- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Starch Research

About this book

What role did plant resources have in the evolution of the human species? Why and how have plants been managed and transported to new environments? Where, how, and why were plants domesticated, and why do the patterns vary in different parts of the world? What is the relationship between the intensification of food production and the rise of complex societies? Numerous new studies are using starch granules discovered in archaeological contexts to answer these questions and improve our knowledge of past human behavior and environmental variation. Given the substantial body of successful research, the time has clearly come for a comprehensive description of ancient starch research and its potential for archaeologists. This book fills these roles by describing the fundamental principles underlying starch research, guiding researchers through the methodology, reviewing the results of significant case studies, and pointing the way to future avenues for research. The joint product of over two dozen archaeological scientists, Ancient Starch Research aims to bring the important new field of ancient starch analysis to the attention of a wider range of scholars and to provide them with the information needed to embark on their own research.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Starch and Archaeology

Robin Torrence

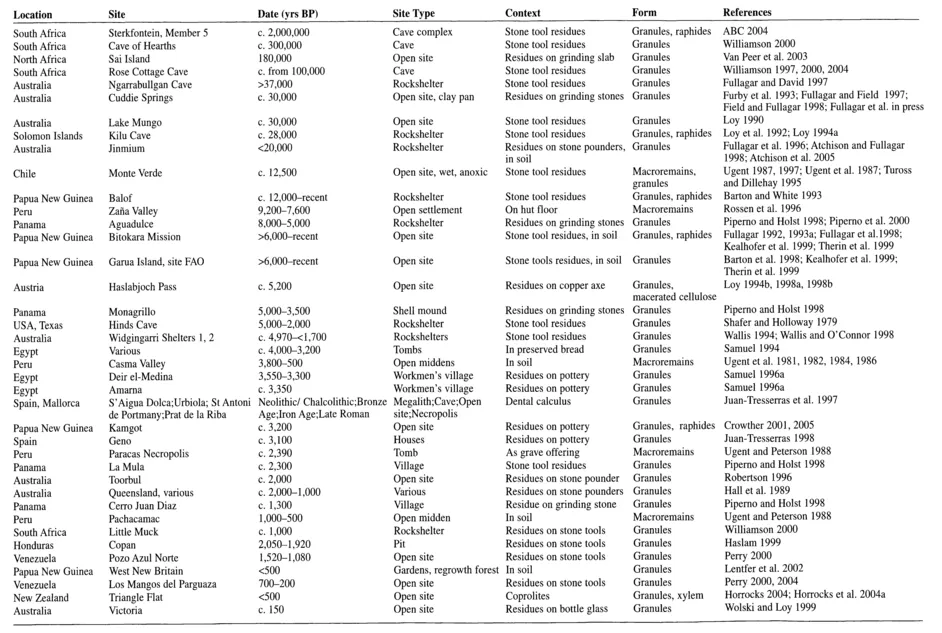

Starch is surprisingly ubiquitous in the archaeological record. It has been found in deposits as much as two million years old and in highly varied settings spread across the globe. It has been recovered from the ideal conditions provided by dry caves or tombs as well as in places where organic preservation is exceedingly poor, such as open sites in the humid tropics. Starch granules have been identified within desiccated and/or charred tubers, preserved bread, as part of residues in ceramic vessels, adhering to the edges of stone tools, inside coprolites, within dental calculus, and in soils taken from rock shelters, open settlements, gardens, and forests. The wide temporal, geographic, and contextual range of the archaeological contexts in which starch has been studied is illustrated by the list in Table 1.1. Starch is clearly plentiful and widespread in contexts dating from ancient to modern, but what contribution can it make to archaeological research?

The archaeological potential of ancient starch was recognised a century ago (Wittmack 1905), but scholars were surprisingly slow to capitalise on this valuable source of information about past environments, plant use, diets, and artifact functions. Ancient starch research has really only become established in the past twenty years or so, but it has rapidly developed as a sophisticated new branch of research. A great deal of basic background work has been completed, methodologies have been put into place, and the pace of research output on ancient starch has significantly increased in recent years.

A rapidly growing number of case studies representing many parts of the world have produced exciting new data about vegetation histories, plant domestication, diet, mobility patterns, and artifact function. Selected as groundbreaking research by Nature or Science, recent studies incorporating data on ancient starch have reported plant cultivation earlier than expected, which in some cases may represent the first hard evidence for domestication both in Panama (Piperno and Hoist 1998; Piperno et al. 2000) and in Uruguay (Iriarte et al. 2004) as well as in Papua New Guinea (Denham et al. 2003), all places thought by many to be far from the supposed heartlands of agriculture. Pioneering research using starch residues preserved on stone tools had already shown that some plants were transported far from their native lands thousands of years before they were supposedly cultivated, as in the case of taro starch granules that were found on stone tools dating to at least 28,000 years ago in the Solomon Islands (Loy et al. 1992). An important innovation for studying past diets has been the extraction of starch from coprolites. Sweet potato and bracken fern starch found in human and canine coprolites is the first direct evidence for these important food sources in prehistoric New Zealand (Horrocks et al. 2004a).

Studies based on stone tool residues have produced surprising and significant results concerning the importance of plants in the past. For instance, Williamson (2004) has shown that the majority of stone tools deposited at the site of Rose Cottage Cave in South Africa during the Middle and Late Stone Ages were used to process plants rather than to butcher animals, as was previously assumed. Her work also challenged ideas about gendered roles in the far distant past. In another study in which starch has contributed to our understanding of the earliest modern human behaviour, Van Peer et al. (2003) found starch granules on grinding slabs dated to around 180,000 BP. This represents one of the earliest instances of complex food processing among our human ancestors. Perry's (2004, in press) study of starches has seriously called into doubt the ascription of particular stone tools as parts of manioc graters and therefore challenged the role of this food source in prehistoric Venezuela. Fullagar (1992, 1993a) questioned the importance of recent ethnography as a source for reconstructing prehistoric stone tool use in Papua New Guinea, because he documented the unexpected dominance of plant processing rather than shaving and cutting of human skin in the assemblages he studied.

Starch extracted from sediments has provided evidence for changes in land use (Therin et al. 1999) and helped reconstruct activity areas on sites in Australia (Balme and Beck 2002) and at Copan in Honduras (Haslam 1999). Starch has also assisted in identifying which plants were grown within various types of agricultural features in New Zealand (Horrocks et al. 2004b).

Finally, an exciting contribution ot ancient starch research has been the reconstruction of methods for making beer and bread in ancient Egypt (Samuel 1996a, 1996b, 2000). Surprisingly, Egyptian scholars had got the recipes for these important foods wrong and it was detective work based on damage to starch granules combined with other evidence that produced a more accurate picture of the manufacturing methods for these key sources of food.

This sample of the rapidly expanding number of exciting new case studies demonstrates conclusively that ancient starch has an important role to play in archaeological research, especially when tied in with other paleobotanical and archaeological techniques. Starch analysis can extend the range of our knowledge as well as the ability to make inferences about past human behaviour and environmental variation. Given the substantial body of successful research, the time has clearly come for a comprehensive description of ancient starch research and a guide to methods that will foster further work. This book fills these roles by (1) describing the fundamental principles underlying starch research (e.g., biology, human uses of starch, taphonomy); (2) guiding researchers through the methodology; (3) reviewing the results of significant case studies; and (4) pointing the way to future avenues for research. Ancient Starch Research aims to bring the important new field of ancient starch analysis to the attention of a wider range of scholars and to provide them with the information needed to embark on their own research.

Starch and The Big Questions

What role did plant resources have in the evolution of the human species? Why and how have plants been managed and transported to new environments? Where, how, and why were plants domesticated and why do the patterns vary in different parts of the world? What is the relationship between the intensification of food production and the rise of complex societies? Finding out exactly which starchy plants were consumed in the past and how dietary choices were made, understanding the processes leading to domestication, and explaining changes in subsistence strategies and the adoption of new foods are high research priorities shared by archaeologists working all over the globe. The recent development of ancient starch research has grown out of the need for relevant data to answer 'big questions' in archaeology. For this reason much of the earlier work has been strongly problem-oriented and led to important new discoveries.

Hather (1991) has shown that tubers (a convenient shorthand that will be used throughout the book for 'swollen vegetative storage organ—root, rhizome, corm, tuber, stolon, etc.—consisting largely of starch-bearing parenchyma' [Hather 1994a: 719]) were utilised as far back as the Paleolithic period in Europe and has argued that they probably continued to form a significant component of the diet even after the introduction of domesticated seed crops. To find out when tubers were first incorporated into hominid diets is an important research agenda because some archaeologists have theorised that starchy tubers were a very significant if not crucial part of past human subsistence patterns. O'Connell et al. (1999) and Wrangham et al. (1999) have proposed that a critical factor in the evolution of humans and the expansion of Homo erectus out of Africa was the ability to process wild yams. Cooking could have increased the energetic value of this food and the exploitation of yams also might have enabled populations to survive through the much drier conditions of that time (Box 1.1). The recovery of ancient starch could have an important role to play in testing this theory.

Some time ago Sauer (1952) proposed that the earliest agriculture was based on the domestication of tubers and roots in Southeast Asia. His theory was derived from the many different types and importance of root crops in this region. Matthews (Box 1.2) has also argued that the widespread distribution of one of these, taro, suggests

Table 1.1. The very broad temporal and geographic ranges of archaeological contexts in which starch has been preserved (prepared by Peter J. Matthews and Robin Torrence).

Box 1.1. Tubers And Human Evolution

James F. O'Connell

Many important developments in human evolution are thought to have been connected with changes in diet. Those that occurred prior to the late Pleistocene are typically linked with increased consumption of meat, usually from large animal prey (Klein 1999). Although changes in the use of plant foods are sometimes also mentioned as contributing factors, this possibility is rarely taken seriously, mainly because of a perceived absence of archaeological evidence. A common argument is that while large animal bones are an obvious part of the paleolithic record, plant food remains are not; hence plants 'cannot' have been an important component of early human diets, let alone the catalyst for major evolutionary change (e.g., Kaplan et al. 2000).

Arguments about the evolution of early African Homo erectus (aka H. ergaster) are a case in point. Dated to about 1.8 Ma, this form differs from earlier hominids in its larger body size, reduced sexual dimorphism, simplified digestive anatomy, greatly increased geographical range, delayed maturity, increased longevity, and probable earlier age at weaning (O'Connell et al. 1999; Wood and Collard 1999). Collectively, this suite of traits marks the most important development in human evolutionary history between the adoption of bipedalism (>4.0 Ma) and the appearance of modern humans (~100 ka). Changes in body size, digestive anatomy, and geographical distribution all point to a shift in diet. The life history changes further suggest the emergence of a pattern of long-term offspring provisioning, similar if not identical to that typical of all modern humans, but unknown among other primates. The first challenge is to provide a theoretically well-warranted hypothesis that links these various developments. The second is to devise an archaeological test of the new hypothesis.

Conventional approaches to the problem routinely emphasize increased meat-eating as the key behavioral innovation. More meat, especially from large ungulates, is said to have provided the dietary 'surplus' that fuelled changes in body size, underwrote delayed maturity and other shifts in life history, and facilitated the use of a broader range of habitats. The argument draws apparent support from the archaeological record, specifically the repeated association of stone tools and humanly processed large animal bones in sites of Plio-Pleistocene age, which are roughly contemporary with the first appearance of earliest H. erectus (Klein 1999).

Archaeological data notwithstanding, there are good reasons to be skeptical of the argument based on meat eating. In order to support early weaning and a long period of juvenile development, provisions must be available on a reliable, near-daily basis; yet modern hunter-gatherers, equipped with traditional weapons, cannot provide meat on anything like that schedule. Records for the modern Hadza, living in a game-rich habitat in northern Tanzania similar to that occupied by early H. erectus, indicate an average success rate of only one large animal every thirty hunter-days (Hawkes et al. 1991). Groups of six to eight men commonly co-resident in a single camp often go for weeks without making a single kill, despite hunting every day. Less well armed, H. erectus is unlikely to have done as well, let alone much better. Meat may have been an important part of early human diets, but its consumption was probably not central to the emergence of early humans.

Plant foods, particularly underground storage organs ('tubers' in common parlance), have long been identified as a potentially important food source for early H. erectus (e.g., Coursey 1973); but until recently no argument linking their use to changes in morphology and life history has been available. Hawkes and colleagues now provide one (Hawkes et al. 1998; O'Connell et al. 1999; see also Wrangham et al. 1999). Specifically, they suggest that a trend toward increased seasonality, roughly contemporary with the first appearance of H. erectus, reduced the availability of foods (especially fruit) that very young children could take on their own, forcing women to provision their offspring through lean seasons. If women toward the end of their own reproductive careers provided some of the necessary provisions, especially to their grandchildren, then their daughters might have been able to wean those grandchildren earlier and move to the next pregnancy sooner (Figure 1.1). Not only would fecundity be increased, at no cost in weanling survivorship, but selection would likely also favor increased longevity, which would in turn promote delayed maturity and larger adult body size, consistent with general mammalian patterns (Hawkes et al. 1998).

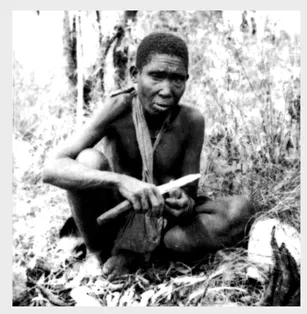

Figure 1.1. Hadza great-grandmother Wande pauses in the course of a tuber collecting trip in the Eyasi Basin, northern Tanzania during the early dry season, 1986. Older women may have played an important role in human evolution by providing tubers that enabled young children to be weaned at an early age. Photo by James O'Connell

Tubers may have been among the resources used to provision young children so that they could be weaned at an earlier age. Tubers occur at high densities (up to 10 tonnes/ hectare), are rich in carbohydrates (up to 90 percent dry weight), and are widely exploited by modern temperate and tropical foragers; yet they are often not taken by younger children, mainly because of their occurrence at reasonable depths below ground surface, the complexity of their carbohydrate content, or the chemical defenses they contain. In contrast, adults contend with most of these problems quite easily and often gain returns high enough to support themselves and one or two others, with relatively little day-to-day variance. If a similar situation occurred in the past, then tubers could have been the crucial resource that provisioned young children and thereby enabled H. erectus populations to be so successful.

The difficulty faced by archaeologists is to test the suggestion that tubers actually played this role for H. erectus. This problem is now und...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF BOXES, TABLES, AND FIGURES

- LIST OF PLATES

- PREFACE

- Chapter 1 STARCH AND ARCHAEOLOGY

- Chapter 2 BIOLOGY OF STARCH

- Chapter 3 MICROSCOPY

- Chapter 4 STARCH PATHWAYS

- Chapter 5 TAPHONOMY

- Chapter 6 REFERENCE COLLECTIONS

- Chapter 7 DESCRIPTION, CLASSIFICATION, AND IDENTIFICATION

- Chapter 8 STARCH IN SEDIMENTS

- Chapter 9 STARCH ON ARTIFACTS

- Chapter 10 MODIFIED STARCH

- Chapter 11 LOOKING AHEAD

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

- LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ancient Starch Research by Robin Torrence, Huw Barton, Robin Torrence,Huw Barton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.