- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Designing Future-Oriented Airline Businesses

About this book

Designing Future-Oriented Airline Businesses is the eighth Ashgate book by Nawal K. Taneja to address the ongoing challenges and opportunities facing all generations of airlines. Firstly, it challenges and encourages airline managements to take a deeper dive into new ways of doing business. Secondly, it provides a framework for identifying and developing strategies and capabilities, as well as executing them efficiently and effectively, to change the focus from cost reduction to revenue enhancement and from competitive advantage to comparative advantage. Based on the author's own extensive experience and ongoing work in the global airline industry, as well as through a synthesis of leading business practices both inside and outside of the industry, Designing Future-Oriented Airline Businesses sets out to demystify numerous concepts being discussed within the airline industry and to facilitate managements to identify and articulate the boundaries of their business models. It provides material from which managements can set about answering the key questions, especially with respect to strategies, capabilities and execution, and pursue an effective redesign of their business. As with the author's previous books, the primary audience is senior-level practitioners of differing generations of airlines worldwide as well as related businesses. The material presented continues to be at a pragmatic level, not an academic exercise, to lead managements to ask themselves and their teams some critical thought-provoking questions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Designing Future-Oriented Airline Businesses by Nawal K. Taneja in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Rethinking the Airline Business: Where Do We Stand?

The Director General and CEO of IATA, Tony Tyler, described “the natural state of the airline industry as being in crisis, interrupted by brief moments of calm.” Thus, while change, or even its rate, is hardly a new phenomenon within the airline industry, uncertainty, risks, a sense of urgency, and, particularly, the need to experiment and iterate are now becoming much greater for all segments within the global airline industry. From this perspective, while many airlines have been changing their business models to adapt to the marketplace, the changes, with very few exceptions, have been at the incremental level rather than at the transformative level. On the other hand, at least, the 12 challenges mentioned in this chapter are mandating airline managements to go beyond incremental changes and to rethink, realign, and, possibly even, reinvent, their businesses by gaining insights from both inside and outside the airline industry. Although growth has varied by region, the global airline industry has been, and continues to be, a high growth industry. To continue to capitalize on this growth, while facing the challenges of new entrants that are rapidly adapting to the changing landscape, the established airlines need to move at a much faster rate of transformation.

Business Model Transformation Spectrum

At what point on the business model transformation spectrum should an airline be—incremental, or transformative, or somewhere in between? Consider some examples at the two ends of the spectrum. Two examples of incremental strategies (of short term nature) are: (1) changes in capacity to match demand, and (2) some new fee-based services. Two recent examples of transformative changes (longer term strategies) are: (1) pursuit of mergers to increase economies of scale to reduce cost and economies of scope to increase market share, and (2) virtual operations. Incremental changes, while being relatively easier, are not going to address the 12 challenges (discussed below) facing the industry, other than for airlines with special circumstances, such as, government protection (for instance, Air India) and special niche markets (for instance, British Airways at Heathrow). Even the assumption of “too big to fail” has proven to be invalid. Inertia and scale alone (“too big to fail”) did not prevent American Airlines and Japan Airlines from filing for bankruptcy. The other two circumstances may enable, at least in the foreseeable future, some airlines to continue to work with incremental changes.

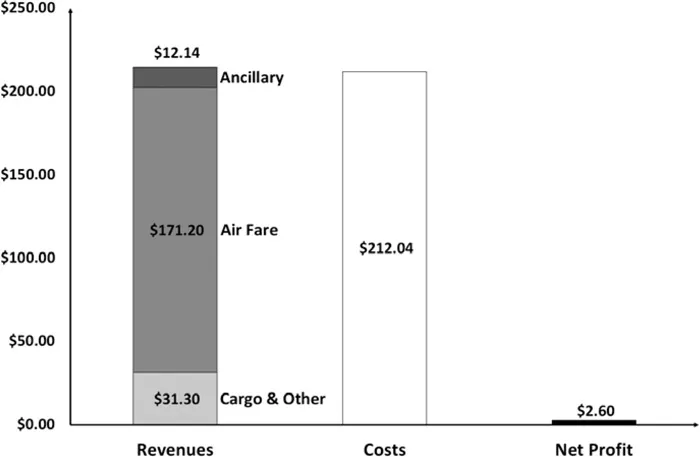

Let us examine the need for realignments of airline businesses at the transformative level from a more fundamental perspective shown by the information in Figure 1.1. On a worldwide basis, in 2012 airlines earned a mere US$2.60 in net profit on each departing passenger on a revenue base of more than $200. How does this figure compare with the profit margins on a cup of Starbucks coffee or a bottle of Coca-Cola in a restaurant in Europe? Shouldn’t airline shareholders expect a far better financial performance given the required level of investments and the level of risks? Assuming the answer to be yes, managements need to adopt a transformative vision and culture, supported by disruptive technologies (relating to information, analytics, and mobility), dramatic changes in processes and functions, as well as insights from the best practices from both inside and outside the industry to dramatically improve the margins. From this perspective, a few airlines are beginning to “see” that the future shape of the airline business is at a point of inflection—just as when American, in the very early 1980s, used the then big data and analytics to analyze the reservations and booking data to undertake what was at that time known as “yield management.” It is this process that enabled airlines to match low fares offered by low cost airlines and reserve seats for high paying passengers booking closer to the flight departure times. Now, big data, analytics, and digital technology (including mobile) can be used to redesign the airline business, just as Uber transformed the traditional taxi business.

Figure 1.1 Costs, revenues, and profits on a typical flight

Source: International Air Transport Association

Need for Realignment

Leaving aside the historical poor margins, here are at least 12 other considerations supporting the need to redesign the airline business at various levels.

1. Competition is now no longer limited to traditional peers. New players from within the airline business are succeeding with new business models, attacking areas considered to be critical for traditional airlines—for example, (1) feeder traffic from short and medium haul markets, specifically in Europe, and (2) emerging hubs, at such alternative airports as Panama, Istanbul, Addis Ababa, Dubai, Guangzhou, and Honolulu. Moreover, there is room at the low end for competition from even newer types of airlines given that it is relatively easy to start an airline (with barriers to entry being relatively low even though they continue to exist).

2. The relatively newer generation of global airlines, such as those based in the Persian Gulf, and to some extent those based in China, are proving that they not only have staying power, but that they intend to change the historical airline industry landscape. Etihad Airways is not only growing its own capacity, but it is also implementing truly strategic relationships with existing airlines—some through codeshares (such as with Air France–KLM) and some through equity positions (such as with Aer Lingus, Air Berlin, Air Seychelles, Darwin Airline—renamed as Etihad Regional, Jat Airways, Jet Airways, and Virgin Australia).1

3. Investors in the airline industry are no longer mostly “day traders.” Many investors now have a much longer term orientation. This change is requiring airline CEOs to focus much more on the quarterly and annual financial performance.

4. Lower cost airlines are finally finding the ingredients to succeed in intercontinental and business travel markets, validated by the operations of Jetstar and Virgin Australia. This phenomenon will proliferate as airlines get new aircraft such as the Boeing 787 and the Airbus 350 (with the right cost performance features) and as they develop new operational capability. Norwegian Air Shuttle, for example, uses a new operating certificate (Norwegian Long Haul AS), the fuel efficient Boeing 787 (with 291 seats in a two-class configuration) and non-Norwegian-based, lower cost crews working out of Bangkok to operate in such markets as Bangkok–Oslo–New York.

5. Niche airline service providers are beginning to emerge around specific segments of the market to position their products and services to match the demand. For example, the US-based Allegiant is a travel company that happens to operate an airline. In Brazil, Azul Brazilian Airlines has been extremely successful in providing service in noncompetitive markets. In Iceland, Icelandair is achieving profitable growth by using its Reykjavik hub to transport passengers between North America and Europe. In Mexico (VivaAerobus) and in Colombia (VivaColombia), are ultra low cost airlines that are competing with buses in medium and long haul markets.

6. Increasing liberalization of air transport markets, particularly in the Asia Pacific region, is enabling new-generation airlines with profoundly different business models to be serious threats to mature airlines. AirAsia Berhad, for example, has been able to find creative ways to integrate its resources to set up operations throughout Asia.

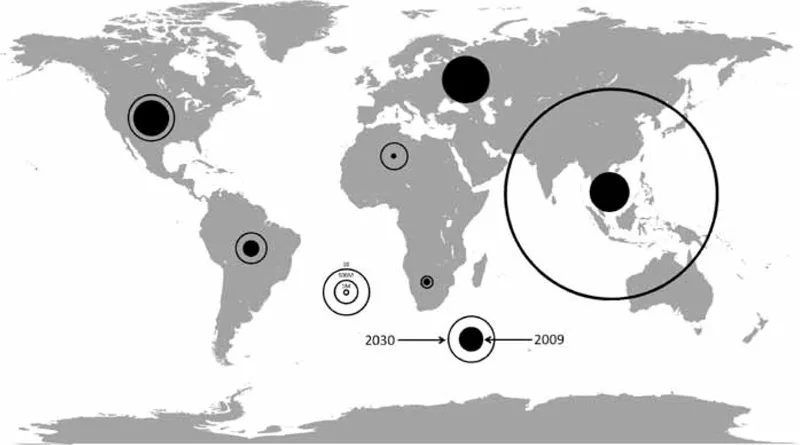

7. A shift in the economic power from the Atlantic to the Pacific is creating unprecedented opportunities for airlines. Figure 1.2 shows the expected growth in the middle classes—segments with the means to purchase tickets to fly on airplanes in Asia compared to other global regions. The actual and expected rise in lower fare travel warrants a major shift in the airline business models, especially of traditional legacy carriers. And, the proactive airlines are moving fast, exemplified by the change in strategies of Singapore Airlines (expanding its brand portfolio) and Qantas Airways, not only setting up a virtual airline operation (with Emirates Airline), but also expanding the operations of its subsidiary, Jetstar Airways.

8. Enlightened governments, for example, in Panama, Colombia, and Peru, are beginning to facilitate the development of aviation facilities, recognizing the huge contribution of the aviation sector to their local economies. The government initiatives may involve the expansion of an airport, coordination among the government, airport and airline policies (as in Panama), or the authorization to allow new entrants (as with VivaColombia).

9. Maturing low cost airlines focused on national markets, having begun to face legacy-like challenges (relative to the workforce, systems, and maturing markets), are expanding into traditional business markets and entering international markets via mergers, codeshares, and indirect networks. Examples of the first include GOL Transportes Aéreos, JetBlue Airways, and Southwest Airlines. An example of the third is WestJet Airlines, intending to fly across the Atlantic from Toronto and Ottawa, in Canada to Dublin, in Ireland with a stop in St. John’s.

10. The availability of the astounding breadth and depth of information has led to significant transparency in passenger fares, leading, in turn, to heightened price competition. Since most airlines have accepted their business to be more or less a commodity business, airlines with lower cost structures have been winning in the marketplace.

11. The emergence of external organizations providing intelligent and trusted search is leading to disintermediation of the airline to its customers, causing airlines to lose interaction with potential passengers. These businesses, armed with the capability to deploy vast quantities of information (especially unstructured data from sources such as social media) and advanced analytics show the potential to become new powerful intermediaries. These new, non-airline entrants have the competency, agility, resources, and connections to offer travel-related services and market personalized itineraries, including the support of 24/7 travel concierges.

12. The relationship between airlines and airports is changing. Some airports, for example, have begun to bid for service from airlines. At the extreme, Ryanair Ltd has a Request For Proposal website via which airports can submit bids for Ryanair to provide a scheduled service.

Figure 1.2 Global middle class in 2009 and prediction for 2030

Source: International Air Transport Association (the OECD, and Standard Chartered Research)

Blurring of Airline Classifications

Before discussing these points, it might be helpful to mention that the distinction between low cost airlines and full service airlines is blurring with the entrance of hybrid airlines. Initially, the low cost airlines had some or all of the following attributes:

• lower fares with simple fare structures;

• no frill service;

• one aircraft type;

• high density and single-class seating;

• point-to-point service in short and medium haul markets;

• no interline services;

• service to secondary airports;

• distribution through an airline’s website;

• high fleet utilization through fast turnaround times;

• no membership with a globally branded alliance.

Then, when some full service airlines began to adopt selected features of low cost airlines and some low cost airlines began to adopt selected features of the full service airlines, the term “hybrid” appeared. For example, while low cost airlines had an excellent capability to distribute their products to price sensitive (non-business) segments in domestic markets with the use of an airline’s website, the distribution process was much too complex to cater to the needs of travelers coming through the corporate departments, through travel agents, and passengers traveling in international markets. Consequently, low cost airlines needed the capability to use multiple channels to distribute their products—their own websites, call centers, mobile apps, and agents (both online and brick-and-mortar) to broaden the reach to attract higher yield passengers such as the corporate segment and to support interline connections. EasyJet Airline, for example, began to use all three of the major Global Distribution Systems (GDSs) to increase the number of corporate travelers (price sensitive but higher yield), a segment now approaching almost 25 percent of its total passengers. Air Berlin is a member of the oneworld alliance and, as such, needs, eventually, to be able to codeshare, interline, and participate in other alliance partners’ loyalty programs. It is also noteworthy that the distinction between the above mentioned categories is also blurring in that a number of full service airlines have also developed their own low cost divisions.

Low cost airlines offer more than one quarter of the seats on a worldwide basis and the number could easily approach one third by the end of 2015. The percentage varies by region and by country. Within Southeast Asia, for example, low cost airlines account for more than one half of the total seats. The variation among countries, with respect to low cost airlines’ penetration, is also significant. The penetration within the Philippines is about one third. However, the Philippines even has two low cost airlines that offer long haul services, Cebu Pacific Air and AirPhil Express.

Based on the aforementioned 12 considerations, airlines are beginning, albeit at different paces, to design market-oriented businesses. For their part, network airlines have already adopted many features of traditional low cost airlines such as the unbundling of the product and à la carte pricing systems. Some are also redesigning their short haul operations. Lufthansa German Airlines, for example, is strengthening and clarifying the role of its Germanwings brand. Aer Lingus not only provides service in short haul markets for other airlines, but also receives short haul service from other airlines for its own operations. Japan Airlines is outsourcing some of its short haul operations to Jetstar while All Nippon Airways is doing the same thing with Peach Aviation. Even China Airlines and Transaero have announced their decision to launch low cost subsidiaries, leading to the availability of low cost service in all ten of the top ten markets in Asia’s Northeast/Southeast region.

The airline industry is also gaining insights from experimentation and iteration around the world. AirAsia and Malaysia Airlines took an equity position in each other and attempted to create a powerful alliance with government approval. The experiment failed. AirAsia also attempted to start a low cost operation in Japan in cooperation with All Nippon Airways. The concept was not readily accepted either by the general public, or by the legacy carriers. However, the experiment did provide valuable insights for future initiatives.

Some traditional low cost airlines are beginning to add features normally associated with full service network airlines, for example, service to conventional airports, multiple fleet types, interline agreements, and distribution through GDSs. JetBlue, for example, has hubs at high cost major airports such as New York Kennedy and Boston Logan, operates two types of airplanes, offers a quasi-two-class cabin, flies to destinations in the Caribbean and South America, has codeshare agreements with about 30 airlines, and offers its products through multiple channels. This convergence in market positioning is leading to the establishment of hybrid airlines, exemplified by the operations of JetBlue, Vueling Airlines, and Virgin Australia that totally rebranded itself. Virgin Australia flies large aircraft such as the Boeing 777 with a three-class configuration featuring a seat selection system, offers in-flight entertainment and in-flight connectivity, has a frequent flyer program, offers airport lounges, and has developed a partnership with major intercontinental players such as Delta Air Lines, Etihad, Singapore Airlines, Tiger Airways, and Virgin Atlantic. Consequently, while the traditional airline classification structure (legacies, low cost airlines, and ultra low cost airlines) is blurring, this book will use it because the transition is not yet complete. Carriers in each classification are adopting the best features from other classifications. For example, à la carte pricing schemes, first implemented by low cost airlines, are now being adopted by legacy carriers. Multiclass configurations used by legacy carriers are now being used by some low cost airlines.

While some airlines have made great strides, there is a tension that exists in that the changes in operations and products (introduced by all sectors of the industry, low cost, full service, and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Rethinking the Airline Business: Where Do We Stand?

- 2 Recalibrating Passenger Value Requirements

- 3 Positioning on the Customization Spectrum

- 4 Progressing to Become Genuine Retailers

- 5 Building Stronger Brands

- 6 Addressing the Role of Loyalty

- 7 Driving the Business Through Technology

- 8 Preparing for Tomorrow

- 9 Attaining Market Leadership: Thought Leadership Pieces

- Index

- About the Author