eBook - ePub

The Maya Forest Garden

Eight Millennia of Sustainable Cultivation of the Tropical Woodlands

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Maya Forest Garden

Eight Millennia of Sustainable Cultivation of the Tropical Woodlands

About this book

The conventional wisdom says that the devolution of Classic Maya civilization occurred because its population grew too large and dense to be supported by primitive neotropical farming methods, resulting in debilitating famines and internecine struggles. Using research on contemporary Maya farming techniques and important new archaeological research, Ford and Nigh refute this Malthusian explanation of events in ancient Central America and posit a radical alternative theory. The authors-show that ancient Maya farmers developed ingenious, sustainable woodland techniques to cultivate numerous food plants (including the staple maize);-examine both contemporary tropical farming techniques and the archaeological record (particularly regarding climate) to reach their conclusions;-make the argument that these ancient techniques, still in use today, can support significant populations over long periods of time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Maya Forest Garden by Anabel Ford,Ronald Nigh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Context of the Maya Forest

The conventional story of the magnificent Maya civilization ends with the disappearance of the Maya people and destruction of their environment in Belize, Guatemala, and Mexico. This myth persists despite historical accounts that disprove it. Cortés, on his march to Lake Petén Itzá, describes the area as populated, feeding and housing his army of more than 3,000. Moreover, the continuous 30-century period of population development of the ancient Maya Lowlands—from the Preclassic to the Terminal Classic period, through the Colonial period and into present times—represents long-lasting continuity. The source of Maya wealth lay in their landscape and in their profound understanding of how to use it. In fact, the Maya’s subtle patterns are embedded within the forest structure. The historical ecology of this forest is complex (cf. Balée 2006); to understand it means examining contemporary agroecology of traditional farming and the paleoenvironmental record of the Late Classic Maya. An overview of the Maya timeline and the chronology of the environmental record reveal the discrepancy between the growth and sophistication of the Classic period Maya and the imagined environmental destruction. While most studies of the Maya assume that the collapse of the civilization was related to deforestation, such as that caused by humans, today the Maya forest is known for its remarkable diversity and its abundance of useful plants.

Introduction

The Lowland Maya region (Figure 0.1) was transformed by humans from the initial peopling of the New World. They influenced the landscape ecology from the outset, managing and domesticating plants in a setting that changed from an arid temperate zone to a wet tropical one around 10,000 to 8,000 years ago (Table 1.1). When early Maya settlements emerged, from 4,000 to 3,000 years ago, the community increasingly depended on horticulture and the expansion of agriculture while essentially living within the forest. The archaeological evidence from the Preclassic Maya focuses first on areas with secure water reserves, as noted by Dennis Puleston and Olga Puleston (1971). As populations grew, farming settlements went on to occupy virtually every locale with the potential for cultivation. At this time the Maya built major centers as impressive as anything from the Classic period, including Mirador and Nakbe, in the Guatemalan Petén, and Cerros and Cuello, in Northern Belize. Based on a survey around Tikal, Lake Yaxha, and the El Pilar area east of Tikal (Ford 1986, 1990; Puleston 1973; Rice 1976), by 2,800 years ago, in the Middle Preclassic, Maya farmers largely occupied the desirable, well-drained uplands of the region—the same zones that were most densely occupied centuries later during the Late Classic.

Between 2,000 and 1,000 years ago Maya centers and settlements grew and expanded over the landscape during the Classic. Much has been made of the so-called Terminal Classic collapse, a turbulent time when the culture of sacred monarchs underwent a major transformation and important centers in the southern area gradually ceased to be maintained (Webster 2002). The idea of collapse, however, exaggerates the reality and promotes a picture of population crash without evidence. Dramatic “collapses,” or the gradual abandonment of impressive urban centers, appear to be a signature of Maya culture from the Preclassic and signals transformations of settlement patterns (Aimers and Iannone 2014; Iannone 2014; Chase and Scarborough 2014a). Nevertheless, the Maya persisted and significant numbers still lived around Postclassic centers when the first Spanish conquistadors arrived several centuries later (Alexander 2006).

Hernán Cortés’s Fifth Letter to the emperor and king of Spain, Charles V, provides a unique glimpse of the Prehispanic Maya (Cortés 1985[1526]). In this letter of September 3, 1526 (1985:355–449), Cortés describes his epic entrada to the very heart of the southern lowlands at Lake Petén Itzá, some 70 km from the abandoned Classic city of Tikal. The “heavily settled region” (Jones 1998:31) that the Spaniards crossed was already feeling the first effects of the European invasion provoked by the dramatic demise of the Aztec civilization. Cortés’s party traversed Tabasco, Acalan, and Central Petén, where they encountered many large towns, often spaced less than a day’s journey apart but separated by “dense forests,” groves, and fields (Cortés 1985:363–386). Cortés’s large army struggled to move overland in a region of Maya waterways and footpaths. Even with local maps, the Spanish spent many days lost among forests and bogged down in the swamps, often deliberately misled by terrified local guides, as Cortés admits in his letter (e.g., Cortés 1985:377). Cortés and his retinue were, nevertheless, nearly always well billeted and provisioned—willingly or not—by the Maya themselves (Jones 1998:32–33).

TABLE 1.1. Occupation Chronology: Eight Thousand Years in the Maya Forest

| Years Before Present | Human Ecology | Land Use | Cultural Period |

| 8000–4000 | Hunting & gathering | Mobile horticulture | Archaic |

| 4000–3000 | Early settlement | Settled horticultural forest gardens | Formative Preclassic |

| 3000–2000 | Emergent Preclassic centers | Settled forest gardens | Middle-Late Preclassic |

| 2000–1400 | Civic center expansion | Expanding milpa forest gardens | Late Preclassic-Early Classic |

| 1400–1100 | Center and settlement growth | Centralized milpa forest gardens | Late Classic |

| 1100–800 | Civic center demise | Community milpa forest gardens | Terminal Classic-Postclassic |

| 800–500 | Settlement refocus | Dispersed milpa forest gardens | Late Postclassic |

| 500-Present | Conquest depopulation | Disrupted milpa forest gardens | Colonial, National, Global |

Though the Maya inhabitants fled before him, it is remarkable that Cortés found enough food left behind in well-ordered towns to maintain his huge entourage of 3,000 Mexican warriors and almost 100 Spanish horsemen. During a journey through a largely hostile territory with only walking trails, in what is generally considered a military disaster, Cortés mentions having to sleep in the open air just 17 or so nights over the more than 150 days it took to travel from Coatzacoalcos to Tayasal/Nohpeten, the Itzá capital (Cortés 1985:360–386). The rest of the time he and his vast army were comfortably housed and fed, if reluctantly, in Maya towns. Only between Tabasco and Acalan, what is now South-Central Campeche, in the Kejach territory near Calakmul of the greater Petén, did Cortés have to spend several nights in what he calls a “depopulated” area before finding a Maya settlement large enough to house his horde. A careful reading of Cortés’s description and Jones’s overview suggests that in the southern Yucatan Peninsula the Maya dwelt prosperously on the forest landscape in the early sixteenth century. This conjecture is underscored more than a century later, when Ursua, during his 1697 conquest, pleaded for support (Schwartz 1990:54–55) and detailed a list of the foods that he and his men were “forced” to eat, including chicozapote, macal, nance, and other foods found in the forest gardens. It was a veritable cornucopia, but the Spanish had culturally defined standards and found these foods inedible (Terán and Rasmussen 2008:134). Yet what allowed the Maya to succeed in their tropical ecosystem and produce the food they ate was what the Spanish called the milpa. The milpa is crucial to the resource-management system that shaped the Maya forest to meet subsistence and tribute needs, develop the political economy, and promote local and long-distance trade.

The Maya Lowland Environment: A Comprehensive Production Platform

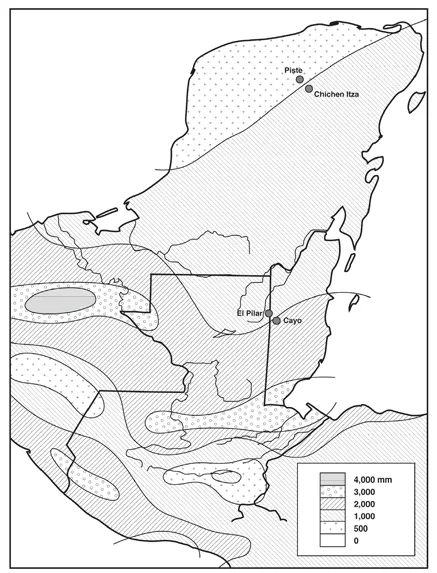

The fundamental geographical feature of the Maya forest at the regional scale is the environmental gradient from the high cloud forests of the mountains of Chiapas and Guatemala in the south, around 15 degrees north latitude, through mountain ranges and ridges that gradually descend into the lowland limestone plain of the Yucatan Peninsula, around 21 degrees north. Average annual rainfall varies here (Figure 1.1) from less than 500 mm in the northwest Yucatan Peninsula to 4,000 mm in the far south (White and Hood 2004; West 1964). Commonly divided into the wet and dry season, local farmers see the rainy “winter” season as, first, the warm wet period associated with hurricanes, and then a cool wet period associated with the nortes, followed by the dry “summer.” Along the environmental gradient, forests grow up over an essentially limestone base, though there are variations depending on local climate, water, and soil conditions (Chase et al. 2014; Dunning et al. 1998; Dunning et al. 2009; Liendo et al 2014).

FIGURE 1.1. Annual rainfall distribution in the Maya area. ©MesoAmerican Research Center, UCSB

The capricious limestone bedrock creates unpredictable access to water: Water rarely flows on the surface (Chase and Scarborough 2014a, 2014b; Fedick 2014; Iannone 2014; Lucero et al. 2014). Instead it is absorbed through fissures into the bedrock or flows in underground streams within the limestone. Two major river systems and several smaller ones flank the east and west sides of the central lowlands: the Belize/New River on the east and the Usumadnta/Candelaria on the west. When openings in the limestone drop below the water level, lakes, lagoons, or, as in northern Yucatan, cenotes may form. In the wet season water collects within closed lowland depressions throughout the region. It is estimated that at least 40 percent of the region is wetlands (Dunning et al. 2002; see also Fedick and Ford 1990). This is consistent with data from El Pilar, 47 km to the east of Tikal, where poor drainage characterizes 38 percent of the area (Ford et al. 2009). These variations of karstic topography and water access generate the following four basic ecosystems (Figure 1.2) in the central Maya Lowlands (Fedick and Ford 1990), ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Prosperity across Centuries

- Chapter 1 The Context of the Maya Forest

- Chapter 2 Dwelling in the Maya Forest: The High-Performance Milpa

- Chapter 3 Environmental Change and the Historical Ecology of the Maya Forest

- Chapter 4 Maya Land Use, the Milpa, and Population in the Late Classic Period

- Chapter 5 The Forested Landscape of the Maya

- Chapter 6 Maya Restoration Agriculture as Conservation for the Twenty-first Century

- Appendix A Basket of Mesoamerican Cultivated Plants

- Appendix B Favored Trees

- Notes

- References

- Index