- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For decades, nuclear testing in America's southwest was shrouded in secrecy, with images gradually made public of mushroom clouds blooming over the desert. Now, another nuclear crisis looms over this region: the storage of tens of thousands of tons of nuclear waste. TaintedDesert maps the nuclear landscapes of the US inter-desert southwest, a land sacrificed to the Cold-War arms race and nuclear energy policy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Tainted Desert by Valerie L. Kuletz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

· PART TWO ·

Power, Representation, and Cultural Politics at Yucca Mountain

Yucca Mountain, Nevada

From the U.S. Department of Energy/Yucca Mountain Project

· 5 ·

The View from Yucca Mountain

Perspectives and Boundaries

Mapping the nuclear landscape is a political practice of seeing because it makes visible the unseen inhabitants of deterritorialized—that is, sacrificed—geographies as well as the landscape itself. Part One of this book used spatial coordinates (official and alternative maps and zones of concentrated nuclear activity), and historical and contemporary narratives to foreground the emergent nuclear landscape. Part Two uses similar mapping, spatial, and narrative strategies to illuminate some of the ways different groups in this region view, experience, construct, and organize the Yucca Mountain landscape. Because of the existence in this local region of inequitable positions of power between its different inhabitants, the second half of this book also concerns power relations and how such power relations are developed through cultural narratives about people and place, where different groups with their different knowledge systems meet and vie for legitimacy.

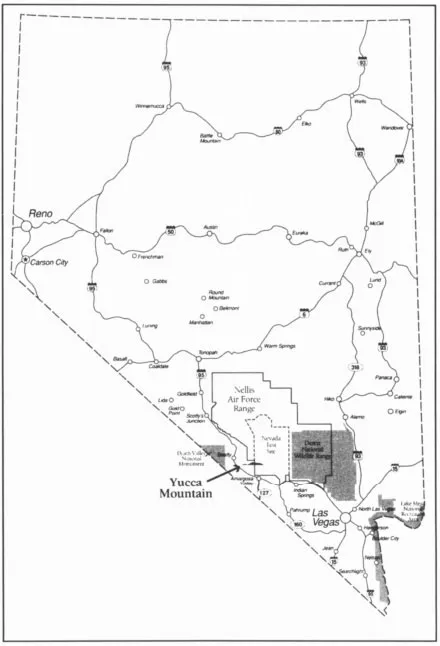

This chapter also introduces the reader to the many perspectives and uses of the Yucca Mountain region—a region organized around and extending outward from the center point of Yucca Mountain. One can travel this area along different narrative and geographic pathways, through both space and time. For instance, traveling from Las Vegas in a northerly direction in a Yucca Mountain Project tour bus, the land can be viewed through the lens of the DOE’s public relations campaign. Or, gathering like gypsy moths around the flame of protest, people can view the land through the lens of antinuclear and Western Shoshone land-rights activists at Cactus Springs or Peace Camp outside the gates of the Nevada Test Site. These protests—which are very near Yucca Mountain—can be reached by car from different directions: from the town of Beatty to the north, from Death Valley to the west, from Pahrump and Las Vegas from the southeast. (You can’t reach the gathering place directly from the east because passage across the Nevada Test Site and Nellis Air Force Range is prohibited.)

Figure 5.1 Yucca Mountain and Nevada

From: The U. S. Department of Energy, DOE’s Yucca Mountain Studies

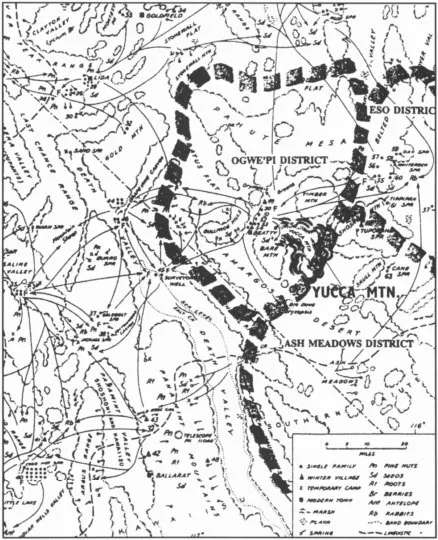

The more discerning observer can peel away the contemporary asphalt-paved roads and recognize that many of these paths preexisted white occupation. Many of the roads follow old Indian passageways that intersected and stretch out across Yucca Mountain. Western Shoshone and Southern Paiute Indians moved across this area from all directions and lived in encampments at different places around the mountain. For instance, just north of present-day Beatty and northwest of Yucca Mountain, Western Shoshone lived in the permanent spring area of Oasis Valley, called the Ogwe’pi district. To the south lay the Western Shoshone and Southern Paiute spring area called the Ash Meadows district. In lower Amargosa Valley, Southern Paiute lived near springs at Pahrump (“Pa” meaning water) and at the Indian Springs/Cane Springs district. The paths that crossed Yucca Mountain itself lead northeast of the mountain to another camping/spring region, in the Belted Range, deep into what is now the Nevada Test Site. This region was called the Eso district and was then inhabited by Western Shoshone.1

Although this is a very dry landscape, clearly it is not, and was not, without water, as the place names of Oasis Valley, Indian Springs, Cane Springs, Ash Meadows, and Pahrump suggest.

This older history of land use is not evident to the average motorist traveling down U.S. 95 en route to Las Vegas. Nor is it generally recognized by the physical and biological scientists studying Yucca Mountain as a possible high-level nuclear waste dump. Nor is it recognized by politicians who need to find a permanent nuclear waste disposal facility outside their home states. The ancient Indian pathways that converge at Yucca Mountain and that organize the space of this region by way of Indian occupation and movement lie beneath the surface of other constructions of space. For the Indians, space here is organized according to these passageways, springs, valleys, and mountain peaks. Yucca Mountain rests between Bare Mountain, Little Skull Mountain, Timber Mountain, Shoshone Mountain, the Belted Range, and Paiute Mesa. From its crest one sees the important spiritual peaks of Mt. Charleston and Telescope Peak—peaks that preside over this terrain like monuments from another time. It rises gently out of the Amargosa Desert to separate Crater Flat from Jackass Flats where rabbit drives were held. Although often dry, the region provides animals for food, wild plants and seeds for seasonal harvests, and many medicinal plants. There is extensive rock art in Fortymile Canyon, as well as camp sites near springs and tinajas. There are also “power rocks” and places where Annual Mourning and other ceremonies were held (such as White Rock Spring, Ammonia Tanks, the Prow Pass). It is a terrain carved out of the earth from “the time when animals were people,” those “beautiful progenitors of present day species”2—when giant snakes moved across the land creating monumental desert washes and coiled up to form mountains. Here, Coyote roamed mischievously across the desert, defining and creating whole ecosystems in his wake.

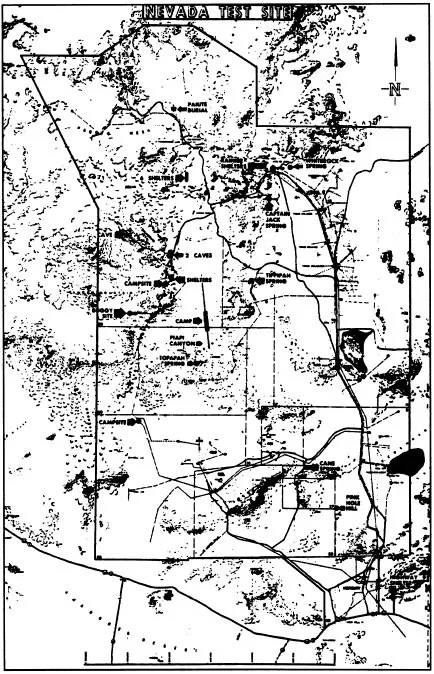

Figure 5.2 Native American use patterns in the Nevada Test Site and Yucca Mountain area

Adapted from: Stoffle et al., Native American Cultural Resource Studies at Yucca Mountain, Nevada (according to Steward 1938)

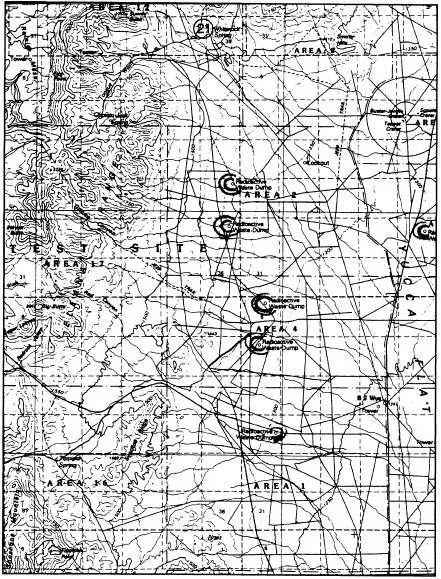

Euroamerican space, on the other hand, is here organized according to a series of highly rationalized, straight, gridlike boundaries imposed from above. For the Department of Energy, Yucca Mountain rests in a square space identified as “Area 25” within a checkerboard of squared-off regions mapped onto the land at the Nevada Test Site. It is the space of the modern industrial state, the organization of what amounts to a periphery inside the core power itself. Military power here blankets the local landscape, disciplining that landscape into a geometry of testing fields. Close examination of archaeological maps dramatically illustrates the layered aspect of cultural occupation, as well as the violence imposed on this landscape by the Department of Energy, in which it identifies numerous radioactive waste dumps scattered across a region that also contains springs held sacred by the Shoshone and Paiute Indians (see figure 5.3). The juxtaposition of military and Indian occupation is made clear when the grid of the Nevada Test Site is superimposed on the map of the shelters, springs, camps, and burial sites of the preexisting Indian population (see figure 5.4).

This highly militarized zone in which Yucca Mountain sits is also a zone of intense scientific study—an outdoor laboratory for different kinds of scientific analysis. Through the scientific perspective, Yucca Mountain gets mapped from the inside out as scientists with the project bore into it removing long cylindrical “cores” that are then tagged, categorized, and studied in order to construct a map, a cross section, of the mountain’s geologic and hydrologic properties.

Figure 5.3 Radioactive waste dumps on the Nevada Test Site

Adapted from: Stoffle et al., Native American Resource Studies at Yucca Mountain, Nevada

Figure 5.4 Springs, shelters, and burial grounds used by Indians at the Nevada Test Site

Adapted from: Stoffle et al., Native American Resource Studies at Yucca Mountain, Nevada (From F.C.V. Worman 1969)

Thus the mountain and its surrounding region can be seen prismatically from many different angles. It can be accessed along different paths. Simultaneously a site of Euroamerican religious and secular protest, a site of Western Shoshone protest, a zone of historical indigenous occupation, travel, ceremony, and origins, and a site of intense scientific study, it also resides on the border of the nation’s nuclear testing fields.

From Ground Level to Mountain Ridge

We’re banking on the natural environment to protect us for 10,000 years!

—DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY TOUR GUIDE explaining why the DOE wants to use a deep-geologic tomb for high-level nuclear waste

At first glance, Nevada’s Amargosa Valley (where Yucca Mountain resides) at the intersection of the Great Basin and Mojave deserts, seems only a sea of creosote and range after range of (apparently) treeless mountains. Although it can be reached from other directions, Yucca Mountain is mostly reached by a road that begins in Las Vegas, from which the Department of Energy offers monthly tours of the mountain. These public relations events sport everything from plush air-conditioned buses, equipped with television monitors playing videos about the Yucca Mountain Project, to a free lunch. The lunch has since been discontinued because of complaints that the DOE was trying to unduly influence public opinion.

Beginning from Las Vegas, the tour moves north toward the mountains as the city fades into new and endlessly expanding pink and beige housing tracts. The DOE guide points out the Southern Paiute Reservation, sacred Mt. Charleston (called Nuvagantu) in the Spring Mountains (mythological site of Southern Paiute origins), Indian Springs with its government gunnery range, then the boundary to the Nevada Test Site, and even “Cherry Patch Ranch,” the brothel servicing the surrounding (mostly military) community. When the tour bus finally turns off the highway and moves northeast toward Yucca Mountain, the feeling of desolation increases as the bus passes through check points where fatigue-clad military personnel board the bus to check for forbidden cameras, recording devices, and weapons. Radiation-monitoring tags clipped onto shirts serve as an additional reminder of the tight security at the Nevada Test Site. A guide informs tourists that they can write to the Department of Energy “in a month or so” to find out if they’ve actually been irradiated.

The expanse of heat-pounded scrub and hot barren sand is interrupted by signs of abandoned MX Missile construction sites (an attempt to make this region the sacrificial target for Soviet nuclear missiles) and buildings of a disbanded nuclear powered rocket program.3 But the surrounding desert mountains possess the ability to transform space, or one’s experience of space. The top of Yucca Mountain alters ones perception of the desert region from what it was on the road leading up to it. Stretched out below the crest of the mountain lies an immense desert floor fanning out in all directions. Yucca Mountain is part of many other mountains—multiple ranges of different colors that form a terrane geography of arcs, circles, and lines that at once define and emerge from the earth’s softer plane of intersecting valleys. Gentle hues of pink, blue, violet, gray, sandy brown, and vermilion blend almost imperceptibly beneath an all-encompassing vaulted dome of blue sky. Ancient red volcanic cones rise up and out from the desert floor like prehistoric anthills. The wind is strong, and everywhere there is the monumental presence of rock.

Puha (Power) and Prometheus

Yucca Mountain may be comparatively small, but it is a powerful place nonetheless. The Western Shoshone and Southern Paiute Indians call the power such places possess Puha because the mountain, like all things Euroamericans call “inanimate,” possesses energy, vitality, life force.4 Space, and the different elements within it, are articulated by Puha, which resides dispersed throughout the landscape. For the Western Shoshone, Yucca Mountain also forms part of the large expanse of desert, valleys, and mountains called Newe Sogobia, “Mother Earth,” land of their origins. The Southern Paiute see the mountain as a place of power in another way as well. According to Richard Arnold (the Indian representative for the Yucca Mountain Project), Southern Paiutes cross over Yucca Mountain at death in their journey to the afterlife.5 Indeed mountain peaks for both the Shoshone and Paiute are “sites of human creation, the points from which humans emerged [out of the womblike regenerative earth] and were dispersed.”6 Separating the northern and southern portions of Yucca Mountain is the Prow formation (so called because it resembles the prow of a ship), historically used for religious ceremonies and Indian gatherings, and recognized by archaeologists with Native guidance as a very powerful and important site.

The mountain has power also because it is high—a point of intersection between earth and sky. Along its back you feel wind energy and the sun. Although it’s not as high as some of the surrounding peaks, it cleaves in upon itself in a series of washes—Fortymile Wash, Dune Wash, and others—which previous generations of Indians used to hunt game, gather edible and medicinal plants, and used as passageways to important springs. Partly because of the severity of this landscape, access to food and water is vital, taking on spiritual significance. Thus, Yucca Mountain was an important passage way on many levels. For the present-day observer, as with the Indians of the past, the mountaintop vantage point offers a “superhuman” view of space from which other significant sites from all directions in the landscape can be viewed.

Yucca Mountain is also powerful because it is the site of so much activity. At the foot of the mountain—out of sight from the summit—hundreds of men scurry about a monumental hole drilled into its side. Reduced to miniature proportions by the size of the tunnel, from a distance they look like ants. The hole in the mountain will hold the most toxic, lethal waste known to humanity. Watching this scene, one can’t help but contemplate the compulsion to produce more and more power, the splitting of the atom, the transformation of Puha into “energy.” The mountain seems to be all about power: the power of place, political power, military and economic power, and nuclear power.

The titanic scale of the tunnel and the reason for its existence also bring to mind the myth of Prometheus—only this time it’s nuclear power that is the (unnatural) fire stolen from the gods. In the myth, Prometheus’s punishment for stealing the fire is, of course, to endure having his liver—that toxin-cleansing organ—forever devoured by birds of prey. Just as Prometheus endures this ravaging virtually forever, so too does the specter of nuclear waste haunt the future. Prometheus and Puha each, in their way, offer radically different perceptions of power: Puha as life force, intrinsic and dispersed throughout the natural world; Prometheus’s power, external, stolen, and ultimately self-destructive.

Compared to the view of nuclear landscapes through time and space in Part One of this book, the view from Yucca Mountain seems small. But because of its centrality in the nuclear-waste crisis, because of its prominence as an object of scientific study, and because of its location within both a sacred landscape and a sacrificial landscape (the Nevada Test Site), it is an important site within the nuclear landscape upon which to dwell. A lot of hopes and fears rest on this small mountain, too. The many people—mostly Indians, scientists, activists, and concerned Nevadans—who have converged on this site, sometimes pursuing conflicting interests, add to a sense of the mountain’s power and make it a fit subject for a case study of how the nuclear landscape is defined and by whom.

The Yucca Mountain region is spatially organized by geographic boundaries, political boundaries, and cultural boundaries. It is also conceptually organized by Euroamericans within a hierarchy of disciplinary boundaries (which affect how the mountain gets identified and therefore designated for use as a waste dump). For Native Americans it is organized by a geography of past and contemporary use, as well as within a web of cosmological boundaries articulated in historical and mythological stories. Differently situated people see things differently and move through this region in different ways, as the example of Puha demonstrates. To ignore the culturally layered nature of this geographic region is to miss a great deal of its richness as a place of power.

From a geopolitical perspective, Yucca Mountain exists within a militarized, federally managed frame of reference, partly within land controlled by the Bureau...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations/Maps

- Legend of Map Symbols

- List of Acronyms

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- ONE: Mapping the Nuclear Landscape

- TWO: Power, Representation, and Cultural Politics at Yucca Mountain

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index