![]()

p.1

PART I

TEACHING CODING

![]()

p.3

CHAPTER

1 | WHAT IS CODING?

Tim Bell, Caitlin Duncan and Austen Rainer |

“CODE” AS A BUZZWORD

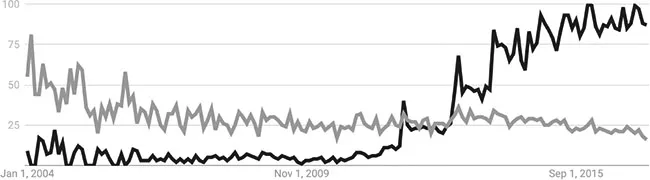

The idea of school pupils learning to “code” has been widely talked about in recent years, and the media discussions around this idea have almost redefined what we mean by “coding”. We can see increased public interest in coding by simply counting Google searches on the phrase “learn to code”, which increased rapidly from 2011 (shown by the black line in Figure 1.1), when industry, governments, and media started talking about this being an important aspect of children’s education. Traditionally this skill might have been referred to as “computer programming”; the grey line in the figure shows the corresponding number of searches for “learn to program”, which is being searched less often (relatively) over time.

The spikes in the “learn to code” queries (along with smaller spikes from “learn to program”) correspond to significant publicity events. January 2012 marked the release of the “Shut down or restart?” report from the Royal Society in the UK, which led to programming becoming a compulsory topic for all pupils in England; it was also when the Code.org organisation was announced and the first Raspberry Pi was being launched. The March 2013 spike corresponds directly to Code.org releasing their viral video “What Most Schools Don’t Teach”; and December 2013 was the month of the first “Hour of Code”, promoted by Code.org, which included a message from US president Barack Obama – although, interestingly, the verbs used in the president’s speech are “make”, “design” and “program”, not “code”.

The word “code” has also started appearing in the names of many organisations that have promoted learning to program publicly. With all this publicity, it isn’t surprising that the idea of “coding” has been raised in the public’s consciousness. In this chapter we explore what “coding” really is, and why it has had so much attention.

p.4

REFLECTION ACTIVITY

Is “coding” the appropriate term to use in your context for teaching programming?

As the trends in the Google searches show, “coding” hasn’t always been this commonly used to refer to computer programming, and in the world of computing, the term “code” has many meanings, making it highly ambiguous. One of the earliest applications of computers was during World War II for “codebreaking”, which is in the context of cryptography being used to hide secret messages. A somewhat broader meaning of coding developed as fundamentals of data representation (binary code) and information theory (including source coding and channel coding) developed to describe how data could be represented digitally. “Coding” can also refer to assigning codes to data to make it faster to enter into a computer, and “code” is used in a similar way to refer to the kinds of metadata that can be attached to information, such as the time and location of a photo. All of these meanings of “code” are about the information, and not the programs that process the information.

As compiled computer programs appeared, a distinction was drawn between “source code” (what a human would write) and “machine code” (a translated version that a computer could run). In the context of programming, traditionally “coding” would refer only to the last stage of the process of programming: translating the design of a program into a programming language (source code). Therefore in the broader context, “coding” is only a small part of developing a computer program.

The more recent use of “coding” to be synonymous with computer programming, while not entirely faithful to the historical use of the term, invokes a sense of mystery and excitement that has clearly served well in getting the public’s attention, and this informal use of the term has effectively changed its meaning. The word “code” has so many legitimate definitions that its meaning may catch the reader’s attention for a variety of reasons, and this can be useful for promoting the discipline of programming.

Even taking into account a wider meaning of “coding” or “programming”, they are not an end in themselves, and are part of a broader discipline around computational thinking and computer science, which is becoming more and more visible in education systems.

In this chapter we focus on the meanings typically intended when “coding” is discussed in the public arena around computing education. In kindergarten, primary, secondary and twelfth grade (for 17- to 19-year-olds), and in formal discussions, the general area in which coding is central is referred to using terms such as “computing”, “computer science” and “digital technologies”. In several European countries, “informatik” and the term “computational thinking” have also been adopted, to emphasise that there is a lot more to these disciplines than just coding.

To explore how these all connect, we look at these different aspects of “coding”:

p.5

■ programming: writing source code for software such as an app;

■ computer science: the broader discipline around how to write effective and efficient programs;

■ computational thinking: a term that captures the broader intentions of having “coding” in the curriculum by considering how pupils can use computational concepts for problem solving, even if the solution doesn’t involve implementation on a digital device;

■ software engineering: the discipline in industry that enables large software systems to be developed and maintained effectively.

We will see that the skill of “coding” touches on a range of issues, from more technical concepts (including the minimum understanding one needs to do something that could be considered programming) to social practice (such as how to develop software in a team environment, and how to design it in a way that is sympathetic to the needs of the end user). For the remainder of this chapter we will focus on the use of the word “coding” to mean “programming”, and will use the two terms interchangeably.

Although the term “coding” has many meanings, there are also several things that it is not. In particular, the term reflects a shift from broad terms such as “ICT”, “computer literacy” and “digital literacy” that had evolved in many school curricula to focus on preparing pupils to be users of computing technology, rather than enabling them to be makers or developers. A common complaint about traditional computer courses is that they have reinforced the role of a user at the mercy of the system they are using, rather than empowering them to change and create new systems (Bell, 2015).

PROBLEM-SOLVING ON COMPUTERS

The intention of programming is to solve a problem, and although coding is an interesting intellectual exercise in its own right, in an educational or industrial context we are generally concerned about the skills needed to develop software that is useful for people. Coming up with ideas for what might be useful is a creative activity, but it also needs to be built on a foundation that enables us to write programs that are reliable, efficient and usable. You don’t need to look far to find software that fails at least one of those criteria! These considerations and more are the ambit of computer science and software engineering, which are discussed later in this chapter.

In the meantime, as a concrete example to illustrate details of what programming is, but still maintaining a wider context, we use an example based on a “Computer Science Unplugged” activity. These are a free collection of activities for engaging pupils with the ideas in computer science without necessarily using programming. The CS Unplugged site2 includes a range of strategies for teaching coding, even one involving magic tricks based on error correction. For this chapter, we use a follow-up example, which detects whether an error occurs when a barcode (Universal Product Code – UPC) on a product is scanned. In passing, we note that the appearance of the word “code” in “barcode” is yet another use of the term that isn’t related to the meaning of coding that we’re focusing on!

The final digit on commonly used barcodes is chosen so that all the digits can be combined using a simple formula, and the total will be a multiple of 10 (e.g. 80 or 110, but not 83 or 92). This is done so that if any digit is read or typed incorrectly, or if two of them are transposed, this will usually be detected because the result isn’t a multiple of 10. This example exercises many key ideas from programming and computer science, but is fairly short, and is something that pupils may be familiar with from buying products in a shop. It is very important for efficient commerce: without it, barcodes would commonly scan as the wrong product without any warning, and both customers and shops would need to check dockets very carefully for such errors.

p.6

The “unplugged” version involves manually checking some barcodes. The following formula works for most commonly used codes (including EAN-8, EAN-13 and UPC-13), but not some eight-digit codes (UPC-E).3

To check a barcode, we multiply alternate digits by 1 and 3 respectively, starting at the right-hand digit in the code. In the example in Figure 1.2, the rightmost digit is 4, so that contributes 4 × 1 to the total; the second-to-last digit is 5, so that contributes 5 × 3, then 2 × 1, 3 × 3, 3 × 1, 8 × 3, 5 × 1 and 6 × 3. Adding these up gives 4 + 15 + 2 + 9 + 3 + 24 + 5 + 18 = 80. Because 80 is a multiple of 10, this indicates that we can be confident that the digits were read correctly.

If there had been an error while scanning or typing in the number, and suppose the leftmost digit was read as a 5 instead of a 6, the total would be 4 + 15 + 2 + 9 + 3 + 24 + 5 + 15 = 77. This is not a multiple of 10, and so the scanning would be rejected. If any single digit is incorrect, the sum cannot remain a multiple of 10 and the error will be detected. Another common error when typing digits is to swap two adjacent digits. For example, if the code had the first two digits swapped and was changed to 5683 3254, the total would be 78, and again an error would be detected.

Figures 1.3 and 1.4 show programs to implement this method (or algorithm) in Scratch and Python respectively. These coding languages have been chosen because they are commonly used programming languages in education. The programs have been written to correspond to each other closely, as well as to the algorithm for checking the barcodes described above. There are many different ways the task could have been programmed, and this highlights that there is not a single correct answer to the problem. As long as the program correctly applies the formula to find erroneous barcodes, it is a correct solution, even if not the...