- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Child Labour in South Asia

About this book

Child labour is a serious and contentious issue throughout the developing world and it continues to be a problem whose form and very meaning shifts with social, geographical, economic and cultural context. While the debate about child labour practice in developing countries appears to be motivated by growing competition in labour intensive products brought about by globalization, studies on this issue are both sparse and lopsided. This important book aims to shed light on this debate by documenting the experience of South Asian developing countries which have experienced rapid income and export growth. Based on evidence from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, this volume aims to improve our understanding about the link between trade, growth and child labour practices, as well as management of child labour in developing countries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Child Labour in South Asia by Kishor Sharma, Gamini Herath in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Theoretical and Empirical Debates on Child Labour

Chapter 1

Labour and Economic Development: Emerging Issues in Developing Asia

Introduction

Child labour is a serious and contentious issue throughout the developing world as it is demeaning and damaging to a child’s health and intellectual development (UNICEF 1997, Ray 2004, Ray 2000). However, what counts as child labour and who counts as a worker is still a controversial issue and many jobs fall outside the law. Child labour continues to be a problem whose form and very meaning shifts with social, geographical, economic and cultural context. In some regions child labor has persisted or reconstituted from the customary into the exploitative. Low wages, irregular hours of employment, exploitative slavery, atrocious working conditions, lack of contracting power all characterize child labour in many countries. Generalization is elusive because there are significant variations among the different kinds of work done, which can range from family help for parents to industrial work.

Child labour is the basis of economic activities in many Asian developing countries and many consumer goods including export commodities such as carpets, clothing, and agricultural commodities are produced by them. Child labour practices also occur in a range of potentially hazardous tasks such as gem mining, construction, commercial farming, and transporting goods and services. Poverty, absence of accessible schools in the villages, and the shortage of teachers prevent children from attending school and keep them in employment with megre returns (Ravallion and Wodon 2004).

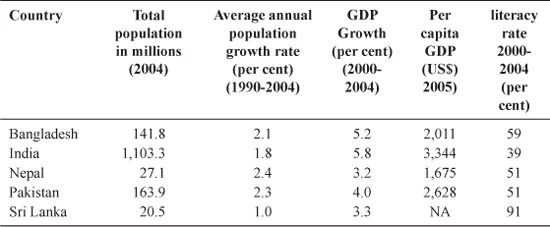

It is estimated that about 60 per cent of world’s children live in developing Asia and about 19 per cent of these children are victims of child labour practices. Within Asia, South Asia has a high incidence of child labour and this varies significantly between countries. For instance, children’s workforce participation rates-the number of child workers to the child population-range from just above 5 per cent in India to 42 per cent in Nepal (see Table 1.1 and chapter 5 by Sharma in this volume). The lower percentage of child labour in India appears to be mainly due to rapid economic growth and export expansion brought about by economic liberalisation since the early 1990s, while the high incidence of child labour in Nepal appears to be mainly due to slow economic growth caused by civil unrest (Table 1.1)1

Table 1.1 Economic and social indicators of South Asian countries

Source : UNICEF available at <http;//www.unicef.org/infobycountry/>

South Asia is one of the highly populated regions in the world, providing shelter for about 1.436 billion or 22 per cent of the world’s population. It is also the region which has experienced rapid economic growth since the 1990s due to liberalization in trade and investment which began in the early 1990s. In comparative perspective, India has grown faster than the other economies in the region. For instance, during 2000-2004 India’s GDP grew at 5.8 per cent per annum compared to Nepal’s GDP which grew at only 3.2 per cent per annum during the same period. India is also the country with the largest population and per capita GDP, while Nepal is the smallest country in terms of both population and per capita GDP.

Agriculture appears to be the backbone of the South Asian economies, although its contribution to GDP has gradually declined as service and industry sectors expanded in response to economic liberalization of the early 1990s. Table 1.1 presents key economic and social indicators of South Asian countries that are covered in the present study.

Since the welfare of working children is a real issue, it is important to examine the nature and extent of the problem more closely to gain better insights into child labour practices and to develop policy measures keeping in mind country-specific peculiarities. This is the purpose of this volume.

Some salient aspects of child labour in Asia

Many South Asian countries depend heavily on agriculture which in some countries contribute more than 50 per cent of GDP. Agriculture is the predominant occupation of many families with large number of children and child labour is a pre-requisite in the family’s farm. Poor families cannot afford to hire labour due to poverty. Poorer sections of the community such as tenant farmers are worst affected because the tenancy system forces tenant farmers to use children in the fields to meet the terms of the labour contract. Some landlords can even prohibit children of tenants living on estates from sending their children to school during harvesting (Otanez et al 2006).

Rapid historical increases in agricultural productivity are expected to continue in the future and the need for labour remains high. There has been gender bias in the agricultural technologies such as the Green Revolution where the demand for female labour has been comparatively higher which adversely affected female childrens’ welfare (Cigno and Rosati 2002). Lack of efficient infrastructure to supply water and energy resources compel the use of child labour to gather water and fuel wood. The decline of the natural resource base in many developing countries due to excessive harvesting mean that the task of gathering water and fuel has become even more strenuous and longer hours need to be spent (Pachauri et al 2004). These affect childrens’ nutrition, health and recreational needs. In general, solving the problem of child labour becomes complex and decisions involve difficult tradeoffs between work and schooling by poor families. The labour resources need to be managed in order to improve their quality and ensure that economic development does not degrade their health. Parental perceptions of child labour need to be changed through education and intervention strategies.

The unprecedented increases in population and economic growth and rampant poverty during the last few decades have diminished the capacity of countries to eliminate child labour. The world’s population has reached 6.5 billion in 2005. At plausible rates of growth in population and income per capita, world GDP in 2050 could be four times what it is today (Kirk and Ian 2004). Rapid socioeconomic improvements driven by increased income and wealth can increase the demand for child labour.

Globalization and liberalization of markets and intensifying competition in commodity markets have increased the demand for labour in developing countries. There has been significant outsourcing of economic production from the developed countries to the developing countries due to globalization. With globalization of markets, children have become more susceptible to global economic forces and the actions of governmental and private industrial agencies.

Child labour policies in perspective

As the complexity of the problem increases, it becomes more difficult for policy makers to identify better management alternatives that are effective. This difficulty has increased the demand for even more effective policies. The neoclassical economic approach would have limited applicability in such situations. Over the past two decades, considerable attention has been focused on developing new policies to identify better alternatives for managing child labour. New insights need to be gained to improve the implementation and effectiveness of child labour policies.

Government intervention is required to improve adult wages and address child labour problems but such action is unlikely because some industries dominate the government. Some industries are major foreign exchange earners. This creates conflicts of interests between government and industry representatives and pervasive corruption. These challenges are daunting but there is little doubt that both children and adults would be far better off than they are under the current situation were payments of better wages to occur.

Despite minimum working age and constitutional protection given to protect children from economic exploitation, child labour can interfere with their education and development. Governments lack implementation measures and do not enforce this law. Despite being signatories to many conventions, there is no meaningful enforcement of any of these provisions, and child labour is increasing in some countries. There is a need to reevaluate which actions if any, would be appropriate to effectively reduce the incidence of child labour.

If governments are genuinely committed to improving the socio-economic conditions of child labour and their parents, they should establish and enforce policies not to purchase products made using child labour. They should also conform with the core conventions of the ILO that cover not just child labour but a range of labour rights concerns, adopt monitoring programs to ensure that third party monitors will visit farms periodically to perform audits and also commit public reporting of results of monitoring workplaces.

National and international organizations consider community participation as a critical component in collaborative efforts to resolve the child labour problem. Involvement of community groups in the planning, management, and policy analysis helps to resolve conflicts, increase public commitment and the capacity of governments to respond to public needs with policy alternatives acceptable to the community. Community involvement in decision making has been inadequate and public consultation has been ineffective. Community participation focuses on people and their needs, and engage them in developing a common orientation and shared future vision for child labour.

Child labour was a problem in the developed countries of the world centuries ago. During the industrial revolution child labour was a crucial element and widespread poverty at that time made child labour available. However, over a long span of time, beginning from legal protection, and other conditions such as regular medical checkups for factory labour and the so called ‘half-time’ work which permitted children to work but study at the same time were adopted which over time minimized the child labour problem (Pierick and Houwerzijl 2006). These countries followed several phases in eliminating child labour over time and whether the contemporary developing countries should follow the same path in eliminating child labour remains a contentious issues but innovative and more efficient policies may reduce this time span considerably.

Purpose and structure of the volume

Despite growing debate about globalization and child labour practices, country-specific studies on this topic are extremely limited. The purpose of this volume is to bridge this gap in the literature by examining the experience of South Asian countries which have experienced rapid growth since the early 1990s. This is also the region which has a high incidence of child labour practices. The examination of the experience of countries from this region would provide a better insight into this important socioeconomic issue. The volume is divided into eleven chapters. Following this chapter on introduction, chapter 2 evaluates the theoretical and empirical literature available to assess the scope, intensity, trends and strategies adopted to combat child labour. The chapter pays particular attention to poverty and role of education, supply and demand factors and impact of trade liberalisation to obtain a clearer understanding of the nature of the problem. Although not exhaustive, it presents several theoretical models including credit constraint models and provides a stimulating look at what could be done to combat negative consequences of child labour.

Chapter 3 is a theoretical model and attempts to view child labour from a cumulative causation perspective. It provides an overview of how the theory is based on the concept of cumulative cycles of growth and decline, a description of its focus on change, including change through invention and technical progress, and an outline of its emphasis on the influence of history on economic development. This is followed by a discussion of how child labour can be explained through the economic and socio-economic bases of the theory. It also highlights how political and institutional factors can be used as a basis for policies and programs to eliminate poverty and child labour.

Chapter 4 describes an integrated model for India by the author who has first hand experience on child labour. The chapter discusses (a) the current global trends in child labour, both in terms of the concept and extent of the problem; (b) strategies to deal with the child labour issue and their limitations; and (c) develop an integrated approach to effectively reduce child labour and provide support services to children to free themselves from child labour, particularly the worst forms of child labour. This chapter aims to raise awareness of child labour in order to mobilise necessary resources and create conditions for children to realise their human potential.

Chapter 5 presents an overview of the issues regarding trade and child labour, the state of child labour in South Asia and the role of the WTO in minimizing child labour. The examination of the experience of South Asian countries is particularly relevant because a significant number of working children are found in this region and the incidence of child labour varies significantly between the countries in the region.

Chapter 6 provides an evaluation of the role of legislation to control child labour in Bangladesh. It provides an account of the various Laws and Acts passed by the legislature and the problems of efficiently implementing such laws. Bangladesh is an extremely relevant case study because of the wide prevalence of child labour, high child malnutrition, poor enrolment in schools, frequent natural calamities, and poor implementation of labour legislation.

Chapter 7 discusses the child labour problem in India, a country with a large percentage of child labour and many industries employing child labour. Though the percentage of working children is lower in India than in many other developing countries, it has the largest number of working children in the world. The child labour issue is comparatively well researched in India and this chapter examines recent statistics, trends and policies and their effectiveness.

Chapter 8 takes a philosophical stance of the child labour issue and specifically looks at the issue in India. It explores the broader perceptual, contextual and historical frameworks that determine the attitudes towards child labour. It then raises specific issues on child labour and provide an analysis of each in detail.

Chapter 9 provides a detailed discussion of the strategies adopted to minimize child labour in Nepal. Being a country with a high percentage of child labour, the issue is an important one. The Nepalese Government has initiated a Nepal Master Plan to minimize the incidence of child labour by the year 2014. The chapter provides detailed accounts of the various aspects of the Plan which contains significant initiatives to make a sizeable dent on the child labour problem in Nepal.

Chapter 10 looks at child labour in Pakistan where it has been a persistent problem. It presents the salient features of child labour market in Pakistan. The role of international covenants governing child labour and their impact in minimizing the problem are discussed. The need for integration and collaboration among the Federal Ministry of Labour, manpower and overseas Pakistanis, Provincial Labour Departments and the International Labour Organization (ILO) and civil society groups is emphasized.

Chapter 11 evaluates the child ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Part 1: Theoretical and Empirical Debates on Child Labour

- Part 2: Lessons from South Asia

- Index