- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Communications in a Crisis

About this book

The difference between a drama and a crisis is down to good management - or more specifically, good communication. How you communicate with everyone: shareholders, other business partners, employees, the press, and so on, in the hours and days following a potential business crisis is critical. Get it right and the crisis may even strengthen your corporate reputation. Get it wrong and you can imagine the consequences for yourself. Managing Communications in a Crisis details how crisis situations can be identified and dealt with, ensuring the risk to the organisation's financial well-being and reputation is minimised. The book deals with all aspects of communication management in a crisis. Part I considers definitions of a crisis and the theory behind dealing with crisis communications, both externally and internally. Part II explores the practicalities of crisis management communications, the identification of audiences and how each should be dealt with and by whom. The third part of the book contains valuable checklists and succinct supporting information for the key aspects and roles of the communication process. The combination of these three approaches will help you to develop your own crisis strategy, tailor-made for your organization. The text is supported by a wide range of case histories. Some of these you will recognise and others, perhaps through good management, never entered your radar. The authors are highly experienced advisors to companies of all sizes in the demands of crisis management communications. Their company, The Aziz Corporation, is the UK's leading executive communications consultancy, specialising in presentation skills, media handling and crisis management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing Communications in a Crisis by Peter Ruff,Khalid Aziz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Understanding Crises and the Theory of Communication

1 Understanding crises

There are almost as many definitions as crises themselves but the one which sums it up for us is the following:

A crisis is any incident or situation, whether real, rumoured or alleged, that can focus negative attention on a company or organization internally, in the media or before key audiences.

In the case of a company that offers shares to the public this means ‘anything that could potentially have an impact on the share price’. For other organizations it means ‘anything that could actually, or potentially, damage our reputation’.

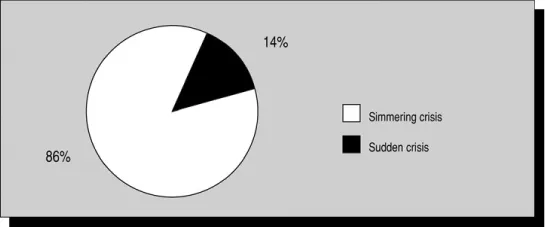

The use of the word ‘potentially’ is important here. By far the most satisfying part of our work is helping spot the potential problem or problems and dealing with them before they become a full-blown crisis. The precise nature of an emergency situation might be hard to anticipate but work done in the United States during the 1990s showed that, of all crisis events reported in the media, there were two clear categories: events that were ‘simmering’ and those that were ‘sudden’.

‘Sudden’ events encompass accidents and emergencies, acts of terrorism, mechanical breakdowns, a hostile take-over or some unexpected legal action.

‘Simmering’ events cover situations that lurk beneath the organization’s surface and can erupt into a crisis at any time. Industrial unrest, criminal actions of varying types and inefficient management would all fall into this category.

An interesting element of companies’ and organizations’ perspective in crisis management is their general assumption that a crisis will be sudden and unexpected whereas, in reality, it is much more likely to be predictable and expected.

We are retained as crisis management consultants for one of the UK’s largest providers of service management for office and residential properties. They operate all over the UK, employ thousands of people and often face emotionally charged situations which, if details reached the media, could have a damaging effect on their share price. For example, a security guard may have allowed robbers into the premises by ignoring procedures, the maintenance of an office central heating system has been inefficient and has led to persistent breakdowns or a waste contractor has been badly chosen and there are complaints from the businesses within the building. On one grizzly occasion, a warden supplied by the company to provide holiday relief at a residential home for the elderly failed to notice that a man had not been seen for a while. It turned out to be ten days, and all that time he had been lying dead from a heart attack in his so-called ‘protected’ flat.

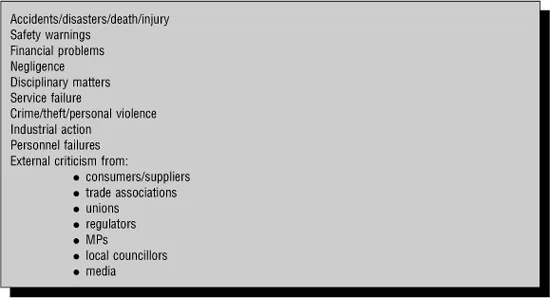

When, as a direct result of a crisis review, the company called us in to provide advice we asked to see their existing plan. At the front of a very smart manual was a page listing the priorities for crisis management within the company and from where they could expect external criticism if they got it wrong (see Figure 1.1). The interesting thing about that page is that they had the ‘sudden’ crises at the top of their list of concerns followed by the ‘simmering’. Were they correct to do so? We think not.

Figure 1.1 Major UK service

company list of priorities for crisis management

company list of priorities for crisis management

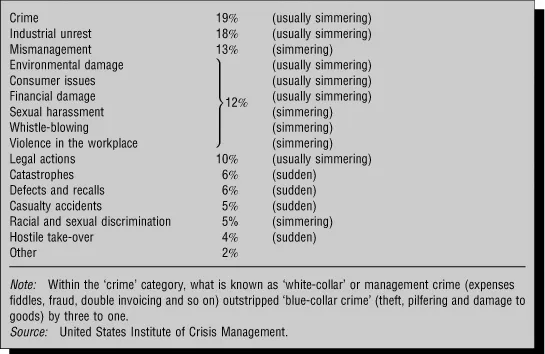

There is very little accurate data in Britain but, in the United States, the Institute of Crisis Management reviewed thousands of events serious enough to be reported in the media. In all, they looked at 55 000 separate items in 1500 publications between 1990 and 1998. The findings (see Figure 1.2) show quite clearly that 86 per cent of them could be described as ‘simmering’ and only 14 per cent ‘sudden’. For more detailed analysis, they took all the events from one year – 1997 – and broke them down according to the nature of each crisis (see Figure 1.3). This exercise showed that the majority of the events were ‘simmering’ and therefore preventable. If you take the top three types of crisis -crime (19 per cent), industrial unrest (18 per cent) and mismanagement (13 per cent) – they add up to half the total of all reported crisis situations and could have been detected and prevented if only there had been such a process in place.

Figure 1.2 Crisis news events, United States 1990-98

Source: United States Institute of Crisis Management.

The American business environment may be somewhat different from that in other parts of the world, but we believe that a similar pattern would emerge anywhere. A shrewd crisis management team should be constantly vigilant for ‘simmering’ issues and have a mechanism in place to prevent them from exploding in the public domain. The evidence in the United States suggests that they should be particularly on the look-out for industrial unrest, mismanagement and ‘white-collar’ crime!

On the basis that it is possible to counter the vast majority of situations, what about those that we define as ‘sudden’? An academic who has studied crisis management over many years, Otto Lerbinger, has identified seven definable types of sudden emergencies. In his book The Crisis Manager: Facing Risk and Responsibility (1997) he describes them as follows:

• Natural disasters: fires, explosions and bad weather.

• Technical disasters: spillages and faulty equipment.

• Crises of confrontation: industrial disputes or the development of opposition by single-issue external groups.

• Acts of malevolence: terrorism, sabotage and kidnapping.

• Misplaced management values: strategic investment errors and ignoring investors’ concerns.

• Acts ofdeception: fraud, expenses scams and false invoicing.

• Management misconduct: harassment, bribery and corruption.

Figure 1.3 Sudden versus simmering crises, United States 1997

This book is designed to help crisis teams deal with the events that come under these seven categories while recognizing that they are comparatively rare events. We also want to help you identify the more common ‘simmering’ events and demonstrate how they can be dealt with.

KEY LEARNING POINTS

REFERENCE

Lerbinger, Otto (1997), The Crisis Manager: Facing Risk and Responsibility, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

2 Elements of crisis management

For both crises that can be spotted in advance and the lesser category that comes out of the blue, there are four stages or elements involved in their management. Your planning must allow for each of these, because only if you deal with each of them successfully will your crisis plan truly work. They cover preparation, notification, communications and recovery. Each will have its own timeline which may cover hours, through days, weeks, months or even years.

THE FOUR ELEMENTS

EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS

This element is heavily dependent on your business sector and how it is regulated. A sole trader is not expected to prepare for an emergency except by using common sense as a human being. A small business employing a handful of people is expected to take precautions under health and safety and employee regulations. If it is a business dealing in, say, food then other legislation applies. A major manufacturer has to comply with a whole array of health, safety and environmental programmes and must employ teams of people to make sure that they are complied with. A company dealing with potentially dangerous substances such as chemical or nuclear products comes under even tighter regulation that will be enforced by government agencies. Running in parallel with all this, there are often requirements laid down within companies to make sure that their emergency planning is uniform throughout their operations. This is particularly true of corporations with many subsidiaries and a worldwide presence. It is not uncommon for each operating division to have its own plan, but this will have to dovetail with those of the corporate headquarters. Well-run organizations update and practise their emergency preparedness plans at regular intervals.

We will go into more detail in later chapters, but preparedness has to include every aspect of the business you are in. How will an emergency affect personnel, legal, finance, operations, sales, marketing, health and safety, transport and communications?

EMERGENCY NOTIFICATION

If something bad happens, who should be told and how? The notification process is usually divided into what you are obliged to do under the law and legislation and what you should do for the good of your business. Legal obligations are notified by the body responsible for policing the issue and held by the manager tasked with dealing with them. In-house procedures are usually held by the same person but will address corporate standards set by the company itself. They are usually stricter than those laid down by local or national statutes.

The main point is that the company must be aware of both its in-house and external obligations.

Let us take an example of what we mean at the ‘high’ end of the potential emergency scale. Industries that deal with potentially hazardous materials have statutory obligations under a raft of legislation designed to protect the public. Much of it is covered by UK health, safety and environmental laws but, in recent years, that has extended to European and international regulation as well. Some notification in this category will need to be instant – anyone dealing with nuclear materials, for example, must tell the Nuclear Installations Inspectorate at once. As the emergency unfolds and inquiries are initiated into the cause, other obligations come into play. There will almost certainly be formal procedures for notification within the company. Most crisis plans require the highest officers of the company (that is, those with legal obligations for the welfare of the company, such as board members) to be informed and updated at regular intervals.

It is important to remember that these are formal requirements under company laws and they should not be confused with our next section which covers internal and external crisis communications.

Less formal, but no less important, are notifications that should be made to outside bodies (for example, trade associations) with an interest in your sector. In addition, some contracts with customers and suppliers have clauses that require you to notify them of an emergency that could affect their relationship with you.

One of the best-known notification procedures has been codified by the aviation industry. If the pilots or engineers of an airline encounter something that could endanger air safety they have an obligation to issue a ‘bulletin’ alerting others. When Concorde crashed in Paris, the operator, Air France, worked closely with their main competitors, British Airways, to identify the cause of the crash, the subsequent explosion and what needed to be reinforced on the aircraft to make it safe to fly again.

Similar arrangements apply to other sectors on the basis that everyone can learn lessons from an emergency. It is also regarded as an important element in the positive public perception of the business.

CRISIS COMMUNICATIONS

This is allied to the section above but involves different disciplines. It involves the ‘targeting’ in advance of all internal and external audiences and analysing what they will need, and want, to know. It also involves calculating what you want them to know under given circumstances. Many a routine incident or event has been turned into a crisis because too many people were told too much and the situation became exaggerated and out of control.

Control over information is crucial in an emergency but so, too, is the need to give people the power to cascade what information is necessary with speed and efficiency. How often have you read a piece in the newspaper about your company or organization only to realize that you should have been told about it in advance? Media reports are very often the means by which employees find out that their senior manager has walked out or been fired thus throwing the company into chaos.

Of course, security of information is critically important particularly since the advent of instant IT and telecom systems. Part of the preparation for dealing with an emergency is to decide in advance whether you will need secure channels for some information and not others. Remember the civil servant who sent a quick e-mail to her colleagues minutes after the attack on the World Trade Centre in New York? Now, she advised, would be a good moment to get out and ‘bury’ any negative departmental news. This communication was too ‘juicy’ to stay secure because it neatly summed up an attitude that was beginning to worry commentators and the public about the government’s efforts to manage the news. Consequently, the existence of the e-mail itself became an emergency.

The above example was an internal document that became public unintentionally. In a crisis or emergency it is often a good idea to have draft documents for external audiences prepared in advance so that they only need refining to reflect what has happened. The phrasing of each draft should be worded so as to acknowledge the likely needs of the audience. A draft news release is likely to be substantially different in tone from a letter ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures, examples and case studies

- About the authors

- Introduction

- Part I Understanding Crises and the Theory of Communication

- Part II Practical Crisis Communication

- Part III Appendices

- Index