eBook - ePub

Numismatic Archaeology of North America

A Field Guide

Marjorie H. Akin, James C. Bard, Kevin Akin

This is a test

Share book

- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Numismatic Archaeology of North America

A Field Guide

Marjorie H. Akin, James C. Bard, Kevin Akin

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Numismatic Archaeology of North America is the first book to provide an archaeological overview of the coins and tokens found in a wide range of North American archaeological sites. It begins with a comprehensive and well-illustrated review of the various coins and tokens that circulated in North America with descriptions of the uses for, and human behavior associated with, each type. The book contains practical sections on standardized nomenclature, photographing, cleaning, and curating coins, and discusses the impacts of looting and of working with collectors. This is an important tool for archaeologists working with coins. For numismatists and collectors, it explains the importance of archaeological context for complete analysis.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Numismatic Archaeology of North America an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Numismatic Archaeology of North America by Marjorie H. Akin, James C. Bard, Kevin Akin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Archéologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

What is Numismatics?

Introduction to Numismatics

Numismatics is the study of coins and related circulating currency. Exonumismatics, a subfield of numismatics, is the study of coin-like items, such as tokens and medals. The shell and stone beads that were once used as money by some Native Americans are also part of the broad field of numismatics and are given some attention here but are not the focus of the book. This book focuses on the coins, tokens, and medals that could be encountered in the course of archaeological excavations in North America.

This book is primarily intended to help archaeologists and historians, as well as people working in the fields of material culture and museum studies, understand just how much information can be gleaned from the complex objects that are collectively referred to as numismatic artifacts. Because they are so complex, combining the economic, political, and aesthetic values of their temporal context, it is not surprising that any archaeologist working with such recovered items would need numismatic resources to help understand their significance. New archaeological methods of analysis and what they can reveal will be of interest to more experienced numismatists who want to deepen their understanding and appreciation of numismatic materials and who wish to learn about the relationship between numismatics and archaeology.

Essential Vocabulary

The definitions of some basic terms listed here have changed over the past two centuries, as have the additional terms that can be found in the glossary. There are also differing definitions and methods of classification used for coins and other circulating currency in the Old World and in the New World. The short review of the history of numismatics presented here will help the reader understand how these differences came about and how that has influenced archaeological analysis in different places. We begin here with some essential definitions as they are used throughout the book.

Numismatics is the formal study of coins, tokens, and other similar artifacts; it includes their production and circulation and their uses and reuses. It also includes, but is not limited to, the investigation of the functions of these items as economic tools in the form of money. Coin and medal collecting is a common feature of numismatics. Although few coin collectors are numismatists, almost all numismatists are coin collectors.

North American numismatic investigations include a high proportion of material that was not issued by a government. This is because the colonial powers usually neglected to provide sufficient small change for the economies of their colonies and because “frontier” and developing areas often had severe shortages of official currency, forcing people to depend on local circulating media (usually tokens) that were not recognized by governmental authorities. For that reason the term numismatics as used in this book includes the subfield of exonumismatics, the study of tokens, medals, and similar material not recognized by any government or central authority.

Numismatics also includes the study of the appearance and morphology of the coins and medals as items of aesthetic value. There are differences in emphasis on particular aspects of numismatics in various parts of the world. In Europe, for example, there is a long tradition of studying the art of numismatics, with a focus on design, the artistic rendering, and iconography. In the United States the emphasis is more often on the function and distribution of the coins and what that reveals about history and how people behaved in relation to the material; although it would be inaccurate to say that aesthetic values are not also appreciated.

Numismatic archaeology is a subfield of archaeology that focuses on the study of coins and related objects, especially those found in formal archaeological investigations, to aid in the interpretations of archaeologically derived information. It uses archaeological methods and theories and applies principles of analysis used on other artifact classes to expand our understanding of the past. Although examining the materials that are recovered is the way we add to existing knowledge of the production, circulation, and other uses and reuses of numismatic material, it is the human activity, and the culture that drives it, that is the ultimate subject of numismatic archaeology.

Figure 1.1. Ethan White holds a Spanish maravedi recovered in Florida. He is correctly grasping the coin by the edges. Photo credit Dr. Ashley White.

In Europe and China where coins have been used for more than two thousand years longer than in the New World, numismatics is an established and widespread tool for archaeological investigations. In the New World, especially North America, numismatic studies are applicable only to the recent historical past, a period not exceeding four hundred years in most areas. As a result, numismatic archaeology is not as well known or well used as a tool for the reconstruction of past human behavior in North America as it is in other parts of the world.

Money is any item that is customarily used as a medium of exchange of wealth and a measure of value within a society. Before the development of coins, which occurred about 2,600 years ago in Asia Minor, and simultaneously and independently in China, various bartered commodities fulfilled money’s function. In the past, items such as shells, ingots, and pelts served some of the functions of money. In addition, there were a number of innovative methods of dealing with economic exchanges, such as the potlatch that was a form of wealth redistribution used by Pacific Northwest native peoples. Today we use paper currency, paper and electronic checks, and electronically coded plastic cards issued by banks and individual businesses to supplement coins and paper notes as money.

Perhaps the most useful description of what money is, from an anthropological perspective, can be found in Monies in Societies (Neale 1976). According to Neale, money has a number of defining functions and traits. Money functions as: 1) a medium of exchange; 2) a store of value; 3) a unit of account; and 4) a means of payment. There are many ways to obtain money, but generally we work for it so that we can get things that we cannot produce using only our own labor. We go to stores and engage in exchanges, we maintain bank accounts, we accrue and calculate wealth and debts, and we pay debts, all with various forms of money. We recognize that money has regular characteristics that allow us to differentiate what will serve as money (the means to accomplish the activities above), and what will not be accepted as money.

Additional traits of money are that it is durable, portable, quantifiable in a system of small gradations (like a system of weights and measures), and fungible ([any unit or units of a money are substitutable for any other units of equal value in the same system] Neale 1976:8).

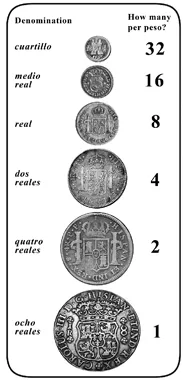

Figure 1.2. Fungible means that different coins may be substituted for each other within a monetary system, in the right quantities. Thirty-two quartilllos were worth the same as eight reales throughout Spanish America.

The way to decide whether or not any given form of money will pass (serve its anticipated function) is to determine if it has the defining characteristics of circulating money. The most important defining characteristic for this purpose is not, as might be expected, simply the physical appearance of the money (anything identified as a forgery will not pass even if it looks similar to the original). It is because a social or political authority guarantees the utility of the money for exchange and that the user recognizes the authority of the body that issues the money that makes it valid. In the case of coins, the authority may be shown in an inscription of a government or issuing authority, like a ruling sovereign. In the United States, we use coins and bills issued by the United States Mint and the Federal Reserve because we recognize the federal government as the political and economic authority. We may also use money orders and checks as forms of money because we recognize that the government has given the bank the authority to exchange them for money issued by the government. When checks are refused, it is because there is a question about legitimacy of the authorization to exchange them for money.

The authority that grants legitimacy to money is not always a political entity. Some money, particularly money based on its intrinsic value (bullion value), gains its legitimacy through common consent of the users. During the American colonial period, when there was often a question of which government, if any, was in control in any given area, people relied on the intrinsic value of the metal to define the value of any particular piece of money. In China, during different historic eras, the imperial control wavered, and in some regions imperial control was practically nonexistent. Under these circumstances the intrinsic value of the copper in the coins gave them their value. Because coin sizes varied over the years, and even genuine coins often had less copper or more zinc than the standards specified, the community where the coins circulated came to a consensus about the value of different coins depending on the coins’ actual composition instead of what the composition was supposed to be.

When a piece of money has intrinsic value due to precious metal content, it may circulate more widely geographically or temporally, that is in areas outside the territory of the issuing authority or after that authority ceases to exist. Circulating currency refers to money that is recognized as a medium for conducting economic exchanges within a society. However, in colonial and frontier areas, especially where geographical boundaries and political authority were uncertain, what passed for money is not always so easy to understand. Because it is imperative that archaeological artifacts be interpreted within their appropriate cultural context, one of the goals of this book is to help readers understand why certain coins and tokens are found in particular locations and circumstances. Also, because the reuse of various coins and tokens was a common occurrence in North America, we need to determine what happened to the coins and tokens just before they entered the archaeological record instead of making assumptions based on how those materials circulated in other parts of the world.

Coins are a specific form of money. Coins normally consist of a metal disk of a size relatively easy to transport on one’s person, that has various inscriptions related to its value, and that has its origin stamped or cast on both sides, although there are some exceptions. The earliest coins were composed of metals, such as silver, gold, electrum, and copper, which gave them an intrinsic value, a value based on the market value of the metal itself. As economies and political states became more complex, coins came to represent a value that was based to a greater or lesser degree on the authority of the government that produced them rather than strictly on the amount of precious metal they contained. Such coins, however, normally were only worth their metal value in areas outside the borders of the issuing state.

Coins are initially created to be a form of money, but that initial function can change over time as surrounding circumstances change. Sometimes a government issuing coins and other forms of money, such as paper notes, can break down causing the recognition of the money to fail. Such was the case with Confederate banknotes at the end of the American Civil War. They became noncurrency souvenirs and keepsakes that had no monetary value but a high symbolic content, both as reminders of the “lost cause” to the supporters of the slave owners and to Union supporters as trophies of victory over the slave power. Their historic or symbolic value can cause people to pay a fluctuating market price for such items as collectibles, but they are not recognized as money in that situation.

In other situations, coins are moved out of the geographic or political region where they function as money, and people find other things to do with them. It was a common practice in many parts of the world to use coins as a decoration on clothing; some coins have medical uses; and some are used as game pieces. There are actually many nonmonetary uses for coins, and if coins end up in an archaeologist’s screen after their function has been changed, they can o...