![]()

Part I

Media Production

Part I is called “Media Production” because the guidelines are written to explore basic principles of the creative process common since the early days of modernism when mechanical reproduction became part of daily reality. Each chapter offers guidelines for projects that can be produced with any basic software, such as Photoshop, or Illustrator—but they could also be realized with analog technology: basic cutting and pasting of common print material, or repurposing drawings or other forms of media of choice. The fifth chapter is more abstract and theoretical, bringing together many of the concepts discussed in the previous chapters. The first part ends with a theoretical essay, “Modernism and Media Production,” which is a critical and theoretical reflection on the history of the creative approaches discussed throughout the chapters.

Chapter 1, “Randomized Signification,” focuses on open-ended exploration of media production according to chance and free association. The methods and history discussed are relevant to contemporary art and media design because current aesthetics in media at large are informed by experimental approaches that in the past appeared to detach the artist from the work they produced. This interest in detachment in turn has been passed on to algorithms performed by computers. With this in mind, the open guidelines for this chapter are an introduction to the premise of individual expression that implements systematic methods and rules, developed to set limitations by the artists or designers, in order to produce work that appears to offer some type of detachment from artistic subjectivity. Additionally, the exploration of methods of random association as part of the creative process is important to contemporary creative production because such a deep engagement can function as a critical tool and creative vehicle that enhances the recognition of variables that shape social reality for the production of art and design.

Chapter 2, “Analogized Codification,” considers how image and text are constantly combined (mashed up) in order to communicate ideas for different purposes and interests, from personal messages found across social media to major productions by media conglomerates. The open guidelines in this chapter are designed to explore the relation of image and text in terms of analogical and digital code, meaning by way of comparing elements that may be carefully orchestrated as a visual composition (image) and elements that appear to have been developed arbitrarily but function by way of a syntactical relation (text).1 Understanding the relation of image and text in terms of analogical and digital code is foundational to contemporary art and media design because they are elemental forms of communication.

Chapter 3, “Sampling Creativity,” focuses on the reinterpretation of previously existing concepts and material forms for creative production. The open guidelines for this chapter are designed to explore how new content is developed. The creative processes that make new content possible are material sampling and cultural citation. Understanding how creativity takes place based on sampling and citation is important in order to consider how what an individual may produce is a unique instantiation—an intensity of many things that come together at one point to present a concrete object (material or immaterial) that is then contemplated or put to use, depending on the object’s purpose and cultural value.

Chapter 4, “Vectorial Pixels,” considers how common perceptions of photographs and drawings are evaluated and legitimated in culture based on an implicit understanding of both forms being reconfigurable. The common understanding of both forms being editable was not always the case prior to the ubiquity of computing in daily life. The point in this chapter is to explore the creative possibilities of images that may be perceived as photographs, drawings, or a combination of both in terms of indexicality and selectivity; meaning whether or not an image appears to be a denotative or evidentiary presentation of a subject over a representation that appears to be a selective or stylized composition. The guidelines in this chapter are designed for the critical awareness of the popular binary at play in manual analog production and digital reproduction that remains part of the cultural understanding of images of all types.

The goal of Chapter 5, “Bifurcated Meaning,” is to evaluate slippage of meaning in creative practice. It focuses on how artists and designers continually find ways to manipulate the potential interpretation of their works so that their points of view may be shared as clearly as possible, even when such readings are open-ended. This is often achieved with the deliberate implementation of ambiguity as a means for possible multiple readings of works of art and design. To engage with the process of signification, this chapter considers basic principles of poststructural theories, which have played an important role in creative production since at least the second half of the twentieth century.

The last chapter of Part I, “Modernism and Media Production,” reflects on some of the main premises discussed throughout Chapters 1–5. It contextualizes chance and randomness, analogical and digital code, material sampling and cultural citation, as well as the slippage of meaning in direct relation to the integral role that appropriation and remix play in the creative process since the early days of modern media.

Note

![]()

1

Randomized Signification

Elements for Exchange

Premise: This chapter explores methods of chance and free association for the recombination of image, sound, and text in contemporary production of art and media design.

The recombination of pre-existing elements in ways that appear random or with no clear logic was explored in depth across the visual arts with collage during the early part of the twentieth century. There were many approaches to working with pre-existing material, some which included methods of randomization and free association that led to works of art that were reflective of the social experience of modernity and modernism by avant-garde artists and writers.

Random signification, that is, the creation of meaning with an apparent aleatory process, became of specific interest to Dadaists and Surrealists during the first half of the twentieth century. Avant-garde artists between the 1910s and 1930s explored systematic methods for art production, which in current times are emulated with computer algorithms. These methods include automatic writing and drawing, which can be considered a way of brainstorming to develop material that in turn can be further manipulated. An approach that was of interest to surrealists in particular that made its way to later art production is the exquisite corpse, which consists of making part of a drawing to then pass it on to another participant who would not see all of what had been drawn, but just enough to compose his or her own contribution, to then pass the drawing on to another collaborator.1 The end result in such process was works that were not direct representations of reality, but rather an exploration of visual language by a collective of artists. This approach was developed from a parlor game in which a person wrote a word, which was covered, and the paper was passed to the next person who would write a random word, to then have it covered; this process was repeated until all participants contributed. The result was a random sequence of words that made no sense. This arbitrary approach is closely linked to the principles of chance.

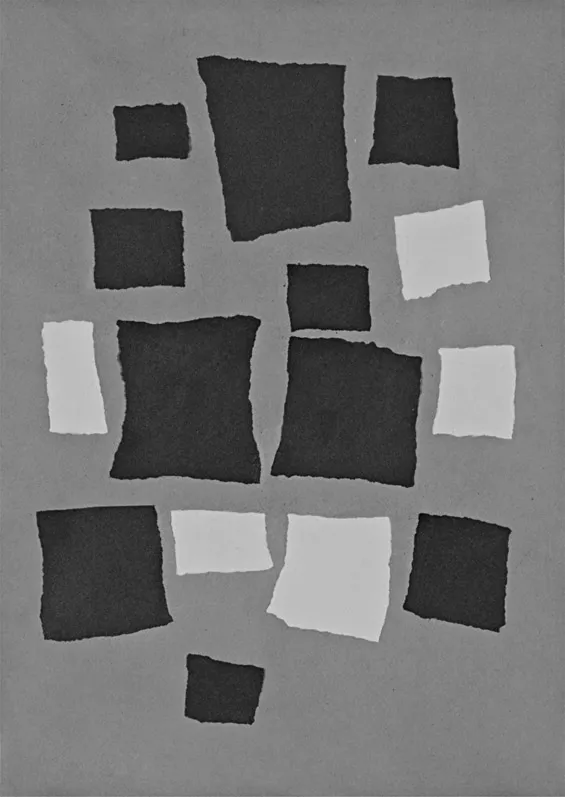

Chance specifically played a major role for Dadaists and it would prove to be an important element in art production throughout the twentieth century. Chance as a creative method consists of setting parameters that allow anything to happen, within defined boundaries, and to include whatever outcome as the work of art. Jean Arp, for example, implemented chance to develop visual works. His Collage with Squares Arranged According to the Laws of Chance (1916–1917) (Figure 1.2) is a composition of colored papers cut by hand into rough squares. Arp claims to have been struggling with a drawing, which he eventually tore up; when he let the pieces fall to the ground he saw the composition that resulted in the collage.2

Figure 1.1 Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors Even (The Large Glass) (1915–1923). Oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust on two glass panels, 9 feet 1 1/4 inches × 70 inches × 3 3/8 inches (277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm).

Figure 1.2 Jean Arp, Collage with Squares Arranged According to the Laws of Chance (1916–1917). Torn-and-pasted paper on blue-gray paper. 19 1/8 ´ 13 5/8 inches (48.5 ´ 34.6 cm).

Marcel Duchamp, who was also part of Dada, used chance in his art production. 3 Stoppages Etalon (1913–1914) includes three threads glued to three painted canvas strips mounted on glass panel. Duchamp claimed that the threads’ shape were defined by how they fell on the canvas strips.3 Duchamp also let chance play a role in the completion of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors Even (The Large Glass) (1915–1923) (Figure 1.1). He considered the work “definitely unfinished” when it was dropped, producing large cracks on the upper half of the composition.4

Tristan Tzara, a Dadaist poet, applied a similar method to writing. He cut words from newspapers, which were shaken and dropped on a table. Based on their arrangement Tzara wrote poems. This approach would become influential for experimental writers, such as William Burroughs, who makes direct reference in his text “The Cut-Up Method of Brion Gysin” to an incident in which Tzara proposed to fellow surrealists to create poems by taking words from a hat, for which Tzara was excommunicated from the group.5 Burroughs, in turn, wrote about the cut-up method, which he credits to Brion Gysin. Burroughs claims that he used the cut-up to develop some of his own writing including Naked Lunch as well as Minutes to Go and The Exterminator.6 The cut-up method consists of taking a written page and cutting it into at least four parts, which are then rearranged: section 1 matched with section 4 and 3 with 2. This process could be adjusted as needed, according to Burroughs, but the point is to include a random element in the creative process. He explains that “You cannot will spontaneity. But you can introduce the unpredictable spontaneous factor with a pair of scissors.”7 Scissors happen to be the tool of choice in Burroughs’s case, but the cut-up as a conceptual method can be implemented with any technology.

John Cage is considered one of the most important creative figures of the twentieth century. He was primarily a music composer who relied on chance to develop much of his creative work. He collaborated extensively with major figures in the visual arts, modern dance, and theater. Cage thought about what most people would call noise to be a form of music. He found orchestration in nature. Cage’s exploration of chance led him to be associated with various collectives including Fluxus, as well as Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT). One of his best-known works is 4’33”, a music performance consisting of a musician sitting in front of a piano ready to play but never doing so. The audience tries to remain quiet for the entire time of the music performance; yet the sounds in the room—coughing, fidgeting, whispering, breathing, shuffling of feet, and so on—become part of the musical composition. This composition could actually be performed by anyone for any audience with any instrument, and for an arbitrary amount of time. Cage also performed several “variations” throughout the 1960s consisting of random noise produced with radios and all types of rudimentary objects in public spaces from art galleries to philharmonic halls.8

Random signification in close relation to chance remains an important method to develop creative work. In terms of computing, it is the common random algorithm that is often used in works tha...