C H A P T E R 1 | A Map of the Terrain of Ethics |

CASE 1

The Boy Who Ate the Pickle

A 9-year-old youngster named Yusef Camp who lived in inner-city Washington ate a pickle that he had bought from a street vendor. Soon after eating it he went into convulsions and collapsed on the sidewalk. A rescue squad took him to the nearest emergency room where his stomach was pumped. Tests revealed that the pickle contained traces of marijuana and PCP. The boy suffered severe respiratory depression and was left unconscious, unable to breathe for an unknown period.

The emergency room personnel restored respiration by putting him on a ventilator, but they were unable to restore him to consciousness or get him breathing adequately on his own.

The physicians concluded that his brain function was irreversibly destroyed and that there was no possibility of recovery. They might have simply pronounced him dead and then stopped the ventilator, but the situation soon became more complicated. Two of the attending neurologists were convinced that the patient’s brain was totally dead, but one believed that he had minor brain function still in place. So they were incapable of pronouncing the patient dead based on loss of brain function. Now the question became, What should they do? Their patient was still living but permanently unconscious, breathing only because he was on a ventilator.

The physicians pointed out that there was nothing more they could do except keep the ventilator running, perhaps indefinitely and maintain the boy in a persistent or permanent vegetative state. (The longest case on record of maintaining a patient in what is called a permanent vegetative state is over thirty-seven years.) The parents were Muslims, members of the Nation of Islam, who firmly believed in the power of Allah. They believed that Allah would intervene if it was his will, and that it was the physicians’ job to give Allah that opportunity. How should the physicians respond?

The physicians, the parents, and everyone else involved in this case face some difficult and controversial ethical choices. They need to determine the proper definition of death, the role of parents and other surrogates in deciding about medical care for a minor, the proper ethics of terminal care, the morality of using scarce medical resources, and the role that minority religious perspectives ought to play in modern, secular medical care. In order to sort out these disparate and complex ethical issues we need a map of the ethical terrain: an overview of the kinds of ethical issues at stake and the terminology for labeling the disputes. This chapter will provide a basic map of that terrain. Once that overview is in place, we can begin sorting out the issues facing Yusef Camp’s parents and physicians.

THE LEVELS OF MORAL DISCOURSE

The Level of the Case

Often in biomedical ethic, the discussion begins with a case problem. Someone faces a concrete moral dilemma or two people disagree about what in a specific situation is the morally appropriate behavior. Some people may mistakenly think that ethical choices do not occur all that often in medicine. They think that an “ethics case” is an unusual, special event. In fact, ethical and other value choices occur constantly, but, fortunately, in almost all situations the ethically correct course is obvious. The decision can be made with little or no conscious thought. Ethical choices have still been made— even if the decision maker does not even realize it. He or she can rely on well-ingrained moral beliefs and get by quite adequately. Occasionally, however, the choice does not come as easily. As in the case of Yusef Camp, the choice requires more careful, conscious thought. The physician faced with a choice may turn to colleagues or to a hospital ethics committee for advice. A lay person may turn to friends or to a trusted religious or secular group for guidance.

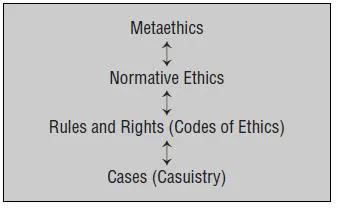

One kind of advice may come in the form of mentioning other cases that seem similar, cases that have been resolved in the past. They may be in the form of a Biblical story or a legal case about which the culture has reached agreement. These agreed-upon cases are sometimes referred to as “paradigm cases.” Most people can agree that, in matters of ethics, similar cases should be treated similarly. In fact, one of the identifying characteristics of an ethical judgment (as opposed to a matter of mere taste or preference) is this awareness that if the relevant features are similar, then cases should be treated alike. As long as people can agree on what should be done in the paradigm case and can agree that the new case is similar in all relevant respects, they will be able to resolve their problem. This approach relying on paradigm cases is sometimes called casuistry. As seen in Figure 1, this is the lowest or most specific level of what can be considered the four major levels of moral discourse. This figure is a simplified version of the more elaborate map of the ethical terrain that appears on the front and back inside covers of this book.

FIGURE 1 The Four Levels of Moral Discourse

Rules and Rights (Codes of Ethics)

But what if the basic ethics we learned as children does not settle the problem? What if we cannot agree on a paradigm case or cannot agree that our present problem is like the paradigm case in all relevant respects? We may, at that point, move to a second level of moral discourse, the level of moral rules and rights. Sometimes rules and rights tell us what is legal, but they may also describe what is ethical. Since not everything that is legal is also ethical (and not everything that is illegal is necessarily unethical), it will be important to note the difference. If a rule or a right is considered ethical, it will be seen as grounded in a moral system, an ultimate system of beliefs and norms about the rightness or wrongness of human conduct and character. Groups of rules or rights claims are sometimes called codes of ethics.

Yusef Camp’s physicians may consult the Code of Ethics of the American Medical Association to see whether that group considers it ethical to stop treatment in such cases. His parents might consult an Islamic code. Some of the parties in the dispute may bring out the Hippocratic Oath or a “patients’ bill of rights”

Sometimes the parties to an ethical dispute may cite a rule-like maxim. “Always get consent before surgery” or “a patient’s medical information must be kept confidential” are examples of such maxims. These rule-like statements are usually quite specific. A large number of them would be needed to cover all medical ethical situations. If there is agreement on the rule that applies, then the case problem might be resolved at this second level.

Sometimes these maxims are stated not as rules but as rights claims. The statement, “a patient has a right to consent before surgery” would be an example. So would the statement “a patient has a right to have his or her medical information kept confidential.” Rules are expressed from the perspective of the one who has a duty to act; rights claims from the vantage point of the one acted upon. Often rules and rights express the same moral duty from two different perspectives. “Always get consent before surgery” expresses from the health provider’s point of view the same moral notion that is expressed from the patient’s vantage point as “a patient has a right to consent before surgery.” They are then said to be “reciprocal.” If one person has a duty to act in a certain way toward another, that other person usually can be said to have a right to be acted upon in that way.

Medical professional, religious, cultural, and political organizations sometimes gather together collections of rules or rights claims. When they do, they “codify” them or produce a code of ethics. They can also take the form of oaths as in the Hippocratic Oath or directives as in the “Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Facilities.” When the statements are made up of rights claims, they are often called bills of rights as in the American Hospital Association’s “Patient’s Bill of Rights” or declarations as in the new “Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights.” Chapter 2 looks at various oaths, codes, and declarations, and sees what their implications are for cases like Yusef Camp’s. We will discover how controversial these codifications are. Proponents of such codes not only have to determine what rules and rights are appropriate, but also which humans (and non-humans) have the moral standing to have claims based on these rules and rights. Chapter 3 takes up this question of who has this moral standing. Here we address the question of whether Yusef Camp has the moral standing of a living human being or is already dead—according to a brain-oriented definition of death. We will also see the implications for the moral status of fetuses and non-human animals. We will at this point also confront the new controversy over the use of stem cells.

These rules and rights claims may provide enough moral guidance that the problem being disputed can be resolved. They rest, however, on the authority of the groups creating the codes (or on the inherent wisdom of the maxims themselves).

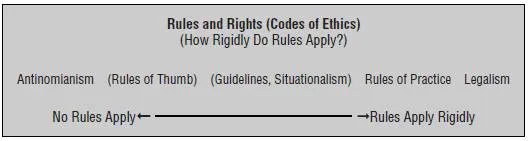

One of the controversies in ethics is how seriously these rules and rights must be taken. At one extreme, an ethical theory could include the view that there are no exceptions to the rules or rights. This view, which almost no one actually holds, is sometimes called legalism. At the other extreme, someone might hold that every case is so unique that no rules or rights can ever be relevant in deciding what one ought to do in a specific situation. This view, which is as implausible as legalism, is called antinomianism. Two intermediate positions are more plausible. Situationalism holds that moral rules are merely “guidelines” or “rules of thumb” that must be evaluated in each situation. The rules of practice view holds that rules specify practices that are morally obligatory. In this view the rules are stringently binding on conduct. Exceptions are made only in very extraordinary circum-stances—much less easily than in the situationalist position. The continuum is represented in Figure 2 and in the more complete map of the ethical terrain inside the front and back covers.

FIGURE 2 Rules and Rights

Normative Ethics

People in an ethics dispute may not be able to determine which rule or rights claim applies or how it should be applied. If the citing of various rules or rights claims cannot resolve the matter at controversy, a more complete ethical analysis may be called for. The parties may have to move to a third level of moral discourse, what can be called the level of normative ethics. It is at this level that the broad, basic norms of behavior and character are discussed. It is in these basic norms that rules and rights claims will be derived and defended. It is also at this level that the norms of good moral character are articulated. The key feature of these norms is that they are general: They apply to a wid...