eBook - ePub

Teaching without Disruption in the Secondary School

A Practical Approach to Managing Pupil Behaviour

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching without Disruption in the Secondary School

A Practical Approach to Managing Pupil Behaviour

About this book

Behaviour management training of trainee and qualified teachers has been a national priority for some time. This second edition addresses the point that this training and practice should be evidence-based. The importance of adopting a research-based approach is a specific requirement of the guidelines on teacher training and central to this book. The training materials in this book give examples of how to put the research into practice, which in turn makes the text more useful for self-development, trainers in schools and university education departments. Moreover, these materials are supported with case studies showing how they have been used successfully in schools throughout the UK.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Teaching without Disruption in the Secondary School by Roland Chaplain in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Theory, research and behaviour management

Rigorously researching what works best in respect of managing pupil behaviour should be routine in education. Judging the validity of a claim that one approach is better than another should be based on objective empirical research, not what sounds like a good idea. Unfortunately, that is not always the case in reality. Many books on managing behaviour often contain statements like ‘this book avoids dry/boring/complex theory and research’ and go on to say that the book is based on common sense and on the author’s experience as a teacher. Out-of-hand rejection of theory and research in this way demonstrates ignorance of what a theory is. These authors’ collections of anecdotes, good ideas and tips collectively constitute their implicit theory of how to manage behaviour in class. As discussed in Chapter 3, we all have our own implicit theories about a range of phenomena, including intelligence (Blackwell et al., 2007) and personality (Baudson and Preckel, 2013), and we all have theories about behaviour (Geeraert and Yzerbyt, 2007).

‘Practical people’ often believe that ‘the facts’ (i.e. their experience) speak for themselves – but they don’t. Facts are interpreted, and the interpretation relies on implicit theories that go beyond the facts to give them meaning. Despite their limitations, personal theories might work satisfactorily for some people most of the time, but those theories may prove wrong, inappropriate or disastrous for someone else. Should the ‘tip’ you are given not work for you, what do you conclude and what do you do next? Picking up ideas as you go along may work for gardening, but I consider teaching to be a profession, and being professional should include having the particular knowledge and skills necessary to do your job. Just because behaviour management training has had a low profile in teacher education should not mean that the research evidence available about what works best should be ignored.

The term ‘evidence-based practice’, increasingly used in education, means adopting methods based on sound theoretical principles and supported by empirical research. It applies to all areas of pedagogy, including behaviour management as the DfE recommendations for behaviour management training made clear:

Theoretical knowledge: trainees should know about scientific research and developments, and how these can be applied to understanding, managing and changing children’s behaviour.

(DfE, 2012)

Whilst there are a number of established theories, models and frameworks available with contrasting views on how to manage behaviour, I have chosen to focus on those supported by the strongest empirical evidence. If you wish to know more about other models, Porter (2006) provides a useful overview of seven contrasting approaches.

The cognitive-behavioural approaches, models and methods that follow are housed in empirical evidence drawn from educational, psychological and neuroscientific research about behaviour management and wider aspects of human behaviour. Applied correctly, they will provide you with a framework on which to organise your classroom management planning to quickly establish and maintain your authority as a teacher, develop pupils’ engagement with learning, build effective classroom relationships, create the conditions for teaching and learning and help develop pupils’ self-control and social competence.

Behavioural approaches focus solely on observable behaviour, whereas cognitive-behavioural approaches focus on both observable (overt behaviour) and thinking and emotions (covert behaviour). Behavioural approaches change behaviour by reinforcement and/or punishment. Cognitive approaches change the behaviour by changing the thinking (and emotions) behind the behaviour, actively trying to persuade people to think differently. It follows that cognitive-behavioural approaches (CBA) combine the two in different proportions, depending on the specific approach. CBA have been shown to be effective in decreasing disruptive behaviour in the classroom (Sukhodolsky and Scahill, 2012); to improve pupils’ self-control (Feindler et al., 1986) and to have lasting effects (Lochman, 1992).

The following descriptions of the theories and models have been simplified to make them more accessible and usable in the classroom. Numerous references are included throughout the chapter for anyone wishing to develop an in-depth knowledge.

Behavioural approaches (BA)

The basic premise of these approaches is that all behaviour, including unacceptable behaviour, is learned through reinforcement and deterred by punishment. Elements of BA are evident in all schools, where pupils receive rewards (e.g. praise, tokens, or having tea with the head, etc.) for behaving as required or sanctions (e.g. detention) for misbehaving. Unfortunately, in many instances, because the principles underpinning the approach are misunderstood, they are ineffective, or their effectiveness is limited.

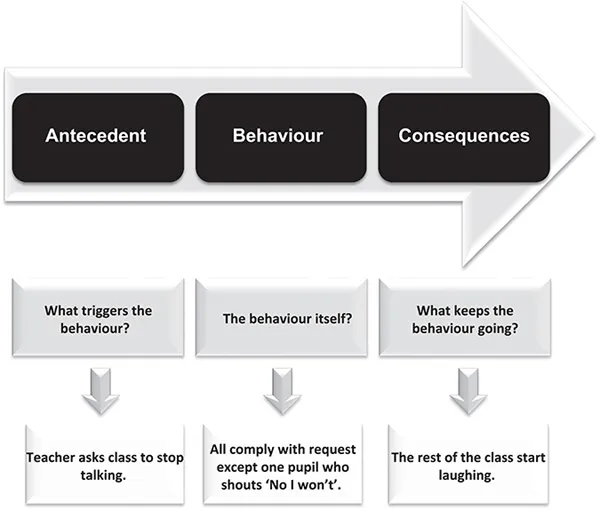

BA offer a scientific approach to behaviour management, since they are based on structured observation, manipulating the environment and measurement of behaviour. There are three areas of focus: what occurs before a behaviour (antecedent) or what starts it off; the behaviour itself; and what follows or keeps it going (consequence), from which a hypothesis is created and tested (see Figure 1.1). For example, Miss Jones has difficulty getting pupils to stop talking so that she can give out instructions. She decides to introduce an incentive for speeding up responses to her request for pupils to stop talking and face her when she claps her hands. She claps her hands (antecedent) and the first five pupils who stop talking immediately (behaviour) receive a sticker (consequence). She repeats this process until satisfied that the routine is established. The objective being for the class to complete the task competently and quickly.

Whilst behaviourists recognise that something goes on inside the brain (covert behaviour), they argue that we can only theorise about what the individual is thinking and how their previous history might have influenced that behaviour. This focus on the measurement of overt behaviour is not limited to behaviourists. Other approaches in psychological and educational research also rely on measuring behaviour to support their theories. Cognitive psychologists might compare time taken to complete a maths task and infer how different metacognitive strategies are advantageous or disadvantageous in problem-solving. Neuroscientists measure performance on a task whilst mapping brain activity using scanning equipment, inferring which brain regions might be associated with specific behaviour.

Figure 1.1 ABC model of behaviour.

Neuroscience has provided information about the effect of rewards, punishment and motivation on brain activity, elements central to the behavioural approach. For example, dopamine, a neurotransmitter, helps control the brain’s reward and pleasure centres, notably through pathways between the limbic system and the forebrain (Thompson, 2000). It also enables individuals to prioritise rewards and to take action to approach them. At the very moment your brain recognizes something it likes (e.g. food), it will make you think it is good and will encode that information and remember that you liked it (Galván, 2013). Research has also demonstrated that the substantial behavioural changes during adolescence are largely believed to be driven by rewards, including monetary, novel and social rewards, and by extension, the reward-sensitive dopamine system (Galván et al., 2006; Van Leijenhorst et al., 2010). This helps explain why, if a teacher picks the right reward and correct rate of rewarding, he/she is able to manipulate behaviour and engagement with learning since it is associated with pleasure and reward. A reward does not need to be present to have an effect, as dopamine can be released in anticipation or triggered by association with a stimulus, e.g. a teacher opening a drawer that contains desirable stickers, which are associated with a particular behaviour.

Competent teachers can make managing pupils (including those others find difficult) look comparatively easy. Teacher A walks into a room and gives a disappointed look at those pupils who are misbehaving, and those pupils all stop talking, sit down and face the front. New teacher B repeats the same behaviour, but the noise continues – begging the question why? There may be a number of possible explanations, one being a lack of association between stimulus (teacher B’s expression) and the required response and/or the consequences of not doing so – an association that needs to be established and reinforced over time to become automatic.

The two most familiar origins of behavioural approaches are classical and operant conditioning.

Classical conditioning

Classical conditioning is the most basic form of associative or automatic learning in which one stimulus brings about a response.

The Nobel Prize winner Ivan Pavlov, known for his research with dogs (and children), is less well-known as being one of the most influential neurophysiologists of his century (Pickehain, 1999). Pavlov believed dogs were hard-wired to salivate in response to food (a natural response), but he trained them to salivate at the sound of a bell (an unnatural response). He noticed that the dogs in the laboratory would begin to salivate in anticipation of food, for example, when an assistant entered the laboratory at feeding time or when they heard the ‘click’ made by the machine that distributed the food – both unnatural responses. So he began ringing a bell at the same time he provided the food to teach an association between the unnatural and natural stimulus. Initially, the bell was a neutral stimulus, i.e. it did not produce a salivary response. However, after repeated pairings between bell and food, the bell in the absence of food provided the trigger for the dogs to salivate. This relationship is known as contiguity – an association between two events that occur closely together in time. Association learning can be observed in all classrooms. Pupils learning to respond in a particular way to unnatural stimuli, e.g. lining up when a bell is rung.

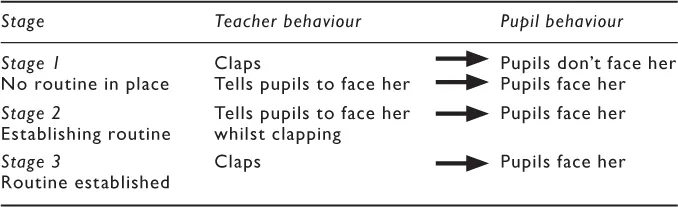

Humans have a distinct advantage over dogs – that is, language, which means that the desired behaviour can initially be stated explicitly – e.g. stand up, sit down, stop talking, or line up – then replaced with more subtle nonverbal triggers such as gestures (e.g. the teacher claps or raises their hand) to initiate the required behaviour (see Table 1.1).

Competent teachers spend the first couple of weeks with a new class establishing routines and teaching their pupils to associate particular cues with specific behavioural requirements in their classrooms (Leinhardt et al., 1987). Trainee teachers taking over classes in which routines are established and efficient can find it daunting, especially if the pupils do not respond to their signals in the same way as they do for the regular teacher. It is essential, therefore, to understand how such behaviours are established and how to develop these routines quickly in order to help a novice teacher feel in control.

Table 1.1 Using classical conditioning to establish a basic routine behaviour

Operant conditioning

The second approach is operant conditioning (OC). The basic premise of OC is that any behaviour that is followed by reinforcement is likely to be repeated. If a pupil blows a raspberry and the class laughs, she is likely to do so again – laughter being the reinforcer. In contrast, behaviour followed by punishment is less likely to be repeated. OC owes much to the work of B.F. Skinner (1974) who explained learning in terms of the relationship between stimulus, response and reinforcement. For Skinner, a stimulus or response should be defined by what it does, rather than how it looks or what it costs; in other words, a functional definition of behaviour. Definitions need not be fixed in advance; a definition can be selected according to what works (Skinner, 1961). OC is a pragmatic approach to specifying behaviour based on a functional definition, meaning that activities should be designed to produce orderly results. For Skinner, the emphasis should always be on positive reinforcement of required behaviour rather than on punishment of undesirable behaviour.

Operant conditioning is used in all schools. For example, verbally supporting a pupil (consequence) for completing a task (behaviour) when asked (stimulus) may increase the likelihood that he/she will continue to make an effort, in order to gain more verbal support. However, this depends on the degree to which a pupil values that consequence. Being praised publicly may not be seen as rewarding by some pupils, who would rather just have a quiet word or a thumbs up from that teacher (Burnett, 2001). Other pupils will not respond to verbal support but will respond to tangible rewards, e.g. stickers. Other pupils are self-reinforcing, in effect they reward themselves for their successes – i.e. they complete tasks because they enjoy it. Put simply, any behaviour that is followed by something that an individual finds pleasurable, is likely to be repeated and becomes learned. Anything that follows a behaviour to keep it going or strengthens it is termed a ‘reinforcer’.

Difficulties in school often result from pupils being inappropriately reinforced for unacceptable behaviour – an action known...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Theory, research and behaviour management

- 2 Stress, coping and well-being

- 3 Teacher thinking and pupil behaviour

- 4 Professional social skills

- 5 Whole-school influences on behaviour management

- 6 Leadership and positive behaviour

- 7 Classroom climate: the physical and socio-psychological environment

- 8 Classroom structures: the role of rules, routines and rituals in behaviour management

- 9 Managing difficult behaviour

- 10 Classroom management planning

- References

- Index