![]()

Part 1

Change and Continuity in Social Cognition

Cross-Species Aspects of Social Cognition and Behavior

![]()

1

Prosocial Behavior and Interindividual Recognition in Ants

From Aggressive Colony Defense to Rescue Behavior

Elise Nowbahari, Alain Lenoir, and Karen L. Hollis

Introduction

Ants, like many other eusocial insects—for example, honeybees, bumblebees, and termites—dominate their environment and adapt their behavior to it. Hölldobler and Wilson (2009) suggest that ants make up around 10% of extant insects worldwide and that ant colonies have been dominant elements of land habitats for at least 100 million years. The main reason for their ecological success is their sophisticated social organization, which is based on cooperation between members of two basic castes, namely a small reproductive caste and a much larger worker caste. The core of this social organization is reciprocal cooperative communication. A number of studies of social insects’ behavior in different cooperative situations has shed light on the cognitive abilities required to accomplish these different tasks. However, prosocial behavior is often overlooked.

Prosocial behavior is defined as all social actions that benefit other members of the social group (Decety and Svetlova, 2012) and has been investigated mainly in humans and other primates. Prosocial behavior includes altruistic behavior, which imposes the additional criterion that the behavior benefits the recipient but at a cost to the donor1. Altruistic behavior, at first glance, would seem to defy Darwinian natural selection because it does not appear to benefit individual gene propagation. However, this evolutionary paradox is easily explained in terms of three principal theories: (1) The kin selection theory of Hamilton (1964) posits that the donors of altruistic acts obtain an indirect benefit whenever their behavior benefits close relatives, which of course are likely to share the donors’ genes. Kin selection requires individuals to be able to recognize kin and non-kin. (2) Trivers’ (1971) theory of reciprocal altruism posits that non-related individuals obtain a delayed benefit from performing altruistic acts if the social structure requires reciprocity. Reciprocal altruism requires individuals not only to recognize individuals but also to possess some form of scorekeeping memory mechanism that reduces the likelihood of cheating. Finally, (3) Zahavi’s (1995) prestige hypothesis suggests that helping behavior is an honest signal, albeit a costly signal, of social prestige, a signal that is easily perceived by group members and that improves mating access or dominance status. Although Zahavi presented his prestige hypothesis as an alternative to kin selection, Lotem, Wagner and Balshine-Earn (1999) suggest that both theories may work together, with helping behavior evolving signals of individual quality. In short, then—and whether altruism derives from kin selection, reciprocal altruism or the search for prestige—it is an adaptive form of behavior and, thus, like other behavioral adaptations, is favored by natural selection.

Prosocial behavior exists in various forms and many taxa, from bacteria to primates. Recently, “altruistic-like” behavior has been demonstrated in bacteria. Many examples of antibiotic resistance, for example nosocomial (i.e., hospital-acquired) infections, have been known for many years but their mechanisms are not fully understood. However, in colibacillos infections with Escherichia coli, recent research has demonstrated that this resistance to antibiotics comes from a few (1%) very resistant bacteria that protect others by producing a molecule that makes them insensitive to the antibiotic. Because these super-resistant bacteria reproduce less quickly than others, their reaction to antibiotics constitutes a form of altruistic behavior that benefits individuals of the same clone at their own expense (Lee et al., 2010). Yeasts, too, also exhibit what might be called cooperation. For example, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast, cells express a gene called FLO1 that triggers flocculation, a form of protection against stressors such as antibiotics or alcohol. These genes aggregate preferentially independently of the rest of the genome (Smukalla et al., 2008).

Eusocial ants, for example, demonstrate many different types of cooperation, including parental helping, reciprocal help, and a division of labor in which different groups of individuals specialize in particular tasks necessary to the colony as a whole. Prosocial behavior in ants also includes rescue behavior, an extreme form of altruistic behavior in which not only do ants place themselves in a risky situation to help a victim in a distress, but the rescuer is not rewarded and receives no benefit, except of course, the benefit that accrues from kin selection and reciprocal altruism (Nowbahari and Hollis, 2010). Yet another example of prosocial behavior in ants is aggressive colony defense, in which an ant places itself in a risky situation to protect its colony against intruders. These two latter forms of altruistic behavior, rescue and colony defense, display the remarkable cognitive capacities of ants—the capacity to distinguish nestmates from foreigners, the capacity to learn to recognize individual foragers, and the capacity to adapt their behavior accordingly.

In this chapter we focus on this ability of ants to adapt their behavior to these two very different social interactions. That is, in one of these types of social interactions, ants encounter potential intruders, and in the other they encounter distressed nestmates. Thus, in each encounter, an ant is in a specific situation that might be viewed as a decision point resulting in a series of behavioral patterns that demonstrate their sophisticated capacity for social recognition. The complexity and precision of these behavioral sequences are context-dependent and demonstrate the tendency of ants to accomplish a precise goal: either to scare off and eliminate the intruder or to release the nestmate from entrapment. We will show that these prosocial aptitudes are based on social cognition, which not only depends on phylogenetic membership but also changes during individual development (ontogenesis). We also present results demonstrating that chemical compounds are involved in these two situations, which act as signals to elicit the appropriate behavior.

Prosociality and Social Recognition

Social recognition is the basis of all social behavior and, from an evolutionary perspective, has fitness consequences for both the individual that performs the behavior and the recipient. The ability to discriminate between nestmates and foreigners has been observed in a large number of social hymenopteran species and particularly in ants (Breed and Bennett, 1987; Vander Meer and Morel, 1998; Lenoir et al., 1999; Breed et al., 2004). The underlying mechanisms of this discriminative ability have been the object of much study. More than 90% of the signals used in these types of social communication by ants are chemical (e.g., Hölldobler and Wilson, 2009; d’Ettorre and Lenoir, 2010; Van Zweden and d’Ettorre 2010; Sturgis and Gordon, 2012). However, other signals, such as visual signals, sound and touch, also are used by many species in communication, but ordinarily just to amplify the effects of pheromones. Some signals are complex, combining smell, taste, vibration (sound) and touch. Notable examples are the waggle dance of honeybees, the recruitment trails of fire ants, and multimodal communication in weaver ants. To this list we can easily add colony defense and rescue behaviors in ants.

In the last four decades many studies have addressed the nature and location of production of the communication signals perceived by ants and other social insects (e.g., Bagnères and Morgan, 1991; Soroker et al., 1994; Sherman et al., 1997; Starks, 2004; Bos et al., 2010; Bos and d’Ettorre, 2012). Today, researchers acknowledge that ants and other social insects rely on chemical signals, particularly cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs), which are a blend of long chain hydrocarbons present on the cuticle of each individual; because these CHCs are transferred from one or more of the several glands located in various parts of the ant’s body, they constitute a signature mixture (Wyatt, 2010). Thus, ants are able to discriminate nestmates from non-nestmates using olfactory cues or contact chemoreception. Nestmates differ from non-nestmates by chemical cues produced by the individuals, which have a genetic basis, or in cues that are acquired from the environment, especially from their food (e.g., Crozier, 1987; Crosland, 1989a,b; Sorvari et al., 2008). This signature mixture serves as a template for comparing the encountered label with the internal representation of colony odor and hence determination of colonial membership; worker ants learn to recognize these cues early in adult life (Lenoir et al., 1999). Below we show how recognition of this colony label, in combination with additional chemical cues, or pheromones, that may be released from the same glands responsible for ants’ CHCs, can evoke a variety of different responses, including aggressive colony defense, alarm or assembly response, recruitment, and rescue behavior.

Prosociality, Aggressive Behavior and Closure of Societies

Ants, like many social insects, normally attack conspecific intruders vigorously, even when intruders belong to the same species, which implies an accurate system of recognition. Colony existence often depends on the capacity of the colony to defend the nest, territory, and food sources against intruders (Stuart, 1988); indeed, colony defense maintains colony insularity against competitors and has played an important role in the evolution of eusociality (Wilson and Hölldobler, 2005). As Hermann and Blum (1981) reported, ants use a wide range of defensive mechanisms, including collective strategies and individual patterns of behavior. These behavior patterns, collectively called agonistic behavior (sensu De Vroey and Pasteels, 1978), appear to be distinctly aggressive (e.g., biting and stinging) and nonaggressive (e.g., escape and defensive immobility).

The animal behavior literature is full of examples of agonistic behavior in social interactions, especially predation and competition. Although at first glance agonistic behavior may not appear to be prosocial behavior, as a means of colony defense, it not only is a form of social cooperation, but also might be considered an especially extreme form of altruistic behavior because the defending individual places itself at great risk of injury while gaining no immediate benefit for itself. Nonetheless, because ant colonies typically consist of related individuals, defenders receive an ultimate benefit via kin selection. Nestmate recognition acts as a proxy for kin recognition (Lenoir et al., 1999), allowing for social cohesion and protection of colony resources from competitors and parasites.

An example of the precision of non-nestmate recognition is shown in Figure 1.1, which shows the results of an experiment examining the diversity of aggressive reactions of resident ants toward a variety of intruder ants obtained from different colonies. The experiment was conducted with Cataglyphis cursor, a Mediterranean desert ant, whose colony size varies between 50 and 1600 individuals. The colony represents a monogynous society, meaning that it contains a single queen; moreover, C. cursor colonies are parthenogenetic, meaning that some individuals are asexually reproduced. Thus, not only are all individuals related to one another via a single mother, the queen, but also some individuals—those produced via asexual reproduction—are genetically identical. These monogynous and parthenogenetic characteristics of the colony would be expected to play a critical role in nestmate vs. non-nestmate recognition.

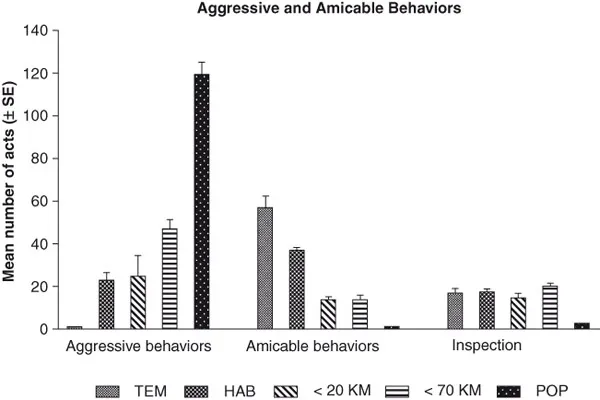

FIGURE 1.1 Mean number (± SE) of aggressive and “amicable” acts exhibited during a 15-min observation period by Cataglyphis cursor ants toward either a nestmate control (TEM) or a stranger ant from different habitats. HAB: Same habitat; < 20 Km: Within 20 Km; > 70 Km: Habitat greater than 70 Km; POP: Habitat on opposite side of Rhone River.

Each C. cursor colony was tested with four different kinds of stranger colonies: (a) the colony’s close neighbors from the same habitat; (b) colonies from a different habitat less than 20 Km away; (c) colonies from an area more than 70 Km away; or, (d) colonies collected in an area more than 70 Km away and separated by a natural barrier, namely the Rhone River. Because it cannot be crossed by ants, the Rhone essentially splits the ant population, producing two separate populations.

For each test an individually marked stranger ant was introduced in the foraging area of the resident colony. Then, during a 15-min observation period, all interactions with this stranger, in the foraging area or inside the nest, were recorded. Lastly, 72 hours later the colony was inspected to determine whether the stranger ant was adopted or rejected.

The results show a clear link between levels of aggression, recognition and geographical distance from the test colony and the possibility of adoption. Aggressive behavior was more intense when it was directed toward ants that came from geographically distant colonies and less intense when it was directed toward intruders from colonies of the same habitat (Figure 1.1). Concerning the adoption or rejection of foreign ants, when intruders originated from colonies within the same habitat, approximately 64% of ants were adopted. This result was not surprising because the colony reproduces by fission, meaning that a new colony is formed by a group of emigrant workers from the original colony together with another emigrant that has the potential to become their new queen (Lenoir et al., 1990); thus, colonies within the same habitat are likely to be relatives. When, however, intruders were from colonies in a different habitat, the adoption rate was significantly less, namely 42% (<20 Km) and 38% (>70 Km), respectively. Finally, in the case of very distant colonies separated from one another by the Rhone River, considered as two populations, intruders were vigorously attacked and killed (Nowbahari and Lenoir, 1984).

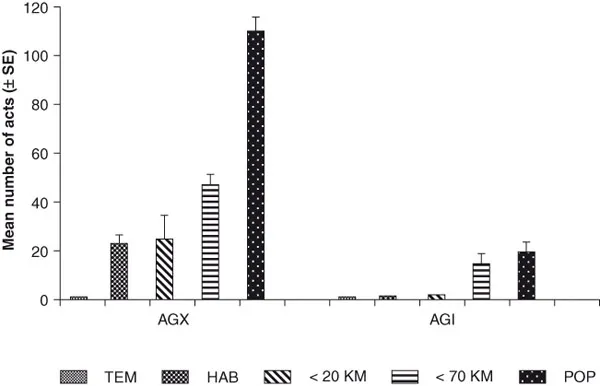

A detailed analysis of the different aggressive or defensive agonistic reactions elicited by intruders either inside the nest or in the foraging area clearly shows that the social environment has an important influence on the ability of ants to discriminate between nestmate and stranger cues (Figure 1.2). Inside the nest, the presence of so many nestmates leads to a decrease in recognized odors and, thus, strangers are subject to less aggressive reactions particularly when they come from neighboring colonies in the same habitat. A comparison of CHCs obtained from ants found in different locations and quantified using gas chromatography verified that the ant populations have different hydrocarbon profiles on each side of the Rhone River; indeed, at least two subspecies have been identified (Nowbahari et al., 1990). Finally, further CHC analysis also shows that colony recognition, as indicated by aggressive behavior and adoption of a foreign ant, is highly correlated with CHC composition (Nowbahari et al., 1990).

FIGURE 1.2 Mean number (± SE) of aggressive acts exhibited during a 15-min observation period by Cataglyphis ants toward either a nestmate control (TEM) or a stranger ant from different habitats either outside the nest (AGX) or inside the nest (AGI). HAB: Same habitat; < 20 Km: Within 20 Km; > 70 Km: Habitat greater than 70 Km; POP: Habitat on opposite side of Rhone River.

Aggressive Behavior: Factors Influencing Inter individual Variation in Behavior

Many studies have shown especially striking variation between individuals’ activity levels in both ant colonies and in bee hives (De Vroey and Pasteels, 1978; Bree...