- 290 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The results of the quality revolution have been mixed. Global competition has elevated the most successful companies, in terms of providing goods and services, but even then initiatives such as total quality, business process re-engineering and Six Sigma have been heralded as the solution, only to have been replaced with the next 'big thing' when it came along. Hoshin Kanri is not the next big thing in quality, it is a strategic approach to continuous improvement that provides a context for all of the individual elements such as Six Sigma or Lean Manufacturing. David Hutchins' Hoshin Kanri shows you how to develop a dynamic vision for continuous improvement; to implement effective policies to support it; to link key performance indicators to Six Sigma, Lean Manufacturing and Kaizen and to sustain a strategy-led programme for improving business performance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hoshin Kanri by David Hutchins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Hoshin Kanri – An Overview

In the 1950s the American Management Guru, Peter Drucker, suggested that in order to be successful in business it is necessary to be better than all of your competitors for at least something that will be important to the customer. There must be some specific reason why they would choose to buy from you rather than buy from a competitor, even if on average the competitor can outperform you.

If for example your organisation scores more points in total for Quality, Price and Delivery, but a competitor can out score you on one of them, say Quality, then that supplier will win when the customer is mostly concerned with that issue. If another has a reputation for being better on price then he will win in a price competitive market irrespective of your abilities on the other two criteria.

It is not only important to actually be the best, it is even more important to be ‘perceived’ as being the best. Perceptions and reality are often very different. Many organisations fail because they do not understand this important fact. They may know what they are good and bad at doing but the customer may well see things very differently. Even if the customer is mistaken it will still be their prerogative to choose.

In a fiercely competitive global market, the pressure is on to attempt to be the best across the broadest possible spectrum of customer-sensitive features. This raises several questions. What, for example, does ‘best’ mean? Again it is the customer’s perception of what is meant by by ‘best’ that is important, not the vendor’s. Their perception of our performance may be very different from our own and this difference might well cost us our business in a competitive market. For example, a large Middle Eastern steel company was perceived by its local customer, a large automobile company, to produce rolls of steel strip to a lower quality of surface finish than that achieved by foreign competitors. When this perception became known to the steel producer an investigation showed that there was no discernible difference. However, because they were local and because both they and the customer were located in a dry arid desert, there was no need to protect the steel reels during transportation. On the other hand, the steel produced by the competitor was wrapped in oiled paper to protect it from the corrosive salt air during a long sea journey. The oiled paper gave the impression of superior quality when, in fact, there was no difference. Had the study not been carried out, the producer might well have engaged in an expensive improvement process which might not have changed the perception unless this had also included wrapping the steel in oiled paper, which was the root of the false impression.

When demand exceeds supply and the vendor can sell everything they can make, it is possibly difficult to convince them of the importance of this philosophy. The customer will have to buy their product regardless of the quality of the service, the price, delivery or after-sales support. This will usually be the case in monopolistic situations where the customer has no choice. There is therefore no pressure on the supplier to achieve anything because they know that they are secure.

Alternatively, when supply exceeds demand, the rules change completely. Suddenly the customer becomes king and collectively has the power of life or death over the hapless vendor.

Since in this situation, every competing vendor wants to be amongst the survivors, the pressure is on to be amongst those who are favoured by the customers and in the end it will only be the best who will survive.

Hoshin Kanri is the only proven means by which this can be achieved when competition is at its most severe. It is a systematic approach that can be ruthlessly applied to grind down even the most severe competition.

Toyota have persistently applied Hoshin Kanri-style management for several decades. They have never wavered in this. In the 1950s, they were well behind most of the world’s leading automotive producers but, year by year, one by one, they moved through the pack passing one competitor after the other until in the end, in 2007, they outstripped the giant General Motors to become the world’s leading automobile producer. For years both Ford and GM attempted to stop their advance but they were unable to do so for no other reason than they did not fully understand Hoshin Kanri, Japanese Total Quality Management (TQM), (they did attempt the American version) and now they are fighting for survival with huge losses reported on the Internet.

Japanese Total Quality Management (TQM) is founded on the principles that each individual in an organisation is recognised as being the expert in their own job, that humans seek recognition and want to be involved and are motivated by a desire to be recognised as a contributor to the success of the community to which they belong. The overall objective of this form of TQM is to attempt to create an organisation (which includes the entire supply chain) in which the collective thinking power and job knowledge of all of these individuals is galvanised into a programme in which everyone is working both individually and collectively to work towards making their organisation the best in its field, both in fact and in the eyes of its customers, and all other interested parties.

It involves both voluntary and mandated team-based activities systematically carried out on a project-by-project basis at all levels of organisation to continually improve business performance in all of its aspects both on an inter- and intra-functional basis.

There are many Western interpretations of this but they are mostly focused on the creation of ‘systems’ and not the human aspects. As a result they often become policing style regimes parallel to the production processes rather than an integral part of them.

Organisations that have applied Hoshin Kanri have in some cases come from being also rans in their field to becoming performance record breakers in only a matter of 3 to 4 years. Hoshin Kanri is not a difficult concept to understand or to apply. Most organisations will have some of its elements in place and in some cases a large percentage. However, Hoshin Kanri does require meticulous planning, targeted benchmarking and the effective and systematic use of the tools for continuous improvement at all levels of the workforce. In short it is a means of managing a business.

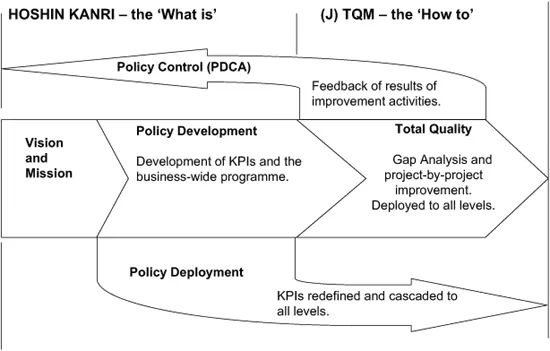

Hoshin Kanri is a Japanese management term which has no direct equivalent in the English language. The term roughly embraces four key elements of business management namely: Vision, Policy Development, Policy Deployment and Policy Control. It is also directly linked to a fifth, which is TQM, which is the means by which the Goals, which have been determined in the Hoshin Kanri process, are achieved.

Figure 1.1 gives an outline of the elements of Hoshin Kanri.

1. The Goals, aims and future scope of the organisation are derived from the Vision.

2. It requires the development of Strategy, Policy, Benchmarking and Targets.

3. The deployment of the Targets must be to all levels through a cascade process and the creation of policy at each level of management.

4. There must be a feedback loop of results to complete the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) Cycle which is the Shewhart Cycle (which some nowadays refer to as the Deming Wheel).

Figure 1.1 The four key elements of Hoshin Kanri

5. It has no value unless it also includes TQM (the Japanese version not the suspect version that fluttered for a while in the West in the late 1980s) which is not part of Hoshin Kanri but represents the Do part of the PDCA Cycle.

Hoshin Kanri and Japanese-style TQM are intrinsically related to each other. In fact, the Japanese would say that Hoshin Kanri represents the ‘what it is that we want to achieve’ and TQM (often referred to as Total Quality Control or TQC) is the means by which to close the gap between Current Performance and target performance. Japanese TQC/M includes everything that is to be found in Six Sigma, Lean Manufacturing, Total Productive Maintenance (TPM), Quality Function Deployment (QFD) and Quality Circles and all other quality-related sciences and disciplines. It would be nice to be able to include an in-depth treatment of all of these in this book but unfortunately it would then extend to several volumes. The intention has been to provide a solid base on all the key concepts and to encourage organisations to acquire ever greater expertise in each of the disciplines. As Professor Ishikawa said on many occasions, ‘Quality begins and ends with education.’

The term Hoshin Kanri has four components:

1. Ho – means Direction.

2. Shin – refers to Focus.

3. Kan – refers to Alignment.

4. Ri – means Reason.

It can be likened to ‘a leading star’ or the way that one point of a compass always points towards the North Pole.

Perhaps more appropriate is the way that iron filings go into alignment on a piece of paper if the pole of a magnet is placed underneath. Each small iron filing could be considered to be just one employee with everyone focused towards the Vision and Aims of the organisation.

The concept is based on the principle that the most powerful organisation is the one which has managed to harness the creative-thinking power of all of its employees in order to make the organisation the best in its business. It requires that each person in an organisation be regarded as the expert at their own job and their contribution recognised. All the members of an organisation must have a clear understanding of the organisation’s Vision and Goals. With all members in perfect alignment and clearly understanding their own role in the achievement of those Goals as they are trained and encouraged to work together to achieve them, then the productive power of the organisation would be optimal.

THE CHALLENGE! – THE NEGATIVES THAT HOSHIN SEEKS TO ELIMINATE

Unfortunately most organisations are a very long way from the Hoshin ideal. In many cases, they exhibit a blame culture with recriminations and punishment when things go wrong and very little in the way of praise when they go well. Direct employees are treated as robots, nobody asks them anything or involves them in anything. They are only given the minimum training and in some cases no training at all. They are not given much information as to how the company is doing in its marketplace or even the purpose of their own jobs. Only the directly relevant negative financial Goals and financial constraints are clear. All other organisational Goals are either stated in vague or very subjective general terms and are often open to wide interpretation.

In an organisation which does not practice Hoshin Kanri or something similar, then in the absence of clearly-defined quantitative Goals, managers are somehow mysteriously expected to ‘know’ them. Usually they struggle to do so but their perceptions as to their meaning will often vary widely from person to person and across the organisation. The resulting confusion will generally lead to serious underachievement against the potential capabilities of the organisation when everything is in alignment.

Since all departmental managers will be managing in line with their own interpretations of the business Goals and Targets, there will be considerable conflict and sub-optimisation. Departmental Goals which may seem clear to the managers will be considered to be more important than organisational Goals which appear vague and indistinct. Goals for Quantity which will derive from the financial Goals and constraints will often appear to be very clear whereas Goals for Qualitative requirements will usually be stated in euphemistic terms, if at all: for example, ‘we must have better performance’ or ‘increase customer satisfaction’. On the face of it, these seem like laudable Goals but in reality they mean nothing because they are too vague. This vagueness cannot compete with the clarity of the financial Goals; as a consequence the qualitative Goals will always be the poor relation even though their sustained non-achievement could result in dramatic financial impact or even threaten the future of the operation.

This lack of clarity also leads to rivalry and conflict between departments. Managers have their own ambitions and these may not always be compatible with the Goals of the organisation as a whole or the local Goals of other departments. For example, the IT manager might have the Goal of perfect information flow. In order to achieve it, they might propose the use of some complex documentation by other departments. In order to satisfy their needs, the relevant managers might be required to spend their precious time filling in the forms required by IT when they would prefer to use it for their own needs. The consequence is that there is now a conflict between the demands of one department and the local needs of the others.

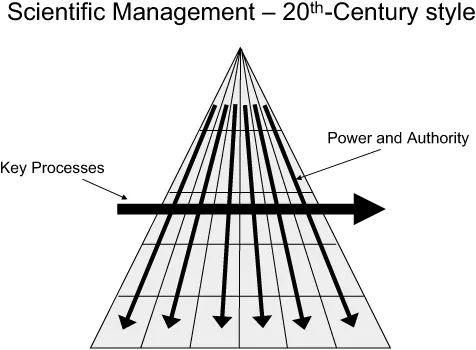

A further common problem is the lack of process ownership. For most of the 20th Century, the so-called Scientific Management System prevailed in the West and also throughout the Soviet system. In such organisations, each department was almost an independent fiefdom. In some cases, it literally bought and sold its products and services from or to the other departments within the organisation. Each of these ‘fiefdoms’ were fiercely hierarchical. Promotion, hiring and firing only occurred within the department, with the consequence that each was a self-contained unit. Whilst the organisation may have had business-wide advisory and service departments such as maintenance, training, HR, industrial engineering, and so on, they were often regarded as intruders by the managers and treated with hostility and suspicion.

As a consequence, these organisations had very strong vertical fibres of organisation but were very poor horizontally. As can be seen in Figure 1.2, processes run horizontally across departments which meant in effect that no one owned the process.

In the worst case scenario, each department performs its activities and then in effect ‘throws the output over the wall’ to the next department. There would be very little communication in either direction between the two and virtually no understanding of each other’s needs. When things inevitably and frequently went wrong, the practice for each would be to blame the other. Some managers would be more expert at the blame game than others, consequently they would appear to be the most competent and therefore the ones most likely to be promoted. Since this was how everyone was promoted, they then found themselves confronted with a better class of enemy!

The nearer they got to the top of the organisation, the tougher and more sophisticated became the competition.

At the highest levels intimidation was the main weapon. The most successful managers would eat in a separate and more luxurious restaurant, they would have large offices, deep-pile carpets, oak panelled walls, named car park locations, dress differently and never speak directly to the workforce. Such distinctions are regarded as ‘perks’ but in fact are really a form of intimidation. This method of management could be regarded as the modern equivalent of the Native American’s war paint! Companies which pride themselves in more participative styles of management scorn these distinctions and make great efforts to avoid them. Whilst the worst extremes of the autocratic approach have thankfully largely become less obvious in recent years, it is nevertheless more often than not still lurking beneath the surface and few managers are either trained or encouraged to use participative management techniques. We are therefore still faced with the worst in macho-based autocratic management, and no wonder so many executives and managers have stress disorders and heart attacks in their late 30s and 40s!

Figure 1.2 Process ownership

Whilst autocratic management methods may appear to have receded in recent years and are regarded as being ‘politically incorrect’, they are nevertheless proving to be self-sustaining and very resilient. The executives and managers who reach the top in such organisations do so because they are good at this style of management. They know how to make the method work in their favour and are not interested in experimenting with any alternative that might make their position less secure. Their belief is also strengthened by their observations of the behaviour of those beneath them. They have created a w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Hoshin Kanri – An Overview

- Chapter 2 Creating the Vision

- Chapter 3 Strategy and Tactics

- Chapter 4 Driver Policies. Becoming Fit, Fast, Lean and Hungry!

- Chapter 5 Driver Measures to KPIs

- Chapter 6 Benchmarking

- Chapter 7 Prioritising KPIs and Cost of Poor Quality

- Chapter 8 Risk Management

- Chapter 9 The Loose Brick

- Chapter 10 Hoshin Policy Deployment and Control

- Chapter 11 The Voice of the Customer

- Chapter 12 Supply Chain Management

- Chapter 13 Six Sigma

- Chapter 14 Lean Manufacturing

- Chapter 15 Process Analysis and Process Re-engineering

- Chapter 16 The Principles of Continuous Improvement

- Chapter 17 Quality Circles

- Chapter 18 Business Management Systems

- Chapter 19 Quality Function Deployment

- Chapter 20 Education

- Chapter 21 Suggestions for Performance Indicators

- Chapter 22 Implementation Plan

- Index