![]()

1 An introduction to the Pacific Basin

Shane J. Barter and Michael Weiner1

In September 1985, Sakamoto Kazuhiko, a retired Japanese civil servant, set out from his home in Owase, in southern Japan, on his boat, the Kazu Maru. Sadly, Sakamoto was never heard from again. In March 1987, a patrol off the coast of Prince Rupert, Canada spotted a craft floating in the water. It was the Kazu Maru, its captain missing but the boat largely intact. It had travelled over 7,200 km (4,475 miles) along the currents of the Pacific Ocean before arriving in northwestern Canada. Ironically, the small towns of Owase and Prince Rupert had been sister cities since 1968, taking part in a variety of exchanges. Today, the Kazu Maru remains on display in Prince Rupert, restored in cooperation with Japanese officials and the Sakamoto family, a symbol of trans-Pacific ties.

The story of the Kazu Maru is significant for several reasons. It crossed the Pacific Ocean, the largest single geographical entity in the world, along natural currents. Although also home to violent storms, the boat’s voyage lends credence to the ocean’s name, dubbed the “Pacific” by Portuguese explorers due to its peaceful nature. It also helps us to understand how early Polynesians could have left Asia to colonize distant islands as far away as Easter Island, near Chile. Sakamoto’s journey further reinforces an understanding of how oceans can actually connect people, cultures, and countries. We tend to be deceived by the visual unity of landmasses, which are often severed by mountain ranges and political borders. Meanwhile, we tend to see oceans as natural barriers, when in fact oceans tend to connect people and places. There are historical and contemporary reasons to understand human relations in terms of geographical entities such as oceans. Of the 15 countries with GDP in excess of US $1 trillion, 9 are located within or adjacent to the Pacific Basin. Their combined GDP is equivalent to 75 per cent of the global economy, bringing with it trade, migration, cultural exchanges, and common challenges. Thus, the Pacific Basin is essential to our understanding of an increasingly globalized world.

An Introduction to the Pacific Basin provides a multidisciplinary and comparative introduction to an emerging Pacific world. Like the ocean itself, this book connects the diverse peoples of this vast area. In addition to addressing the historical origins and evolution of the Pacific Basin and its sub-regions, the chapters that follow incorporate analyses of colonialism and imperialism, migration and settlement, economic development and trade, international relations, war and memory, environmental policy, urbanization, mental and public health, gender, film, and literature. Rather than attempt to cover all aspects of the historical and contemporary human experience within the Pacific Basin, this textbook explores common challenges and the diverse responses to those challenges. As well as previewing the chapters that follow, this introduction addresses core concepts and questions. First and foremost, what is the Pacific Basin? Next, how do we study the Pacific Basin? Finally, why is it important to study the Pacific Basin?

What is the Pacific Basin?

The Pacific Basin is a geographical grouping of peoples and countries that are proximate to the Pacific Ocean. It follows the “Ring of Fire,” the horseshoe-shaped arc of volcanoes and trenches that extend from New Zealand, through Southeast and East Asia, across Alaska, along the Rocky Mountains, and south through Chile. Within this arc, the Pacific Ocean serves as an ecosystem for numerous animal species. A variety of whales, turtles, and other animals migrate annually across these ocean plains; leatherback turtles, for example, travel 16,000 km (10,000 miles) annually between Australia and Asia, to the coast of Oregon. Thus, the Pacific can be understood as an enormous ecosystem, one that has also shaped human activities for thousands of years.

Comprehending this vast area involves an encounter with overlapping terminology. One common term is the “Pacific Rim,” which emphasizes the edges of the Pacific, not its contents or areas adjacent. One may also encounter references to the “APEC Countries,” economies that are formally part of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, a trans-regional economic grouping that excludes economically weak Pacific Islands and Central American countries, as well as some smaller Asian states. The most popular term, “Asia Pacific,” sometimes written as “Pacific Asia,” refers mostly to eastern Asia (East and Southeast Asia). It is a strange term, since very few countries in eastern Asia actually touch the Pacific Ocean, and if we use “Pacific” loosely, then most of Asia is already Pacific. “Asia Pacific” is also used differently in various contexts, sometimes adding to eastern Asia countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. This more expansive definition is incomplete, overlooking small Oceania countries, Canada, and Latin America, all of which have strong Pacific ties. The Pacific Basin is a broader term than Pacific Rim, APEC, or Asia Pacific, referring to all of the countries bordering the Pacific Ocean as well as those neighboring countries with intimate ties to the Pacific.

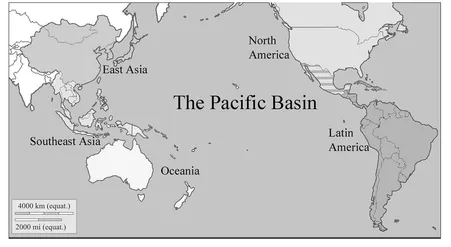

What countries are included in the Pacific Basin? Unlike the Pacific Rim, the Pacific Basin includes the contents of the Pacific, namely Oceania. Strangely, Oceania is often left out of formulations of the Pacific, especially those focused on economic issues, even though it is quintessentially Pacific. For the Pacific Basin, the islands of Oceania are important sites and the challenges faced by their peoples are immensely important. Similarly, while Asia Pacific typically refers to the US, Australia, New Zealand, and East Asia, the Pacific Basin also features Southeast Asia, Oceania, Canada, and Latin America. The Pacific Basin thus includes traditional geographic “areas” of Oceania, Southeast Asia, East Asia, North America, and Latin America. These regions of the Pacific Basin are represented in Figure 1.1. Of course, world areas are contested and fluid. Thus, Papua New Guinea is represented as part of Southeast Asia and Oceania, while Mexico is simultaneously North American and Latin American. One could also include the southwestern US as partially Latin American, or Vietnam as East Asian.

Figure 1.1 Areas of the Pacific Basin

One way to think about the Pacific Basin is as an additional layer on top of more traditional “area studies.” The Pacific Basin is a region of regions, a meta-area of diverse world areas connected by the ocean. The idea of a basin is flexible, allowing the Pacific Basin to include more than just the countries bordering on the Pacific Ocean. Nor is the Pacific Ocean itself an objective reality, separated from the Bering Sea, South China Sea, Gulf of Thailand, Java Sea, and Indian Ocean largely by human imagination. As historian Edward Alpers (2013, 1) observes, “unlike continental land masses, oceanic boundaries are, literally, more fluid.” This makes the more flexible idea of a basin particularly useful. While South Korea and Thailand technically lack Pacific shores, it would be a mistake to exclude these important countries from the Pacific world.

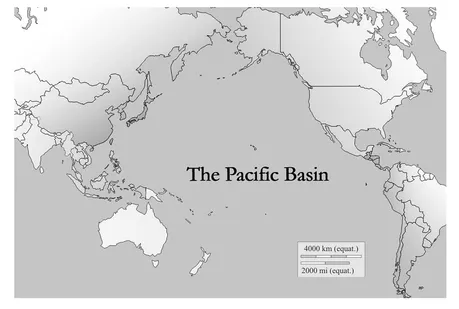

We prefer a “mandala”-type definition, a radial categorization that acknowledges varying degrees of inclusion. The “most Pacific Basin” areas include Pacific Islands, Chile, Japan, and the US—places bordering the Pacific Ocean and home to considerable trans-Pacific migration, investment, and cultural exchanges. As one moves away from the Pacific Ocean, countries become less part of the Pacific Basin, including perhaps Brazil, the Caribbean, Russia, and South Asian countries such as India. One advantage of a mandala approach is that it may also speak to subnational variation. Some parts of China, Canada, the US, and Indonesia are more Pacific than are others. California is more connected to Asia than is Vermont or Minneapolis, just as Hong Kong is more part of the Pacific Basin than Tibet or Inner Mongolia. As a result, Figure 1.2 represents degrees of being part of the Pacific Basin, allowing for subnational variation and explicitly rejecting an “in or out” membership of the Pacific Basin.

Figure 1.2 A radial view of the Pacific Basin

For our purpose, the Pacific Basin is defined loosely by the countries shaped by the hydrography of the Pacific. It includes entire areas, namely Oceania, Southeast Asia, East Asia, North America, and Latin America, but may also extend beyond these areas (thus, some chapters make reference to India and the Caribbean). The value of the Pacific Basin concept also varies within these regions in terms of connectivity to and interaction with the Pacific.

How do we study the Pacific Basin?

There are two broad ways to study the diverse phenomena encompassed within the humanities and social sciences. One is to begin with a subject, developing a disciplinary lens such as history or economics, and then analyze events through related theories. An alternative is to begin with places, developing expertise in specific countries or regions, and then applying disciplinary theories. More or less, we can prioritize subject or place. The former is the world of traditional academic disciplines, while the latter is the world of international and area studies. Academic disciplines such as political science, history, and cultural studies (to name a few) tend to value broad theories, while area studies tend to value accuracy in particular places. These approaches reflect distinct sensibilities, but each possesses great value for generating knowledge of the world. The reality is, of course, more nuanced, as scholars typically specialize in a discipline as well as an area, and together, these sensibilities make for a more informed understanding of the world.

The Pacific Basin is a geographical area, or in actuality, a collection of areas. It is thus connected to international and area studies. Area studies scholars have long worked to ground theories in specific places, seeking to generate insights that fit local contexts and perhaps inform policy. But area studies also suffer from some important shortcomings. Experts in one country or region may lack sufficient knowledge of neighboring areas, artificially severing the places they know from those they do not. This leaves area experts less equipped to understand transnational phenomena or to understand how various issues play out across areas. For example, Mexico specialists may not be equipped to analyze the popularity of Telenovela in China, while Indonesia experts might not fully grasp the importance of East Asian cultural imports, such as K-Pop. Fixed national and area borders are especially problematic in a globalized world and this has led scholars to rethink how we study areas.

One response to the challenges faced by area studies is to reposition areas within broader, geographically defined meta-areas such as the Pacific Basin (Barter 2015). The pioneering work of Fernand Braudel allows us to rethink the concepts of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa by presenting a history of the Mediterranean World. We tend to see continents as distinct places, pretending that Europe, the Middle East, and Asia are not part of the same continent, but Braudel notes that much of human history has taken place through “the plains of the sea,” across which trade, cultural exchanges, and empires were formed (Braudel 1995, 103). By recentering Europe along the Mediterranean Sea, Braudel is able to rethink many aspects of human history as well as contemporary challenges related to migration, security, and trade. This has led many scholars to utilize oceans as units of analysis, providing a way to see places in new ways and to better understand connections between areas. Recent studies have looked at the Indian Ocean (Alpers 2013) as well as the Atlantic (Green and Morgan 2009) as units of historical and contemporary analysis. Studying the Atlantic as an area of human activity allows us to better understand European colonialism, the slave trade, and contemporary trade and security issues. Analyzing human connections across oceans essentially destabilizes area studies, by rethinking traditional area divisions, while prioritizing places over theories.

An Introduction to the Pacific Basin reflects this new avenue of scholarship. As David Igler (2013, 10) writes, studying the Pacific “offers similar analytical payoff to the term ‘Atlantic World’.” It also provides new ways to incorporate both disciplinary and area studies in analysis. Scholars driven more by disciplinary sensibilities must ground their theories in regions, but not specific places as dictated by area studies. Disciplinary research can thus explore phenomena that cut across the Pacific or compare how phenomena vary across regions. For example, political scientists interested in Asia may consider how processes of democratization vary between Southeast Asia and Latin America, while students of literature might draw comparisons between post-colonial novels in Colombia, Indonesia, and South Korea. Meanwhile, the Pacific Basin demands that area specialists take into account the broader regional contexts. Rather than focusing on a single country or area in a vacuum, the lens of the Pacific Basin requires that we consider it in broader, trans-regional contexts. For example, instead of approaching Vietnam as a single case, we can also consider its role in Southeast Asian organizations, influences from China and Japan, relations with the US, and its Californian diaspora. To study the Pacific Basin is thus to embrace multidisciplinary research that is grounded in broad areas. This textbook represents a middle ground, blurring disciplinary and area studies by ratcheting up our units of analysis.

Why the Pacific Basin?

Compared to “what” or “how,” the question of “why” one should study the Pacific Basin may be the easiest to answer. While defining the Pacific Basin or any other regional geographic grouping can be messy, and explaining how we study the Pacific Basin is rather complex, there are clear reasons why the Pacific Basin deserves our attention.

One important reason to study the Pacific is economic development, coupled with a rebalancing of global wealth and trade. Historically, Asia was in many ways the center of the world in terms of technology, culture, and trade. Colonialism was in part an effort by relatively peripheral and backwards Europeans to participate in a global economy dominated by China and India. European colonialism severed pre-existing networks, subordinated both China and India, transferred wealth to Europe, spread Western culture, and incorporated the Americas and Oceania into a new global system. The world was Atlantic-centered for several centuries, with power situated in Europe and then the eastern United States. These relationships have changed in the twenty-first century, and will continue to shift for the foreseeable future. Development in the western Americas has altered dynamics in the Western Hemisphere, with Vancouver, Seattle, Los Angeles, Lima, and Santiago emerging as important “gateway” cities. The Japanese “miracle” of the 1960s was followed by that of the “Asian Tigers”—South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, along with the so-called “Tiger Cubs” of Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. More recently, the dramatic rise of China, as well as Vietnam and India, has led to a global redistribution of wealth and power. For students wanting to understand this ongoing transformation, knowing the Pacific Basin is essential.

The importance of the Pacific goes beyond economic development. The diverse cultures and societies of Asia demand attention in their own right. In recent decades Japan, South Korea, and China have emerged as important global centers of cultural production, while the largest film industry in the world is located in India. Along with the redistribution of global power, including changes in education, migration, travel, and global communications, we see the ongoing development of hybrid cultures. While no one sel...