Collins' requirement was that the basic building blocks of the advance to contact with the enemy, the set piece night attack and meeting the engagement had to be perfectly understood and practised such that the troops knew the actions to be taken in any situation. They had to be able to carry them out with minimum of instruction as there would be no time to think in a battlefield environment (Collins 2005).

In the remainder of this chapter we first look at team and collective training systems to get an understanding of their nature and complexity. This is followed by a discussion about Training Needs Analysis as a construct and the need for development of a methodology specifically focused on team and collective training. The chapter concludes with a brief introduction to the Team and Collective Training Needs Analysis Methodology and some suggestions for alternative strategies for reading the rest of the book.

Team and Collective Training systems

In this section we examine the nature of team and collective training and explore the complexities of the training systems required to deliver it.

Team and Collective Training

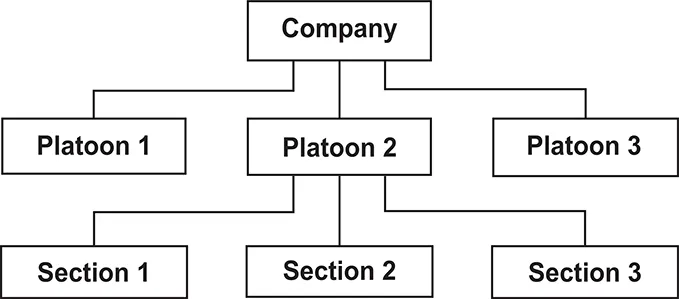

The structure of the training solution that Colonel Collins adopted in order to prepare his core infantry companies for deployment in the Battlegroup reflected the structure of the companies themselves. Figure 1.1 shows the generic structure of the infantry companies in the Battlegroup.

Figure 1.1 Infantry company structure

At the lowest level of aggregation are infantry sections. Each section is made up of a section commander, a deputy section commander and seven riflemen. The section commander and his deputy are responsible for the command and control of the section. The significance of this structure is that an infantry section can deliver significantly greater capability than can be delivered by nine infantrymen operating individually. For example, in order to neutralize an enemy gun emplacement the section can be split into two sub-teams: one team, led by the deputy section commander, to provide covering fire, whilst the other, led by the section commander, assaults the gun emplacement. At the next level of aggregation, three sections are combined to form a platoon under the command and control of a platoon commander and a platoon sergeant (the deputy). Platoon tactics, exploiting the coordinated action of three sections, enable more complex tasks to be undertaken. Similarly, at a company level, the employment of three platoons enables tasks of even greater scale and complexity to be undertaken. As the scale of aggregation increases, so does the command and control overhead. At a company level there is the company commander, his second in command, and a company sergeant major.

Training for each company began with individual training, with weapons training being a key component. This was followed by training at section level where section tactics were rehearsed. Once section training was completed, platoon level training was undertaken where the coordination of multiple sections undertaking platoon level tactics was practised. Finally, company level tactics were practised. Exercises took place both in the daytime and at night. This training sequence culminated in a live firing exercise on Sennybridge Training Area in Wales, conducted at company level. This exercise was supported by 105 mm light guns, 81 mm mortars and Milan wire guided missiles. Each of the companies in the Battlegroup had to advance under covering fire from medium machine guns and 0.5 inch heavy machine guns mounted on stripped down Land-Rovers (Collins 2005) and attack a wide range of targets.

The training solution which Colonel Collins adopted is representative of many collective training programmes in terms of the progression of training from individual to team and then aggregating teams together to train at more complex levels. Generally speaking the larger the team or collective organization then the greater the complexity of the tasks which it is required to undertake. This level of complexity is reflected in the complexity of the training system that is required to deliver suitable training.

Training System Components

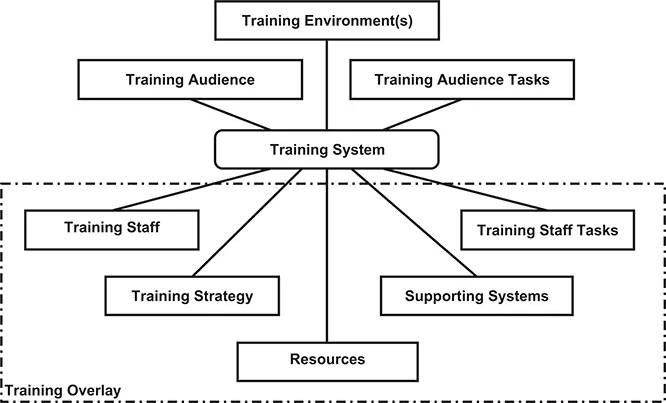

The key components of a training system are shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Training system components

Within a training system, the training audience undertakes a range of tasks in a training environment. This process is facilitated by the training staff undertaking their tasks in accordance with the training strategy and underlying methods, using a variety of training materials and assisted by supporting systems. In this book the term 'training overlay' is used to refer to the combination of the training staff, the tasks that they perform, the systems that they use to support the execution of their tasks, and the strategy and methods that they employ.

The complexities associated with each of the training system components for...