- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This text explores the industry of low-power television (LPTV) in America. It covers what LPTV is and how it got started, who the broadcasters are and their viewers, LPTV's significance in contemporary society and culture, and the challenges it faces in the late 1990s and the millennium.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Hidden Screen by Robert L. Hilliard,Michael C. Keith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

—1—

A New Medium

The Nature and Purpose of Low-Power Television

LPTV Characteristics

Low-power television stations are regular broadcast stations that operate with greatly reduced power compared to that of full-power traditional television stations and that, consequently, reach a much smaller geographical area and a smaller number of viewers.

Low-power television stations or, as they are called, LPTV stations, were designed to provide additional television channels in communities that had available frequencies, but which were too close to other cities with co-frequencies (that is, the same frequency assignments) or adjacent frequencies, so that the addition of any more full-power television stations would interfere with other stations’ signals. Low-power stations in those communities, reaching perhaps from 5 to about 15 miles compared to 40 or 50 miles for full-power stations, are not as likely to create interference. This enables willing entrepreneurs to apply for permits to construct and operate stations where otherwise no additional TV services could be accommodated. Essentially, therefore, serving a limited geographical area, these LPTV stations orient their programming and advertising to a specialized, local audience.

LPTV stations use the same frequencies as full-power stations. To protect stations from interference by other stations, the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has allocated television channels throughout the country on a “domino theory” basis. That is, there must be specified spacing—mileage separation, or distance—between VHF stations on the same frequency and between UHF stations on the same frequency. VHF stations cover a larger geographical area than do UHF stations with the same power. Electronically, the lower the frequency, the further the signal carries through the air. VHF channels are 1 through 13. (Channel 1 was appropriated for federal government use many years ago and is not found on domestic television sets.) UHF channels are from 14 to 83. The channels beyond 83 that some 70 percent of television homes find or will soon find on their sets are not broadcast frequencies but are numbers assigned to cable or satellite channels received through a cable wire, satellite dish, or other non-broadcast means. In some cases a broadcast TV station may be assigned the same channel number it has for its over-the-air signal.

Where two or more cities are closer than the distances specified by the FCC, the same frequency cannot be used in both those cities. In many parts of the country, especially in high-population urban areas, the demand for television stations exceeds the frequency capacity, given the interference restrictions. LPTV solves the problem to a certain extent. By authorizing a low-power station in one or more of those too-close communities, the FCC enables the community to add a station and, because the LPTV range is short, to avoid interference with the signals from co-frequency stations in other communities. LPTV stations are authorized to operate on a “secondary” basis only. If by any chance they do interfere with full-power station signals, the LPTV station must either reduce power to avoid such interference or, if necessary, go off the air. In this respect they are similar to most AM radio stations, which must take measures after sunset to avoid interfering with the signals of stations with broader and more powerful operating parameters. Other comparisons to radio are equally valid and are discussed later.

Service Areas

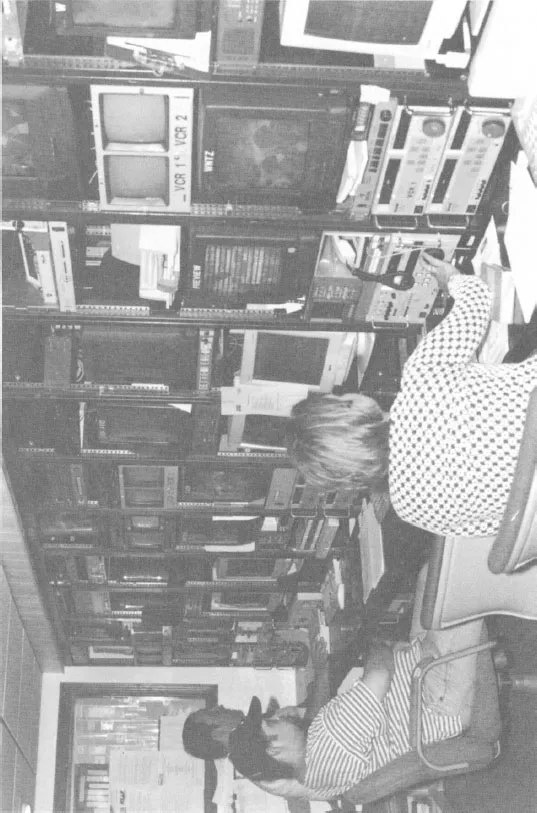

LPTV stations principally serve urban areas with populations substantial enough to provide enough viewers and potential customers to make advertising worthwhile for businesses wanting to sell products or services in that area. However, LPTV stations also serve rural areas (their original target audience) where there is not a sufficient population to warrant regular-power, full-service television stations, which are expensive to build and operate. These geographical areas, therefore, receive little direct broadcast television service. They are dependent on cable companies, which are reluctant to invest large capital amounts in limited potential subscription, low-population areas, and on satellite reception, which, at this writing, is still relatively expensive for the average household and quite expensive for the generally low-income, isolated rural areas. In some of these areas, however, there may be a sufficient population base to support a smaller, relatively inexpensive LPTV station (Figure 1.1).

In some instances LPTV stations serve distinct communities and fill specialized community needs not served by full-power television stations or cable systems, which must serve broad-based audiences to obtain high enough viewer numbers—that is, ratings—to attract advertisers that will pay profit-making commercial fees. Some of these LPTV stations provide non-commercial educational programming in college and university towns, while at the same time providing a practical broadcasting experience for the college or university media students. Some areas simply do not require full-power stations. A 50,000-watt station in a sizable community in certain geographic areas of the country might cover that community very well, but the remainder of its signal might reach only empty plains or uninhabited mountains or large bodies of water. In such cases, the limited signal of an LPTV station could technically serve the intended audience just as well. The drawback for LPTV is in programming; national networks prefer to affiliate only with full-power stations, although the fledgling WB and UPI networks in the early 1990s were happy to find LPTV affiliates in areas where the four major TV networks had already signed up all the existing full-power stations. One of the big four, FOX, did seek out LPTV affiliates when it first began its network operations and tried to break the hold of the big three, ABC, CBS, and NBC. More on the programming aspects of LPTV appears in chapter 4.

The Head Count

According to Broadcasting and Cable, at the end of 1998 there were over 2,000 LPTV stations on the air, over 1,200 of them in the UHF range. This compares with only about 1,560 full-power TV stations—about 690 VHF and about 870 UHF. Although the UHF band, in which the vast majority of LPTV stations operate, comprises channels 14 to 83, the lower frequency UHF channels tend to be utilized whenever possible by the full-power stations because of their stronger signals. Therefore, most of the LPTV UHFs generally are in the 70-to-83 range. The figures reported by the magazine are obtained from the FCC, which LPTV scholar Professor Mark Banks says are unreliable. “In actuality there are far fewer low-power stations operating. Perhaps half the number cited above would be optimistic. The commission doesn’t keep track of the number of LPTVs really on the air at any given time.”1

Figure 1.1 Control of a Multiple LPTV Operation in Loulsiana. Courtesy KLAF.

In Translation

LPTV stations emerged from what are called “translators.” Translators, which have been around since the 1940s, were originally used to repeat the signal from a full-power TV station in areas that the original signal did not reach. By repeating, or “translating,” the signal from the original frequency to one that did not cause interference to other signals in an area, the translator extended a station’s reach to small towns and rural areas that otherwise were out of the range of the signals that originated in distant, larger cities and towns. To further avoid interference, the translators were limited in power and, therefore, distance. Some full-power signals were repeated or translated more than once in order to extend the signals to additional communities. Eventually, in order to serve local needs, some of these translators began to include their own programming, oriented to the targeted audiences. Today, such audiences are able to receive not only broadcast stations, but also cable networks and satellite transmissions. When translators and the subsequent low-power television stations began to develop, however, cable had not yet expanded to most communities and did not have as large a channel capacity as today, and direct broadcast satellite transmission and reception were not yet easily available.

Translators developed quickly in their early days, and by the mid-1950s more than 1,000 were in operation, mostly in rural areas. In addition to their use in the authorized retransmission of signals, many translators began to be used by local groups, such as fraternal and community service organizations, local government offices, and others that wished to provide special material to the people in the area, information that could not be disseminated as quickly or as effectively in any other way.

The translators that operated in this way, programming original material rather than solely retransmitting a distant signal, were not yet authorized by the FCC to do so. Although the FCC licensed translators and established rules governing their operation, no provision had been made for low-power station programming. The FCC, however, was not assiduous in taking action against the translators as long as they caused no interference to licensed stations. On a number of occasions, though, the FCC did object to translators originating programming unless they had specific FCC permission to do so. As might be expected, the fill-power TV stations, in many instances acting through their state broadcaster associations, and represented in Washington, D.C., by their lobbying group, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), took exception to any given instance of program origination by translators (the Corporation for Public Broadcasting took umbrage to the idea on much the same grounds). They feared—and time later proved them right—that given programming permission, the translators might develop into direct competitors for the available advertising and underwriting dollars in their service areas. LPTV approval needed strong backing at the FCC. Robert E. Lee, at that time acting chair of the commission, acknowledged that the broadcast industry would be unhappy if a new, potentially competitive service, LPTV, were established. In supporting LPTV, however, he stated:

When cable first came along, broadcast people didn’t like it and looked on it as a predator of programming. They did their best to stifle it over the years. But when it became obvious to all that it was here to stay, the broadcasters got into it with both feet.2

Authorization of programming on translator frequencies—in essence, the development of low-power broadcast stations—was at first given principally for noncommercial educational uses. In 1966 an educational organization in New York State, BOCES (Board of Cooperative Educational Services), obtained FCC permission to broadcast on their translator systems serving schools in upstate New York, materials from TV station programs and from other sources that they had put together into educational formats. In 1973 the Alaska Educational Broadcasting Commission (AEBC) asked the FCC for permission to develop low-power stations to broadcast programming to the many isolated villages that make up much of Alaska. This system later developed into an extensive network of LPTV stations (several hundred) providing Alaskan communities and individuals with informational and educational materials they otherwise would not have received. Today, however, this use of LPTV in Alaska is no longer necessary for broad dissemination, although it still has value for community station local programming. Almost every village, no matter how small or isolated, has a satellite-receive dish serving all the dwellings in the community. (See chapter 8.)

A Metamorphosis

The increasing demand for permission to use translators to originate programming prompted the FCC to propose, in September 1980, the creation of a special category of low-power television stations, LPTV. These stations would be limited in power and in the mileage area they would be permitted to cover. Technically, they were like translators, operating on the ultra-high microwave frequencies. They would not, however, be limited solely to retransmitting the signals of full-power stations, as were translators, but would be permitted to originate their own programming, like full-power stations. Because of their limited range and because the FCC wanted to facilitate the development of this new service that ostensibly would serve the special needs of communities not provided for by the already existing television systems, the FCC imposed considerably fewer regulations on LPTV than on the full-power TV stations.

In 1981 the FCC began accepting applications for the construction and subsequent licensing of LPTV stations. The first LPTV station was put on the air by John Bolar, an experienced broadcaster, in December, in Bemidji, Minnesota. In April 1982, the FCC published rules governing LPTV and issued the first LPTV station licenses. Any translator station that wanted to convert to LPTV status was permitted to do so simply by informing the FCC of its changeover. By the end of the year almost 400 translators had been licensed to operate as LPTV stations, most of them in rural areas, and more than 200 of them were already on the air. The most significant portents of things to come, though, were the almost 8,000 applications for construction permits for LPTV stations that had been filed with the FCC.

“Low power” is synonymous with “local.” LPTV was not designed to compete with full-power TV stations or with cable systems, although in some fairly rare instances its growth has had that result. Stations were supposed to service, principally, underserved markets. That meant, generally, rural areas. However, it turned out that many urban areas felt that they, too, were underserved—not because there were not enough full-power TV stations in the given market area, but because those stations did not serve the needs of specified groups in those areas; thus, there were applications from urban as well rural areas for LPTV licenses.

Some early definitions of low-power television compared it to cable, insofar as both provided a service to the local community, cable through its mandated access and local origination channels. However, LPTV advocates, while decrying cable’s multiple channel advantage, contend that because LPTV stations’ dedication is local, the latter more effectively reflect and serve their individual neighborhoods and communities. (See this chapter’s appendix for FCC rules and regulations on LPTV.)

Diversity and De...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Chapter 1 A New Medium: The Nature and Purpose of Low Power Television

- Chapter 2 The Screen Over the Fence: The Evolution of Neighborhood Television in America

- Chapter 3 See LPTV Run: Its Organization and Structure

- Chapter 4 And Now the News: Programming for the ‘Hood

- Chapter 5 The Bottoming Line: Subsidizing the Hidden Screen

- Chapter 6 Maintaining the Image: Technical Considerations, Other Micros, and the Future

- Chapter 7 Studies and Briefs: A Comparative Assessment and Civil Action on Behalf of LPTV

- Chapter 8 The Alaska LPTV Network

- Notes

- Further Reading

- Index