1.1 What If Spooky Stuff Works?

One of the main goals of medicine is to improve the health of individuals. This much, it seems, is indisputable. But what exactly constitutes medicine? There are many ways to improve someone’s health. A 2012 study suggests that individuals who obtain college degrees after the age of 25 have lower risks for depression and better self-rated health (Walsemann, Bell, & Hummer, 2012). Although completing a college degree seems to be correlated with better health, it would be odd for a physician to recommend that patients enroll in a college or university to stave off mid-life depression. The reason is not the lack of a robust causal connection between education and health. For a doctor to recommend higher education as a prophylactic against depression seems professionally inappropriate.1 We want physicians to practice medicine. Just because something improves your health, it doesn’t follow that it falls within the domain of medicine.

Or does it?

The issue is not merely a question of how medicine should delimit its professional identity; for example, defining the sorts of skills a doctor should have. Where we draw the boundaries of medicine can have substantive effects on the quality of life for millions of people. Must we wait until adequate evidence from randomized clinical trials (the gold standard for experimental science) emerges before we permit public access to the treatments? Should we allocate resources to provide alternative treatments that fall outside of mainstream medicine? Should prayers be encouraged in a hospital if clinical trials show that patients’ outcomes improve after praying? Can bad science or non-science be good medicine?

Modern Western medicine prides itself on being based on science. In their essay “Engineers, Cranks, Physicians, Magicians,” published in The New England Journal of Medicine, Clark Glymour and Douglas Stalker say:

Medicine in industrialized nations is scientific medicine. The claim tacitly made by American or European physicians, and tacitly relied on by their patients, is that their palliatives and procedures have been shown by science to be effective. Although the physician’s medical practice is not itself science, it is based on science and on training that is supposed to teach physicians to apply scientific knowledge to people in a rational way.

(1983, p. 960)

Treatment protocols are not merely bits of wisdom passed from generation to generation of healers. They are grounded in a rich scientific underpinning that helps form a coherent picture of how our bodies work. A conflict between a potential therapy and well-accepted scientific beliefs automatically raises doubts about the efficacy of the therapy. If AIDS patients who were prayed for, unbeknownst to them, by faraway strangers have fewer AIDS-related diseases when compared to the control group (Sicher, Targ, Moore, & Smith, 1998), we tend to conclude that the results are clinical outliers or that there must be some unidentified naturalistic process that further investigation would discover. Not only is this a reasonable reaction in medicine, it is what any proponent of the modern scientific worldview would do when she observes something seemingly miraculous. To subscribe to a scientific understanding of the world requires at a minimum a rejection of “spooky explanations”—supernatural explanations (e.g., non-physical divine interventions) that conflict with widely accepted scientific beliefs.

Of course, defining what is “spooky” is a tricky matter. The history of science is filled with episodes where once paradoxical or spooky results eventually gain enough converts to become mainstream science. Edward Jenner’s discovery and subsequent advocacy of using cowpox to vaccinate against smallpox was met with resistance not only from the clergy on the charge that it was unnatural but also from the medical and scientific community at large. Furthermore, if we define “spooky” as something that is not explicable using the language of science alone, then we risk turning the claim that science rejects spooky explanations into the trivial truth that science rejects explanations that science rejects.

Nevertheless, if we think that medical practices from clinical to research settings ought to be grounded in science (treatment recommendations should be supported by scientific evidence, for instance), then it follows that what is not science is automatically not medicine. Indeed, a common justification for the uniqueness or privileged status of modern medicine is that it is science-based. The distinction between science and non-science thus becomes a relevant matter for medicine: to identify the boundaries of modern scientific medicine requires delineating the boundaries of science.

1.2 Verificationism: From Metaphysics to Pseudo-science

The modern discussion of where we ought to draw the line between science and non-science arguably began with the works of the logical positivists of Vienna and Berlin in the 1920s. From the start of the 20th century, Europe witnessed an explosion in scientific advances. From Albert Einstein’s remarkable theory that light behaves both as particles and as waves (1905) to Chadwick’s discovery of neutrons (1932), from Landsteiner’s identification of blood types (1900) to Fleming’s introduction of penicillin (1929), the first half of 20th century was a time of incredible scientific advances that revolutionized the way we understand the world and ourselves.

Impressed by the progress in empirical science, the positivists strived to model other intellectual endeavors (principally, philosophy) in the same mold. To do so, of course, they would need to identify what distinguishes science from other ways of understanding the world. What makes the new empirical science of the 20th century so incredibly successful? Is it possible for philosophy and other intellectual endeavors to adopt this methodology?

It is important to appreciate the historical context of the positivists. The first half of the 20th century was a tumultuous time in Europe. Along with the dazzling advances in mathematics and the empirical sciences, Europe was undergoing a series of cultural and political upheavals. The mechanical efficiency of a brutal world war driven by old-world political fissures, the devastating Spanish Influenza that killed 20–40 million people worldwide, the Great Depression, the rise of fascism, ethnic cleansings on an unfathomable scale, and a deadlier and more widespread world war culminating in the dropping of two atomic bombs—all of these highlighted the power of modern science and the grave consequences of ignorance, bigotry, and tribalism.2

From a philosophical point of view, at the turn of the 20th century, post-Kantian idealism was still the dominant school of thought in continental Europe. Like any broad philosophical movement, variations of idealism run a wide gamut; however, one of its central tenets is that we have no access to the world in and of itself. The nature of reality instead depends on how we think about it; that is, questions of ontology (what exists) and how things interact with one another can only be asked and settled relative to a particular way of conceptualizing the world. Since there is no objective reality to adjudicate between competing theories of the world, disagreements about the nature of the world become detached from objective empirical feedbacks. In other words, between two competing metaphysical views of the world (e.g., do possible objects exist?), no amount of empirical evidence could settle the disagreement. At a time when philosophy and science, especially physics, were still academically intertwined, the tremendous advances made by modern physics must have made speculative and empirically empty philosophizing of this sort less than compelling. The positivist project was first and foremost an attempt to borrow the blueprint of empirical science to rebuild the philosophical house.

The success of science, the positivists noticed, was ultimately rooted in the centrality of empirical content. Specifically, scientific statements are those that can be empirically tested or verified. To be sure, there was much disagreement in terms of what exactly constituted verification, e.g., do these statements need to be actually verified or do they only need to be verifiable in principle? What exactly does “in principle” mean? What constitutes verification? These are serious problems that forced the positivists to frequently modify their definition of empirical verifiability. Indeed, some of these nagging problems that initially seemed to be minor technical obstacles would eventually reveal devastating flaws in the positivist project. Nevertheless, defining science as rooted in empirical verification held much promise, especially against the backdrop of speculative metaphysics of the 19th century. In essence, a statement is scientific if it has empirical consequences; e.g., it entails empirical observations that can be measured, tested, confirmed, refuted, and so on.

The power of the positivist’s verificationism might seem subtle at first sight, but its epistemic implications are staggering. Take, for instance, the verifiability criterion of meaning that was favored by British positivist A.J. Ayer. The idea is that a sentence has meaning only insofar as it can be empirically confirmed or refuted. A speculative claim about the nature of reality that is immune to empirical testing is literally meaningless.3 Two theories that have the same verification processes are, according to this criterion, synonymous. Empirically empty disagreements among philosophers turned out to be no more than empty disagreements about meaningless statements. In one fell swoop, the positivists seemingly undercut much of orthodox philosophy while capturing exactly what makes modern science so special.

The positivists were certainly not the first philosophers who advocated a kind of empirical housecleaning. In section XII of his An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding, the great 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume famously suggests that, for any work, we must ask, “[D]oes it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact or existence? No. Commit it then to the flames, for it can be nothing but sophistry and illusion.” Likewise, echoing Hume’s view, Ernst Mach—another pioneer of positivist ideas—remarks that “[w]here neither confirmation nor refutation is possible, science is not concerned. Science acts and acts only in the domain of uncompleted experience” (Mach, 1988, p. 587, emphasis in original).

The emergence of empirical verification as the defining characteristic of modern science also provided philosophers with a ready tool to delineate science from pseudo-science. Although all pseudo-sciences are, by definition, not sciences, it is not true that all non-sciences are pseudo-sciences. Predicting one’s future using tarot cards is not a science in any straightforward sense, but it also does not pretend to be one. To be a pseudo-science, a discipline must attempt to be a science while failing to be so. Along with the emergence of the impressive breakthroughs in early 20th century science, there were also disciplines and theories that assumed the appearance of science without actually being science (at least according to positivists). Practices and studies like zone therapies (an early form of reflexology), phrenology (determining personalities and mental acuity by measuring the size and shape of someone’s skull), and spiritual evolution (a marriage of spiritualism and bits and pieces of Darwinian evolution) also flourished.4

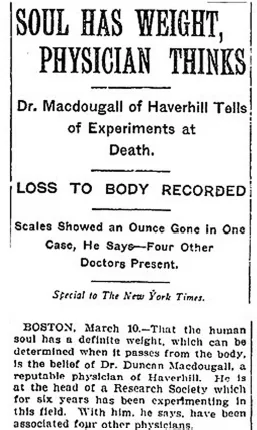

Verificationism seems like a perfect way to separate genuine sciences from the pretenders. Modern physics, for instance, makes empirical predictions. If Planck’s idea that high-energy particles come in discrete units of energy is correct, we should be able to build a device (e.g., a Geiger counter) to measure radiation that would give us discrete readings. More radiation should lead to more discrete “clicks” (as opposed to a continuum of non-discrete signals like gradually increasing volume). On the other hand, pseudo-sciences appear to lack the same level of empirical implication. When a person dies and a spiritualist posits that the soul departs the body, how are we to measure that? Do we use a scale? Do souls have weight? Souls might exist, but unless there is a way to manipulate them, measure them, and observe their effects, they are causally inert. The positivists’ verificationism tells us that, without entailing empirical observations, statements about souls are not scientific claims.