- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is the first comprehensive introduction and guide to Sweden's most spectacular Stone Age monuments: the dolmens and passage graves, which began to be constructed over 5000 years ago. The introduction provides a detailed social interpretation of these monuments outlining how and why they were built and the ways in which they related to economy and landscape, politics, ceremony, symbolism and belief. This is followed by a systematic regional guide to all the major monuments in Skåne, Halland, Västergotland, Öland and Bohuslän, illustrated by numerous photographs, plans and maps.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Dolmens and Passage Graves of Sweden by Christopher Tilley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Introduction

ONE

Stone Monuments and Prehistoric Societies in Sweden

The dolmens and passage graves of Sweden are some of the most spectacular surviving prehistoric sites in the country. Similar monuments are found throughout coastal areas of Europe from southern Spain to Scandinavia. Those in Sweden mark the terminal north-eastern end of their distribution. Dolmens and passage graves are the earliest stone-built monuments to be built anywhere in Europe. Most of those in Sweden were constructed by the first farming communities, over 5,000 years ago, during a relatively brief period from around 3,600BC to 3,300BC. They were resting places for the dead and ceremonial centres, built towards the end of the early Neolithic and at the beginning of the middle Neolithic or New Stone Age (Table 1.1).

Distribution

Three main types of stone-built monuments occur in Sweden: long dolmens, round dolmens and passage graves. Most of the dolmens are older than the passage graves, although in some areas there is an overlap in the time spans of the construction of the different monument forms. They are found in five areas: Skåne, Halland, Öland, the Falbygden area of Västergötland and Bohuslän (Fig. 1.1).

Table 1.1 Simplified chronological divisions for southern Swedish prehistory.

| Date | Period |

| AD50-400 | Roman Iron Age |

| 500BC-AD50 | Early Iron Age |

| 1000-500BC | Later Bronze Age |

| 1800-1000BC | Earlier Bronze Age |

| 2400-1800BC | Late Neolithic |

| 2700-2400BC | Middle Neolithic (MN) B |

| 3500-2700BC | Middle Neolithic (MN) A |

| 3800-3500BC | Early Neolithic |

| 9000-3800BC | Mesolithic |

The combined period covering the Early Neolithic and MN A phases is also termed the Funnel Neck Beaker Culture, or TRB after the German terminology (Trichterbecher). The MN A phase is traditionally subdivided into five periods: MN I (earliest) to MN V (latest). The MN B phase is characterised by the simultaneous presence in southern Scandinavia of the battleaxe/corded ware culture or tradition, and the pitted ware tradition. Unless stated otherwise in the text, all excavated finds from the dolmens and passage graves are of MN A date.

Figure 1.1 The distribution of dolmens and passage graves in Sweden

In Skåne, 105 documented monuments are located in five fairly compact and distinct subregional groups (Fig. 1.2). Many others must have been totally destroyed but it is impossible to estimate how many. A find of a totally destroyed long dolmen at Hindby Mosse, Malmö (Burenhult 1973b) indicates that a group probably existed in the Malmö area, now completely obliterated by development. In the past these monuments have frequently served as quarries for building stone. Other ploughed down examples are, without doubt, still to be located. We also know of a number of examples of monuments over which later Bronze Age round barrows were constructed (e.g. Hansen 1931: site 34; Jacobsson 1986) and others may still be hidden under the numerous later barrows that occur in Skåne.

The overall distribution, as known at present, is unlikely to be merely the result of differential destruction. Hypothetically we might imagine a situation in which the tombs were originally uniformly spread across Skåne. We would then expect that more tombs would be destroyed in the areas that are densely settled today with most agricultural activity. However, it is in precisely these areas that the tombs are almost solely located. In the less fertile, less densely populated and most boulder rich areas of Skåne, very few tombs are known. Recent exhaustive survey work and use of place name evidence to locate former destroyed monuments in southern Skåne has located 17 possible destroyed monuments (M. Larsson 1988; L. Larsson 1992b: 36).

The degree of regionalisation in the distribution of the monuments in Skåne contrasts with the other areas in which they are found in Sweden. Each of these regional groups contains long dolmens, round dolmens and passage graves. There are roughly equal numbers of passage graves in subregional groups 1-4. Passage graves and dolmens occur in approximately equal frequencies in groups 2, 4 and 5, whereas passage graves dominate in group 1 and long dolmens in group 3. The overall distribution is strongly coastal and riverine, and no differences are apparent between the dolmens and the passage graves in terms of whether either type of monument might be preferentially located closer to the coast.

Figure 1.2 The distribution of dolmens and passage graves in Skåne. Key: 1 Round dolmen; 2: Long dolmen 3: Dolmen chamber without mound; 4: Passage grave; 5: Monument type uncertain. Large numbers indicate subregional groups of monuments

In Halland only 13 certain monuments are known. As in Skåne there are roughly equal numbers of dolmens and passage graves. Here they are also all strung out along the coast and near to river courses, either as isolated sites or in small groups (Fig. 1.3). The distribution of the monuments in Bohuslän is very scattered, with 88 of them situated in a coastal strip 150 km long, with no site further than 5 km from the nearest coastline (Fig. 1.4). Here we probably have a relatively high sample of the total original number since agriculture and development has been considerably less extensive than in Skåne, many of them are not on agricultural land and sources of stone for building other than monuments occurs in abundance. Blomqvist estimates that no more than around ten tombs might have been destroyed (Blomqvist 1989: 13).

Figure 1.3 The distribution of dolmens and passage graves in Halland. Key: 1: Dolmen; 2: Passage grave; 3: Possible megalithic grave

The surviving tombs are found in the inner parts and on the mainland of the rocky coastal archipelago. Roughly half of them are confined to the two islands of Örust and Tjörn. The overall distribution is fragmented such that no degree of regionalisation may be discerned. Round dolmens and passage graves occur in approximately equal numbers, whereas only six long dolmens are known. They are irregularly dispersed across the landscape, the only exception being in the Tegneby area of central Örust, where intersite distances between the monuments tend to be more regular. Otherwise they display a strong tendency to occur either as isolated sites or in groups of up to four, with considerable distances (4-10 km or more) between these groups and the more isolated sites.

Västergötland provides a total contrast with the three other areas that have been discussed. In an area measuring only 38 km north to south and 25 km west to east, at least 265 densely packed passage graves occur (Sahlström 1915a; Hellman 1963; Sjögren 1986; Blomqvist 1989) (Fig. 1.5). They all occur on arable land and many have been badly damaged as a result. Their large numbers and dense concentration suggest that considerable numbers may not have been destroyed. Sixteen are still preserved in gardens and parks within the town area of Falköping, and monuments occur near to churches and barns so may not have been exploited too badly as sources of building stone.

Figure 1.4 The distribution of dolmens and passage graves in Bohuslan. Key: 1: Long dolmen; 2: Destroyed monument or monument of uncertain type. 3: Round dolmen; 4: Passage grave

Figure 1.5 The distribution of passage graves in Västergötland in relation to landscape features. 1: Flat-topped, steep-sided mountain of igneous rock; 2: Marshy areas; 3: Limestone plateau; 4: Passage grave. Letter A marks Ålleberg mountain

Only three possible dolmens have been documented from this area. A clear spatial pattern is evident. In the centre of the distribution the monuments tend to be regularly spaced, occurring in straggling north to south rows with a more irregular spatial dispersion around the fringes where the tombs have the greatest nearest neighbour distances. The overall distribution is virtually continuous from west to east with only small breaks of 3-4 km between groups of tombs along a north-south axis.

Apart from these regions small numbers of monuments have been documented elsewhere in Sweden. Four passage graves occur in a group on western Öland, one possible example is known from Östergötland (Janzon 1984) and another from Gotland (Blomqvist 1989).

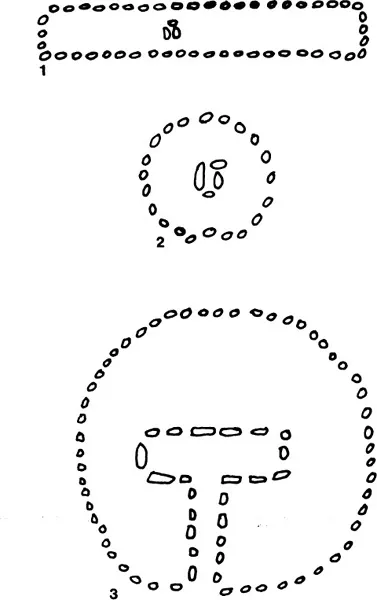

Monument form and techniques of construction

The large stones from which these monuments were built are undressed. That is, they were used in their natural form as found. Their shapes and sizes were, however, carefully selected in the process of building the monuments. The long dolmens consist of a central chamber, or a number of chambers, made up of large stone blocks covered with a single capstone and surrounded by an earthen mound, stone cairn or a mound made up from a mixture of earth and small stones. This mound would have covered the entire chamber with the exception of the capstone, which, in many cases, would have been visible jutting out from it. Around the edge of the mound a rectangular chain of large kerbstones were placed (Fig. 1.6).

It is important to remember that all the long dolmens we see in the field today are ruins. Some, or all, of the kerbstones have been taken away, and the mound damaged or completely or partially removed, leaving in many cases simply a naked chamber. One of the best preserved examples in Sweden is the Haväng dolmen in eastern Skåne. (See Part II: Skåne, site 43; hereafter sites discussed in Part II are referred to in brackets as, for example (S43).) Even here the stone cairn that would have enclosed the chamber has vanished. In Skåne we know of two examples of long dolmens possessing two chambers. Long dolmens with multiple chambers do not occur elsewhere in Sweden, but are fairly frequent in Denmark.

The main difference between the round dolmens and the long dolmens is the shape of the circular mound enclosing the central chamber (Fig. 1.6). The mounds were enclosed by a stone facade, and the single central stone chamber was usually provided with a short entrance passage. The fact that many of the chambers of the long dolmens, and those of the round dolmens, were provided with short (1.5 m or less), unroofed passages links them with the other major class of monuments, the passage graves (Fig. 1.6).

Passage graves generally have a round mound surrounded by kerbstones and a roofed passage of variable length leading to a central chamber of much greater dimensions than those possessed by the dolmens. The number of chamber roofing stones varies from one, in the smaller examples, to eight or more for some of the largest. The Swedish passage graves all occur singly within a mound with the exception of two examples from Skåne, Annehill (S10) and Kungsdösen (S40), in which a single mound encloses two chambers and passages placed side by side.

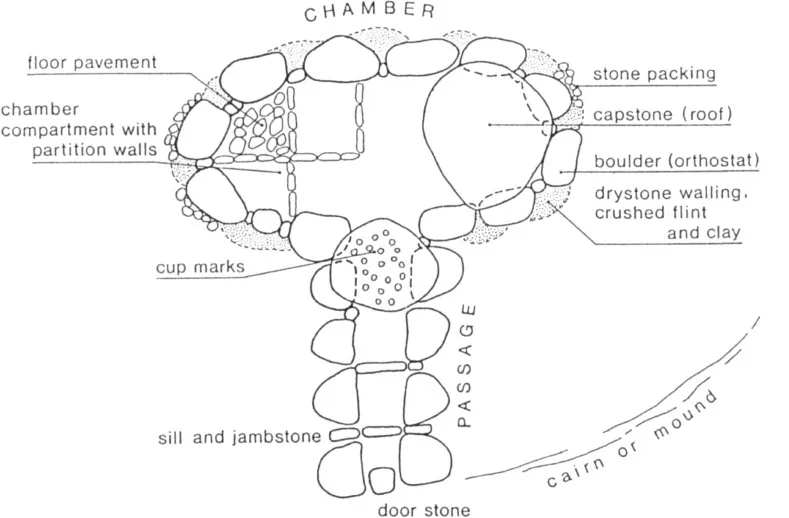

These monuments were constructed with great care and attention to detail and technologically they are rather sophisticated. In general terms a number of distinctive architectural features can be identified in relation to the chambers and passages (Fig. 1.7). Recent excavations have shown that the ancient land surface on which the tombs were built was carefully selected and prepared before tomb construction began. For example, the site of the long dolmen at Säve, Bohuslän (B30) had been burnt off (Hultberg 1979), and the ground underneath the cairn at the Skredsvik round dolmen (B12) had been levelled and cleaned off (Cullberg and Kindgren 1990: 15).

Figure 1.6 Schematic plans of the three main types of monuments in Sweden. 1: Long dolmen; 2: Round dolmen; 3: Passage grave

Figure 1.7 The main constructional elements in a passage grave from Skåne. After Strömberg 1971b

In Skåne, drier and sandier locations were generally chosen to site the tomb (M. Larsson 1988). Tombs were usually located on previously cleared, settled or farmed areas. The Ramshög passage grave in south-east Skåne (S51) was sited on top of an earlier Neolithic settlement area (Strömberg 1971a: 108). Ard, or cultivation marks, occur on the ancient land surfaces under many Danish tombs but are at present unknown in Sweden simply because areas underneath the mounds have been insufficiently investigated.

The stones for the large chamber and passage uprights were probably obtained locally in the immediate vicinity of the tomb. In Skåne they are glacial erratics - boulders deposited during the retreat of the ice sheets - of granite and gneiss. In the Neolithic period there would have been little shortage of such material, which would have been strewn across the landscape. The neat stone-free and boulder-free agricultural fields that we see today would not be found during the Neolithic period. In Bohuslän there is no shortage of loose stone blocks today but those of the form and size used to construct the tombs are comparatively rare. The actual stones used in construction were carefully selected, and the smoother and flatter surfaces were placed so as to form the inner walls of the chambers and passages with the rougher and more irregular surfaces facing outwards.

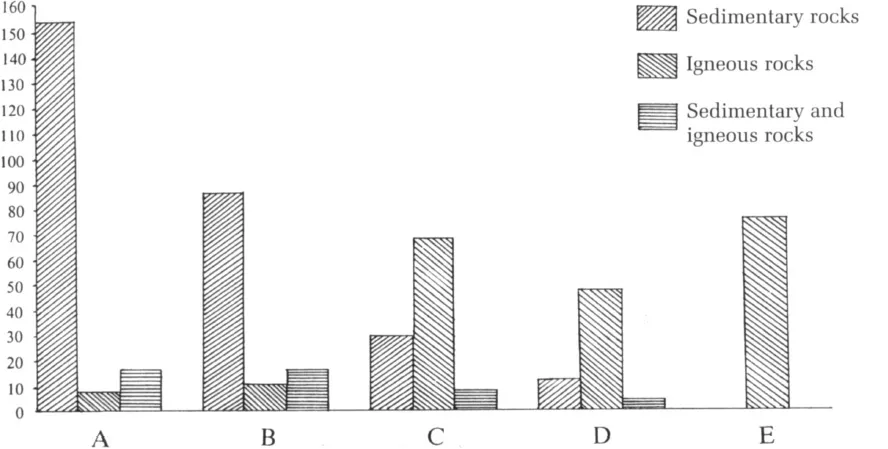

In Västergötland, the tombs were constructed from a wide range of different stone materials, including the sedimentary rocks of the plateau area of Falbygden on which the tombs themselves stand (red limestone and sandstone) and the local igneous rocks (diabase and gneiss) of the nearby table mountains. Figure 1.8 shows the different recorded stones used to build the tombs. As many of them are either partially destroyed, or the stones only partly visible for surface survey, too much emphasis should not be placed on the specific figures but rather to the general trends in the data.

Figure 1.8 Types of stones used to build the passage graves in Västergötland. Key: A: Chamber uprights; B: Passage uprights; C: Chamber roofs; D: Passage roofs; E: Keystone (final passage roofing stone). Source: Tilley 1991

A number of fascinating features emerge. The keystone, or roofing capstone, placed at the point at which the passage enters the chamber, is always of igneous rock (usually diabase). The chamber and passage uprights of the tombs are, in most cases (86 per cent of chamber walls, 83 per cent of passage walls), built solely of the sedimentary rocks on which the tomb itself stands, occasionally with an admixture of igneous rocks (9.6 per cent of chamber walls, 7 per cent of passage walls), while the preferred building stone used to construct the chamber and passage roof is igneous rock. There is, then, a clear preference in terms of the choice of sedimentary rocks for the uprights and igneous rocks for the roofing stones. Even in the few cases in which sedimentary rocks are used for the roof, the keystone is always igneous.

The natural properties of the stone result in the creation of another series of contrasts. The sedimentary rocks split into regular surfaces permitting the creation of standardised and artificial looking chamber and passage walls. By contrast, the igneous roofing stones are irr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- The Maps

- Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: Guide to the Monuments

- Further Reading

- References

- Site Index