- 908 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gower Handbook of People in Project Management

About this book

Modern projects are all about one group of people delivering benefits to others, so it's no surprise that the human element is fundamental to project management. The Gower Handbook of People in Project Management is a complete guide to the human dimensions involved in projects. The book is a unique and rich compilation of over 60 chapters about project management roles and the people who sponsor, manage, deliver, work in or are otherwise important to project success. It looks at the people-issues that are specific to different sectors of organization (public, private and third sector); the organization of people in projects, both real and virtual; the relationship between people, their roles and the project environment; and the human behaviours and skills associated with working collaboratively. Thus this comprehensive and innovative handbook discusses all the important topics associated with employing, developing and managing people for successful projects. The contributors have been drawn from around the world and include experts ranging from practising managers to academics and advanced researchers. The Handbook is divided into six parts, which begin with management and project organization and progress through to more advanced and emerging practices. It benefits hugely from Lindsay Scott's expert knowledge and experience in this field and from Dennis Lock's contributions and meticulous editing to ensure that the text and illustrations are always lucid and informative.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gower Handbook of People in Project Management by Lindsay Scott, Dennis Lock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Management and Organisation

CHAPTER 1

People and Project Management

The human race has an incredible ability to innovate, adapt, change, develop and create. We do this by making change – from slow gradual change (for example by migration towards cities) through to more immediate, identifiable change (such as the development and implementation of technologies). It is these more immediate, identifiable changes that we now regard as projects, with all the defining characteristics of scope, time, cost and so on that have become so familiar to project practitioners. In consequence we have allowed these characteristics to influence the way in which we define and perceive the roles that people are given (such as project manager) and the general approach taken (for example, project management). Further distinctions have emerged around programmes and portfolios.

In spite of this progression and in particular the development of the science of project management, there has unfortunately been no significant improvement in the probability of project success. For example, in the UK public sector there has been a stream of critical reports (from sources such as the National Audit Office and Public Accounts Committee) on the failure of projects, programmes and other change initiatives. These criticisms range over many kinds of projects, from defence to IT. But, of course, project failures are not confined to the public sector. There have also been many examples of failed projects in the private sector, although these have not always been so well publicised.

Critical reports of projects often point to cultural and behavioural issues being significant factors in poor project performance, stemming from the important and constant factor present in all projects. That crucial factor is the involvement of people (which of course is the focus of this Handbook).

In the 20th century and earlier, the ‘people aspect’ of projects was a relative sideline for most practitioners in the project world. Although there were exceptions, the primary focus was on using the best methodology and tools to deliver success. Of course, advances in project management practice in recent years have been very important, enhanced by the rapid advance of communications and IT. But attention is turning to how people perform in projects, and how we can manage projects and programmes to improve the performance of individuals and teams. So the study of people in project management has rightly become a growing area of interest and development for the profession, as evidenced for example in training and the publication of articles in professional journals and other works such as this Handbook. However, for centuries project management in many ways defined itself by the process-driven elements, the so-called ‘hard side’ of project management, and it is still finding it difficult to shake off that brand.

‘It’s all about the people’. This, or some similar phrase, is used increasingly as those involved in the delivery of projects realise that ultimately nothing happens on a project unless it is made to happen by people (or, to put that more accurately, by each of the individuals who contribute directly or indirectly to the project). Therefore, what people do on a project, and crucially how they do it, should be the primary concern of those who manage and lead projects. An energised team can enable apparent miracles to be achieved. But without that team effectiveness, even the simplest of changes can turn into a disaster for the individuals and organisations involved.

This introductory chapter is for practitioners who wish to understand the impact of how people perceive, value and embrace what we relate to as project, programme and portfolio management. By offering a model which project practitioners can use to reflect on their own projects my aim is to help identify where insights can be found to make desired change happen more effectively – which is precisely what we are all ultimately aiming to achieve as project practitioners.

Management Challenges Specific to Projects

It is worth considering for a moment what it is about the management of people to deliver change through projects that is so much more challenging than managing people in functional or other steady state contexts.

Whether they are project or functionally based, most managers in an organisation have to deal with a high level of change. That change can be driven by different factors for each organisation, which might include for example:

• the need for constant innovation and improvement;

• increasing scrutiny of performance;

• shortening product and service life cycles, and so on.

The key distinction within projects is generally the rate of change and the complexity of relationships involved in delivery. The full range of challenges associated with managing people in projects is vast. However, I highlight in the following lists a few of the unique project complexities that we must recognise as influencing the relationships that today’s project management practitioner must manage.

Organisational Context

• The need to understand many organisational models and the cultures that underlie them;

• the dynamic nature of project organisations, which can constantly change in size and shape through the typical project life cycle;

• complex nature of ‘success’ – defined not as a single entity but as a diverse range of transitory perceptions held by the broader stakeholder group;

• the need to have a focus on and understanding of the business context to ensure that decisions are made from the perspective of project outcome and benefits realisation;

• expectation by all those involved in the change process for high levels of openness and engagement, whether from those working directly on projects or from those who will be affected by the eventual change.

Managing Up

• Difficulty of uncovering what drives the opinions/decisions of stakeholders and discovering their relative levels of power and influence;

• need to ‘sell’ the vision through the stakeholders to secure the essential levels of direct and indirect support;

• recognising, valuing and marshalling the subjective views of customers and stakeholders;

• translating the ‘political’ into a reality – understanding and then transforming organisational strategies and expectations into not only technical but also politically feasible solutions that are supported by stakeholders.

Managing Down

• Influencing teams without traditional positional or hierarchical authority by developing and utilising stakeholder relationships;

• need to lead teams so that they become greater than the sum of their parts to offset resource shortages and can deal with the need to meet challenging objectives;

• ability to deal with high levels of uncertainty and often relentless change – which can be disconcerting and challenging for many people to deal with;

• accept and work with the inevitable resistance to change;

• ultimately the need to model constantly what you say in the behaviours you exhibit. This is a critical requirement for a leader of change.

Impact of People in Project Management

‘People focused’ is one of a number of terms and phrases used to describe the human aspect of project management. Alternatives include the ‘soft side’, ‘people side’, ‘behavioural side’ and a host of others, some less descriptive and more critical. The phrases are used without reflecting on their meaning or how they might be interpreted by others. By using these widely adopted phrases we tend to convince ourselves that we fully understand what these ‘people aspects’ are and how they affect project performance. But that is not yet the case. The interactions and dependencies of people in projects are only now being identified, questioned and understood. For example, how does the motivation of an individual affect the way in which he or she plans? Or, how is portfolio management accepted by an organisation in which the culture is not geared to objective decision making?

Projects, as I have said, are for and all about people. Therefore we must understand what we mean when referring to ‘people’ (from the individual right through all the different collective layers of teams and culture). We have to learn and understand the influence that people can have on projects, the roles inherent in the change process and how project management is defined and used.

A Model for Analysing and Improving Relationships between People and Projects

The challenge now (and one that this chapter addresses) is how do we take these people aspects and make them part of what we call the field of project management? Not a separate, stand-alone consideration, but central to how we define change, the processes we use and the roles undertaken.

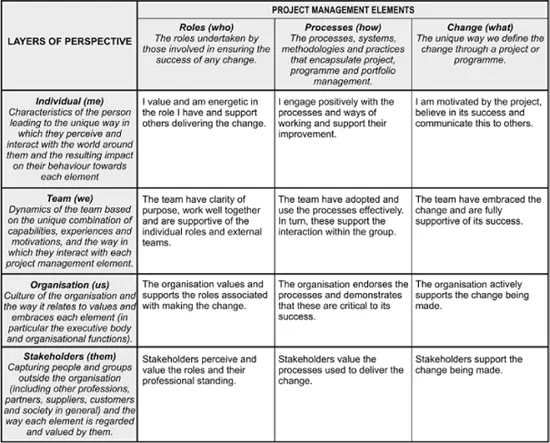

To help achieve this I shall use a practical model that describes the interplay between the different elements of project management and the layers of perspective from the multiple groupings of people involved. The following explanations will make this clearer:

• Layers: the different layers of perspective brought by individuals, and then progressively by teams, organisations, and ultimately by the collective group that I have referred to as stakeholders. Other layers could be added but I consider these sufficient for the purpose of this model.

• Elements: which is a way of looking more broadly at what we define the field of project management to be in terms of the roles, the change we are looking to make and how we go about making that change.

When these layers and elements are combined, we have a model which can be used to map out the impact of people on the world of project management. First, here are the layers:

• Individual (me): characteristics of the person leading to the unique way in which they perceive and interact with the world around them and the resulting impact on their behaviour towards each element.

• Group or team (we): dynamics of the group or team based on the unique combination of capabilities, experiences and motivations and the way in which they interact with each project management element.

• Organisation (us): the organisation and the way it relates to, values and embraces each element (in particular the executive body and organisational functions).

• Stakeholders (them): capturing people and groups outside the organisation (including other professions, partners, suppliers, customers and society in general) and the way each element is regarded and valued by them.

Now, secondly, I list the elements that define the field of project management. For simplicity I shall refer only to projects, but the following in most cases relate also to programme and portfolio management. Here are the project management elements:

• Roles (who): the roles undertaken by those involved in ensuring success of any change.

• Processes (how): the processes, systems, methodologies and practices that encapsulate project, programme and portfolio management.

• Change (what): the unique way we define the change through a project or programme.

Figure 1.1 A model of people in projects: Statements to consider

Source: © 2013 Team Animation Ltd. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.

It has not been possible to amend Figure 1.1 for suitable viewing on this device. Please see the following URL for a full size version http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781317125198fig1_1.pdf

Figure 1.1 displays the above relationships in diagrammatic form. The model can be approached and applied in multiple ways. Its primary use is to help individuals, groups or organisations to question and understand the impact caused by the interplay between each layer and the processes’ roles involved. Each of these interplays can be a source of discussion and an opportunity for improvement if challenges and issues are mapped to the structure.

Practitioners will be able to identify with parts of this model. When ‘people aspects’ are explicitly brought into discussion, either in projects or within the profession, this often refers to the first two rows and the first column (the individual or team in terms of their roles).

You will probably be familiar with training, workshops or tools covering areas such as personal skills, forms of leadership, team structures and dynamics, and so on. Many chapters in this Handbook will each cover one or multiple interfaces in the model. As an example, ‘project leadership’ primarily focuses on the individual and the role that he or she undertakes. However, discussion on people in projects rarely extends beyond these boxes. But we need to examine broader aspects, where we can begin to gain a deeper understanding of the rich interplay between groups and organisations and what we call the ‘field of project management’.

In recent years as our profession has started to gain an understanding of the way organisations relate to project management – some seem able to adapt effortlessly and adopt and sustain a project-based way of working. But others find it challenging and a continuous source of friction. In the past there has been too much of a ‘one size fits all’ mentality, without taking in to account the culture of the organisation and the unique context within which it finds itself. This is an emerging field of organisational project leadership, on which I am working with a number of business schools to develop our knowledge and thinking.

USING THE MODEL

To make the foregoing useful for practitioners, the model asks the practitioner to reflect at each point of interface between a layer and an element on a recent change in which they have been involved. These statements describe a situation between the individual, the team, the organisation or stakeholders that is likely to be positive and favourable, where each layer is positively supporting and engaging with the roles, processes and entities. The practitioner must now consider each statement and answer honestly ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

This, therefore, has provided the project practitioner with a means for assessing her/his own situation in order to identify where action can be taken to further develop and improve the situation. As an example, people who have used this model as described have identified the following:

• The impact that their own feelings have had on not only how the project has proceeded but also ultimately on the outcome. For example, how personal fears regarding failure resulted in a downscaled (descoped) project.

• How success is viewed very differently in other people’s eyes, and the lack of consideration often given to this. For instance, in one case only after the project was well under way did the true feelings of key stakeholders become evident, which resulted in considerable disruption and change.

I propose the following four-stage process as a means for using this model (Figures 1.1 and 1.2) effectively. I have included this here by prior agreement with Team Animation:

1. Distinguish

Consider the context within which you work and the change you wish to consider.

2. Assess

Read each statement in the model (Figure 1.1), beginning top left with ‘me and my role’, progressing from left to right before considering ‘us and our roles’ and so forth. You can either agree or disagree with each statement.

3. Diagnose

Based on your responses, carry out a simple diagnosis of the situation.

• Out of a possible 12 positive responses, how many of the statements in Figure 1.1 did you fully agree with?

• Based on this score, would you say the performance of the project is represented by t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on the Contributors

- Preface

- Part 1 Management and Organisation

- Part 2 People in and Around the Project Environment

- Part 3 Improving Project Teams and Their People

- Part 4 Developing the Individual

- Part 5 Project Staffing and HRM Issues

- Part 6 More Specialised Topics

- Bibliography

- Index