![]()

1

Basic Perspective Terms

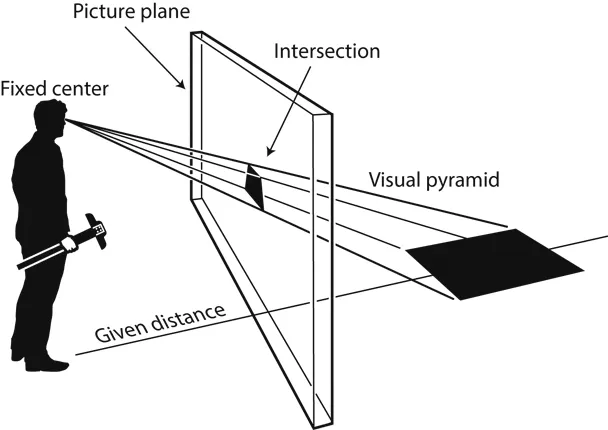

A painting is the intersection of a visual pyramid at a given distance with a fixed center.

—Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, 1435

This quote is far from the romantic verse commonly used to describe creative endeavors. Nonetheless, Alberti’s clinical delineation encapsulated a revolutionary transformation in art production: a revolution based on science. No longer did artists need to base their images on speculation and assumption, on convention and estimation. Artists could now depend on verifiable data. Art and reason became allies.

As perspective’s value became apparent, so did its deft requirements. Perspective procedures can be challenging. The alternative—drawing without perspective techniques— is merely guesswork. Perspective’s most valued asset is its ability to portray objects accurately, to assess dimensions, and to project those dimensions spatially. Perspective produces an uncompromised image, sometimes a surprising image. Drawing is often anti-intuitive, and shapes can appear different than expected. It is not a requirement to plot all images using perspective guidelines, but by practicing perspective techniques, a sense of how foreshortened shapes present themselves can be developed. Then, when the artist is sketching from observation or imagination, the skillset learned from studying perspective becomes a valuable tool to base their estimations on.

The word perspective derives from the Latin perspirere—to look through. Alberti’s definition arose from the realization that, when a sheet of glass is placed between the viewer and the world and then the view is traced, the perspective is flawless. This vision—as self-evident as it may seem—changed art production forever. Alberti’s statement is concise but his terms are abstract, so they will be examined further.

The equation consists of a viewer, a sheet of glass, and an object to be drawn. The viewer is Alberti’s “fixed center.” It is fixed because the viewer must remain stationary. A drawing cannot begin from one point of view and be finished from another, because a different location results in a different image.

Light makes the world visible. Rays of light reflect from objects and project onto the retina, converging at the viewer’s eye. This is Alberti’s “visual pyramid.” The rays “intersect” the sheet of glass (known as the picture plane). The intersection of these rays on the picture plane creates the projected image seen—a perfect representation of the world (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The intersection of the picture plane within Alberti’s “visual pyramid.”

From its inception, perspective was met with resistance. Change is difficult; artists had been creating images for hundreds of years without perspective. Painters found this new method of spatial organization difficult, confusing, and, frankly, unnecessary. But some early converts (one of the most noted being Masaccio, 1401–1428) embraced the new technology with breathtaking results. Others waited, but eventually the popularity of these new and exciting images forced those holding out to convert. The procedures were daunting. But to compete as an image maker in this new world required a new prerequisite: perspective proficiency. Alberti’s procedures will be explored further in Chapter 15.

Perspective has evolved over several hundred years to the modern approach used today, based on geometry. The only knowledge the artist requires for perspective drawing is how to read a ruler, that there are 360° in a circle, and what an isosceles triangle is (a triangle with two sides of equal length). Mastering the thirteen books of Euclid’s Elements is not required to understand perspective.

As the understanding of geometry and its relationship to perspective evolved, so did the methods. Perspective terms have also changed since 1413. For example, 600 years ago the term vanishing point did not exist, it was called a centric point. The language of perspective has evolved—as all language does—and today the term centric point has vanished. Likewise, the term distance point was once used for what is now called a measuring point (MP). Variations in terminology still exist. When perusing publications that discuss perspective, different terms may be used to describe the same thing.

Basic Terms

To begin, some basic perspective terms will be defined. These terms are used throughout the book, so it is important that their meaning and function is understood.

Station Point (SP)

The station point represents the viewer, specifically the viewer’s eye. A perspective drawing is created using only one eye. Creating a perspective drawing using a pair of eyes would result in two slightly different images. A stereographic (3-D) image is made using two station points. A single image requires a single station point. It is called a station point because it must remain stationary (the station point is Alberti’s “fixed center”).

Eye Level (EL)

The eye level is the distance from the ground to the viewer’s eye.

Horizon Line (HL)

The horizon line is the edge of the earth, where ground meets sky.

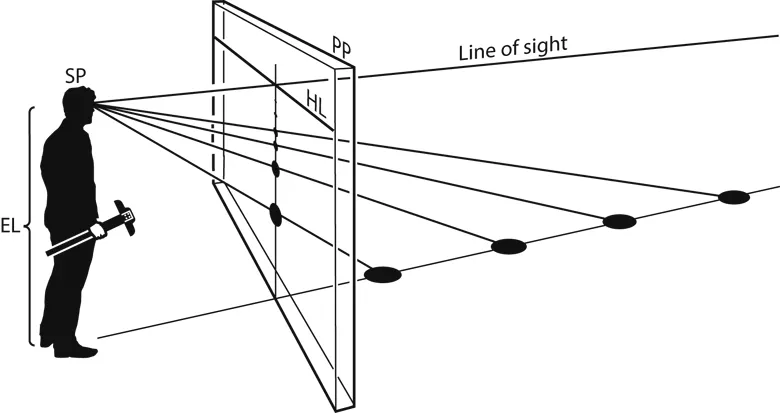

The edge of the earth is aligned with the viewer’s eye level. Whether flying in a plane or sitting on the ground, the horizon is always at eye level. Why is this? The following exercise will explain. Stand in front of a piece of glass, place a small object on the ground, and trace its position on the glass. Then place the object farther away and trace its new position. It is now higher on the glass (closer to eye level). The farther away an object is, the higher it will appear on the glass. Objects move up the glass as they move farther away. At some point, depending on its size, the object will no longer be able to be seen. Larger objects can be seen from a greater distance and are thus higher on the glass. They appear closer to eye level. If something is very large, and is very far away, it will disappear at eye level. For example, the edge of the Earth disappears at eye level, at infinity (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 As the dots move farther from the picture plane, they become closer to the eye level. Objects at infinity, like the horizon line, are depicted at eye level.

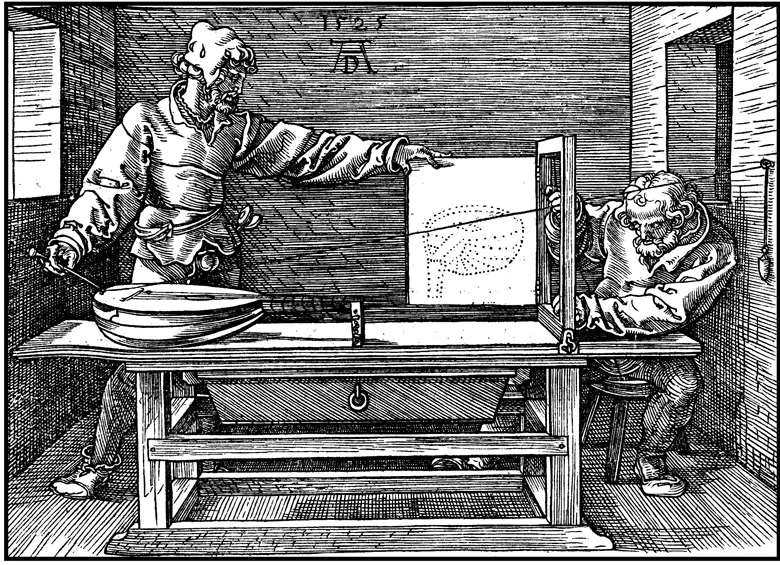

Figure 1.3 Albrecht Dürer, Underweysung, 1525. This etching shows the picture plane (the frame), the station point (the hook attached to the wall), and the visual pyramid (the string attached to the lute).

Picture Plane (PP)

The picture plane is an imaginary window positioned between the viewer and the world (Figure 1.2). It is always 90° to the line of sight (the exception being anamorphic perspective). The orientation and shape of the picture plane defines the type of perspective. If the picture plane is perpendicular to the ground, objects are in one- or two-point perspective. If the picture plane is angled to the ground, objects are in three-point perspective. In four-, five-, and six-point perspective the picture plane is curved.

Albrecht Dürer created a perspective machine that demonstrated Alberti’s theory and how the picture plane, station point, and visual pyramid function (Figure 1.3). One end of a string was attached to the wall (fixed center), and another to the object (in this example, a lute). The string represented the visual pyramid. Using movable cross hairs fixed to a frame, the intersection of the string to the picture plane was plotted. The frame represented the picture plane. When the cross hairs were in position, the string was removed. The hinged door was closed, and a dot placed where the cross hairs aligned. The door was then opened, the string was attached to a different spot on the lute and the process was begun again. This was not only tedious, but apparently a two-person job.

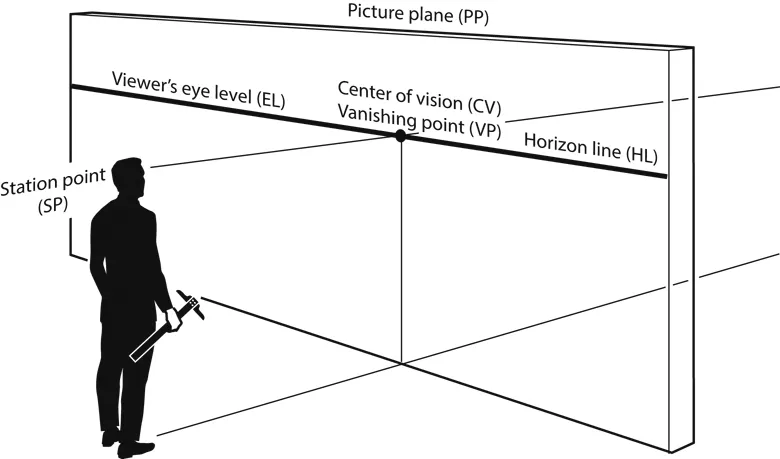

Figure 1.4 This illustration shows the relationship between the station point, picture plane, eye level, horizon line, and vanishing point.

Center of Vision (CV)

The center of vision is where the viewer is looking (also known as the focal point).

In one- and two-point perspective the line of sight is parallel with the ground plane, and the center of vision is on the horizon line. In three-point perspective the line of sight is angled to the ground plane and the center of vision is above or below the horizon line.

In day-to-day activities, a person’s focus darts from place to place as they assess their surroundings. A perspective drawing, however, is from a specific focus point...