- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

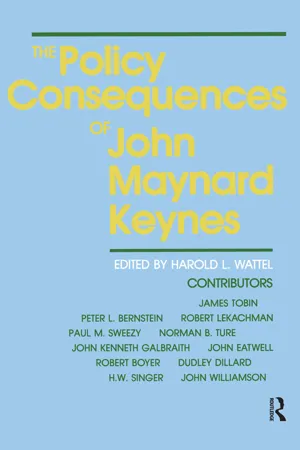

The Policy Consequences of John Maynard Keynes

About this book

Examines the history, contemporary practice, and policy issues of non-union employee representation in the USA and Canada. The text encompasses many organizational devices that are organized for the purposes of representing employees on a range of production, quality, and employment issues.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Policy Consequences of John Maynard Keynes by Wattel,Harold L. Wattel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Keynes’s Policies in Theory and Practice

The hundredth anniversary of the birth of John Maynard Keynes occurs, like the publication of The General Theory, during a world depression. History has contrived to call attention to Keynes just when his diagnoses and prescriptions are more obviously credible than at any other time since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The current depression is tragic, but the coincidence of timing may be fortunate. It should help revive the credibility of Keynesian analysis and policy within the economics profession and in the broader public arena. It may even enhance the prospects for recovery in this decade, and for stability and growth in the longer run.

Of course we have a long way to go, both to restore prosperity to the world and to restore realistic common sense to discussion and decision about economic policy. But the beginnings of recovery that have brightened the economic news this year, mainly in the United States, can be credited to Keynesian policies, however reluctant, belated, or inadvertent. Our Federal Reserve finally took mercy on the economy about a year ago and suspended its monetarist targets. Its easing of monetary policy saved the world financial system from dangerous crisis and averted further collapse of economic activity. At the same time, American fiscal measures began to exert a powerful expansionary influence on aggregate demand. This Keynesian policy was, of course, fortuitous in its timing and unintentional in its motivation. It was a combination of tax cuts, rationalized by anti-Keynesian supply-side arguments, and increased defense spending. Whatever one may think of the distributional equity and allocational efficiency of these measures, they are increasing private and public spending on goods and services and creating jobs. Every business economist and forecaster knows that, even if his boss’s speeches deplore federal deficits as the principal threat to recovery.

In the battle for the hearts and minds of economists and of the thoughtful lay public, the tide may also have turned. The devastating effects of Thatcher policies on the United Kingdom, and of Volcker policies in this country after October 1979, have opened many eyes and minds. The idea that monetary disinflation would be painless, if only the resolve of the authorities to pursue it relentlessly were clearly announced and understood, proved to be as illusory as Keynesians predicted. Monetarism—both of the older Friedman version stressing adherence to money stock targets and of the newer rational expectations variety—has been badly discredited. The stage has been set for recovery in the popularity of Keynesian diagnoses and remedies. I do not mean to imply, of course, that there is some Keynesian truth, vintage 1936 or 1961, to which economists and policymakers will or should now return, ignoring the lessons of economic events and of developments in economics itself over these last turbulent fifteen years. I do mean that in the new intellectual synthesis which I hope and expect will emerge to replace the divisive controversies and chaotic debates on macroeconomic policies, Keynesian ideas will have a prominent place.

The Postwar Record

A strong case can be made for the success of Keynesian policies. Virtually all advanced democratic capitalist societies adopted, in varying degrees, Keynesian strategies of demand management after World War II. The period, certainly until 1973, was one of unparalleled prosperity, growth, expansion of world trade, and stability. Unemployment was low, and the business cycle was tamed. The disappointments of the 1970s—inflation, stagflation, recessions and unemployment resulting from anti-inflationary policies—discredited Keynesian policies. But after all, the Vietnam inflation occurred when President Johnson rejected the advice of his Keynesian economists and refused to raise taxes to pay for his war. The recoveries of 1971–73 and 1975–79 ended in double-digit inflation in the United States. But the Yom Kippur war of 1973, OPEC, and the Ayatollah Khomeini were scarcely the endogenous consequences of those recoveries or of the monetary and fiscal policies that stimulated or accommodated them. Indeed, the main reason for pessimism about recovery today is the likelihood that excessive caution, based on misreading of or overreaction to the 1970s, will inhibit policy for recovery in the 1980s. If so, we will pay dearly in unemployment, lost production, and stagnant investment to insure against another burst of inflation.

But if we Keynesians need feel no compulsion to be apologetic, neither are we entitled to be complacent. Keynes did not provide, nor did his various followers over the years, a recipe for avoiding unstable inflation at full employment. The dilemma, though it became spectacularly severe in the last fifteen years, is an old one. It was recognized and prophesied by Keynesians like Joan Robinson and Abba Lerner in the early 1940s, when commitments to full-employment policies after the war seemed likely, and it was a practical concern of policymakers throughout the postwar period. It still remains the major problem of macroeconomic policy. Keynesians cannot accept—nor will, I think, the politics of modern democracies—the monetarist resolution of the dilemma, which amounts simply to redefining as full employment whatever unemployment rate, however high, seems necessary to ensure price stability. But we cannot ignore the possible inflationary results of gearing macroeconomic policies simply to the achievement of employment rates that seem “full” by some other criterion. The politics of modern democracies will not allow that either. I shall return to this central issue later.

Keynes on Macroeconomic Policy

It is time now to say more about what Keynesian policies are. Actually, The General Theory itself contains little in the way of concrete policy recommendations; for the most part, those are left for the reader to infer. But Keynes was, of course, an active participant in policy debates in the United Kingdom in the 1920s and 1930s. One evident purpose of The General Theory was to provide a professional analytical foundation for the policy positions he had been advocating in those debates.

Keynes opposed Britain’s return in 1925 to the 1914 parity of sterling with gold and the U.S. dollar. His arguments were summarized in The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill, who was chancellor of the exchequer at the time. More from shrewd realism than from theory, Keynes based his opposition on a view he held consistently thereafter and formally expounded in The General Theory: the downward inflexibility of money wages. He predicted, correctly in the event, that making wage costs fall to correct the overvaluation of the pound would be difficult, socially disruptive, and economically costly. He thought that workers and their unions would accept lower real wages accomplished by a lower exchange value of sterling and higher prices for imports, while they would resist the equivalent adjustment via cuts in money wages. Once the fateful decision he opposed was taken, moreover, Keynes advocated government leadership in bringing about a smooth reduction of nominal wages. This advice, too, was ignored. Britain entered a long period of industrial strife, mass unemployment, and depression.

In 1929 the Liberal party, led by Lloyd George, proposed during its unsuccessful electoral campaign a program of public works to relieve unemployment. Keynes supported the proposal in his pamphlet with H. D. Henderson, Can Lloyd George Do It? There and in his later testimony before the Macmillan Committee, Keynes refuted what came to be known as the “Treasury View.” In modern parlance, this view was that public-works outlays, financed by borrowing, would “crowd out” private borrowing, investment, and employment one hundred percent. The U.K. Treasury, like other exponents of crowding-out scenarios in other countries and at other times, made no distinction between situations of idle and fully employed resources. Keynes pointed out how public and private saving generated by public-works activity, and overseas borrowing as well, would moderate the crowding out the Treasury feared and how the Bank of England could be accommodative. Of course, only after the famous multiplier paper by Keynes’s student R. F. Kahn, stimulated by this very controversy, could Keynes develop a full rationale for his position.

The reigning governments would neither adjust the exchange rate nor adopt expansionary fiscal measures. Keynes was therefore led for macroeconomic reasons to favor a general tariff, in effect a devaluation of sterling for merchandise transactions only. When Britain was finally forced to devalue sterling in 1931, Keynes lost interest in the tariff, though one was enacted anyway. Keynes was, of course, quite aware of the “beggar-my-neighbor” aspects of devaluations and tariffs, but in the British policy discussions he was a Briton. The General Theory, fortunately, is cast in a closed economy, interpretable as the whole world, and thus excludes nationalistic solutions.

The general characteristics of Keynes’s policy interventions are clear from these examples. Keynes consistently focused on real economic outcomes, to which he subordinated nominal and financial variables, prices, interest rates, and exchange rates. He naturally and unproblematically attributed to governments the power and the responsibility to improve macroeconomic performance. Keynes was a pragmatic problem solver, always ready to figure out what to do in the circumstances of the time. These characteristics carried through to his policy career after The General Theory, his effective contributions to British war finance and international monetary architecture.

What does The General Theory itself say about policy? Fiscal policy, long regarded as the main Keynesian instrument, is introduced obliquely as a means of beefing up a weak national propensity to spend. Keynes warns against budget surpluses built by overly prudent sinking funds. He advocates redistribution through the fisc in favor of poorer citizens with higher propensities to consume. He welcomes public investment but deplores the political fact that business opposition to productive public investments limits their scope; nonetheless, intrinsically useless projects will enrich society if the resources directly and indirectly employed would otherwise be idle. Keynesian theory of fiscal policy was developed by others, notably Alvin Hansen and the members of his Harvard Fiscal Policy Seminar.

The Role of Money

Keynes was ambivalent on monetary policy. For fifteen or twenty years following publication of The General Theory, many economists, more in England than America, used the authority of the book to dismiss or downgrade the macroeconomic importance of money. Their reasons were first, the apparent insensitivity of investment and saving to interest rates during the 1930s, and second, the observed insensitivity of interest rates to money supplies in the same period. Keynes’s own views were more subtle. Though he originated the “liquidity trap” and exploited it in his theoretical attack on the “classical” theory of unemployment, in his discussions of monetary policy he did not regard it as a typical circumstance or as an excuse for inaction by central banks. Neither did he regard investment decisions as beyond the reach of interest rates. His skepticism arose from his belief that the long-run expectations governing the marginal efficiency of capital are so volatile and unsystematic that central banks might well be unable to offset them by varying interest rates. Yet he thought they should try, arguing for example that mature investment booms should be prolonged by reductions in interest rates, not killed by monetary tightening.

The same view led Keynes in The General Theory to advocate some “socialization” of investment. This idea is not spelled out. Apparently Keynes had in mind not only public capital formation and tax policies affecting private investment, but more comprehensive, though cooperative, interventions in private investment decisions. Moreover, he had in mind not only cyclical stabilization but a long-run push to saturate the economy with capital and accomplish “the euthanasia of the rentier.” Perhaps Jean Monnet’s postwar “indicative planning” in France, where government sponsored a coordinated raising of sights to overcome pessimism and lift investment, is an example of what Keynes had in mind. Perhaps some of the Swedish measures designed to make investment less procyclical are another example.

Finally, I want to call attention to Keynes’s habit of regarding wage determination as subject to “policy.” This is evident in The General Theory as well as in the pamphleteering cited above. In the book, Keynes discusses stable versus flexible money wages as an issue open to social choice. He regards cyclical stability of nominal wages not only as likely but as preferable to flexibility. In a famous passage, he notes that monetary expansion and wage reduction are equivalent ways of attaining higher employment and observes that only “foolish” and “inexperienced” persons would prefer the latter to the former. His frequent references to “wage policy” do not fit very well with his attempt at the outset of The General Theory to build his story of involuntary unemployment on the competitive foundations of Marshallian economics. But in policy matters Keynes was a shrewd and practical observer, and it would not be farfetched to infer from his hints that he expected and advocated direct government interventions in the wage-setting process.

Keynesian Principles of Macroeconomic Policy

The theory of macroeconomic policy, the subject of bitter controversy today, really developed after World War II and after Keynes’s death. The principles of what came to be known as Keynesian policies were expounded in the postwar “neoclassical synthesis” by Paul Samuelson and others. They occupied the mainstream of economics until the powerful monetarist and new classical counterrevolutions of the last fifteen years. They were the intellectual foundations of official U.S. policies in the Kennedy-Johnson years, when the media discovered them and somewhat misleadingly called them the “New Economics.” They are expounded in the 1962 Economic Report of the Kennedy Council of Economic Advisers.

Let me review those principles, with particular reference to the items that are now particularly controversial, some of which are explicitly rejected by U.S. policymakers, as well as by those of other countries, notably the Thatcher government.

The first principle, obviously and unambiguously Keynesian, is the explicit dedication of macroeconomic policy instruments to real economic goals, in particular full employment and real growth of national output. This has never meant, in theory or in practice, that nominal outcomes, especially price inflation, were to be ignored. In the early 1960s, for example, the targets for unemployment and real GNP were chosen with cautious respect for the inflation risks. Today, however, a popular anti-Keynesian view is that macroeconomic policies can and should be aimed solely at nominal targets, for prices and/or nominal GNP, letting private “markets” determine the consequences for real economic variables.

Second, Keynesian demand management is activist, responsive to the actually observed state of the economy and to projections of its paths under various policy alternatives. The anti-Keynesian counterrevolutionaries scorn activist macroeconomic management as “fine-tuning” and “stop-go” and allege that it is destabilizing. The disagreement refers partly to the sources of destabilizing shocks. Keynesians believe, as did Keynes himself, that such shocks are endemic and epidemic in market capitalism; that government policymakers, observing the shocks and their effects, can partially but significantly offset them; and that the expectations induced by successful demand management will themselves be stabilizing. (Of course, Keynesians have by no means relied entirely on discretionary responsive policies; they have also tried to design and build automatic stabilizers into the fiscal and financial systems.) The opponents believe that government itself is the chief source of destabilizing shocks to an otherwise stable system; that neither the wisdom nor the intentions of policymakers can be trusted; and the stability of policies mandated by nondiscretionary rules, blind to actual events and forecasts, are the best we can do. When this stance is combined with concentration on nominal outcomes, the results of recent experience in Thatcher’s Britain and Volcker’s America are not hard to understand.

Third, Keynesians have wished to put both fiscal and monetary policies in consistent and coordinated harness in the pursuit of macroeconomic objectives. Any residual skepticism about the relevance and effectiveness of monetary policy vanished early in the postwar era, certainly in the United States though less so in Britain. Keynesians have, of course, opposed the use of macroeconomically irrelevant norms like budget balance as guides to policy. They have, however, pointed out that monetary and fiscal instruments in combination provide sufficient degrees of freedom to pursue demand-management objectives in combination with whatever priorities a democratic society chooses for other objectives. For example, Keynesian stabilization policies can be carried out with large or small government sectors, progressive or regressive tax and transfer structures, and high or low investment and saving as fractions of full-employment GNP. In these respects, latter-day Keynesians have been more optimistic than the author of The General Theory: they believe that measures to create jobs do not have to be wasteful and need not focus exclusively on bolstering the national propensity to consume. The idea that the fiscal-monetary mix can be chosen to accelerate national capital formation, if that is a national priority, is a contribution of the so-called neoclassical synthesis. Disregard of the idea since 1980 is the source of many of the current problems of U.S. macroeconomic policy, which may not only be inadequate to promote recovery but also perversely designed to inhibit national investment at a time when greater provision for the future is a widely shared social priority.

Fourth, as I observed earlier, Keynesians have not been optimistic that fiscal and monetary policies of demand management are sufficient to achieve both real and nominal goals, to obtain simultaneously both full employment and stability of prices or inflation rates. Neither are Keynesians prepared, as monetarist and new classical economists and policymakers often appear to be, to resolve the dilemma tautologically by calling “full employment” whatever unemployment rate results from policies that stabilize prices.

Every American administration from Kennedy to Carter, possibly excepting Ford, has felt the need to have some kind of wage-price policy. This old dilemma remains the greatest challenge; Keynesian economists differ among themselves, as well as with those of different macroeconomic persuasions, on how to resolve it. It may be ironically true that, thanks to good luck and to the severity of the depression—the two Eisenhower-Martin recessions of the late 1950s helped pave the way for an inflation-free Keynesian recovery in the early 1960s, and the Volcker depression may do the same—revival of inflation is unlikely during recovery in the 1980s, just when policymakers are acutely afraid of it. But it would be foolish to count on that, even more to assume the problem has permanently disappeared.

The Need for Incomes Policy

The need for a third category of policy instruments—in addition to fiscal and monetary, the “wage policy” hinted in The General Theory—is clear to me. We can and should push other measures to reduce the expected value of the NAIRU (the nonaccelerating-inflation rate of unemployment). These include standard labor market, manpower, and human capital policies. They include attacks on the legislative sacred cows t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. Keynes’s Policies in Theory and Practice

- 2. Wall Street’s View of Keynes and Keynes’s View of Wall Street

- 3. The Radical Keynes

- 4. Listen Keynesians!

- 5. Keynes’s Influence on Public Policy: A Conservative’s View

- 6. Keynes, Roosevelt, and the Complementary Revolutions

- 7. Keynes, Keynesians, and British Economic Policy

- 8. The Influence of Keynes on French Economic Policy: Past and Present

- 9. The Influence of Keynesian Thought on German Economic Policy

- 10. Relevance of Keynes for Developing Countries

- 11. Keynes and the Postwar International Economic Order

- About the Contributors