- 576 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Fraud: The Counter Fraud Practitioner's Handbook looks at fraud investigation methods and explores the practical options for preventing and remedying fraud. An effective fraud and financial crime strategy involves intelligence and prevention, criminal and civil legal procedures, and asset recovery, all of which may involve investigators, internal auditors, security managers, in-house and external legal counsel and advisors. Your strategy depends on the outcomes you are seeking, the nature of the fraud or crime committed and the countries involved. Fraud provides a clear picture of the role of compliance, civil and criminal legal process in any fraud strategy. Chapters then cover investigation strategies for each of the following types of fraud: benefit, health, procurement, employee, telecoms, fiscal, corporate, charity, legal and accounting. Part Three explores the practical options for fraud prevention and remediation, including both civil and criminal asset recovery. This is an essential reference for both public and private sector fraud and security specialists who need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each element of their organization's strategy against fraud and are seeking to learn from the approach of their colleagues in other industries or organizations. Written by and for practitioners, it is a handbook that deals with the knowledge, detail and the craft that underpins all effective anti-fraud work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fraud by Alan Doig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I: Themes, Trends and Perspectives

CHAPTER 1

Trends and Costs of Fraud

Introduction

Fraud is a deceptively simple word covering a very broad territory. It is a way of making money illegally via deception, whether that deception is directly person-to-person in real space or in virtual space; operates by false stories alone or via the use of deceptive real or e-documents or via Personal Identification Numbers; or uses genuine or phoney businesses as tools of fraud. Thus there is a huge range of contexts in which frauds, large and small, lasting milliseconds (like unauthorised electronic funds transfers) or many years (like the Madoff ‘Ponzi’ scheme),2 are perpetrated. Some are planned as scams from the start, sometimes as part of an ‘organised crime group’ activity; others–with or without involvement of outsiders–are the result of insiders spotting system weaknesses which, if undetected, may spread from there into much larger schemes. After the event, it can be a matter of interpretation into which planning category any given fraud falls. But the level of harm may be independent of that level of planning, and many losses may have been generated by business activities rather than pure criminal profit: hence, in addition to clever laundering, the fact that such modest amounts are sometimes recovered from corporate losses.

Concern about fraud has been growing in governmental, policing and in some business circles, because it is regarded as the modern crime, and one to which managers, employees and ‘organised crime’–a rather vague construct–aspire if they had sufficient confidence and skills to get into ‘it’. Frauds offer higher rewards and lesser risks of long jail time than do conventional crimes, posing the question of why would people do theft, burglary and robbery (or even drugs trafficking) if they could do fraud? On the other hand, mainstream criminal justice resources have not kept pace with these concerns, and governments have tried ‘market solutions’, partly to keep responsibility for fraud prevention at the business and government levels which generate the risks, and partly because they are unwilling to transfer existing resources to fraud-fighting, or sometimes to share resources in cross-sectoral fraud prevention (Doig, 2006; Doig and Levi, 2009). In this chapter, we will not discuss controls specifically but will focus upon the cost and scale of fraud, bearing in mind that fraud–like all crimes–is the result of the interaction between motivated offenders, their skill sets, and the opportunities presented by victims and by those entrusted with controlling risks.

What is Fraud?

In England and Wales, ‘fraud’ was redefined in the Fraud Act 2006, which created a new general offence of fraud and introduced three possible ways of committing it–by false representation (s.2), failure to disclose information when there is a legal duty to do so (s.3 e.g. by a solicitor to a client), and abuse of position (s.4): see http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/d_to_g/fraud_act/. The term covers a huge range of both acts and criminal actors, from (a) group-organised frauds e.g. ‘carousel’ VAT, ‘boiler room’ share manipulation, insider dealing rings, mortgage fraud rings and payment card counterfeiting; through (b) investment ‘Ponzi’ Schemes, usually committed by several people; to (c) embezzlement and other frauds by individuals that may be sufficiently well organised to obtain funds, but are not usually considered to meet the criteria for ‘organised crime’. How does this overlap with other categories of ‘serious and organised crime’? Fraud is one area where–depending on logistics related to the form of the crime–well-organised offenders can profit extensively from crime without needing to form larger groups and networks.

Trends in Fraud

The dimensions of fraud are difficult to determine. Normally, we would look to statistical data on crime and/or cost of crime trends to enable us to judge whether a problem is getting better or worse. However despite attempts to improve fraud statistics, these cannot readily be applied retrospectively to past data, which are really too patchy and unreliable to be confident that the problem is growing in the way that most people think it is. This is compounded by media tendencies to look unhelpfully at ‘fraud’ as if it were one homogeneous problem, and to swallow ever-larger figures presented under the banner of ‘awareness raising’. Despite very large error margins in estimation, what we do know is that fraud is a very large sum, and it is larger than other forms of property crime. However although some fraudulent trading, mortgage frauds, etc., stimulated and were revealed by the global financial crisis, losses from fraud were almost certainly less than those from bad lending decisions.

The National Fraud Authority (2010) estimated UK fraud losses at about £30 billion in 2009: around £621 a year for every man, woman and child in the UK (though given the uneven distribution of losses, such average figures are forensically valueless). The following year, this figure had risen to £38.4 billion and in March 2012 the total was £73 billion (National Fraud Authority, 2011 and 2012). But these cover a variety of sorts of victim and variations in in amounts involved. Card fraud losses in 2012 totalled £341 million, nearly half the losses in 2008 (and a record low in the past decade as a ratio to turnover); online banking fraud losses £35 m., a significant fall from the previous three years, especially taking into account the rise in people banking online; and cheque fraud losses fell substantially by a third since 2008 to £28.9 m. (Financial Fraud Action UK, 2012), although they rose slightly in the 2012 Annual Fraud Indicator (NFA, 2012: 46). 54 per cent of businesses have been a victim of fraud or online crime in the last twelve months (Federation of Small Businesses). In 2008, four per cent of all insurance claims by value (excluding life insurance) were deemed fraudulent, against three per cent in 2007 (ABI); and an average of 100 new victims of ‘boiler room’ share sale frauds contact the police each week. These victims report losses ranging from £3,000 per person up to more than £1 million (http://www.attorneygeneral.gov.uk/nfa/WhatWeDo/FraudFacts/Pages/TheCostofFraudtousall.aspx). The public sector accounts for 55% of the total figure, the private sector 31% and fraud against individuals 14% (NFA, 2011).

Currently, time series cost data are available in the UK only for payment card frauds (Financial Fraud Action UK), some aspects of identity frauds (CIFAS) and–until 2009 when they were stopped–for external frauds against government departments (UK Treasury). Intermittent or recent data only are available for other data such as social security fraud and error (DWP) and fraud against local authorities and some national non-departmental bodies (Audit Commission, though the future of these after the Audit Commission’s demise remains uncertain). Fraud cost and incidence surveys carried out by accounting firms in many parts of the world are intermittent and have been applied only to large corporate victims (Levi et al., 2007; Levi and Burrows, 2008). And the regular surveys of ‘fraud trends’ in the UK by BDO and by KPMG are analyses of trends in cases coming to court rather than trends in fraud itself. Given the variable probabilities and elapsed times that cases take to come to court, it would be misleading to read them as trends in financial crime. This may seem to be a rather roundabout way of stating that no reliable or valid data exist that would enable us to tell whether fraud or almost any sub-component of it (other than plastic fraud) was changing. However such warnings may be needed because otherwise opinions–however plausible–may be confused with ‘evidence’.

Many estimates of fraud are based on very limited evidence, derive from institutional profile-raising, and take on a life of their own as ‘facts by repetition’, seldom critiqued either by media always hungry for sensational headlines (Levi 2006) or by pressure groups. On the other hand, if we rely on cases brought to conviction, the data may be absurdly low in both harm caused and case complexity. The most subtle cases of fraud and money laundering are hardest to prove beyond a reasonable doubt in the minds of juries or judges, and therefore may not even be proceeded with under the ‘reasonable prospect of conviction’ criterion in the Code for Crown Prosecutors. We must be careful to avoid ‘throwing the baby out with the bathwater’ by using only very low figures from convictions and treating them as ‘the figures’ rather than just treating them as the validated baseline figures (see Levi and Burrows, 2008; Levi and Reuter, 2009).

The elapsed time from fraud to discovery and then from discovery to criminal justice action (if any) means that many of the larger frauds coming to light in 2008–2010 will have been committed some years before. This differs from ‘volume crimes’ such as credit and debit card fraud, which usually come to light promptly (though often not as promptly as burglaries and vehicle thefts). Thus, in the UK, data collected by fraud prevention service CIFAS (2009a, 2009b, 2010a, 2010b, 2011)3 indicate a rise in identity takeover frauds, as ‘new credit’ becomes harder to get, generating displacement to impersonating existing account-holders. Such frauds emerge quite quickly. Since 2006, payment card fraud data in the UK have displayed a broad downwards trend in fraud on lost or stolen cards, due to the introduction of Chip and PIN; a more recent (2009–10) drop in counterfeit frauds on skimmed and cloned cards, which previously had risen substantially, mainly being used overseas to side-step Chip and PIN controls; a slower, modest rise in cards obtained by identity theft; and a less obviously explained very recent drop in card-not-present frauds over the phone and internet. The only type of card fraud having shown an increase in the number of fraudulent transactions between 2009 and 2010 was account take-over (up from 66,000 to 84,000) (UK Payments, 2009, 2010; Financial Fraud Action UK, 2012). In concert with the fall in cheque usage, cheque fraud losses have fallen significantly, while online banking fraud losses rose substantially in 2009 and 2010–perhaps due to improved awareness and reporting, but also reflecting increased phishing for passwords and sophisticated bank site-cloning–before falling, as banks worked harder on prevention.

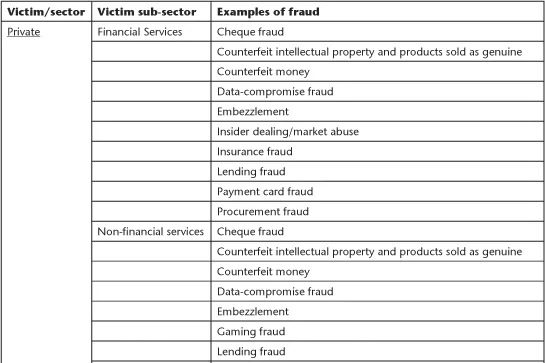

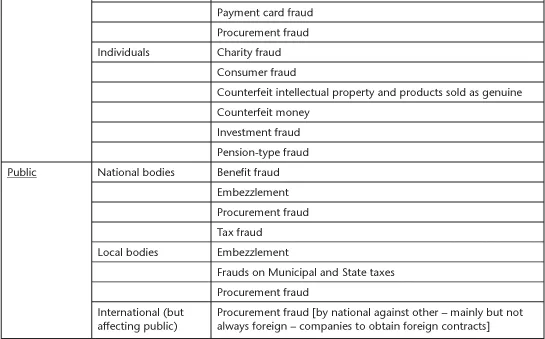

A contrasting example of much longer elapsed time from fraudulent to business-detected awareness is ‘rogue trading’ in the form of illicit (and–perhaps more importantly–unsuccessfully!) betting on market trends, for example by Nick Leeson at Barings in 1995 (http://www.nickleeson.com) and by Jérôme Kerviel at Société Générale in 2007–8.4 In both cases the primary accused alleged that more senior managers turned a blind eye to the risk taking, because they were incompetent (Barings) or because they stood to gain if the risks paid off (both Barings and Société Générale). The popular explanation for this is that it is caused by greed. However, greed is not a helpful discriminator between those who both see and take fraud opportunities and those who do not.5 In essence, they were cases in which ill-supervised traders found ways of breaching their dealing limits without detection and, having lost significant sums in early trading, carried on trading in the hope that they would be able to recoup those losses. Whether others behaved similarly but were more fortunate in their later dealing (or gambling) and remained forever undetected is unknown. Table 1.1 summarises main fraud types by sector.

How widespread are these different sorts of fraud, and what sort of people engage in them? Since 2003, questions about card crime and identity theft have been included annually in the large national sample poll called the British Crime Survey (BCS)–see Table 1.2; and questions about low level fraud and technology crimes were included in the Offending Crime and Justice (OCJ) surveys, but dropped for the years after 2004 (see Flatley, 2007; Hoare, 2012; Wilson et al., 2006; Walker et al., 2009).

Although no studies have been funded by government or the Research Councils of ‘organised fraud’ in the last decade, we know that fraudsters are more diverse in terms of socio-economic status and age than are other ‘organised offenders’, though they sometimes operate in national or ethnic networks transnationally (Levi, 2008a, 2008b). Very serious frauds can be committed by solo actors. According to reviews of its forensic cases by KPMG (2007), typical internal fraudsters act alone, are middle aged and have usually been employed by the company for six or more years; by 2011, this had changed to the typical fraudster acting in collusion and being employed for more than 10 years (KPMG, 2011). Over half commit twenty or more frauds, usually over some years (though these are all people whose frauds are serious enough and whose victims are wealthy enough to engage KPMG).

Table 1.1 A typology of fraud by victim category and activity6

Table 1.2 BCS/OCJ Surveys on plastic card and identity fraud

• There were 1.9 million fraudulent transactions within the UK on UK-issued cards, a decrease of about a third since 2009 (2.7 million). The number of offenders responsible for these frauds is unknown.

• The BCS shows that the risk of being a victim of plastic card fraud increased from 4% among card users interviewed in 2005/06 to 6.4% in 2008/09 and 2009/10, falling to 5.2% in 2010/11. (The proportion who reported they were victims of other property thefts was only 1.1% in 2010/11, so fraud is their most significant theft risk.)

• Considering other types of identity fraud, the proportion of adults who had their personal details accessed or used without their permission in the last 12 months was 6% in 2010/11–up from 2% in 2008/09–of whom half (3%) had actually lost money. In 2008/09, just 1% of adults reported that they had a plastic card used without their permission to make a purchase in the last year. Less than 0.5% said that their identity was used without permission in other ways, for example, to apply for a credit card, mobile phone contract, state benefits, or to open a bank or building society account.

• The pattern of victimisation by age shows a peak in the middle-age groups, falling away for the youngest and oldest. For example, 8.1 per cent of 45 to 54 year old card owners were victims of card fraud compared to 3.5 per cent of those aged 16 to 24 years and 2.6 per cent of those aged 75 years or over. In contrast to other property crime, plastic card victimisation increases with higher household income. For example, 11.7 per cent of card owners in households with an income of £50,000 or more were a victim of plastic card fraud compared with 2.7 per cent of card owners in households earning under £10,000.

• Card owners who had used the internet (but not necessarily to make online purchases) in the last 12 months had higher levels of victimisation than those who had not (7.7% and 2.3% respectively). Of those that used the internet, victimisation was highest for everyday users (8.9%).

• Of those adults who held a UK passport, 1% reported that their passport had been lost or stolen in the previous year. For UK driving licence holders, 2% said that their licence had been lost or stolen during the last 12 months. They probably would not know whether these were used for any criminal purpose.

• From the 2004 OCJS, 1% of 12- to 25-year-olds reported using someone else’s card or card details without the owner’s permission in the last 12 months. The level of card fraud by offenders aged 18 to 25 years remained broadly stable (2% in 2003 and 1% in 2004, not a statistically significant change).

• The 2004 OCJS found that among eligible 18- to 25-year-olds, claiming falsified work expenses and committing insurance fraud was relatively common–admitted to by 16% and 10% respectively. Benefit fraud and income tax evasion were less common (each at 2%).

Technological advances in data linking fuzzy-matching software have shown that what would previously have been seen as isolated frauds, if fraud at all, are actually part of an ‘organised’ network, for example between accident management companies, car hire firms, valuers, and a pool of people willing if asked to make false claims for whiplash and other injuries, implicitly because they do not regard this as seriously immoral. The fact that there ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Contributors

- Acronyms

- Foreword by Monty Raphael

- Book Overview and Structure

- Part I Themes, Trends and Perspectives

- Part II Fraud: How to Investigate …

- Part III Prevention

- Part IV Sanction Routes

- References

- Index