eBook - ePub

Chinese Rural Development: The Great Transformation

The Great Transformation

William L. Parish

This is a test

Share book

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Chinese Rural Development: The Great Transformation

The Great Transformation

William L. Parish

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This text examines the Pacific War, the Korean War and the Vietnam War, from the perspective of those who fought the wars and lived through them. The relationship between history and memory informs the book, and each war is relocated in the historical and cultural experiences of Asian countries.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Chinese Rural Development: The Great Transformation an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Chinese Rural Development: The Great Transformation by William L. Parish in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Commerce Général. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Historical Background and Current Issues

William L. Parish

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Chinese agriculture underwent a remarkable transformation. Peasants were given many new incentives to increase production, ranging from increased prices for their products, to more freedom to plant what they themselves found most profitable, to a new emphasis on private, family farming instead of joint, collective farming.

With these changes came a tremendous spurt in production and income. In the four years following 1978, peasant income about doubled. This was in marked contrast to the modest growth rate of the previous thirty years. Equally important, many peasants were lifted out of poverty. In 1978, one-third of all peasants had per capita incomes below one hundred yuan, but four years later only 3 percent had incomes this low.1 These changes have been celebrated in the Chinese press and have become increasingly well known around the world.

Not all the trends were favorable. Abandoning much of the collective organization of agriculture that had been adopted in the mid 1950s weakened some of the social and economic services provided in the intervening twenty years. In some places, the new emphasis on family farming reduced the amount of labor and funds available for public infrastructure activities such as larger waterworks and larger agricultural machines. Social services were also weakened, with fewer villages supporting cooperative medical services or local schools. Income disparities increased in some villages, leading to jealousy of those families who did better and sometimes expropriation of their new-found riches until outside governmental bodies stepped in. Birth control became problematic as peasants calculated that they could prosper with more sons even if denied the increasingly less important collective rations. With fewer collective claims over individuals, illicit migration to cities became more difficult to control. These sorts of dysfunctions, even if not widespread, provided potential ammunition for domestic critics of the new policies.

It is difficult to disentangle the positive and negative consequences of the last few years. Needless to say, the official press tends to mention the negative consequences only obliquely while trumpeting loudly the many positive consequences. It is also difficult to disentangle the causes of changes that are fully reported in the press. Because so many changes in policy were introduced so rapidly, ranging from price changes to more individual family farming, weighing the influence of each policy is difficult.

Fortunately, we can get around some of these difficulties because of the remarkable openness of Chinese villages to foreign scholars during the initial years of these policy changes. This openness included not only a new outpouring of statistics on villages but also permission for a limited number of scholars to live and conduct research in villages. The results of much of this unusual research are captured in this volume.

The scholars writing here do emphasize many of the positive effects of the focus on private, family types of farming (part 2). But they also note the many other kinds of policy changes that were necessary and will continue to be necessary for increased prosperity in Chinese agriculture (part 1). Finally, they note the positive as well as negative social consequences that flowed from earlier collective policies (part 3). In short, written by scholars with firsthand experience in Chinese villages and with new Chinese statistics, this volume provides a comprehensive assessment of where Chinese collective agriculture has been, the forces that led to recent changes, and the problems that Chinese agriculture will continue to face in the future.

Historical Developments

In the enthusiasm for rapid agricultural development since 1978, there is a tendency to forget the progress made in earlier years. In comparative, historical perspective, China's former experiment with collective agriculture may well continue to be judged as relatively successful. As new collectives were formed in the middle 1950s, many of the earlier mistakes of collective farming in the Soviet Union were avoided, and production continued to rise. This occurred in part because of the stepwise mobilization techniques that had been learned in the pre-1949 revolutionary war—peasants were not mobilized immediately into collectives but were taken first through land reform, small mutual aid teams, and then larger and larger collectives. Because the revolution had been a rural one, there was an ample rural leadership to help carry out these changes.

Perhaps most important, certain compromises were made with the existing natural social order in the countryside. Except for a three-year interregnum in the 1958-1961 Great Leap Forward, the basic production and income-sharing unit remained a group of twenty-five to thirty neighbors in the same village. Often these neighbors were close kinsmen as well. They were led not by an outsider sent in by the state but by a fellow neighbor who was paid out of their own farm receipts. Collective farmers kept 5-10 percent of the land for private vegetable plots, as well as family pigs and other sources of private income, totalling about one-fourth of all rural income. They also kept their own houses. More radical leaders were never very happy with these compromises, and there was frequent pressure to eliminate them by increasing the size of the collective unit, increasing collective pig production, limiting private income, and so forth. But the compromise more or less stuck through the 1970s, causing Chinese collective agriculture to be more family- and community-like than otherwise, and perhaps making it more palatable than in some other societies.

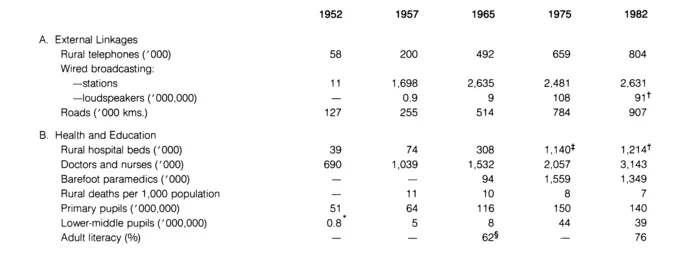

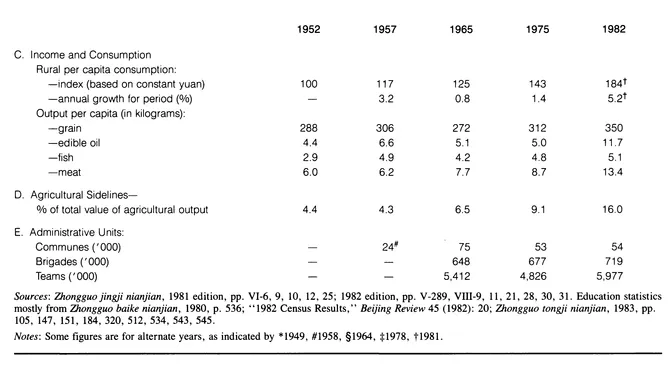

These compromises and the extensive rural administrative network helped produce significant progress on some dimensions. By standard development indicators, dramatic progress was made in the first twenty years of Chinese socialist agriculture. This was particularly true in the creation of an infrastructure that would support further development. A whole panoply of marketing and supply coops, agricultural machinery stations, hardware stores, repair shops, banks, credit coops, schools, hospitals, and clinics was created to serve peasants. In this volume, Marc Blecher describes many of these institutions in one particularly well-developed county. Also, statistics on linkages with the outside world help suggest the degree to which the larger state had entered the countryside. By 1975, virtually every rural brigade had a telephone. There were more than two wired loudspeakers for every team. Roads motorable by bus and truck extended deep into the countryside (table 1.1, panels A and E). Other statistics give a similar indication of progress. By 1979, for example, 87 percent of all commune seats and 63 percent of all brigades had electricity.

There was similar progress in the health and education fields (table 1.1, panel B). Between 1965 and 1975, with more emphasis on rural health care, the number of medical personnel and hospital beds increased rapidly. The number of university-trained Western-style medical doctors stagnated between 1965 and 1975, but the training of all other personnel including secondary-school-trained Western-style doctors, traditional-style Chinese doctors, and nurses as well as barefoot

Table 1.1 Social Change Indicators by Year

paramedics continued at a fast pace. As a result of this training, China came to have more professional doctors, nurses, and hospital beds than virtually any country near its level of economic development.2 With barefoot paramedics and others helping to educate villagers about sanitation, the death rate declined steadily. Thus, compared both to their own past and to farmers in other developing societies, Chinese farmers were more likely to live long lives in which they would be healthy, fulltime laborers.

Not only were farmers healthier, they were also much better educated and prepared to absorb new technological changes that might be introduced in agriculture. By the mid-1970s 93 percent of all school-age children were said to be in school. And because of a push to create new two-year lower-middle schools, many were going on for a year or two beyond the five-year primary school as well. As a result of this educational expansion, over 70 percent of all adults were literate by the mid-1970s. As with health, this level of education is unusually high for a country at China's level of economic development.3

Despite the very real advances in communication, transportation, health, education, and other areas, there was considerable malaise in villages in the mid-1970s. One reason was that although income in 1975 was higher than two decades earlier, the progress over time had been rather slow (table 1.1, panel C). After the Great Leap, Chinese farmers did not return to 1957 consumption levels until almost 1965. Income growth in the late 1960s was respectable, but in the 1970s income again stagnated—the per capita income distributed by the collective was about the same in 1977 as it had been in 1971.4 Consumption of many basic commodities stagnated as well. Grain availability per capita was only about what it had been two decades earlier, and the same was true of fish and other aquatic products. There was less cooking oil than before, for oil-bearing crops had fallen before the onslaught of the self-sufficiency, grain-first policy of the 1970s. The increasing supply of pork, beef, and mutton only partially compensated for the failure of these other goods to increase. In addition, as Mark Selden and Nick Lardy explain in this volume, significant poverty pockets remained. In 1977, almost one-fourth of China's 2,100 counties received per capita incomes below the poverty level of fifty yuan per capita.

There was little chance to mend these sorts of lingering problems until the moderate leaders who had taken over after Mao Zedong's death in 1976 consolidated their power. But when they did begin to see to these problems, they did so in a sweeping manner. In a set of new policies ratified at the December 1978 Third Plenum of the Eleventh Party Congress and then elaborated in the succeeding three years, virtually every aspect of rural organization was transformed. Prices for agricultural goods were raised, villagers got to plant more high-income commercial crops, farmland was partitioned out to families, some peasants left field agriculture entirely, and starting in 1984 party control over communes began to be replaced by economic managerial control over townships.

From this list, it is tempting to focus on the move toward family farming, and to conclude that China's experience with agriculture once again shows how the private family farm is superior to larger, collective units. It is the argument of this volume that this is too simple a view—that many of the lingering problems in Chinese agriculture in the middle-1970s had to do not with the micro-incentives of family versus collective farming but with more macro-issues of government planning and administrative strategies concerning agricultural investment, pricing, loans, and the like. This volume thus begins with these issues, analyzed by economists who examine statistics based on more than a single village. This order of presentation also coincides with how these changes were introduced in China—the macro-level planning and administrative strategies were emphasized in 1978 while the most dramatic micro-level incentive changes began after 1980.

Planning and Administrative Strategies

The question of proper macro-incentives involves the long-debated issue of the proper role of government in economic growth. The Chinese experience over the last three decades provides examples of both constructive and destructive government intervention.

The current literature on proper modes of government intervention remains mixed. Some authors call for an active government role in building rural infrastructure, including research stations, extension services, water control works, marketing, and other support services that benefit more than any one individual farmer. Some suggest that the state can and will play a central role in late-developing societies—the challenge is only to build a strong bureaucracy free of corruption and committed to serving national as opposed to narrow personal, local, and class interests. Statistically, it has been shown that societies with strong administrative structures in the countryside have tended to have more rapid agricultural growth over the last couple of decades.5

Yet other authors continue to identify interventionist governments as a major source of economic distortions in rural development. To these authors, it is vain to speak of making a bureaucracy serve national interests when the urban middle classes have many more political resources than peasants. In this situation, active state intervention in the market makes it likely that urban interests in things such as industrial investment and cheap grain will be served while cultivator interests in things such as agricultural research and adequate grain prices will be ignored. Even when not serving particular class interests, bureaucracies cause problems of their own, being slower than the market to respond to new situations and serving as much to protect individual bureaucratic careers as larger social purposes. These problems are perceived as particularly acute in socialist regimes, and Soviet collective farms are often taken as an ideal-typical example of how agriculture can be stifled by the drive to fund industrialization by draining agriculture and by other sorts of improper bureaucratic interventions.6

It seemed for a time that China had avoided many of the latter types of problems. Based on a peasant revolution and with much talk about serving the peasants, it appeared that collective agriculture was not being used to drain resources from the countryside into cities or urban industry. And, except in the Great Leap Forward period, the state appeared to avoid heavy-handed bureaucratic management of agriculture in favor of more village autonomy, which allowed small peasant communities to make their own decisions about which crops and cultivation methods suited their area. Thus, China seemed to enjoy the benefits of many bureaucratic services from a strong central state without many of the disadvantages.

In hindsight, it appears that the peasant base of the Chinese revolution made less difference in the management of agriculture than we once thought. As Lardy explains in this volume, many aspects of the Soviet model were replicated in China in the three decades following the revolution. Even while the tax burden was lighter and the differential in prices between urban and rural goods was not so severe as in the early years of collective agriculture in the Soviet Union, prices were still slanted sufficiently in favor of the urban sector that there was a net drain out of agriculture. The state invested little in agriculture in return, even while increasingly large subsidies were being given to underwrite the food, hou...