![]()

Part One

Understanding Children’s Rights and Development

Part One

Some local governments have already been recognized for their committed championship of children and adolescents. But for many local authorities, becoming the guardian and promoter of children’s rights is a new, challenging and perhaps bewildering role. In many cases some basic orientation is needed for this role to take on real meaning. These preliminary chapters provide the background information and perspective necessary for this undertaking.

Chapter 1 introduces the concept and the history of children’s rights, and discusses some questions that are raised by a rights-based approach to children. A synopsis of the provisions of the Convention is followed by an account of the obligations they create, and the formal mechanisms for implementing children’s rights.

Chapter 2 provides a brief introduction to the development of children and adolescents, and discusses the contribution of both social and physical environments to this process. While acknowledging the cultural, social and economic differences in children’s lives and in the construction of their development, this chapter discusses some basic guidelines for meeting their requirements at different ages.

The Convention stresses that children’s rights are best met within the context of stable, loving families. But family stability is seriously undermined by the pressures of urban poverty. Chapter 3 discusses the kinds of support local authorities can provide to make it possible for families to fulfill their responsibilities towards their children.

![]()

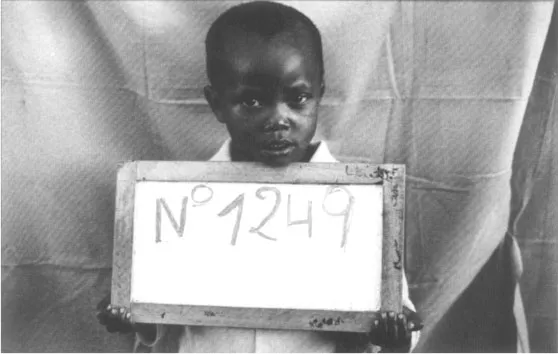

Children’s right to family and to an identity are recognized as fundamental by the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This Rwandan child is photographed as part of a family tracing programme. UNICEF 1994, Giacomo Pirozzi

1 | The Convention on the Rights of the Child |

The Convention on the Rights of the Child, the most widely accepted international treaty in the world, defines how children should be treated in the various areas of their lives. It recognizes their rights to survival, development and protection, and to an active role in matters that concern them. The breadth of the Convention’s provisions confers considerable responsibility on local governments – along with other sectors of society, other levels of government and the international community – but it also provides a framework for action that has the potential for creating inclusive and vital cities, not only for children but for everyone.

The development of human rights during the last century has been fuelled by a growing discomfort with the notion that any one group of people can legitimately be considered the property of another, or be excluded from rights extended to others. Slavery is no longer legally tolerated, caste systems are being dismantled, and women are realizing their right to self-determination in growing numbers. Children and youth are the most recent group to become the focus of debates on rights, and the history of children’s rights reflects more generally the changing public awareness of the meaning of childhood.1

The situation of children is complicated by their biological lifestage and the inherent complexities of the growing process. Young children in particular are dependent on their parents and others for protection and care. It is still difficult for many people to accept that children can be regarded as people with rights of their own, rather than as the property of their parents. For the most part, children are seen as lacking the status of full human beings and as being in training for adulthood.

But there is increasing recognition that our image of childhood is largely a social and cultural construction.2 Children at different times in history, and in different parts of the world, have been the focus of very different expectations. Their capabilities and requirements are determined at least to some degree by the needs and assumptions of those around them. Both economic realities and cultural patterns shape the experience of childhood in a given time and place.

Because this understanding varies between and even within cultures, there has been considerable disagreement on the issue of children’s rights. At one extreme it is argued that children, as human beings, should have the same rights as adults. At the other extreme are those who believe that children lack the competence to exercise rights, and that, protected as they are by their parents, they have no need for rights. Most of those involved in the child rights debate support an approach that recognizes both children’s need for protection and their developing potential to act on their own behalf. The broad trend in the child rights movement has been from a primarily protective stance towards a growing acceptance of children’s capacity to be active, contributing citizens, who deserve the rights to exercise that capacity.3

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (referred to in this book simply as the Convention or the CRC) was not the first international instrument to recognize the rights of children. The 1924 Geneva Declaration and the 1959 Declaration of the Rights of the Child, both broadly accepted within the international community, had considerable moral weight in promoting the rights of children to protection and care. But neither of these documents had the force of law, and a need was felt for a single legally binding convention.4

In response to a 1978 initiative by Poland, the Commission on Human Rights began developing such a legal treaty. After ten years of debate and preparation by an open working group, a final text was unanimously adopted by the General Assembly in 1989. This document went beyond the 1959 Declaration in a number of ways. Its provisions were more specific; it extended dramatically the civil and political rights offered to children, and it stressed the capacity of children to be not simply the passive recipients of protection, but active and involved bearers of rights.5 Acceptance of the Convention was rapid and widespread. By September 1997 the Convention was in force in 191 countries, and only two had failed to become parties to it. One is Somalia, which is currently without government, and the other the United States of America. No human rights convention in existence has achieved such broad or rapid acceptance.

The Convention is a significant document largely because of this remarkable level of support. It has established in a highly visible and definitive way the fact that the world’s children have a legal claim on the attention and resources of their governments and every sector of their societies. Not only has it clarified goals for children’s well-being; it has also set in place a system for monitoring implementation, without which progress would be less likely. The Convention has been embraced not only as a set of legal guidelines, but also as an educational tool and a frame of reference for all serious discussion pertaining to children and youth. It has become a platform for action for international agencies focused on children, and for many kinds of organizations within civil society.

THE PROVISIONS OF THE CONVENTION

Traditionally in the field of human rights there have been political pressures to distinguish between civil and political rights on the one hand, and social, economic and cultural rights on the other. In international law, these rights are enshrined within different covenants.6 Rather than distinguishing between these classes of rights, the drafters of the Convention insisted on an integrated approach and emphasized the indivisibility of rights as a significant principle. Protection, provision, and respect for a child’s capabilities are viewed from this perspective as complementary and mutually reinforcing supports for full well-being.7 The fulfilment of social, economic and cultural rights creates the conditions for full compliance with civil and political rights, and vice versa.

indivisibility of rights

The definition of the child

The Convention defines as a child every human being below 18, except in countries where majority is attained earlier (Article 1). This bill of rights is intended not only for young children, but also for adolescents who may already be functioning in many ways as adults. Adolescent mothers and working youth, for instance, deserve the level of support and consideration legally extended to children.

In a few areas the Convention sets specific age limits: it bars capital punishment and life imprisonment for children under 18, and it requires States to refrain from conscripting into armed services anyone below the age of 15.8 But it permits individual States to determine the age of majority and, in most cases, the minimum ages at which children may legally become involved in various activities. The ages at which children may legally marry, leave school, begin work, consume alcohol and obtain medical treatment without parental consent may vary from one country to another. It is expected, however, that States will review their legislation regarding such age limits in the light of the Convention’s general principles; nor may individual States absolve themselves from obligations to children under 18 even if they have reached the age of majority under domestic law.9

General principles

The Convention contains some fundamental principles which lay the gr...