- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rethinking Contemporary Social Theory

About this book

The authors recontextualize contemporary sociological theory to argue that in recent decades sociology has been deeply permeated by a new paradigm, conflict constructionism. Their analysis integrates and sheds new light on eight prominent domains of recent social thought: the micro-level; discourses, framing, and renewed interest in signs and language; the construction of difference and dominance; regulation and punishment; cultural complexity and transculturation; the body; new approaches to the role of the state; and a consistent conflict perspective.

The paradigm combines elements of both social construction theory and conflict theory. It has deep roots in critical theory and more recent links to postmodernism. It is associated with postmodern social thought, although it is less radical and more adaptable to empirical inquiry than postmodernism. The authors tie their new conceptualization of social theory to contemporary applications of social theory in everyday life.

Features of this text:

The paradigm combines elements of both social construction theory and conflict theory. It has deep roots in critical theory and more recent links to postmodernism. It is associated with postmodern social thought, although it is less radical and more adaptable to empirical inquiry than postmodernism. The authors tie their new conceptualization of social theory to contemporary applications of social theory in everyday life.

Features of this text:

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rethinking Contemporary Social Theory by Roberta Garner,Black Hawk Hancock,Grace Budrys in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Paradigms

Introduction to Part I: The Premise and the Project

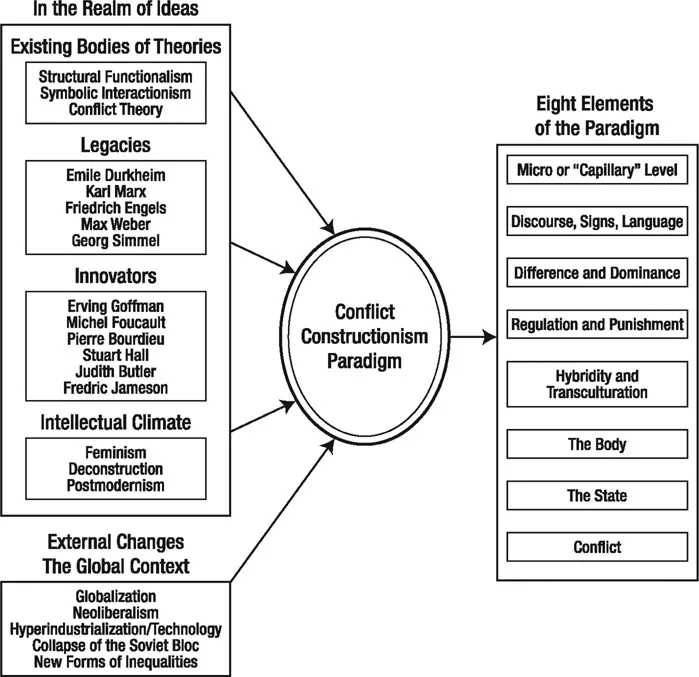

We suggest that in recent decades sociology has been deeply permeated by a new paradigm, conflict constructionism, which is characterized by several defining features: attention to the microlevel, analysis of discourses or frames and a renewed interest in signs and language, examination of the construction of difference and dominance, attention to regulation and punishment, interest in cultural hybridity and transculturation, a focus on the body, new approaches to the role of the state, and a consistent conflict perspective.

The paradigm combines elements of both social constructionist theory and conflict theories. It has deep roots in critical theory and more recent links to postmodernism. It is associated with postmodern social thought, although it is less radical and more adaptable to empirical inquiry than postmodernism. The paradigm incorporates elements of Marxist analysis but adjusts them to new global realities and eschews old orthodoxies. In the historical trajectory of many subfields of sociology, conflict constructionism emerged after an intense engagement with conflict theories in the 1970s and early 1980s, which in turn contested the structural functional paradigm of the immediate postwar period. We identify causes for this paradigm shift, which include the contributions of specific individuals, the general intellectual climate, and various social changes, such as globalization and neoliberalism. Conflict constructionism emerged to address puzzles and problems in the conflict paradigms of the 1970s. As a result, old perspectives were reevaluated, presuppositions were rethought, and new tools for social analysis emerged to confront these new conditions.

Conflict constructionism is not a single monolithic paradigm that claims to have solved all puzzles posed by the social world. Rather it is a cluster of perspectives, a loosely connected web of ideas woven together from the work of theorists who have influenced each other without forming a tightly knit community of the like-minded. For example, Erving Goffman and Michel Foucault independently seized on the treatment of the “mad” as a key to understanding power, regulation, and the construction of deviance. Yet, despite differences in their approaches, the intersections of their ideas yielded new webs of connections across disciplines, and new theoretical framings emerged to speak to multiple audiences.

The subfields of sociology differ markedly in the degree to which they have embraced this new paradigm as a whole, accepted specific elements of it, remained unaffected, or rejected its ideas. In the second part of the book, we examine differences among fields in the ways the new paradigm has been integrated. Sometimes it has come to dominate the field in areas such as the analysis of ethnoracial and gender inequality, culture in the global system, media studies, and the analysis of the self. This type of paradigm shift often reflects massive social change. In other fields, older mainstream theories coexist with the new paradigm, either in harmony or in contention with it. In yet other fields, its impact is limited or contained—and largely confined to new exploration of macro/micro linkages. In at least one field, the sociology of health, a striking reconfiguration of the uses of theory—new or old—has taken place.

Our project is to provide an overview, or map, of the multiple developments that emerged and coalesced into what we have labeled “conflict constructionism” in order to gain a better sense of our bearings within this new intellectual territory. We do not advocate for conflict constructionism; we only seek to chart it and to provoke discussion of changes in sociology.

We hope to create dialogue among different subfields of sociology, to prod sociologists into reflection on their common assumptions, their differing methods, and ways in which they may speak to each other. Whether conflict constructionism is the new paradigm of sociology or already outdated, whether one agrees with our overview or rejects the summation, we use this opportunity to open further conversations.

Part I, “Paradigms,” provides an overview of conflict construction. Here we provide a model for thinking about social theory and discuss the ways changes in theory can be conceptualized. We examine how theories permeate fields of knowledge and the meaning of the term “critical” in social inquiry (Chapter 1, “Paradigms in Sociology”). Having established our model, we turn to conflict constructionism itself and address the eight elements we identify as its defining features, accompanied by empirical examples (Chapter 2, “Conflict Constructionism: Elements of the Paradigm”). Finally, we provide an overview of the key theoretical innovators who contributed to conflict constructionism, examine the intellectual and sociohistorical political and economic forces that sparked it, and explore its impact. Finally, we discuss whether new modes of thinking add up to a paradigm at all (Chapter 3, “History of a Paradigm”).

Part II, “Paradigm Change in Selected Subfields,” explores the impact of conflict constructionism on ten subfields of sociology. Section 1, “Deep Impact: The New Paradigm Becomes Dominant,” explores the analysis of race-ethnicity and gender, culture in the era of globalization, media and information, and the self as personality and person. These fields are seen as having embraced conflict constructionism wholeheartedly, largely as a result of massive social change, and as a result have been the most revolutionized by its ideas. Section 2, “Paradigms in Play,” looks at fluid and sometimes unstable and contentious relationships between old and new paradigms in the fields of political sociology and collective action, urban sociology and spatial analysis, and deviance. Here we see, rather than a full embrace of conflict constructionism, a selective engagement with various elements of the paradigm, sometimes in a harmonious mixing of mainstream and new approaches (e.g., in political sociology and the study of collective action) and sometimes in contention. Section 3, “Paradigm Limited,” probes the areas of inequality, social class, and the sociology of families and traces how, in these fields, conflict constructionism has a limited impact. Mainstream approaches remain very strong, and the influence of conflict constructionism can be mainly seen in the dissection of macro/micro linkages. Section 4, “Paradigms Reconstituted in a Transdisciplinary Field,” is a detailed case study of how one area of sociology has been transformed in the way that theories are deployed. Largely as a result of interdisciplinary collaboration, the field tilts toward a grounded, concept-driven approach rather than embracing any one complete theoretical framework.

The conclusion considers the impact of the new paradigm, assessing whether it contributes to progress in our understanding of society.

A summary chart follows to help the reader navigate Part I.

Origins and Elements of Conflict Constructionism

Source: Dan Causton.

Chapter One

Paradigms in Sociology

Introduction

In order to obtain a better grasp on the new paradigm presented here—conflict constructionism—we must step back and reflect on the notion of social theory itself. More specifically, we need to think about thinking, to reflect on the ways we go about theorizing. We should begin by asking a few simple, essential questions about theory itself: Why and how do scientific theories change? Is change in the social sciences similar to change in the natural sciences? What do we mean when we use the term “paradigm”? How does theory help us understand the world around us? How does theory change as the world changes? In order to make sense of these broad questions and to establish a vocabulary and set of concepts for discussing change in theory, we first discuss Thomas Kuhn’s seminal 1962 study, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

Thomas Kuhn and The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

In his groundbreaking The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn (1962) argued that science has moved forward not only by the steady accumulation of new empirical data and research findings but by shifts in paradigms, the large frameworks that organize thought and specify methods in fields. For example, physics moved from Ptolemy’s model of the solar system to the Copernican model and then from Newtonian physics to Einstein’s theory of relativity and eventually to quantum mechanics.

Sometimes the new paradigm replaces the old one; no one is likely to return to a Ptolemaic view of the cosmos. But in many other instances, older paradigms become “local” theories that pertain to a limited set of phenomena, to a specific “region of reality.” For example, Newtonian mechanics is still enormously valid and useful for understanding the flight of rockets. Even if we live in a probabilistic quantum universe, we do not need to use either Einstein’s theory of relativity or the paradigm of quantum mechanics to design bridges or launch the space shuttle. (In-depth discussions of this issue appear in Camilleri 2009 and Ford 2011; a decidedly maverick and provocative view of scientific “progress” can be found in Feyerabend 1975.)

Why do paradigms shift? Kuhn carefully addresses the question of why paradigm shifts occur. He argues that unsolved puzzles accrue in the field, and as researchers find increasing problems in explaining a phenomenon with existing theories and models, they eventually have to make a leap to a new framework. Paradigm trouble often starts with anomalies, small empirical findings that don’t fit with theoretical predictions and with existing empirical knowledge. Such anomalies accumulate and become increasingly hard to dismiss. Eventually scholars see them as “a problem”—a finding that cannot be understood within the existing theories. The anomalies finally come to be seen as an unsolved puzzle that challenges existing ways of thinking and conducting research. For example, in physics, anomalous results such as the duality of the particle and wave characteristics of light and the puzzle posed by electron orbits within the atom contributed to the shift from classical physics to quantum physics in the early part of the twentieth century (Grometstein 1999).

But the puzzles that are unsolvable within a particular paradigm are not just given by nature; they become identified as unsolvable puzzles by the community of scientists. A social and interactive process among researchers moves toward labeling a phenomenon an unsolved and currently unsolvable puzzle. Solving it—encompassing it within a satisfactory theoretical framework—often requires not only changes in concepts and models but new methods of research as well.

Dominant or contending paradigms? Not all fields have a single dominant paradigm. As noted above, multiple paradigms may provide insights into different phenomena—for example, at different orders of scale. Quantum mechanics is not needed for routine puzzle solving on the scale of planetary phenomena. Relativity is not necessary for applied physics and engineering in the “local” environment. But a discipline can encompass multiple paradigms for other reasons as well. The existence of several paradigms and absence of a dominant one is particularly pervasive in the social and behavioral sciences. These fields are marked by contending paradigms and difficulties in getting rid of paradigms that some believe are no longer intellectually convincing. The overarching reason for the contentious situation, the uneven ripple of paradigm shifts in the field, and the existence of multiple paradigms, often with ill-defined and overlapping boundaries, is that human beings are the subject matter of the social sciences. These troublesome subjects of the social sciences are in turn associated with two major problems that hamper the establishment of dominant paradigms: the historical context of all human action and the problem of objectivity.

The social sciences are historical sciences; therefore their paradigms must change with history. This statement may shock the reader who became interested in sociology because it is about the issues of today! Yet even if we are not historical sociologists, we have to be aware of the historical changes that led up to the conditions we are studying now. The social sciences—and sociology in particular—are about historically situated phenomena. The subject matter of most of the social sciences changes with human history. Many behavioral science paradigms (those that guide psychological research) are largely or partially ahistorical, but few social scientists claim to follow theories or explanatory models of behavior without reference to history; exchange theory and rational choice theory are among the few making this claim because they posit relatively unchanging individual motivations. Many sociological theories are tightly linked to historical analysis—for example, both Marxist and Weberian theories and their offspring, such as world-systems theory, are specifically focused on historical change. Most paradigms in the social sciences include at least some reference to social change, and for this reason, social science paradigms are more fluid than those in the natural sciences.

Objectivity, knowledge, and ideology. Without exaggerating the problem of objectivity in the social sciences, one must concede that the contentious state of paradigms in these fields is partly due to the blurry boundaries between theories or paradigms and ideologies. Many social scientists believe objectivity in the pursuit of knowledge should be an ideal in the social as well as the natural sciences. But theories emerge from theorists’ own experiences and social location, making objectivity more difficult. An even more serious problem with achieving objectivity is that contending theories about human action and societies—unlike theories of astrophysics or quantum phenomena—produce contending plans for practices, policies, and courses of action that impact human beings. (The reader may point out that theoretical physics contributed to the making of atomic weapons, but the contentious issue in that case was the application of the theoretical knowledge, not the objectivity of our understanding of the atom. Yet even that is not as simple as one might think; see Camilleri 2009.) For example, contention between efficient market theorists and neo-Keynesians has implications for human action and well-being. The issue of objectivity is in turn linked to disputes about methods and the larger question of whether the natural sciences provide a viable model for acquiring knowledge about human beings at all. These disputes are often built into paradigms, which are not only different explanatory frameworks but fundamentally different views of the nature of knowledge and inquiry.

Practitioners and paradigms. In addition to these two fundamental intellectual barriers to establishing a long-term dominant paradigm in the social sciences, the history and formation of social sciences disciplines is also a barrier. In a large field such as sociology, there is not one all-encompassing community of scholars but many loosely linked groups identified with subfields, such as sociology of health and illness, sociology of family life, urban sociology, and so on. In turn, the various subfields of a discipline have their own communities of scholars, which are formed in different ways and have different links to closely related fields. Subfields of sociology have different histories, and some have links to applied fields, such as criminology, social work, and public health—human disciplines in which both practitioners and those on whom they practice engage in contention over ideas and policies. The communities of scientists who constitute subfields are different and have markedly different orientations toward the available paradigms.

For these reasons, it is difficult to establish a single dominant paradigm in the social sciences. Sociology only briefly enjoyed paradigm dominance for a few years after World War II when in US universities, structural functionalism appeared to be very popular. But its dominance faded quickly, and since then the field has been contentious and organized around many paradigms.

A New Paradigm in Sociology?

Examining trends in concepts and theories over the past half century, we can discern the emergence of a paradigm, conflict constructionism, that permeates many areas of contemporary sociology. In the following pages we trace the circumstances in which this paradigm appeared and discuss the extent to which it transformed subfields of sociology. It has influenced theoretical and empirical work without emerging as the recognized dominant paradigm that commands scholarship throughout sociology. The purpose of the analysis is not to defend conflict constructionism but to argue at a metalevel that this set of overlapping premises and ideas came to constitute a paradigm that guides sociology and many of its subfields. We use Kuhn’s (1962) analysis of paradigm shifts to explore how this approach can help us understand changes in the field of sociology.

The owl of Minerva flies at dusk, and sometimes it is possible to recognize a paradigm only after it has been in use for a while—perhaps when it is about to fade away or come under attack. In 1959 Kingsley Davis, a leading theorist of the post–World War II era, published “The Myth of Functional Analysis as a Special Method in Sociology and Anthropology,” arguing that functional analysis was not a method in the social sciences but the method and that the dominant theoretical and explanatory paradigm of the disciplines was functionalism. This article, based on Davis’s presidential address to the American Sociological Association, summed up and celebrated the fundamental paradigm of the late 1940s and 1950s, the exciting y...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Paradigms

- Part II Paradigm Change in Selected Subfields

- Conclusion

- Glossary and Concepts

- References

- Suggested Readings

- Index

- About the Authors and Contributors