eBook - ePub

EU Emissions Trading

Initiation, Decision-making and Implementation

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

EU Emissions Trading

Initiation, Decision-making and Implementation

About this book

The EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) has been characterized as one of the most far-reaching and radical environmental policies for many years. Given the EU's earlier resistance to this market-based and US-flavoured programme, the development and implementation of the EU ETS has been rapid. This novel approach to environmental regulation has the potential to affect not only greenhouse gas emissions in the EU, but also international strategies for climate change protection. This book investigates the origins, evolution and consequences of the EU ETS and offers significant contributions to the literatures on climate policy and EU policy making.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The EU was a leading sceptic to international emissions trading in greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the run-up to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Four years later, the European Commission proposed the world’s first international emissions trading system. The directive on emissions trading was formally adopted by the member-states in the Council of Ministers and by the European Parliament in October 2003. This directive introduced the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) for large industrial emitters of CO2 from 2005. The first round of implementation in the form of drawing up national allocation plans for the distribution/allocation of CO2 emission permits was mainly carried out in 2004. By 1 January 2005, the system was up and running. With the ETS, the EU had not only accepted the idea of emissions trading. From being a laggard, it had become a leader in emissions trading within a very short period of time. The EU Emissions Trading Scheme has been acknowledged as one of the most far-reaching and radical environmental policies in many years.

The aim of this book is to understand the EU’s turn-about and its consequences. Why did the EU change its position? How did it manage to establish the world’s first international emissions trading system so rapidly? What are the consequences so far? In essence, how can we explain the rapid initiation, decision-making and implementation of the ETS in light of the EU’s scepticism to including emissions trading in the Kyoto Protocol?1

The making and implementation of the EU ETS is politically and environmentally important for several reasons. First, it constitutes the major climate policy instrument of the EU, so the success or failure of the scheme will affect the extent to which the EU will be able to reduce its CO2 emissions and comply with its commitments under the Kyoto Protocol. Second, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme is the first international emissions trading scheme ever. As such, it represents an innovative political solution to one of the most pressing ecological challenges facing the earth today. Third, and for the same reason, the EU ETS represents a ‘grand policy experiment’ with ramifications extending far beyond the EU (see Kruger and Pizer 2004). How the Emissions Trading Scheme performs will have consequences for how the international climate negotiations can be brought forward beyond the initial commitment period (2008–12) of the Kyoto Protocol.

The development of the EU ETS is also theoretically interesting and challenging from a social science perspective. Different schools of thought offer different answers to the research questions above. One approach see EU policy-making and integration as mainly a result of interstate bargaining. According to this intergovernmentalist approach, the interests and preferences of the EU member-states are the key to understanding the EU ETS. The development of the EU ETS is compatible with an intergovernmentalist approach to the extent the member-states changed their positions, took the initiative and determined the design of the scheme. Another approach explains the EU ETS by pointing to the complexity of the actors and institutions involved at different levels of decision-making. The rapid development of the emissions trading scheme is more in line with multi-level governance to the extent it was the EU institutions, industry and environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) that changed their positions and strategies, took the initiative and determined the design of the scheme.

Intergovermentalist and multi-level governance perspectives emphasize EU-internal actors and institutions as key determinants for EU policy-making. But perhaps the main causes of the rapid development of the EU ETS lie outside the EU itself, in the interaction with the international climate regime. In line with this international regime approach, we would seek the explanation in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol’s commitments and provision for international emissions trading.

The idea of emissions trading has been – and to some extent still is – controversial and is by no means widely accepted (Lefevere 2005, 92). In the context of climate change, the concept has been challenged for being morally wrong and questionable with regard to equity (Ott and Sachs 2000). The essence of the moral/ethical argument is that emissions trading authorizes pollution, turning it into commodities that can be bought and sold. Equity concerns have been raised particularly with regard to developing countries and international emissions trading. The main argument here is that the richer industrialized countries can simply buy their way out of their obligations and thus maintain their disproportionate consumption of scarce resources. But even if emissions trading is accepted as an idea, transforming this idea into an instrument capable of reducing emissions of GHGs is by no means easy. Emissions trading cannot in itself reduce emissions or pollution: its effect depends upon how it is designed.

The logic behind a smoothly functioning emissions trading system is to encourage companies to decrease emissions by creating a dynamic monetary incentive so they can sell their allowances or credits to other larger polluters, and profit. Such incentives will not evolve if allowances are in excess of ‘real’ needs, or if monitoring and enforcement are inadequate. Conversely, a well-designed system based on strict caps and adequate monitoring, enforcement and compliance will, at least in theory, offer certainty of emissions reductions corresponding to the stringency of the cap. Unlike domestic trading schemes controlled by governments with authority to track and punish non-compliance, effective international systems are far more difficult to establish. Finally, even a well-designed system will not work if it is not implemented correctly by the participants in the system – which, in this context, means the EU member-states and by industry, its installations and operators.

These three challenges – acceptance of the idea, adoption and design of the system, and practical application – can roughly be related to three phases in the development of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme: policy initiation, decision-making and implementation. One central assumption is that the three explanatory approaches referred to above will have different explanatory power in these three policy phases. Another underlying assumption is that what happens in the initiation and decision-making phases will have important consequences for how the system is implemented and how well it will work in practice. The devil is not necessarily only in the details – it may very well also be in the major design decisions made along the way.

Below, we place the Emissions Trading Scheme within the perspective of EU climate policy. This brief history will show that the intergovernmental, multi-level governance and the international regime approaches all have their merits. The history of EU climate policy in general and emissions trading in particular cannot be fully understood without reference to non-state actors, member-states, EU institutions and the international climate regime.

A Brief History of EU Climate Policy2

References to climate policy began to crop up in European Community documents from the mid-1980s. It was briefly mentioned by the European Commission in 1985, and the Parliament adopted the first official EU document on the subject in the form of a Resolution in 1986 (Official Journal 1986). The Commission followed up with a 1988 Communication on ‘The Greenhouse Effect and the Community’,3 recommending further scientific studies and review of policy options. However, the Fourth Environmental Action Programme (1987–92) did not identify climate change as a priority issue.

In 1988 the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and international policy discussions intensified. During the spring of 1990, the Commission discussed the use of economic and fiscal instruments in environmental policy, including a specific energy/carbon tax. In June 1990, the European Council called for the early adoption of targets and strategies for limiting emissions of greenhouse gases. At a joint meeting of the Energy and Environment Councils in October 1990 (prior to the Second World Climate Conference), political agreement was reached on stabilizing EU CO2 emissions by 2000 at 1990 levels, on the assumption that other leading countries would take on commitments along similar lines (Skjærseth 1994). This agreement aimed at putting the EU in a leading position, especially in relation to the USA, and at influencing the negotiations on a UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The Commission immediately continued to flesh out a more specific climate policy package based on the following central elements:

• fiscal measures, particularly an energy/carbon tax;

• measures targeting the transport sector, including a maximum speed limit for private cars;

• measures to improve energy efficiency and the use of renewables, including a revitalization of the existing SAVE energy efficiency programme and a new ALTENER programme on renewables.

In light of subsequent policy developments, it is interesting to note that a spring 1991 version of this developing policy package also included a burden-sharing element, whereby certain countries with higher development needs – in practice, Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain – were to be given greater flexibility than the others (Ringius 1999, 139).

An autumn 1991 Communication from the Commission clearly expressed the ambition to act as a global leader at the upcoming June 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED).4 Just before UNCED, a Commission Communication5 outlined four main measures for the Council to adopt: a framework directive on energy efficiency (within the existing SAVE Programme); a decision concerning promotion of renewable energies (the ALTENER Programme); a directive on a combined carbon and energy tax, on the condition that such a tax was also adopted by ‘main competitors’ within the OECD; and a decision concerning a monitoring mechanism for CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions. However, the Council was not able to adopt any of these proposals prior to UNCED, whereupon Environment Commissioner Ripa de Meana resigned in protest.

The tax proposal led to some of the most ferocious lobby activity ever seen in Brussels. The fossil-fuel industry was able to water down the Commission proposal in a way that also contributed to erode consensus among the member-states (Skjærseth 1994; Newell and Paterson 1998). The UNFCCC was adopted at UNCED. It contained as a main element a loose commitment for industrialized countries, ‘individually or jointly’, to return to earlier levels of anthropogenic emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases by the year 2000.

After UNCED the Commission gave priority to getting the climate policy package adopted. Not surprisingly, putting the monitoring mechanism in place proved least problematic, and this was adopted in June 1993. The budgets for both SAVE and ALTENER were considerably reduced, and watered-down versions of both programmes were adopted in September 1993. However, getting the energy/carbon tax adopted proved even more problematic. Due to unanimity requirement in EU’s fiscal environmental policies, this was bound to be a controversial element of the package. From the very start, there had been considerable scepticism and resistance. For instance, the ‘cohesion countries’ (Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain) would accept a tax only in return for additional structural funding; France argued for a pure carbon tax in order to protect its nuclear industry; and the UK was opposed to any such tax at the EU level. As unanimity seemed increasingly unattainable and there was no sign of main OECD competitors establishing similar taxes, the idea of a common energy/carbon tax was downplayed towards the end of 1994.6 This – as well as the slashing of the SAVE and ALTENER budgets – should probably be seen in light of the more general shift in EU integration trends in the early 1990s towards ‘subsidiarity’ and ‘the limiting of EU powers’ (Collier 1997).

In the preparatory process to the first UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (CoP) to be held in Berlin in 1995, the EU agreed to aim for the launch of negotiations on a new protocol with strengthened commitments, to be concluded by the time of the third CoP, in 1997. This was also very much the outcome of the first CoP (the ‘Berlin Mandate’). The Ad Hoc Group on the Berlin Mandate (AGBM) was established as a forum for discussions and negotiations towards the new protocol.

Already by the end of 1995, the EU position was to combine a target for the Union as a whole with an internal burden-sharing agreement. However, reaching agreement on a position for both a common target and an internal sharing proved difficult, and several EU countries, including Germany, tabled their own protocol proposals within the AGBM. In order to meet the March 1997 final deadline for tabling protocol proposals (including the development of a specific burden-sharing formula), under the leadership of the Dutch Presidency, an agreement on a 15 per cent joint target and a specific burden-sharing formula for differentiated targets for individual member-states amounting to an overall reduction of 9.2 per cent by 2010 was hammered out in early March (Ringius 1999). This enabled the EU to stand out as the most ambitious by far of the major actors.

In Kyoto in December 1997, the EU spent much time on internal coordination and trying to stand up against US ideas on a protocol based on flexible mechanisms such as international emissions trading. The EU succeeded in getting a protocol adopted with strengthened commitments and with the USA on board, but the more specific design of the protocol has a distinct US flavour. Three flexible mechanisms became central ingredients of the Kyoto Protocol: emissions trading, Joint Implementation (JI), a Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The EU’s own target became an 8 per cent reduction of greenhouse gases (GHGs) by 2008–12 from 1990 levels. Furthermore, similar to other parties to the Protocol, the EU should make demonstrable progress in achieving its commitment by 2005.

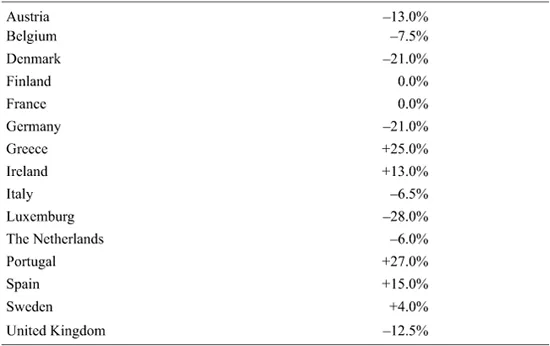

After Kyoto, both the Community and the individual member-states had quantitative targets. However, the Kyoto outcome deviated from the EU’s assumptions underlying the 1997 Burden-sharing Agreement, as the target was less ambitious. The number of gases had been expanded, and there was a commitment period from 2008 to 2012 rather than a single target year of 2010.7 The 1997 agreement was hence revised and transformed into a Burden-sharing Agreement in June 1998, with the 8 per cent reduction commitment divided among the EU member-states as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Member-state goals under the 1998 Burden-sharing Agreement

The Burden-sharing Agreement became legally binding in 2002. Later it came to serve, together with the Kyoto commitments, as the foundation for allocating emissions allowances under the EU ETS.

At least from the perspective of the Commission, there was a clear need for new policy instruments at the community level to meet the Kyoto commitments. Although the EU was well under way to achieving stabilization by the 2000 target, it was clear that this was very much due to the ‘dash-to-gas’ in the UK, and reunification effects in Germany.8 Efforts to dress up the carbon/energy tax as an energy tax in 1997 did not help, as key European industries and member-states like Spain and the UK continued to mount vociferous opposition. ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Analytical Framework

- 3 Development of the EU ETS

- 4 Initiating EU Emissions Trading

- 5 Deciding on EU Emissions Trading

- 6 Implementing EU Emissions Trading

- 7 Conclusions

- References

- Annex I

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access EU Emissions Trading by Jon Birger Skjærseth,Jørgen Wettestad in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.