eBook - ePub

Project Risk Governance

Managing Uncertainty and Creating Organisational Value

- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Project Risk Governance, Dieter Fink breaks new ground in two ways. Firstly, he places project risk management in the context of today's organisations in which objectives are increasingly implemented through projects to better respond to fast-changing markets. Secondly, he applies a governance perspective to examine project risk at the project and corporate levels, an approach which is significantly under-researched and for which theoretical knowledge and professional practice are at an early stage of maturity. Project risk governance falls between corporate governance and project governance and is attracting increasing attention. The author argues that there are two reasons for this. The first is the 'projectisation' of organisations, in particular within organisations conforming to the Project-Based Organisation (PBO) model. The second is the prevalence of a strategic approach to managing risk for the purposes of protecting organisational values and creating competitive advantage. The book addresses governance, strategy, value management and building enterprise-wide Project Risk Governance (PRG) capabilities. Chapters examine the role of projects in organisations and the need to integrate project and business strategy within the framework of the Project-Based Organisation. PRG is introduced via its links with corporate and project governance and its scope is covered in chapters that identify relevant processes, structures and relationship mechanisms. Contextual influences such as the professionalisation of project management are recognised and insights provided to increase readers' understanding of uncertainty, risk events, and probabilities and of the essential requirements of managing risks at project level. The final chapter provides a roadmap to the stages and dimensions of a PRG maturity model.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Project Risk Governance by Dieter Fink in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Projects in Organisations

Introduction

The common business model is highly structured, stable and predictable. Well-defined lines of responsibility and authority exist, usually organised in a hierarchical manner. A change is occurring as projects become a major component of organisational activities. According to Bredillett et al. (2008, referenced in Aubry et al. 2010), World Bank data shows that 21 per cent of the world’s gross domestic product is tightly related to projects. To take maximum advantage of projects, vertically structured organisations are flattened so that they can respond quickly and efficiently to fast-changing market conditions. Old-style bureaucracies are increasingly being replaced by flexible, project-oriented structures.

Project- versus Product-Based Organisations

The questioning of traditional organisational arrangements has resulted in a preference for project-based approaches. This new structure is termed the project-based organisation (PBO) or multi-project organisation, and first emerged in the 1990s. For a PBO, the project is the basic form for organising its operations. It is particularly suited for entrepreneurial action and innovation since the nature of projects allows the organisation to respond quickly to an emerging market opportunity.

The key dimensions that distinguish the ‘project-based organisation’ and the ‘product-based organisation’ are business operations, technical processes and organisation structures (Du and Shi 2007). From a project management perspective, the key differences of the PBO when compared with product-based organisations are in the following two areas. First, production only occurs when the order is received and hence the project itself has to be flexible in the way it responds. For example, it may need a skillset different from previously completed projects. Second, high-level decisions have to be made as to whether or not to go ahead with the project. Projects compete with each other for funds and other resources within a portfolio of projects. To be included, the project has to contribute a net benefit to the organisation.

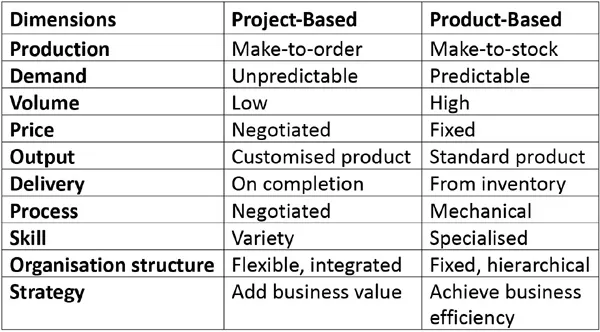

Table 1.1 highlights a number of differences that distinguish project-based from product-based organisations. In the former, projects are initiated and completed in agreement with the customer. They are made-to-order at a negotiated price and require a variety of skills, since each project is unique. The organisation structure is flexible and responsive to market needs, but concerns exist about the temporary and impermanent nature of the work. Product-based organisations, on the other hand, make stock for their inventory from which customers are supplied and charged according to a published price list. Production is largely automated and requires specialised skills. The organisation structure is hierarchical and recognises functional units and their strategic objectives.

Table 1.1 Dimensions of product-based organisations and project-based organisations

While the PBO has the advantage of flexibility, it has a number of weaknesses compared to product-based Functional Matrix Organisation (FMO). Where there are multiple and unique projects, business costs are higher since there is little scope for routine work and hence a lower average cost of production. Each project potentially presents new technological and skill challenges for which little corporate memory exists. The dynamic nature of project work consistently exposes the project team to new environments. It is easier within an FMO than within a PBO to co-ordinate resources because of the high level of production predictability and centralised control. Within a PBO projects often run quite independently and parallel with each other and may compete for the same skills and financial resources. The allocation of scarce resources across projects will have to be determined by their projected contribution to business value, a difficult task.

FMOs tend to conduct centralised activities such as research and development (R&D) that benefit the organisation as a whole. This is generally lacking within PBOs since the organisation has been flattened so that it can respond quickly and efficiently to fast-changing market conditions. More emphasis is placed on ‘eyeballing’ the market than on internal activities. In a similar way support functions such as human resource management, finance and accounting, and legal services may receive less attention within the PBO than within the FMO.

An interesting approach is to classify types of projects by their broad governance paradigms. According to Mueller (2009) three paradigms can be identified. The ‘conformist’ paradigm requires that projects strictly comply with existing processes and rules. Experienced project managers are needed to decide the processes that will deliver the most economic results, i.e. the lowest cost possible. The paradigm applies to projects that are relatively homogeneous and subjected to tight regulations, such as can be found in the construction industry.

The ‘versatile artist’ paradigm requires a balancing of a diverse set of project requirements arising from the particular needs of different stakeholders. Organisations working with heterogeneous projects, such as those applying leading-edge technology, use this paradigm. Versatile and experienced project managers are needed to manage this dynamic environment.

Under the ‘agile’ paradigm, projects have a core functionality to which features are progressively added. The project sponsor prioritises the components of the project to be developed. An example is a software development project where the core is available for immediate use and additional modules are added over time.

The Project-Based Organisation

The PBO has characteristics that require excellence in project management at both the project and corporate levels. Aubry et al. (2007: 332) referred to this as ‘a new sphere of management’ under which corporate objectives are implemented through projects if the organisation is to maximise its business value. To achieve this aim, Peltokorpi and Tsuyuki (2006) recommended that PBOs adopt project-type processes throughout the organisation. These processes follow the traditional project stages of creating, responding to, and executing business opportunities.

DEFINITIONS AND FEATURES

The terminology used to define PBOs tends to accentuate the importance of projects. Among them are the following:

• Organisational project management: transforming the organisation by adopting a strategy to manage ‘by projects’.

• Project business: the part of the business that directly or indirectly uses projects to achieve business objectives.

• Managing by projects: a corporate approach to project portfolio, programme and project management.

• Project portfolio management: managing the synergies between multiple projects, thereby adding value to the organisation.

• Temporary projects: projects are created to implement the organisation’s strategy and, once accomplished, they are superseded by new projects.

The above definitions indicate that PBOs are a relatively new phenomenon and therefore pose new challenges to management. They will have to understand the implications of becoming a PBO, and its advantages and disadvantages. New dynamism is introduced since business strategy and project management closely interact to meet challenges in the environment. Emphasis is placed on realising new values for the organisation by gaining competitive advantages (e.g. by being first to the market) and innovation (e.g. by releasing new products and services).

While most attention is focused on strategic projects, PBOs also include non-strategic projects such as compulsory projects (e.g. in banks to install ATM systems to remain on par with competitors) and project maintenance activities (e.g. to fix errors in an IT system). They mostly do such projects for themselves rather than for external customers or entities. The distinction between internal and external is in aligning corporate and project strategies. With the former, the responsibility rests within the PBO, while for the latter the responsibility is that of the client.

THE PBO AND PROJECT PORTFOLIO

Attempts to manage projects from an organisational perspective have traditionally been done via the project portfolio. What distinguishes a PBO from project portfolio management is the close alignment within a PBO between the strategy of the business and that of the projects the strategy initiates. In other words, within PBOs corporate objectives are implemented through projects. Aubry et al. (2007) refer to this as the transformation of the organisation. The business now supports a dynamic and tight interaction between business strategy and organisational structure, which is now project based.

By contrast, under project portfolio management, the value generation potential is limited to the value added to the organisation by the synergy that is created between multiple projects. Emphasis is placed on the aggregation of projects making up the portfolio and how they are planned, managed and monitored. The responsibility for the project portfolio is that of senior management who implement and maintain processes and communications relative to the aggregate portfolio. With traditional project portfolio management there is little interaction with organisational strategy.

CORPORATE AND PROJECT ACTIVITIES

Aubry et al. (2007: 330) viewed a project-oriented firm as ‘a dual set of functions: one of governance and one of operational control’. The governance perspective is reflected in the desire to align corporate and project activities to maximise business outcomes while control is exercised at the project level. Governance requires organisation-wide processes and structures to ensure that project potentials are strategically exploited. Control over projects serves to meet cost, time and quality objectives.

Tensions may emerge between corporate and project activities. Aubry et al. (2007) attribute this to friction and failure between the project and the organisation due to differences in what is expected of the project. Within PBOs there is a high expectation of gaining economic benefits from projects, which projects may subsequently fail to deliver. The solution appears to lie in managing expectations. Various options exist, including to ‘under-promise and over-deliver’, but this will increase the expectations for the next project. It may be best to ‘deliver exactly what is promised, every time’. Promises need to reflect reality as perceived by both organisational and project management.

The PBO structure supports unique and transient projects. Novel processes are followed because products made or services provided are ‘bespoke’ for the beneficiaries of the project (Turner and Keegan 2001). This is in contrast to the traditionally managed firm that works well if markets, products and technologies are slow to change. Mass production dominates because of stable customer requirements and a slowly changing environment. It can be said that the organisation works like a machine, unlike a PBO.

In PBOs, it is important to retain some central functions but they have to be linked into the project networks. They are referred to as support activities and include human resource management, information technology and systems, accounting and finance, and legal services. Projects draw on their support and services as required but do not have direct responsibility for or authority over them.

Implications of Project-Based Organisations

When considering the transformation to a PBO, a range of implications should be evaluated for their impact.

UNPREDICTABILITY

The arrival of projects is stochastic; they are difficult to predict because they arise in response to market needs. This complicates business planning with its long-term view of the environment and the opportunities it offers. Projects in a dynamic market environment cannot be planned with confidence as to their frequency and timing. This has a number of implications. For example, with the possibility of multiple projects under consideration at any one time, project managers may be expected to supervise more than one project, or it becomes increasingly difficult to always have the right level of project skills available at any one time.

PROJECT REQUIREMENTS

For project managers, the rapid growth in projects within the organisation poses resource challenges. Project managers may have to come to an arrangement with each other to share limited organisational resources. There could be competition for scarce project talent. Agreement will have to be reached as to how best to allocate employees across projects taking into consideration their skill levels and those that are required. Each project will have to make its own case to gain a share of the resources available in the organisation.

EXPECTATIONS

The role of project managers is broadened as they are now closely entwined in the operations of the business itself. They are not only expected to be effective technically in the discipline of project management but also to have the necessary aptitudes to integrate the project within broader business activities. Success of projects determines the survival and future prosperity of the organisation. Expectations are further broadened when projects extend beyond organisational boundaries. When establishing a supply chain project, for example, the needs of both supplier and customer have to be considered.

BUSINESS MODEL

The challenge for the organisation is to design a business model that best suits itself. Options range from a pure PBO to one that also includes elements of the traditional functional and/or matrix organisational structure. The decision on the best configuration is determined by the number and nature of the projects. Should the volatility of projects be large then the emphasis would be on a pure PBO structure, while the reverse would apply for projects that are infrequent and similar. The greater the number and diversity of projects, the more pronounced are the characteristics of a PBO.

Advantages of Project-Based Organisations

There are a number of advantages associated with the PBO approach to conducting business.

OPPORTUNITY

As indicated earlier, by its nature a PBO offers increased opportunities for creativity and innovation. The organisation’s products and services and project management processes are improved because of the close interaction between business strategy and project activity. Business strategy determines the changes needed to meet market needs while project management satisfies those needs through the completion of projects. Both interact to increase business value.

RESPONSIVENESS

The nature of projects allows a high degree of flexibility and responsiveness. In its simplest form, each project is a temporary endeavour to produce a unique product or service. It is a new undertaking and covers new ground. Not surprisingly, projects are staffed by professionals who are attracted by the dynamic nature of project work and exposure to different knowledge and skills. They become experienced in responding to challenges that are new to the organisation and themselves.

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

Knowledge management becomes important because of the rate at which project knowledge is created. Superficial or ineffective knowledge management causes opportunities to be missed or to be under-exploited. Project teams are encouraged to create ‘lessons learned’ reposit...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- About the Author

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 Projects in Organisations

- 2 Business and Project Interaction

- 3 Corporate and Project Governance

- 4 Project Risk Governance – Processes

- 5 Project Risk Governance – Structures and Relationships

- 6 Project Risk Governance in Context

- 7 The Concept of Project Risk

- 8 Essentials of Project Risk Management

- 9 Project Risk Governance Maturity

- Appendix 1 Survey of Key Issues in Project Risk Management

- Appendix 2 Constructing a Business Case for Project Investments

- Appendix 3 A Project Risk Governance Maturity Model

- References

- Index