eBook - ePub

Field Methods in Archaeology

Seventh Edition

- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Field Methods in Archaeology has been the leading source for instructors and students in archaeology courses and field schools for 60 years since it was first authored in 1949 by the legendary Robert Heizer. Left Coast has arranged to put the most recent Seventh Edition back into print after a brief hiatus, making this classic textbook again available to the next generation of archaeology students. This comprehensive guide provides an authoritative overview of the variety of methods used in field archaeology, from research design, to survey and excavation strategies, to conservation of artifacts and record-keeping. Authored by three leading archaeologists, with specialized contributions by several other experts, this volume deals with current issues such as cultural resource management, relations with indigenous peoples, and database management as well as standard methods of archaeological data collection and analysis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Field Methods in Archaeology by Thomas R Hester,Harry J Shafer,Kenneth L Feder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER

1

Introduction

Thomas R. Hester

Archaeology has undergone profound methodological and theoretical changes since the publication in 1975 of the sixth edition of Field Methods in Archaeology (for a succinct overview of changes in field methods, see Haag [1986]). Although this is a book on “field methods,” we have tried to incorporate numerous examples of these new directions. Despite the book’s New World emphasis, we have also attempted to provide information useful for fieldwork in any part of the world on the sites of both hunters and gatherers and complex societies. As Chapter 2 illustrates, the many different kinds of archaeology are being practiced these days by an amazing array of specialists.

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES

Cultural resource management (CRM) archaeology, just underway in the mid-1970s, has dominated American archaeology in the 1980s and 1990s (Adovasio and Carlisle 1988) and is also conducted in other parts of the world (for its impact on British archaeology, see McGill 1995). CRM, or “rescue,” archaeology seeks to deal with the effects on archaeological sites of construction done under state or federal permit (Knudson 1986). The authors have been involved, at various levels, in this work and have tried to integrate CRM goals with what we continue to believe are solid field methods. McHargue and Roberts (1977) have published a field guide for “conservation archaeology,” but it is now rather outdated. A number of paper-length syntheses and monographs specifically relating to method and theory in CRM archaeology have also been published (see Chapter 2).

Site formation processes have also attracted much attention in recent years, in large part as a result of Schiffer’s (1987) study. Formation processes must be viewed, in many cases, in a broad geomorphological perspective; we recommend a recent volume by Waters (1992) as an easy-to-read guide to the subject. In addition, Courty et al. (1989) introduce geological micromorphology to the study of site-deposit accrual. The whole issue of deposition is also part of soil science and the evolution of landscapes (Holliday 1992). Indeed, geoarchaeology and other things “geo-” are at the forefront of archaeology today; for example, geophysical site detection methods are common (with two examples being the work of Sheets [1992] and Roosevelt [1991]), along with forms of remote sensing (e.g., Donoghue and Shennan 1988).

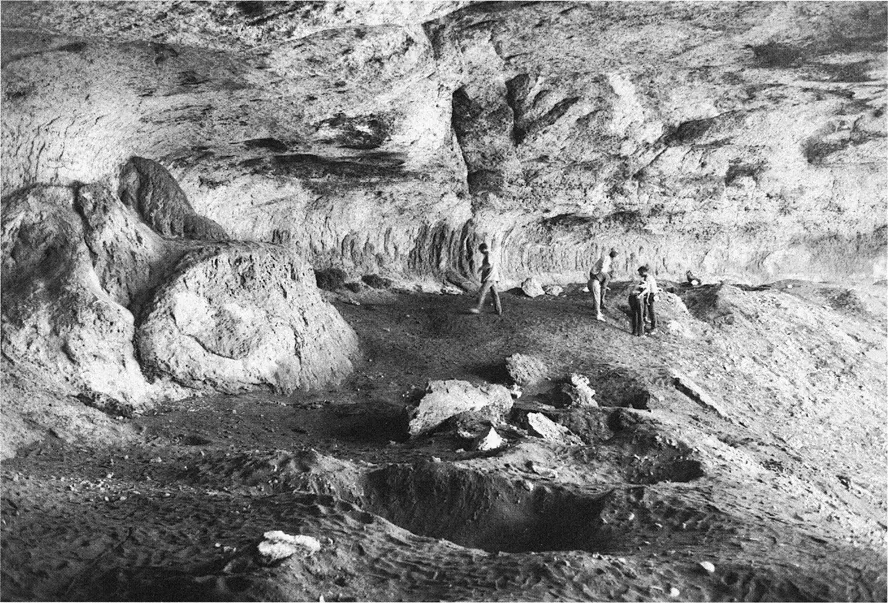

Site destruction and concerns for site preservation are a major issue in contemporary archaeology and the focus of a considerable literature. The subject is often intertwined with CRM studies. Of equal concern is the rapid disappearance of sites at the hands of relic collectors and pothunters (Figure 1.1). We are pleased to see that in many states the number of avocational archaeologists is increasing dramatically and that they are deeply involved in site protection (Patterson 1988)—and also that the Society for American Archaeology, through its Don E. Crabtree Award, has provided annual recognition to outstanding avocationals in the New World, with awards since 1988 having gone to both Americans and Canadians.

Public education is clearly one key to halting the looting of sites, and all archaeologists—professional, avocational, and students—need to be involved in talks to civic clubs and school classes and in the writing of articles and books that convey the results of archaeological fieldwork (and the importance of those results) to the general public (e.g., Shafer 1986). The public also needs to be cured of its infatuation with the “mystical” side of archaeology (for excellent efforts in this cause, see Feder [1990a] and Williams [1991]). Many states have introduced an Archaeology Awareness Week (in Arizona and Texas, this has been expanded to Archaeology Awareness Month!). Archaeologists should do everything possible to support and expand such efforts. I am unaware of similar observances in other countries but hope that they will be developed as part of public education.

Another approach to site preservation is the purchase and protection of sites through the privately funded efforts of the Archaeological Conservancy, an organization that clearly deserves much support. Write for membership information to 5301 Central Avenue NE, Suite 218, Albuquerque, NM 87108-1517.

In addition, there is a growing literature on the value of the “site” as an archaeological concept (Dunnell and Dancey 1983). Ebert (1992) has articulated his concerns about overemphasis on “sites” and a lack of concern with the archaeological record elsewhere in the landscape. Foley (e.g., 1981) has also written extensively on “off-site” archaeology.

Also a highly sensitive issue today is the handling of human remains and associated grave objects. In the United States, grave furnishings, sacred objects, and burials may be subject to reburial under the terms of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, enacted by Congress in 1990, and through laws passed by individual states. This issue has led to considerable acrimony between some Native Americans and some archaeologists. Additional details are presented in Chapters 2 and 11.

THE BURGEONING LITERATURE

The number of archaeologists, the number of archaeological projects, and the number of archaeological publications have increased dramatically in recent years. There is little one can do to keep up with the literature, especially the so-called gray literature resulting from some CRM projects. Efforts have been made to organize the burgeoning CRM and traditional archaeological literature through the compilation of archaeological bibliographies (e.g., Anderson 1982; Ellis 1982; Heizer et al. 1980; Weeks 1994), the publication of abstracts (either nationally, Abstracts in Anthropology, or by state, e.g., Abstracts in Texas Contract Archaeology), and by assembling archaeological encyclopedias (e.g., Fagan, in prep.; Evans and Webster, in prep.; and the multivolume Enciclopedia Archeologica to appear in Rome in the late 1990s). Although our editors would doubtless have preferred that the References Cited section of this book be much briefer, we have created a rather formidable listing, one we hope will serve as a useful reference tool.

Figure 1.1 Potholes representing looting activity at a rockshelter in the lower Pecos region of southwestern Texas.

This revision of the Field Methods lineage is but one of a number of field guides. We note in particular Joukowsky (1980), an effort that has broad coverage but is based largely on excavations in the Mediterranean region; Fladmark (1978, and numerous printings thereof), which has a step-by-step orientation and much attention to logistics; Dancey (1981), a small volume that admirably integrates goals, formation processes, and research design with field methods; Barker (1982), focusing largely on British archaeology but with approaches to field methods that can be used at many sites; Newlands and Breede (1976) on Canadian field methods; and Dever and Lance (1978), a handbook for the excavation of Bronze and Iron Age sites in the Middle East.

There are also notable, and more specific, contributions, such as Dillon’s (1989) Practical Archaeology, with chapters ranging from field mapping to site survey by muleback! A popularly written volume including much about field and lab methods is McIntosh’s (1986) Practical Archaeologist. Local societies are also preparing field and lab manuals; one that I have used in several field schools is by Hemion (1988). Finally, fieldworkers ought to look at Australian Field Archaeology (Connah 1983). Although specific to Australia, its 19 chapters cover a vast array of topics, including terrestrial photogrammetry, aerial photography, geoarchaeology, rock art recording, and report writing and publication—subjects of interest to archaeologists worldwide.

The illustration of archaeological finds, so critical to any report, is covered in several guides, especially Addington (1986), Adkins and Adkins (1989), and Dillon (1985).

ARCHAEOLOGY AND ARCHAEOLOGISTS

As the reader will learn, there are many definitions (and kinds) of archaeology. And, the vast majority of the public has little knowledge of what an archaeologist does. At cocktail parties, you invariably meet a few people who “always wanted to be an archaeologist” (but became physicians or lawyers because they knew they “couldn’t make any money doing archaeology”). And, of course, most others you meet will think that you study dinosaurs and fossils. My youngest daughter, having grown up with an archaeologist, with his messy office and frequent absences for fieldwork, wrote the following unsolicited definition of an archaeologist some years ago and left it on my desk. The typewriter is gone now and the word processor is running, but the other aspects are aptly stated:

The Archaeolgist:

A person with a lot of files, books, flints, artafacts, pictures, drawers. Well, he has a hole lot of things. He goes on digs a hole lot. He has a typewriter; he uses it all the time. I should know, I’m a daughter of a archaeolgist.

Amy Hester

Age 8 (1985)

Age 8 (1985)

One final note about who archaeologists are and how archaeology is done. Our advice—indeed our warning—to the reader of this and similar books is that field archaeology cannot be done “cookbook” style. Fieldwork requires much advance planning and the ability to modify strategies in the field if conditions warrant. We intend this book to provide some guidance in certain areas of major concern in field archaeology. We also point out in many of its chapters that the key ingredient to a successful field project is to be a careful observer, a diligent recorder—and always to be thinking about what you are doing in the excavation of irreplaceable resources.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

Field Methods

Barker 1982; Dancey 1981; Dillon 1989; Fladmark 1978; Haag 1986; Joukowsky 1980; Sharer and Ashmore 1993; Thomas 1989

Contemporary Issues

Adovasio and Carlisle 1988; Ebert 1992; Knudson 1986; Schiffer 1987; Sheets 1992; Waters 1992

CHAPTER

2

Goals of Archaeological Investigation

Harry J. Shafer

What are the goals and objectives of archaeological fieldwork? How do they relate to those of the discipline itself? An ultimate goal of archaeology—and an appropriate definition for the discipline—is the study of human behavior and cultural change in the past (Trigger 1989:371). Such a broad definition allows for the distinction of several kinds of archaeology, each with its own set of goals. Archaeology, not unlike the cultures and societies under its focus, has undergone many changes over the past century; with each change, new goals have replaced or amplified old ones (Trigger 1989:370–411).

KINDS OF ARCHAEOLOGY

As recently as two decades ago, archaeology taught in American universities could conveniently be divided into studies of the classical world, prehistoric archaeology, and historical archaeology. Today, however, these divisions hold less-distinctive meaning because the more eclectic goals of anthropological archaeology and studies of human ecology have greatly influenced the aims of classic and historical archaeology. We think it is appropriate to outline some of the differences in the goals of various subareas of archaeology.

In America, or in Americanist archaeology, prehistoric and historic archaeology are usually taught under the discipline of anthropology, which is the study of humankind in the broadest sense. Archaeology, which concerns itself with the remains of the human past, is one of the subdisciplines of anthropology that studies the development of human culture through time. The advantage archaeologists have is in the depth and breadth of the material record, the large blocks of time within which they may examine culture change and development.

Archaeology of the Classical World

In the United States, archaeologists who specialize in the classical world, or classical archaeologists, are usually associated with classics or art history studies. They generally are art historians or classics scholars who use the methods and techniques of archaeology to recover the art and architectural remains of classical civilizations. Classics scholars take advantage of the ancient written records and texts in Greek, Latin, Sumerian, and Egyptian to help them document and understand these ancient civilizations. Working with these scholars are art historians who use art styles and architecture to understand the past (Figure 2.1).

The goals of classical archaeology are by its nature historical in orientation, focusing on details of architecture, recovery of art objects, the tracing of art and architectural themes, and the development of written language. Cl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Goals of Archaeological Investigation

- 3 Research Design and Sampling Techniques

- 4 Site Survey

- 5 Methods of Excavation

- 6 Data Preservation: Recording and Collecting

- 7 The Handling and Conservation of Artifacts in the Field

- 8 Archaeological Field Photography

- 9 Archaeological Mapping, Site Grids, and Surveying

- 10 Stratigraphy

- 11 Excavation and Analysis of Human Remains

- 12 Excavation and Recovery of Botanical Materials from Archaeological Sites

- 13 Basic Approaches in Archaeological Faunal Analysis

- 14 Chronological Methods

- Appendix A—Tables of Equivalents and Conversion Factors

- Appendix B—Sources of Supplies and Services

- References Cited

- List of Contributors

- Credits

- Index