eBook - ePub

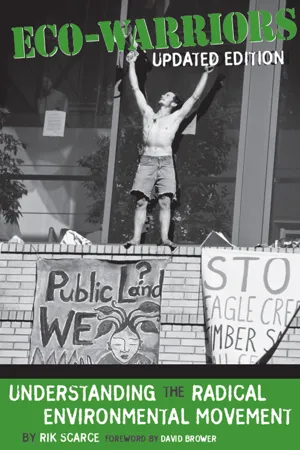

Eco-Warriors

Understanding the Radical Environmental Movement, Updated Edition

- 335 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Eco-Warriors was the first in-depth look at the people, actions, history and philosophies behind the "radical" environmental movement. Focusing on the work of Earth First!, the Sea Shepherds, Greenpeace, and the Animal Liberation Front, among others, Rik Scarce told exciting and sometimes frightening tales of front-line warriors defending an Earth they see as being in environmental peril. While continuing to study these movements as a Ph.D. student, Scarce was jailed for contempt of court for refusing to divulge his sources to prosecutors eager to thwart these groups' activities. In this updated edition, Scarce brings the trajectory of this movement up to date—including material on the Earth Liberation Front—and provides current resources for all who wish to learn more about one of the most dynamic and confrontational political movements of our time. Literate, captivating, and informative, this is also an ideal volume for classes on environmentalism, social movements, or contemporary politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Eco-Warriors by Rik Scarce in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

TOWARDS AN UNDERSTANDING

CHAPTER 1

GANDHI MEETS THE LUDDITES

Three parachutists, commandoes outfitted for cold weather combat, floated down through the February cold of central British Columbia toward a snowy, city-block square clearing. Their mission, oddly, was not to destroy but to protect; their bodies were their only weapons. The three—Myra Finkelstein, Renee Grandi, and Randy Riebin—were from Friends of the Wolf, a non-profit group established to fight the extermination of wolves wherever they are threatened. The primary aim of their sensational stunt was to draw the media’s attention by dropping into the middle of a government-sponsored wolf hunt and stopping the annual carnage dead in its tracks. Between 1982 and 1987 British Columbia had spent more than $2,400,000 to kill 800 Canis lupus, native wolves that annually killed thousands of elk, moose, and caribou, which were normally the targets of hunters. The government had organized the wolf hunt to placate angry hunters and recoup revenue lost from the drop in the hunting trade. Like the Friends, the wolf hunters also came by air. The government’s hired guns baited the wolves with mounds of caribou meat. Later, as the wolves gorged themselves or lay relaxing nearby after their feast, the hunters would return in helicopters to swoop down on them, blasting away with their 12-gauge semiautomatic shotguns, turning the ice crimson with wolf blood. Ultimately, the government hoped to wipe the Muskwa River Valley clean of wolves, effectively killing one-half of British Columbia’s wolf population.

Wolves, long portrayed in folklore as fearsome beasts, are in fact formidable predators, but ones loathe to have contact with humans. Because of ignorance about wolves’ habits, and because they and other powerful mammals—like mountain lions and grizzly bears—kill the same “game” animals to live that humans kill for sport (and attack the livestock animals that humans attempt to raise in their former habitat), wolves have been hunted relentlessly. They have been poisoned, trapped, and shot, and their habitat has been so thoroughly obliterated by human incursions that fewer than an estimated 1,300 wolves exist in the U.S., a land in which they once roamed and flourished. These highly social animals co-existed with their prey for tens of thousands of years, playing out the rituals of birth, life, death, and rebirth. In British Columbia, however, the wolves were referred to as “shop lifters,” says Finkelstein, adding, “They’d say the deer were at a devastatingly low populations and that they had to kill the wolves to compensate. But they never once talked about cutting back on the amount they were hunting. In fact, they upped the quota of native elk and stone sheep” that hunters could kill.1 Driven by outrage at the human arrogance that would extirpate wolves and break the ages-old ecological chain, Friends of the Wolf set about their dangerous, daring task.

Finkelstein and her fellow eco-warrior skydivers landed in the soft snow on that February morning in 1988, gathered their parachutes, and disappeared into the dense woods. They were prepared to stay for a week. Along with a third woman, Sue Rodriguez-Pastor, Finkelstein and Grandi had spent eighteen months preparing for the action. Rodriguez-Pastor took the entire time off from school to plan and coordinate the campaign, and the others dropped out for several quarters as the time for the hunt drew near. They each made more than thirty parachute jumps, scrounged for equipment, and raised thousands of dollars in donations—$14,000 in material and money in all. About a month before the women left for the subarctic, they enlisted the assistance of Riebin, a jump master and wilderness survival expert. Because of the cost of the operation and the need for someone intimately familiar with it to handle the crush of media interest, the women decided that one of them would not make the jump. Rodriguez-Pastor drew the short straw and assumed the role of media coordinator.

Even with Riebin there to help with the jump and the hunt sabotage, in every way the action was the women’s doing. They had met one another as students at the University of California at Davis, and as a group they became increasingly involved in environmental issues. In 1985 Finkelstein and Rodriguez-Pastor heard Paul Watson speak in Berkeley, and it was through his influence that they came to join the struggle for the wolves. Watson was a Greenpeace “mutineer” who left the organization in 1977 and founded the radical Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, a group devoted to the protection of whales, dolphins, and other marine mammals through means that have included ramming a pirate whaling ship. Watson led ambitious efforts to stop the British Columbia wolf hunt in 1984 and 1985, but he found the area of the hunt too large to cover by land alone.2 His solution was a coordinated air and ground assault by hunt saboteurs. All three of the women from Davis had served as crew members in 1987 on a Sea Shepherd vessel that successfully chased Japanese drift net fishing boats from North Pacific waters. As they talked among themselves about Watson’s plan for disrupting the wolf hunt, they became increasingly intrigued. When they announced during the drift net campaign that they would like to give it a try, Watson pledged his assistance whenever they needed it and sent them on their way.

The air assault was complemented by a group of Earth First!ers, radical wilderness advocates for whom the wolf is a totem, who intended to ski into the area as Watson had suggested. Earth First!ers had long opposed the wolf hunts, picketing British Columbia tourism offices and promoting a visitors’ boycott of B.C., an effective target since tourism is the province’s second-largest industry. John Lilburn, now an Earth First! organizer in Montana, said he had never done an Earth First! action until he and some friends read a plea by Watson for help in fighting the B.C. wolf hunt through direct action. Lilburn’s group raised $2,500 in one month and took off for Canada posing as downhill skiing enthusiasts traveling to the Calgary Olympics. Their real plans were to ski into the hunt area and occupy a lake as “a symbolic act.”3 Lilburn’s crew was unable to get to the hunt area—another group actually made it, although they did not encounter any hunters or any wolves—but they protested in front of the throngs at the Olympics. In so doing they reaped substantial publicity for their cause, as did other Earth First!ers, like those who pitched a tent in the office of the B.C. Minister of Environment, Bruce Strachan, on the opening day of Parliament and held a press conference on the spot.

The activists also had another front on which they were fighting for the wolves. During their fund raising, an unnamed individual approached the women and offered to pay up to $10,000 in legal fees if Friends of the Wolf would attempt to stop the hunt on legal grounds. He refused to give to the “direct action” campaign, saying that he was certain the suit would prove to the jaded activists that the system which they felt had consistently failed the wolves could work. Although the Americans had no legal standing to challenge the B.C. authorities in Canadian court, a Vancouver environmental group, the Western Canada Wilderness Committee (WCWC), eventually agreed to file suit. “You’ve got to use every tool that you can,” Finkelstein says, explaining the rationale the group used to accept the proposal. “We did not put much faith in the lawsuit at first, just about none. But it turned out that our case was looking better and better, and we were trying to stall until it got into court.”4

In the end, timing was everything. “If one thing had fallen apart,” acknowledges Rodriguez-Pastor, “the whole thing would have fallen through.”5 She and the others were juggling three uncertainties: precisely when the wolf hunt would be announced, when the court case would be heard, and how long their money would hold out before they would be forced to go into the wild strictly for show or quit the campaign altogether. Things worked out perfectly. On Monday, February 22, Environment Minister Strachan announced that the hunt had begun—trackers were in the forest looking for the wolves. Finkelstein and Grandi left for B.C. immediately following Strachan’s announcement; the Earth First!ers had already been there for ten days. Rodriguez-Pastor joined her comrades on the twenty-fifth. The actual killing, however, was delayed because of a warm spell that kept new snow from falling, making it impossible for the trackers to do their job since they needed fresh wolf tracks in the snow in order to follow and locate the wolves. Finally, after spending three days scouting possible locations for their jump and after spotting a freshly-baited lake and eight wolves happily devouring the easy pickings, the commandos decided to go in on February 25. Apparently, lack of fresh snow had not stopped the hunt after all. The women knew the wolves would soon be spotted and killed. As much as they wanted to delay their jump because of the lawsuit, the activists could wait no longer. Compounding their anxiety over the timing of the jump was the uncertainty of how they would get out—at the time, the group did not have the $1,000 that was needed to hire a helicopter to pluck them out following their planned week-long stay. They jumped anyway. But as soon as the media reported that the eco-warriors were on the ground, Strachan suspended the hunt to avoid a confrontation.

Press coordinator Rodriguez-Pastor was continually besieged with telephone calls from the media asking for updates. What a story! Two young women and a man trying to save hungry wolves—wolves that doubtless would eat their saviors if given half a chance, or so the press thought. In truth, there was little that Rodriguez-Pastor could tell the press. No hunters meant no action. With no hunt to disrupt, the trio in the bush, whose drop zone was near the baited lake where they spotted the wolves, spent their time hiking through the forest and warding off the canines from the hunt area. The battle looked more promising on the legal front, however. The lawsuit was filed on Friday, the day after the jump. The court denied an injunction that would have completely halted the hunt until the case could be heard in full, but it warned Strachan not to allow hunting over the weekend. The case would be heard the following Monday. It became clear that the hunt would not go on so long as the case was in court, so Rodriguez-Pastor managed to scrape together the funds to have a helicopter airlift the commandoes out of the wild. Little more than a week later, Justice Carol Huddart handed down her ruling: the permit allowing the hunt was invalid because Strachan had improperly delegated decisionmaking authority to a lower-ranking bureaucrat. Friends of the Wolf had won. The mysterious benefactor was right, on a technicality. Technicality or not, the hunt has never been resumed.

Who are the Radical Environmentalists?

The Friends of the Wolf action parallels hundreds of similar radical environmental struggles, and as such it provides clues as to what is unique about radical environmentalists. Foremost is their emphasis on confronting problems head-on through “direct action.” This often entails picketing a lawmaker’s office, the headquarters of a National Forest, or a laboratory that conducts cruel experiments on animals. It may also mean breaking the law. Some radicals use civil disobedience to get their point across, like the Earth First!ers who pitched a tent in Strachan’s office and as Friends of the Wolf were prepared to do by interfering with the hunt. Others go a step farther, destroying machinery and other property used to build roads, dig mines, harvest trees, and kill animals. It is this willingness by some to sabotage the tools of “progress” which sets radical environmentalists apart from all of their predecessors in the environmental movement.

Secondly, the point of radical environmentalists’ protests and actions is the preservation of biological diversity. A term from the science of ecology, the biological diversity of a place is, in a nutshell, its resemblance to what it looked like before people interfered with it. (Natural causes, such as massive volcanic explosions like the one on Krakatoa, may reduce biodiversity, too. Humans, however, have replaced natural causes as the primary force driving biodiversity reduction worldwide.) Biodiversity might be more properly called ecological diversity, because, as radical environmentalists use the term, it refers not only to plants and animals but to mountains, rivers, oceans as well—the non-living and living aspects of an ecosystem. Some places are not very diverse biologically or ecologically to begin with, like the regions near the polar ice caps where few animals or plants have ever lived. In other areas biodiversity is tremendous. A small section of a tropical rainforest, for example, may be home to thousands of species of insects and a multitude of other plants and animals, all of which are connected in intricate relationships that have come to be called the “web of life.”

Human interference tends to lessen this biodiversity. When a rainforest is wiped out or a city is built on former marshland, few if any of the original inhabitants remain, and the physical character of the place is permanently changed. With too much human tampering, biologically diverse places become biological wastelands. By fighting for the wolves, the Friends were emphasizing the importance of biodiversity. Without a natural range of animals, including predatory animals, biodiversity in the subarctic would suffer. If the wolves were exterminated, a semblance of biological diversity could only be maintained through artificial agents, like humans. But humans are no substitutes for wolves. When the caribou, elk, and moose migrate out of the wolves’ territory, will humans take to hunting mice, as do the wolves? Probably not.

Third, most eco-warriors act largely on their own and without direction from an organizational hierarchy. They get together in small groups, like the three women from Davis or John Lilburn’s band from Montana, to take direct action on issues of concern to them, usually environmental problems in their own backyards. At the time of the B.C. wolf hunt, Montana environmentalists were arguing for the development of a meaningful wolf reintroduction plan for Glacier National Park. The well-being of wolves in British Columbia was important for its own sake and also because success in B.C. helped to extend the wolves’ range southward into Montana, thereby restoring a level of biodiversity Big Sky country has not known for decades.

Fourth, many radical environmental activists are poor to the point of destitution. This is by choice. They possess an array of talents, and most have at least some college education. But their commitment to ending humanity’s unrelenting abuse of the Earth is what motivates eco-warriors, and they often work in low-paying jobs for the environment or work only part of the year, saving enough money to get them to the next action. Finkelstein, Grandi, and Rodriguez-Pastor, for example, came home from Canada several thousands of dollars in debt (the huge donation for the court case was exclusively for that use). Radical environmentalists also choose lifestyles that have minimal impact on the environment. Some do not own cars, many are vegetarians, and nearly all eschew occupations that directly involve environmental destruction.

A fifth distinguishing attribute of radical environmentalists is that they usually have but minimal hope of actually ending on their own the practices against which they protest. The three pro-wolf commandos knew they could stay in the wild no longer than a week and that the hunt might well go on after they left. Rather than fighting to “win” themselves, which they could not afford to do, they did what they could with the resources they had. To get the most out of their efforts, their activities were designed to draw media attention to the plight of British Columbia’s wolves in the hope that public sentiment against the hunt would increase to the point where it would be cancelled. In fact, nearly everything environmental extremists do takes place with an eye toward how it will play in the media, their strongest weapon in the fight for the Earth.

In addition, the radicals often act in ways that support the activities of more mainstream groups, such as the lawsuit filed by WCWC (although it is rare that the ties between the two are as clear as they were in British Columbia, where Friends of the Wolf gave WCWC the money it needed for the suit). In the big timber country of California, Oregon, and Washington, for instance, radical activists have repeatedly occupied redwood and Douglas fir trees after being told that a mainstream group like the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund was seeking an injunction that would stop a forest from being felled. The tree sitters’ presence, like that of the wolf activists, sometimes delays cutting until a judge can hear a request for an injunction. In other instances, the radicals offer extreme proposals for wilderness areas and the like that make those of mainstream environmental groups, such as the Sierra Club, Wilderness Society, and the National Wildlife Federation, look more reasonable. This so-called “niche theory” of environmental groups was an instrumental reason behind the formation of Earth First!. Initially, the founders adopted the role of the extremists as a tactic to allow the mainstream groups to look less radical and achieve more protection for the environment.

Some of the radicals’ characteristics are shared at least partially by the mainstream. Increasingly, biodiversity is a concern for the environmental elites, which often de...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface to the Updated Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Part One: Towards an Understanding

- Part Two: Who Would Dare?

- Part Three: Environmental Activism in Practice

- Part Four Inspiration and the Future

- Getting Involved

- Errata

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author