- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

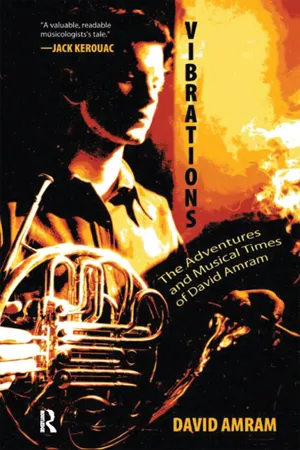

David Amram has played and rambled and galloped and staggered through a remarkably broad sweep of American life, experience, and creative struggle. The Boston Globe has described him as "the Renaissance man of American Music." Amram and Jack Kerouac collaborated on the first-ever jazz poetry reading in New York City in 1957 as well as the subsequent legendary film Pull My Daisy in 1959, combining Amram's music with Kerouac's narration. Amram, honored as the first Composer-in-Residence of the New York Philharmonic, has composed more than 100 orchestral and chamber works, written two operas, and has collaborated with Leonard Bernstein, Dizzy Gillespie, Lionel Hampton, Charles Mingus, Dustin Hoffman, Thelonious Monk, Willie Nelson, Nancy Griffith, Johnny Depp, and more. Vibrations is the story of one boy's adventures growing up on a farm in Pennsylvania, working odd jobs, misfitting in the U.S. Army, barnstorming through Europe with the famous Seventh Army Symphony, exiling in Paris, scuffling on the Lower East Side, day-laboring-often down but never out-finally emerging as a major musical force. With its stage-setting foreword by Douglas Brinkley and a new afterword by Kerouac biographer Audrey Sprenger, this new edition is not to be missed.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

WHEN we were living at my grandmother’s house in 1936 I remember a sound that used to float upstairs while I was supposed to be asleep. It was like boxcars bumping together as a great steam locomotive pulled them slowly from the rail yard. This clanking and banging was my father, playing in the quiet of the night when all of us were supposed to be asleep. There was a wonderful old rosewood Steinway in my grandmother’s living room, and as he would practice I would listen, fascinated as he attempted to play through the first movement of a Mozart sonata or Brahms symphony arranged for four hands. He couldn’t play more than one chord without getting stuck. Sometimes after finishing a measure, he would go back again and start over. But somehow that sound of going back and forth and gradually getting to the end like a mountain climber who keeps slipping and sliding but still makes it eventually to the top—that was to me the first sound of music.

I remember going down to the creek near Shoemaker Road and dropping my blue bonnet in the water. When it floated away, I hung on to the branch of a tree and yelled “Help”—a word my sister had read aloud from a comic book. Sure enough, help came even though I wasn’t sure what it meant. I also have vague recollections of being spanked for hitting my sister over the head with a toy truck when she wouldn’t let me climb on top of her snowman, great Passover dinners with hot steaming mountains of food and me trying to learn the speech of the youngest son. Of all of these recollections, though, none is as strong as the impression of my father’s playing.

On my sixth birthday my father bought me a bugle. My grandmother and grandfather, my aunt and uncle who lived across the way and all their children were there. It was the first and last happy scene I can remember. Within the next three years my grandfather, his son and my aunt’s son were all to die. But at this time our whole family was together and the great feeling of tribal unity was terrific.

When dinner was over, I was allowed to open my three presents. The first was some kind of terrible colored necktie like the ones worn in Our Gang comedies. The second was a sweater, with a note beautifully written by my grandmother in her painstaking, clear handwriting, telling me how glad she was for me to be having a sixth birthday. The third present was wrapped up in something a little larger than a shoe box, tied with a slick, wide red multi-bowed Woolworth-style ribbon. I ripped it open, went through all the shredded-paper filling and saw to my amazement and delight a regulation Boy Scout bugle. Its wonderful brass shine thrilled me before I even heard a note. As I reached out to touch it my father picked it up and proceeded to play it for half an hour. Possibly because of his mustache, which got tangled in the mouthpiece, or more likely because he had not played a bugle since World War I, the sound he produced was not one of overwhelming beauty. When at last he handed me the bugle I tried it for about thirty seconds and was able to make a sound with relative ease. This first experience was the beginning of a lifelong addiction.

Because my eight-year-old sister was sick and needed to be in a better climate, my mother took both of us to Pass-a-Grille, Florida, for the winter of 1936 and the spring of 1937. It was not what you would call a tropical paradise, but we loved it. We lived in a little ramshackle bungalow with a screened-in porch, thorny shrubbery outside and several nests of scorpions under the latticework. Across the street lived a man named Lester Jefferson, who—between bouts of gin and deep despair over the ruin the Depression had brought to his life—put together wonderful collections of seashells, which he’d meticulously mount on white pasteboard. My sister and I would watch him for hours. He would paste them together and notate them carefully with the Latin as well as the English names. Then he would get dressed up and, in spite of a case of the shakes, go out and try to sell them. But no one would buy, so he’d give some of them to his friends, go back to drinking and eventually smash the rest to pieces. There was also someone in the neighborhood who had a powerful singing voice. As my sister and I would lie awake at night listening to the ocean and hoping that no scorpions would sting us when we fell asleep, we could hear his whiskey baritone filling the air.

In those days Florida had a great atmosphere of nonchalance about everything. When my mother asked my teacher how I was doing, she said, “He’s right smaht, but he cain’t read yet.”

I wanted to take music lessons at school but there was no music department and no musical instrument except an old beat-up piano that was never played. I thought it was probably just a prop with no insides. For some reason, however, I had a vision of playing the piano and being a composer, even though I wasn’t sure what a composer did. My sister would read me the names of composers from piano music we had. They were beautiful editions with yellow covers, green borders and green letters. She told me that they were Bach and Beethoven and Brahms and other composers whose names I recognized because my father had plowed through their music.

I didn’t learn much in school, but I had a wonderful time. Before lunch hour every day we used to go swimming and once we went to St. Petersburg and watched the old people play shuffleboard. We were taken out on a boat by an incredible sea dog with one arm who kept showing us his stump. He proudly told us that a shark had leaped out of the water and bitten off his arm before he knew it.

The only artistic event I can recall from my school years in Florida was when I appeared in a school play. Pop came all the way from Philadelphia to see me in the role of a yellow flower, and my sister as some kind of post-Crustacean sea creature. We also put on our own little show for him, which included a wild dance through our homemade orange grove. Because we had no real orange trees, my mother bought a tremendous bag of oranges for fifty cents and we tied them with green string to a scrofulous old tree. As my father arrived, exhausted from his trip down to our seaside slum, my sister and I went into this welcoming pageant. He wasn’t too impressed with this, but my role as a flower in the school play interested him enough for him to take a picture of it, which I still have.

In the late summer of 1937 we moved from Florida to the large farm in Feasterville, Pennsylvania, my father, uncle, aunt and my grandfather had bought in the beginning of the 1920s. My father had a degree in agriculture from Penn State University and had been a farmer for four years before going back to school to study law and become a teacher. His brother had also been a farmer but then left Feasterville to be a radio operator on a Grace Line ship and later take every other kind of job mentionable. But our land was still in good shape, even though it was impossible to make a living with that size farm anymore.

As soon as my sister and I moved in, we never wanted to leave. There was a whole pine forest, which my father and mother had planted when they were first married. There was a cemetery off in the distance and some fields of corn and alfalfa which my father farmed and a meadow where our few cows grazed.

From the time I was seven I began milking the cows and taking piano lessons. After a few months of milking, my hands got a great deal stronger, which impressed my piano teacher very much. She once asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. “A farmer,” I told her. I was fascinated with music, but even though I was only seven I could already milk cows and even began growing my own vegetable patch. I also knew about planting crops, chopping wood and clearing land. I used to ride on the back of the tractor with my father and knew how all of that worked too.

But my piano teacher seemed disturbed by this.

“You can’t be a farmer,” she said.

“Who says I can’t?” I replied.

“Because no Jewish boy can ever be a farmer, they’re not meant to be.”

“Well, my father was a farmer for four years, and he still farms part-time.”

“Well, he doesn’t count,” she told me.

Her teaching was more logical than her nonmusical moments. She taught my sister and me the Diller-Quail Beginners’ Piano Book, but because we had heard our father struggle through much more complicated music we found these children’s pieces amusing but boring. After playing through them for a while we would collapse into laughter, then begin improvising our own music.

Shortly after I began piano lessons there was a musical demonstration for my second grade. We were told that if we wanted to study any of the instruments shown, the school would provide them and give us lessons. I had no idea who the two demonstrators were, but they were fabulous showmen. They looked like Laurel and Hardy and in addition to playing the instruments they had a fantastic vaudeville-inspired floor show, complete with comic routines such as playing the instruments backward or upside down, swapping them back and forth and even using two at a time. This was irresistible for any second-grader, especially in the days before television. Such novelty acts could only be imagined while listening to Major Bowes’ “Amateur Hour,” a radio show that wasn’t too often of too high musical caliber. When the two gentlemen began playing the trumpet, I knew this was the instrument for me. I began studying and took lessons at the Music Settlement School in Philadelphia whenever we made one of our occasional trips into the city. My teacher had large lips, thick glasses and a huge beaked nose. He gave me all kinds of ominous warnings of how I would lose my lip if I didn’t practice properly and how I must always warm up at least half an hour a day and forty-five minutes before symphony concerts. Since I was only eight years old I didn’t feel that any of these dire predictions of my demise in the music world particularly applied. But I was eager to learn, so I listened not only to his warnings and worries but also to his trumpet playing, which was excellent. I used to play with the mouthpiece a little to the side of my mouth with one shoulder hunched up, which upset my father. I remember him shouting at me to play sitting up straight without arching my body.

Shortly after I began my trumpet lessons, I went with my family and relatives to hear a children’s concert at the Academy of Music with Leopold Stokowski conducting. “Peter and the Wolf” was one of the pieces performed and I remember a large police dog on the stage which represented the wolf. When William Kincaid played the celebrated flute solo, the dog began to bark. More important, when the three French horns played the menacing warning of the approaching wolf, I almost fell out of my chair. I remember a sensation going through my entire body at the sound of these three magnificent French hornists playing together. From my seat up in the peanut gallery I watched them stand up to bow, the spotlights reflecting kaleidoscopic colors off their shiny instruments, and I knew that someday I wanted to play at least a note on one of those exotic, wonderful-looking horns.

I got my chance about three weeks later in the school music room. While everyone was out to lunch I crept in and took out a French horn sitting in the closet. I noticed that instead of fingering with the right hand you fingered with the left; and rather than having trumpetlike valves, the horn had rotary valves with stemlike steel plates that were depressed to make the valve move. After I played two or three notes, I was surprised to discover how easy it was to make a sound but how hard it was to produce a really clear note. As I was experimenting I felt a sharp whack on my behind. The teacher had come back early from lunch and caught me playing an instrument that was not assigned to me.

“Don’t you do that again or you’ll be in trouble!” she shouted.

Because I liked her, I didn’t offer any resistance. Guilt-ridden at being caught in this lascivious act of passion, I put the horn back in its case and crept out of the room to eat my fried-egg sandwich in shame. It was not for years that I got to play the French horn again.

It was during this time that I discovered jazz by listening to big band broadcasts on the radio. This was about 1938, when swing bands were in their full flower. Anyone who watches old movies on television knows that band leaders of the thirties were like minor movie stars. Harry James, Gene Krupa and Cab Calloway were as familiar to kids then as the rock stars are today.

I was always interested in different kinds of rhythm. I would sit around playing on toy drums for hours. One sound I’ll never forget was the fantastic syncopated rhythms that our heating system used to make. It sounded like one long drum solo. I remember playing along with it, lying on the floor, wailing away with my ear pressed to the heater, and my knuckles on the grating. This began my informal rhythmic studies and I think somehow gave me a foundation for a rhythmic sense that I never lost.

When I was nine, there was a man who worked on our farm occasionally who also had his own gospel group. He had two sets of postcards that he would always show me. One was a set of carefully lettered pictures of him announcing services where he and his gospel group were performing. The other set was a fantastic collection of pornographic studies. Although the latter group made a far greater impression on me, seeing I was only nine years old and my imagination was somewhat limited in these areas, I do remember being interested in some of the songs that he and his gospel group played. Sometimes he brought his guitar to work and I used to play along with my trumpet. We mostly played old-timey blues, though I didn’t know then they were called that. I was familiar with the melody for “Frankie and Johnny,” which is based on the blues pattern, so he showed me, rather informally, that I could use the same chords to play a lot of blues songs. This is hardly revolutionary news, but in 1939 there weren’t many opportunities for nine-year-olds to have such educational jam sessions, especially in rural areas. We worked up quite a repertoire and I might still be playing with him today except that shortly after that he was arrested for armed robbery. I remember how terrible I felt, because he had always encouraged me and he had a great musicality that I’ll never forget.

In 1939 I gave my first concert performance with another budding trumpeter, Bobby Sye. He was a good, quiet boy who wore the kind of cap that professional golfers used. Whenever we visited his house to practice our trumpet duets, his mother would wash his face, clean his nose and invariably tell me, “I don’t like that Roosevelt one bit, we can’t have a man for President who cannot stand up on his own feet.” Bobby would look embarrassed, but once she had finished her tirade against the Democratic Administration she would go back to her housework and let us play away. After we rehearsed a twotrumpet version of “Santa Lucia” and some march arrangements for two trumpets we would sneak out to the back of an old building that had once been a toolhouse, wind up a beat-up Victrola and listen to Harry James and Ziggy Elman records. This was the kind of music that the two demonstrators had played part of the time and this was how we really wanted to play. But we didn’t know either where to get the music or how to play it.

There was one trumpet player in our school band who tried to play this way, but the music teacher always slapped him whenever he began to improvise during the hack music we were supposed to grind out during basketball or football games. Our raggedy band of students from the first to twelfth grades was supposed to cheer our team on, but sometimes we didn’t have as many as eleven boys really able to play football and often their uniforms were homemade. We were always excited, though, because there was a chance our friend might do a little improvising before he was knocked down by our music teacher, who was also the band director.

When Bobby and I found out that the recital was coming up soon, we were scared to death since we would have to play in the auditorium in front of all the other students. So we began practicing like mad. On the day of our concert we were nervous all through classes. We even avoided getting in fights during recess, and when the classes were finally over, Bobby confessed to me, “I don’t feel too good.”

“I don’t either,” I said.

“Well,” he said, “that’s O.K., it won’t sound any more lousy than the other kids.”

Night came and we waited nervously for our big chance. Finally it was time for us to go on. We walked onstage with our trumpets and our music stands and both of us almost fainted before we even got to the center of the stage. Spotlights nearly blinded us. Petrified, I peered out into the auditorium, hoping no one would see me trying to recognize people in the audience. I couldn’t see anything except a huge black hole like the ocean at night, but the rumble from the people out there was terrifying, like some gigantic sea monster. I had the feeling that as soon as I missed a note, some primordial jaws would come and snap us both in half.

Finally, after shuffling the music and fumbling with the mouthpieces of our trumpets and getting the water out of the instruments and trying to get in tune, we were ready to begin. The rumbling, which by this time sounded like the North Atlantic during a full-scale hurricane, suddenly stopped and that was even more frightening. Bobby was shaking so hard he could hardly put the trumpet to his lips. I was sure if I didn’t begin right away I was going to pass out, so without waiting for Bobby, I signaled with my trumpet and started right up. The noise that came out was amazing. It sounded as if it were coming from beneath a pile of mattresses about a mile away, a tiny, pinched, warbling, quavering, nervous, frightened squeak. Every note sounded as if it were being shredded. Bobby joined me and he sounded even worse.

But when we finished “Santa Lucia” at long last, there was thunderous applause. We looked at each other in absolute astonishment. It was all we could do to control ourselves and not break down in hysterical laughter. Despite how terribly we had played, the audience seemed to love it. So we broke right into our final number, a march that sounded a little better. This really brought down the house, which we ultimately realized consisted of about thirty-five people, most of them parents, brothers and sisters of the performers, all dressed in coveralls, all beaming with happiness. When we had finished and the lights were about to go out, I saw my mother’s ecstatic face smiling with pride. My father, however, had a kind of half-smile with his eyes up to the ceiling as if to say, “God, what that sounded like.” Still, Bobby and I managed to make our public debut as trumpet players and we now felt that anything was possible.

Shortly after this concert, I found out what it meant to be a Jew in rural Pennsylvania, 1939. I was the only one in the school (my sister Marianna didn’t seem to count) so naturally I was the logical choice to be beaten up and abused every day by my classmates. This was because many of these kids had parents who were part of the German-American Bund, a neo-Nazi organization. My father had gone through the same experience in Germantown, Pennsylvania, where he had been brought up, so he prepared me with an attitude that was as much Christian as it was Jewish. He told me that these were children of ignorant parents, that they knew no better and that I should understand that because of the Depression these people had to find some kind of scapegoat for their misery. I was the only child in school whose family owned a car, so I became the symbol of the capitalistic Jew. My father also told me to choose my friends among people who were not ignorant. Still, each day at recess I had to fight.

My grandfather had taught me Hebrew and my father ran a little Sunday school in our farmhouse for the children in the area who were Jewish and some relatives of ours in Philadelphia who were Jewish but who weren’t so anxious to acknowledge it. We learned that part of the tradition ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword by Douglas Brinkley

- Preface to the 2001 Edition

- Prelude

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Epilogue

- Afterword

- Selected Discography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Vibrations by David Amram in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.