![]()

CHAPTER 1

An Introduction to Museums and Public Value

CAROL A. SCOTT

Abstract

We are living in times of accelerated economic, cultural, political and technological change.

Leaders of publically-funded museums simultaneously navigate the shoals of change on multiple fronts – addressing emerging social issues, responding to adjustments in government policy and adapting to new funding thresholds. Working with change, while maintaining institutional value and building a sustainable future for the institution is the work of today’s museum leader.

Within this context, Mark Moore’s vision for public management continues to resonate. He recognizes that leaders of public institutions operate within a dynamic environment. Instead of perceiving constant change as overwhelming, Moore envisages public managers as proactive stewards of public assets that can be directed purposefully to making ‘a positive difference in the lives of individuals and communities’ (Moore and Moore 2005, 17), and as leaders with influence to help governments ‘discover what could be done with the assets entrusted to their offices, as well as ensuring responsive services to users and citizens’ (Moore and Benington 2011, 3).

This vision is important at a time when a global economic crisis is affecting the amount of public funding available and notions of what kind of social return is expected on public investment. In Chapter 9, ‘Museums and Public Value: A US Cultural Agency Example’, Marsha Semmel refers to the ‘shifting ecologies’ of the funding landscape in that country. Shifts in the funding landscape are creating corresponding shifts in traditional notions of ‘public good’, in ideas of what constitutes ‘essential’ public benefits and to perceptions about which agencies deliver benefits worthy of funding support. In this climate, being able to demonstrate that museums create public value is ceasing to be an option.

Public value as a theory and model of management offers guidance, structure and purpose in these challenging times. It focuses us on the benefits that museums can create in the public sphere. It directs us to use scarce resources for maximum benefit. It offers an approach to building relationships with communities and governments that are long-lasting and sustainable.

It is now 17 years since Mark Moore published Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government (1995) but as a theory, model and practice it continues to be discussed, debated, received and adopted.

This introduction explores Moore’s model and its place within a wider discourse on value in the cultural sector. It takes the pulse of public value today and examines the implications of adopting a public value approach for professional practice in museums.

Introduction

WHAT IS VALUE?

‘Value’ can refer to the moral principles of individuals and the ethical ideas that guide collective action such as beliefs in the principles of democracy and tolerance. ‘Value’ is associated with worth, importance, significance and usefulness. Outcomes of programmes and services that are ‘valued’ are those which have a beneficial impact for an end-user (Poll and Payne 2006).

WHAT IS PUBLIC VALUE?

Public value refers to planned outcomes which add benefit to the public sphere. Benington (in Moore and Benington 2011, 43) describes the public sphere as that ‘web of values, places, organizations, rules, knowledge, and other cultural resources held in common by people through their everyday commitments and behaviours, and held in trust by government and public institutions’.

The focus on the public sphere situates public value in relation to decisions which are made in the general public interest. Benington (in Moore and Benington 2011, 45–6) argues that public value addresses ‘unmet social needs’. Moore (2007) is more discursive, suggesting that public value can tackle social conditions which need to be ameliorated, substantive problems to be solved, rights to be vindicated and opportunities to be exploited.

HOW DO WE CREATE PUBLIC VALUE?

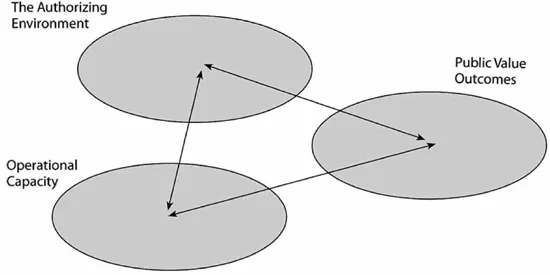

Moore (1995) developed his theory and model with governments and the publically-funded sector in mind. He envisaged governments and institutions working together with the shared purpose of creating value that would benefit the general public. Moore mapped this relationship through a ‘strategic triangle’, a framework for aligning three distinct, but interdependent, components (Moore 1995, 31).

The points of the triangle identify (a) the authorizing environment which provides legitimacy and support through approvals and funding, together with (b) the operational environment which applies its organizational capacity and assets to (c) the joint purpose of creating public value (see Figure 1.1).

The authorizing environment comprises those who have the power to grant or withdraw approval or place conditions on the allocation of resources. It includes policymakers and legislators, bureaucrats and funders. In government, because many of these authorizers are elected ‘representatives’ who are tasked with making decisions on behalf of their constituents, the authorizing environment also includes all the individuals and interest groups who have a stake in decisions and who can influence those who are in representative positions (Moore and Moore 2005, 37). This supplementary stakeholder cohort is extensive and can include arts practitioners, representatives of arts and cultural heritage organizations, special interest groups, professional associations, other government departments, private agencies and the media.

Figure 1.1 Public value strategic triangle

Source: Moore, M. and Benington, J. (eds) 2011. Public Value: Theory and Practice, 31, reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan.

The operational environment refers to the assets and capacity of publically-funded organizations. These assets include the Acts under which organizations are established, missions and purpose, history in pursuit of that purpose, leadership (Boards, CEOs and management teams), human resources, available funds, collections and the depth, breadth and efficacy of strategic partnerships. Public value focuses management on what one does with the organization’s assets. It offers ‘a renewed emphasis on the important role public managers can play in maintaining an organisation’s legitimacy in the eyes of the public’ (Blaug et al. 2006, 6) to achieve ‘its politically mandated mission – roughly stated, to make a positive difference in the individual and collective lives of citizens’ (Moore and Moore 2005, 17).

From the perspective of policy-makers and funders, public value is a way of framing and accounting for governments’ social return on investment (ABS 2008, 10) and effectively targeting that investment in a time of rising demand within imitated budgets for public spending. For museum leaders, it acknowledges the reality of the complex and changing environment in which operations occur and the multiple stakeholders with whom they must engage and to whom they owe accountability. It provides a focus and direction for ‘harnessing and mobilizing the operational resources … both inside and outside the organization, which are necessary to achieve the desired public value outcomes’ (Moore and Benington 2011, 4).

For Holden (2004), Moore’s approach offered the possibility of a ‘new accord’ in which governments and public institutions would work in a spirit of collaboration and consensus, combining approval processes, funding and organizational assets to create value in the public sphere. This was ‘new’ in relation to the structure of public administration that was in place when Creating Public Value was first published and is best understood within the context of that history.

Background

The model of public administration in place when Moore published in 1995 was called the New Public Management (NPM). It was part of a modernizing1 agenda implemented by governments in OECD2 countries from the late 1970s in response to both another world economic crisis in the early years of that decade, and the growing awareness that funding post-World War II welfare states to the degree current at the time was unsustainable.

Sweeping reforms were introduced to divest governments of the direct costs of what had previously been publically-provided services. Diversification and outsourcing of delivery were introduced. At the same time, cost savings were sought in a reduced public service which now had to be more efficient in its management of public funds and more accountable for their use. Governments looked to the private sector for models, adopting and adapting many features of commercial performance. Management by results, performance evaluation and budgetary control were introduced to monitor and regulate the public sector. Control was a major feature of the New Public Management. It was characterized by a top-down, regulatory environment which, though it initially focused on economic reform, eventually extended its remit to include social policy.

Under this regime, the ‘arm’s length’ principle was diminished and funding for public institutions was more closely tied to delivering government policy. Policy was pragmatic, ‘instrumental’ and unashamedly interventionist. Its effectiveness was assessed through ‘evidence-based policy’ which formalized the need for performance data to provide proof of achievement against targets set by government.

THE NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT, MUSEUMS AND VALUE

The responses to the New Public Management from the museum sector can best be summarized as a combination of compliance, criticism and challenge. Though the regulatory environment required compliance as a condition of funding, the museum sector was not quiescent. It criticized governments for adopting a system originating in the profit-making, commercial world which measured success by a financial bottom line. It argued that the multi-dimensional briefs and wide range of stakeholders in the public sector make meaningful performance assessment a much more complex issue (Ames 1991; Bud et al. 1991; Walden 1991). The ‘narrowness’ of the instrumental agenda came under attack, with critics pointing out that it obscured other, equally important, outcomes which were not captured in systems of measurement favouring quantitative data at the expense of qualitative information.

An increasingly vociferous body of criticism argued for a more holistic view of the value produced by culture and more appropriate measurement systems to assess it. The result was a lively conversation about cultural value – what value, whose values and how that value should be measured. Holden (2004, 10) issued a call for an approach:

capable of reflecting, recognising and capturing the full range of values expressed through culture, make explicit the range of values addressed in the funding process to encompass a much broader range of cultural, non-monetised values, view the whole cultural system and all its subsystems, and understand how systemic health and resilience are maintained, recognise that professional judgement must extend beyond evidence-based decision-making, see the source of legitimacy for public funding as being the public itself, overturn the concept of centrally driven, top-down delivery and replace it with systemic, grass roots value creation.

WHAT VALUE?

Within this discourse, instrumentalism became associated with government policies that sought to achieve specific economic and social outcomes, ‘going beyond function and having aspirations to contribute to a wider agenda of social change’ (Davies 2008, 260). Though O’Neill (2008, 293) reminds us that the application of museum purposes and functions to wider social issues is not a new phenomenon, the concept of instrumentalism within the last decade of the twentieth century and the early part of this century became associated with increased demands for accountability and with funding allocations linked to delivering government policy.

Belfiore and Bennett (2006, 2), however, argue that the very predominance of the instrumental agenda and the vigour with which it was driven by governments created a tension which ultimately served a useful purpose; it focused the cultural sector on articulating its value, something which had been less necessary under traditional notions of funding culture as a ‘public good’. In the search for a more holistic and nuanced paradigm, other value dimensions came to the fore. Initially, the debates coalesced around instrumentalism’s opposite – intrinsic value.

‘Intrinsic’ describes ‘the set of values that relate to the subjective experience of culture intellectually, emotionally and spiritually’ (Holden 2006, 14). Intrinsic value was given prominence in publications by Holden (2004) and McCarthy et al. (2004) both of whom developed cultural value paradigms which included instrumental and intrinsic dimensions.

Holden’s paradigm, however, included a third dimension which he termed ‘institutional’ value and which he described as ‘the processes and techniques that organisations adopt in how they work to create value for the public … enhancing the public realm … as discussed in the work of Mark Moore’ (Holden 2006, 17).

For Holden, one of the attractions of Moore’s concept of public value was its vision of a relationship between governments and publically-funded institutions where the conflicts and contest which had characterized the New Public Management could be replaced with a more consensual approach to decision-making and where funders, policy-makers and cultural leaders could collaborate in decisions about what public value should be delivered and how it could be measured.

Public Value and Museums

Nearly two decades after it was first published, the theory of public value still resonates in terms of its outward-looking focus, its conceptual mapping of relationships with governments, stakeholders and the public and its emphasis on directing activity to creating benefit in the public sphere.

Moore (1995) aimed for a system of ‘practical reasoning’ (Horner and Hutton 2011, 122) which would guide managers to use state-owned assets to achieve public good. What constitutes that system of ‘practical reasoning’, the processes, procedures and issues involved and the issues that it raises for museums is explored in the following chapters which are organized under three general headings:

1. The operational environment: public value building blocks

• management: frameworks and processes

• intentional planning

• evaluation

2. Case studies: implementing public value

• planning for social impact

• co-production with the public: education and learning

• co-production with the public: exhibitions

3. Working with the authorizing environment

• measuring public value

• the United States: a federal agency and public value

• the UK: public value at national government level

• the UK: a professional association perspective

• the UK: a partnership in Scotland.

THE OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT: PUBLIC VALUE BUILDING BLOCKS

One of the first things required for a museum CEO considering whether to adopt a public value approach, is reassurance that theory and practice are congruent with current models of strategic management and standards of best practice.

Mark L. Weinberg and Kate Leeman address this topic in the next chapter. They begin by assessing pub...