eBook - ePub

Third Generation Leadership and the Locus of Control

Knowledge, Change and Neuroscience

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Third Generation Leadership and the Locus of Control

Knowledge, Change and Neuroscience

About this book

There have been two critical leadership approaches. First Generation Leadership (command and control) was the dominant model until the 1940s. Second Generation Leadership (compliance coupled with rewards and punishments) is still dominant today. This approach is being rejected by 'Generation Y ', threatening the longevity of traditional organisations. In Third Generation Leadership and the Locus of Control, Douglas Long acknowledges the need for a leadership approach that elicits engagement, commitment, and enhanced personal, group, and organisational accountability. This is Third Generation Leadership. At its core lies the issue of where we centre our brain's locus of control and how this impacts on our understanding of and approach to leadership. With examples from everyday situations, underpinned by research, this book is about understanding and applying aspects of neuroscience critical for tomorrow's world. It provides a framework for addressing problems through insights into how the way we use our brains affects values, worldviews and behaviours. The author introduces the concept of 'red zone - blue zone' to explain the differences between a brain controlled by its stem-limbic areas (red zone) and the limbic-cortical cortex areas (blue zone). This becomes a short hand for describing and applying knowledge from neuroscience to encourage practitioners in leadership and management roles to achieve desired outcomes through becoming acquainted with different areas of their brain. Anyone grappling with what is required to deal with Generation Y people in a networked and mobile age will welcome this introduction to the world of third generation leadership.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Third Generation Leadership and the Locus of Control by Douglas G. Long in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Understand the Past

In which we consider the leadership approaches that dominate today

1

The Background to Third Generation Leadership

Once upon a time, way back in the days when the earth was thought to be flat and dinosaurs roamed, back in the times before my father was a little boy, there were two types of people: first there were the rich and the powerful; and then there was everyone else.

In this world, the rich and powerful owned property and businesses. They provided jobs and produced the goods and services that everyone needed. Many of these people had taken risks in setting up their businesses – they had invested their money to create a business and they wanted to make a lot more money as a result. To do this they employed only the minimum number of people and they kept the wages low. Very often they made their employees work long hours in poor conditions. They rented out their properties at the highest possible figure and they sold their goods and services at the highest possible price. The result was that the rich became even more rich and, well, after all, what did the rest matter? Naturally, everyone wanted to be rich! But, as the old song puts it:1

There’s nothing surer; the rich get rich and the poor get poorer.

Of course, those people who weren’t rich didn’t like this situation at all. But nobody listened to them. The rich made the rules and, no matter what might be said, in reality the rules were designed to help them become even more rich and powerful.

In around 1899 Henry Ralph Harvey Chalmers joined the Bank of New Zealand (BNZ) as a junior clerk.2 In 1957 he finished his association with BNZ as chairman. Over the intervening 58 years he had moved steadily through the ranks until becoming general manager, and then, after retirement, first a director and ultimately chairman. The only time he was not employed by BNZ was during the First World War when, as a soldier, he fought on the Somme. Harry, as he was known, was certainly intelligent but he received no formal academic, skills or management training over his entire working life. His was a fairly typical success story for the first half of the twentieth century: join a big organisation, work hard, do as you are told, ensure you don’t seriously blot your copy book, and take every promotion offered no matter what the inconvenience. Harry, my paternal grandmother’s brother, died in 1971 and I was present at the funeral where he was rightly hailed as one who had made a significant contribution to both banking and to society at large in New Zealand.

My Uncle Harry was a typical 1G Leader (First Generation Leadership is based on compliance – see Chapter 3) – a manager in a First Generation Leadership organisation – who operated very effectively both at work and in the family primarily in a somewhat paternal, command and control format.

My secondary schooling was at Auckland Grammar School, a boys-only state school in New Zealand. Auckland Grammar, like most other schools of the era in those long-gone days, had a proud history of caning miscreants. (I must stress that Auckland Grammar changed this approach many years ago.) In my day, one Master started his first class with new students by giving a lecture on the physics relating to the most effective way of caning (i.e. causing the most pain) complete with stick diagrams drawn on the board to illustrate his points. Another Master would chalk a ‘magic circle’ at the top of a flight of stairs and, after you had stepped into the circle and bent over, he would cane you – the contest was to ensure you didn’t fall face-first down the stairs on impact. Yet another Master once stated he would cane (three strokes each) every boy in our class of 35 if anyone again interrupted his lecture. We made sure he had to cane us all during that class and I understand he never again made a similar threat!

In around 1958 Terry McLisky joined Auckland Grammar School as a maths and physics teacher. I was fortunate to have him as my teacher in both subjects for two years. Terry was different. I remember in his first class with us he suggested that if we wanted to learn we should sit at the front: if not, sit at the back and ‘do what you like but don’t interrupt the class’. I can recall only a few instances when any student sat at the back and I have no recollection of Terry ever resorting to the cane or even detentions in order to maintain attention.

Terry McLisky was a typical 2G Leader (Second Generation Leadership is based on conformance – see Chapter 4) – one of several at Auckland Grammar and other schools who were somewhat ahead of their time – who saw that encouraging conformance through the provision of positive reinforcement, such as personalised teaching and showing students that he really wanted to help them, would get far better results than enforcing obedience.

Today the world has moved beyond both Harry Chalmers and Terry McLisky. Since the 1980s the rapid development of computer technology, the Internet and social networking has revolutionised our access to knowledge as well as the way in which we interact. Those of us who completed our schooling in the 1950s and 1960s may have some difficulty in this new world, but those who have been schooled since the 1980s can hardly even imagine anything else. To understand this shift we need to understand the underpinnings of leadership.

Over the years emphasis has been placed on leadership traits, leadership attitudes and leadership behaviours. Much research has been done into each of these and myriad books have been written explaining why one or the other (or what combination of the three) is necessary for effective leadership.3 For some 50 years there have been leadership training programmes of varying degrees of effectiveness and quality and there are champions and success stories for every approach that has been developed. We needed the work done by this research and these programmes.

Traditional approaches to leadership have not paid much attention to the world of neuroscience – mainly because the research that enables us to have these new understandings was not possible until relatively recently. Accordingly, as I say, we have been given models of leadership that are based on physical or character traits, attitudes and/or behaviours. We have been told that the activities of a leader are contingent on the situation in which the leader finds him or herself; we have learned that we can develop new attitudes; and we have been told to develop appropriate habits in order to provide effective leadership. Almost all of the approaches that have been developed are underpinned by serious, peer-reviewed research and they stand up to scrutiny. They have been used effectively by individuals and organisations across the globe with, understandably, differing cultures finding some leadership approaches more appropriate than others. They have made a powerful contribution to the way in which we lead people today, whether in government, the military, business, school, society at large, or in the home.

But now they have either reached, or are very close to reaching, their ‘use by date’. Unfortunately it seems that much of the currently available leadership material fails to realise this. This lack of awareness relating to ‘use by date’ is then reflected in the leadership education and training provided in many institutions and organisations.

When, from 1988 to 2001, I was conducting the programme Leadership in Senior Management at Macquarie Graduate School of Management in Sydney, a regular comment from participants was that the programme was different from what they expected. Consistently (but fortunately only from a minority of participants) came the comment that they expected to concentrate on how the leader interacted with his or her followers. These participants were seeking information on how to deal with the different situations in which leadership was exercised or assistance on how to deal with the interpersonal relationships of leadership interactions. Instead, what the 90 or so participants each year got was a programme that looked at leadership from a macro perspective – leadership as it impacted on total organisational performance through drawing together the variables that ultimately determine success or failure – and dealing with different situations and/or with interpersonal relationships is only a small part of this. Leadership in Senior Management was significantly different from most other leadership programmes being offered in Australia and was not popular with some of my academic friends because it was based on a different research base and promoted a different leadership perspective from that with which they were most comfortable.

Back in the early 1950s I remember being introduced to Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess.4 In that show there is a song, ‘It Ain’t Necessarily So’, which points out that even if something is written in the Bible it may not be entirely accurate.

My parents strongly disapproved of this song and, therefore, of Porgy and Bess. They were devout evangelical Baptists and the thought of questioning what the Bible said was totally unacceptable – they were appalled when one day I came home from a friend’s house and I was singing the lyrics. Perhaps that was why, as a developing youth, I continued to sing them when I was frustrated about getting my own way! Perhaps, too, it was one of the reasons why, many years later, among other things, I studied theology!

But these words used to come back to me whenever people questioned why I taught a different approach to leadership from that which was in the majority of texts, articles and popular books. I needed to point out that just because traditionally the ‘authorities’ have told us that ‘leadership’ is this or that, doesn’t necessarily mean they are right. Close examination of the fine print and a careful observation of reality just might alert us to the fact that ‘it ain’t necessarily so’!

Today the developing study of modern neuroscience has enabled us to look at a whole raft of things a little differently. Included on this raft is the matter of leadership.

One key issue that has arisen from the field of neuroscience relates to the brain’s locus of control. The role of this book is neither to give a comprehensive overview of modern neuroscience nor to argue the pros and cons of the various theories that have emerged. Rather, this book utilises learning from only a very small aspect of modern neuroscience. In this book I utilise a basic understanding of the areas of the brain that control our attitudes and behaviours as these relate to the leadership function.

Jonah Lehrer5 is one of the writers on neuroscience who has provided a simple way of understanding how the brain has developed and the manner in which our emotions impact on every part. Between 2002 and 2006 I was involved with research in state and Catholic schools in Victoria, Australia and in England. (The research was lead by John Corrigan.) Data was obtained from some 50 schools (almost all secondary) and involved approximately 80 teachers per school, four parents per teacher and 240 students per school. This data presented us with some difficult questions and finally led us to understand that the key to effective leadership was to be found in concepts from modern neuroscience and, in particular, in relation to our brains’ locus of control. Lehrer’s work was very helpful in this understanding. In The Success Zone6 we combined our education research with concepts such as those developed by Lehrer as a way of explaining what we called the ‘red zone’–‘blue zone’ concepts. Building on the underpinning of neuroscience we developed a shorthand approach for describing the brain’s possible loci of control.

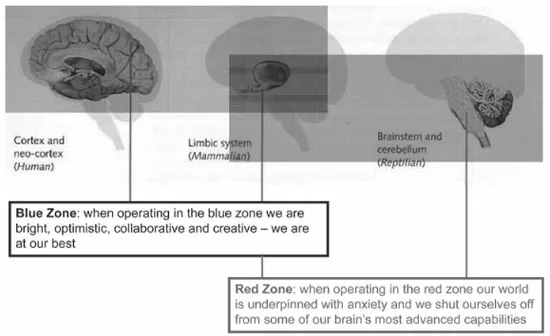

Figure 1.1 Blue Zone–Red Zone

Neuroscience has found that one’s locus of brain control is complex but basically centred in the combination of several brain areas. Mowat et al. called the reptilian-limbic combination The Red Zone and the neocortical-limbic combination The Blue Zone. In The Success Zone these are referred to as ‘two minds’. These terms, ‘red zone’ and ‘blue zone’, will be used extensively in this book and are used with permission. The concept of ‘red zone’ and ‘blue zone’ is explained in some depth in Chapter 6, however, in brief they refer to our brain’s areas (or ‘loci’) of control (see Figure 1.1).

When using these terms to describe the brain’s loci of control it is important to note that they are simply a shorthand expression relating to a field of study that is very complex and still developing. There is much more to modern neuroscience than is implied in this simple model but, from the perspective of understanding leadership development from First Generation Leadership to Third Generation Leadership, these are the key areas of interest because they refer to the brain’s possible areas for the control of our attitudes and behaviours.

When the brain’s area of control is centred in the red zone, the emphasis is on survival. This is the part of the brain that leads to perception of threat (real or imagined) and so to the ‘fight, flight, or freeze’ syndrome that we see particularly in reptiles and lower level animals. There is no conscious thought in this. Life just ‘is’ or ‘isn’t’ – it is not something of which the animal is consciously aware – and instinct makes us want to hold on to life if possible so we respond to threat in a way that offers the chance of living another day.

When this perceived threat is physical (for example we are threatened with violence or are in danger of being run over by a bus) then the dominance of the red zone is essential. Instinctive action is required and occurs. Unfortunately, however, because the red zone is dominated by the reptilian brain it is not capable of distinguishing between real threats or imagined threats and so it reacts in the same way whether or not a threat actually exists. In the modern world, a red zone locus of control can lead to some very inappropriate responses when a person perceives a threat even when there is no such intent from other parties and we see this all too frequently in some domestic, social, business, national and international events. Red zone locus of control also leads to the commonly encountered issue of resistance to change.

When the brain’s area of control is in the blue zone we have the opportunity to see things differently. Because the blue zone is dominated by the cortical brain – that part of the brain which deals with thought, voluntary movement, language and reasoning (in other words ‘with higher level learning’) – we have the ability to see things as they actually are and to distinguish between real and imagined threats. This enables us to make a more appropriate response and to find ways of dealing with ‘the new’ in exciting and innovative ways. When operating with a blue zone locus of control we are better able to deal with complexity and ambiguity than is the case when we operate out of a red zone locus of control.

It must be noted, however, that this ‘red zone–blue zone’ dichotomy has nothing to do with our emotions. The areas of the brain that brings about emotion are common to both the blue zone and the red zone. In other words, it is not a case of ‘red zone = unhappy’, ‘blue zone = happy’, or anything like that. People with their brain’s locus of control in the blue zone will have exactly the same range of emotions as they have always had. Any difference will relate to the way in which these emotions are handled.

What modern neuroscience has done is to enable us to add another layer to the leadership process. By understanding how the brain’s area of control impacts on our everyday behaviour and by learning how to manage down the red zone while simultaneously managing up the blue zone we are able to take a new look at the whole concept of leadership and to discover totally new ways of dealing with the issues that we are facing today as well as those that will emerge in coming years.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, we have encountered a situation in which the working hours of Western industrialised countries seem to be increasing. There seems to be an assumption that employees, particularly in ‘white collar’ jobs, should be prepared to work whatever hours are required to meet targets set by their bosses. Very often it seems that those in management and executive positions are expected to be available 168 hours a week (or ‘24/7’) and to have no interests or involvements other than their work. In many ways we seem to have regressed to the situation that pertained over 100 years ago.

From reading newspapers as well as from talking with people, the impression is gained that many people today are scared of taking leave that is due or even of seeking medical and/or dental treatment that might be required because time away from the workplace could be penalised in the next round of layoffs or cost-cutting. We encounter situations in which companies crash, with employees, minor creditors and small stockholders left out of pocket – sometimes while directors, executives,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- About the Author

- Prologue

- Introduction

- PART ONE UNDERSTAND THE PAST

- PART TWO LIVE IN THE PRESENT

- PART THREE CREATE THE FUTURE

- Epilogue

- Appendices

- Index