- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Ballooning, like the Enlightenment, was a Europe-wide movement and a massive cultural phenomenon. Lynn argues that in order to understand the importance of science during the age of the Enlightenment and Atlantic revolutions, it is crucial to explain how and why ballooning entered and stayed in the public consciousness.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sublime Invention by Michael R Lynn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 THE EMERGENCE OF AERONAUTICS

Historians have recounted the story of ballooning many times, in many different ways, geared towards a variety of audiences. Most of these accounts take the long view and aim to move from 1783 to the present (or at least to the birth of modern aviation), often utilizing an international approach although occasionally concentrating on a particular country or region.1 On the other hand, a number of historians have explored ballooning from a more biographical approach. While occasionally this means a study of figures such as Pilâtre de Rozier, Lunardi, Tytler or Garnerin, most often the subject of these studies are the Montgolfier brothers, Etienne and Joseph.2 The historiography of ballooning, then, typically proposes its subject as an important invention and key precursor to modern flight, as an analysis of a particular nation’s or region’s involvement in this endeavour, or as an explication of some of those individuals involved in its early practice.

The version of this history here, on the other hand, neither attempts completeness nor limits itself to particular locations or people. While some chronological description appears, this narrative does not want simply to describe the flow of events. Instead, this chapter highlights certain themes in an effort to demonstrate the elements of ballooning that helped account for its popularity and suggest how and why aeronautics spread across Europe. In other words, rather than offer an internal account of the growth and development of ballooning as a particular type of technology, this chapter sketches an outline of ballooning based on what the general public at the end of the eighteenth century might have found important. Since the overall argument of this book hinges on popular attitudes toward ballooning, it becomes important to highlight those aspects of this new invention that dominated the public imagination. The first section provides a description of flight as conceived prior to the invention of balloons. This is followed by an analysis of the geography of ballooning activities and a discussion of the ways in which ballooning spread during the initial years of flight. The public always lauded the first people to fly in a particular region, the first to cross a particular barrier, the first women aeronauts, the highest or longest flights and so on. Enthusiasm for ballooning extolled, in part, the heroic aspect of flights. Ballooning, however, was also dangerous and the next section explores the public fascination with balloon-related accidents and deaths. Last, the appearance of parachuting is discussed, both as a response to the dangers of aeronautics as well as a method for enhancing the entertainment value of ballooning.

Preflight

What’s the news of the day,

Good neighbour, I pray?

They say the balloon

Is gone up to the moon!3

Tales of flight are as old as humanity. The gods of Greek and Roman mythology frequently flew, either in the guise of animals or through their own volition. Unsurprisingly, early Greek and Roman thinkers also turned their attention to the art of flying. Archytas, a Pythagorean philosopher and mathematician living at the time of Plato, reputedly crafted a wooden model of a dove that could fly.4 From antiquity to the age of Enlightenment, numerous authors and savants posited the possibility of flight, sometimes in fictional form and other times with more serious suggestions for how to achieve air travel. Thus, in the decades and centuries before 1783, the general population already had a wealth of competing visions of flight.

Numerous authors speculated about the possibility of human flight in the period before the Montgolfier brothers demonstrated their invention.5 These include flight as a peripheral notion in a larger work as well as books in which flight provided a convenient device for travelling to distant lands (or even to stars, moons and planets). Cyrano de Bergerac, for example, attached bottles of dew to himself; when heated, he claimed, the dew would vaporize and rise up. This allowed Cyrano to jump all the way to the sun and moon. Travelling that far enabled him to discuss social and philosophical problems from a geographical and critical distance.6 Such fanciful descriptions abounded in the eighteenth century including Voltaire’s Micromégas and less well-known books such as Joseph Galien’s L’Art de naviguer dans les airs or Domingo Gonsales’s The Man in the Moone: Or, a Discourse of a Voyage Thither.7 Galien’s book outlines an enormous, impossibly large, lighter-than-air craft designed to transport a military force into the middle of Africa. Gonsales, on the other hand, uses his machine as a means of escape and travel. The frontispiece illustrates his method; birds are harnessed to a frame with a sail on one end and a seat for the voyager.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in Le Nouveau Dédale, suggested the use of compressed air, judiciously released, would, along with a rudder, allow someone to fly through the air.8 Restif de la Bretonne goes back to the idea of human wings in his book, La Découverte australe.9 In his novel The History of Rasselas, Samuel Johnson included a brief chapter, ‘A Dissertation on the Art of Flying’, in which an artist labours to create wings for himself and then tries to use them to fly, only to fall in the water and nearly drown.10 Earlier, in an issue of the Rambler, Johnson wrote about a savant who claimed to have ‘twice dislocated my limbs, and once fractured my skull in essaying to fly’.11 The list of authors who utilized some sort of flight could go on almost indefinitely and includes Jonathan Swift, Aphra Behn and Daniel Defoe, to name just a few.12

Writers of fiction received inspiration for their flights of fancy in the efforts of a number of innovators who tried to launch aircraft of various kinds in the period before 1783. Some savants explored the possibilities of flight with early versions of helicopters. Most famously, Leonardo da Vinci sketched a helicopter in his notebooks. Similarly, Athanasius Kircher worked on the idea of creating a flying machine.13 These individuals belonged to a much longer tradition that continued up to and after the invention of ballooning. The seventeenth-century Italian savant Tito Livio Burattini left Venice for the Polish court to work for King Wladislas IV as a mathematician and Master of the Mint. While there, he developed designs for a ‘flying dragon,’ a heavier-than-air machine with a series of eight pairs of wings that flapped to provide life and forward motion.14 Burattini’s contemporary Chrsitaan Huygens heard news of Burattini’s device and worked on a version of his own which utilized a sort of propeller for propulsion.15 The Jesuit scholar Francesco Lana sketched a model for a flying vessel modelled on a sailboat. In 1709 a Portuguese savant named Bartholomeu Lourenço de Gusmao purportedly created and demonstrated a flying machine. This event, oft-reported after the advent of the ballooning age, remained unsubstantiated. David Bourgeois, for example, discusses it briefly in his 1784 book Recherches sur l’art de voler. Here Bourgeois lists every account of flying he could identify in the period before 1783. He starts with Dedalaus and Archytas but also includes Roger Bacon, Da Vinci, Kircher and Gusmao. In all he mentions over thirty people who engaged with the problem of flight.16 Later, in 1784 the mechanic and scientific popularizer François Bienvenu along with his partner, a naturalist named Launoy, published a short prospectus announcing their flying machine, a sort of early helicopter.17

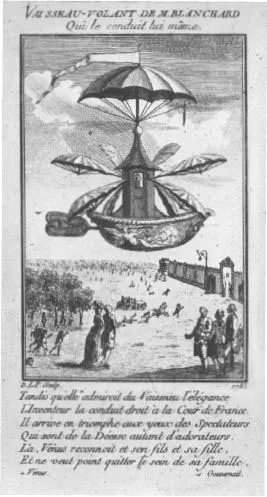

Prior to the invention of lighter-than-air flight, however, other savants struggled with success and lost. Jean-Pierre Blanchard developed what he called a ‘vaisseau volant’, or flying vessel based on one of his earlier inventions, a prototype for a bicycle called a velocipede.18 He began touting his vessel as early as 1781 in an attempt to gain attention, notoriety and funding.19 Although poorly educated, Blanchard exhibited enormous talents as a mechanic. The ‘vaisseau volant’ used foot pedals as well as hand levers to operate four wings. These wings flapped and, in theory, would elevate the operator who sat enclosed in a cockpit. The result, if it had worked, would have been something like a helicopter in design (see Figure 1.1). Blanchard, who claimed his machine could travel at speeds up to seventy-five miles per hour, announced a demonstration in May 1782.20 He planned the experiment for a Sunday and sold tickets to interested individuals. After his first announcement Blanchard published a letter in the Journal de Paris in which he claimed to have received ‘eleven or twelve hundred letters’ about his experiment; this enthusiasm prompted him to add a second demonstration.21 A few days later, however, Blanchard somewhat ruefully admitted he had to delay his spectacle for three weeks during which time he would ‘perfect it’.22

Figure 1.1

Meanwhile, some savants took the opportunity of critiquing Blanchard before he even tried to get his machine off the ground. The celebrated astronomer Jérome-Joseph Lalande, for example, compared Blanchard to the infamous dowser Barthelemy Bléton and scolded the editors of the Journal de Paris.23 He claimed they discussed such absurdities so often that their readers might be convinced the editors believed in any and all nonsense. Later, during the French Revolution, Lalande softened his attitude toward Blanchard and participated in some balloon flights with him during which Lalande conducted meteorological experiments.

Other authors wrote more favourably about Blanchard’s machine. An engineer and engraver named Martinet, for example, wrote a letter to the Journal de Paris in which he claimed Blanchard had performed ‘a little experiment’, and attested to Blanchard’s efforts in order to ‘arrest the cloud of sarcasms which cover it daily with jealousy and incredulity.’24 Unfortunately, at least for Martinet and Blanchard, the ‘vaisseau volant’ was destined to stay on the ground. When the time came to finally stage a launch Blanchard claimed the rain interfered with the efficacy of his machine and instead chose to read a paper about the device.25 Arguably Blanchard’s machine had a fighting chance of getting off the ground; other attempts at flight appeared doomed right from the start. The Marquis de Bacqueville, for example, built a pair of wings and, in 1742, leapt off the roof of his house. Luckily, his home was located alongside the Seine River in Paris. This was ideal in his mind since, if his experiment failed, he would fall into the water. Unfortunately, when this eighteenth-century Icarus fell, he landed on the deck of a washer-woman’s boat and broke his leg.26

The Advent and Geographical Expansion of Ballooning

A full discussion of every example prior to 1783 where an individual wrote a fictional account of flying or, perhaps, actually attempted to take to the skies, could occupy an entire book by itself. So, too, could a discussion of the origins and spread of ballooning; a number of scholars have undertaken to provide just such a narrative account of aeronautics. As noted above, however, it is not the purpose here to rewrite that narrative or to attempt to discuss in full every balloonist in Europe from 1783 to 1820. Instead, this section couples a brief description of the birth of the ballooning phenomenon with an analysis of the spread of this new science throughout Europe and the Americas.

Although, and not without justification, the Montgolfier brothers receive the lion’s share of the attention from scholars narrating the origins of flight in Europe, the broader picture includes a larger cast of characters all working independently towards the same object. Joseph Black, for example, experimented with Henry Cavendish’s new hydrogen gas. In particular, he tried to fill various bladders to see if they might float. The bladders, however, were either too porous or too heavy and his experiments failed. After the Montgolfier brothers launched their first balloon, Black did not argue for a prior claim to the invention although others, like Jean-Pierre Blanchard, did.27 Some savants, like Joseph Priestley and Tiberius Cavallo, also experimented with hydrogen. Thus, the geography of the invention of ballooning extends beyond a single day in Annonay, France. Even the choice made by the Montgolfier brothers, to conduct their first public launch on 5 June 1783, had less to do with the timing of their invention than it did with the convenience of having the appropriate audience present for the experiment. The Montgolfiers had certainly launched balloons, in private, prior to 5 June. However, the moment of revelation was just as important as the moment of discovery and, in this case, Joseph and Etienne felt the necessity of an audience which included local notables so that their experiment might gain in status.28

As the moment and place of invention for ballooning really encapsulates a much larger period of time and place than simply 5 June 1783 in Annonay, France, so too the spread of ballooning cannot be traced in a linear fashion. Instead, the spread of ballooning needs to be seen as a function of the dissemination of information at the end of the Enlightenment, particularly through the periodical press, correspondence and treatises.29 In addition, this new invention needs to be viewed alongside the ability of specific individuals to interpret what they read and recreate the globe. In other words, people in a specific area needed to have access to the right sources of information, and the mechanical know-how to construct a balloon, along with the willingness to risk their reputations, if not their lives, for the sake of aeronautics. Some authors attempted to track this movement across Europe. Tiberius Cavallo, for example, traced the rapid spread of aeronautics although his focus is largely on France and Great Britain.30

The first and easiest illustration of this sort of geographical movement comes with the spread of knowledge about balloons from Annonay to Paris. As the Montgolfier brothers intended, information about their experiment raced to the capital with great speed as news of their success travelled north. Famously, Jacques-Alexandre-César Charles and Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier jumped on the aeronautic bandwagon and conducted experiments of their own, using hydrogen and hot air respectively. Similarly, on 11 September 1783 the Baron de Beaumanoir launched small balloons, a foot and a half in diameter, from ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- 1 The Emergence of Aeronautics

- 2 The Enlightenment and the Utility of Ballooning

- 3 Balloonists and their Audience

- 4 Controlling the Skies: States and Balloons

- 5 Consuming Balloons

- 6 Balloons Inspiring Consumption

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index