eBook - ePub

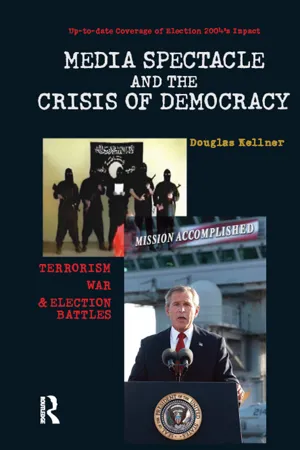

Media Spectacle and the Crisis of Democracy

Terrorism, War, and Election Battles

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Douglas Kellner's Media Spectacle and the Crisis of Democracy: 9/11, the War on Iraq, and Election 2004 investigates the role of the media in the momentous political events of the past four years. Beginning with the role of the media in contested election of 2000, Kellner examines how corporate media ownership and concentration, linked with a rightward shift of establishment media, have disadvantaged the Democrats and benefited George W. Bush and the Republicans. Exploring the role of media spectacle in the 9/11 attacks and subsequent Terror War in Afghanistan and Iraq, Kellner documents the centrality of media politics in advancing foreign policy agendas and militarism. Building on his analysis in Media Spectacle (Routledge 2003), Kellner demonstrates in detail how conflicting political forces ranging from Al Qaeda to the Bush administration construct media spectacles to advance their politics. Two chapters critically engage the role of the media in the buildup to the Iraq war and the media-centric nature of Bush's Iraq invasion and occupation. Final chapters delineate the role of the media in the highly contested and significant 2004 election campaign that many believe to be one of the key political struggles of the contemporary era. Criticizing Bush's unilateralism, Kellner argues for a multilateral and cosmopolitan globalization and the need for democratic media to help overcome the current crisis of democracy in the United States.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Media Spectacle and the Crisis of Democracy by Douglas Kellner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Grand Theft 2000: Media Spectacle and a Stolen Election

When the real world changes into simple images, simple images become real beings and effective motivations of a hypnotic behavior. The spectacle has a tendency to make one see the world by means of various specialized mediations (it can no longer be grasped directly).1

—Guy Debord

THE 2000 U.S. PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION, one of the closest and most hotly contested ever, was from start to finish a media spectacle.2 Despite predictions that the Internet was on its way to replacing television as the center of the information system, television in the 2000 U.S. election was perhaps more influential than ever. The proliferation of channels on cable and satellite systems multiplied political discourse and images, with several presenting round-the-clock political news and discussion. These cable news programs were organized as forms of media spectacle, with highly partisan representatives of both sides engaging opponents in dramatic competition. The fight for ratings intensified the entertainment factor in politics, fueling the need to generate compelling political spectacle to attract audiences.

The result was unending television discussion programs with commentators lined up for the Republicans or Democrats, as hosts pretended to be neutral, but often sided with one candidate or another. Of the 24-hour cable news channels, it was clear that the Rupert Murdoch–owned Fox network was unabashedly pro-Republican, and it appeared that the NBC-owned cable networks MSNBC and CNBC were also partial toward Bush.3 CNN and the three major networks claimed to maintain neutrality, although major empirical studies of television and press coverage of the election indicated that the media on the whole tended to favor Bush (see below).

By all initial accounts, it would be a close election, and both sides furiously tried to spin the media, getting their “message of the day” and a positive image of their candidate on screen or into the press. Both sides provided the usual press releases and sent out e-mail messages to the major media and their supporters, which their opponents would then attempt to counter. The competing campaigns also constructed elaborate websites that contained their latest “messages,” video clips of the candidates, and other information on the campaigns.4 Both sides staged frequent photo opportunities, saturated the airwaves with ads, and attempted to sell their candidate to the voters. In an era of spectacle politics, presidential candidates were a brand name to be sold to voters and campaigns were dominated by marketing and public relations techniques.

Media Spectacle in Election 2000

We mortals hear only the news and know nothing at all.

—Homer

Throughout the summer, there was not much intense focus on the campaigns among the public at large until the political conventions took place, where both parties traditionally produce spectacles to provide positive images of their candidate and party. The Republicans met first, in Philadelphia from July 31 to August 3, filling their stage with a multicultural display of supporters, leading pundits to remark that more people of color appeared on stage than were in the audience of the lily-white conservative party that had not been friendly to minorities. The Democrats met in Los Angeles in mid-August and created carefully planned media events to show off their stars, the Clintons and the Gores, with Al and Tipper’s long kiss the most circulated image of the event. For the first time, however, major television networks declared that the political party conventions were not important news stories, but were merely partisan events, and they severely cut back on prime-time coverage allotted the spectacles. In particular, NBC and the Fox network broadcast baseball and entertainment shows rather than convention speeches during the early days of both conventions. CBS’s Dan Rather dismissed the conventions as “four-day infomercials” (CBS News, August 15).

Nonetheless, millions of people watched the conventions, and both presidential candidates got their biggest polling boosts after their respective events, thus suggesting that the carefully contrived media displays were able to capture an audience and perhaps shape viewer perceptions of the candidates. After the conventions, no major stories emerged and not much media attention was given to the campaigns during the rest of August and September in the period leading up to the presidential debates. The Gore campaign seemed to be steadily rising in the polls as the Bush candidacy appeared to be floundering.5

The relatively inexperienced Republican candidate was caught on open mike referring to a New York Times reporter as a “major-league asshole,” with Bush’s vice presidential choice, Dick Cheney, chiming in “big time.” Although the Bush team publicly proclaimed that it would not indulge in negative campaigning, a television ad appeared attacking Gore and the Democrats that highlighted the word “RATS.” Critics accused the Bush campaign of attempting to associate the vermin with DemocRATS/bureaucRATS. Bush denied that his campaign had produced this “subliminable” message (in his creative mispronunciation) at the same time that an ad producer working for him was bragging about it.

As the camps haggled about debate sites and dates, it appeared that Bush was petulantly refusing the forums suggested by the neutral debate committee and was perhaps afraid to get into the ring with the formidable Gore. Since the 1960s the presidential debates have become popular media spectacles that are often deemed crucial to the election. Hence, as the debates began in October, genuine suspense arose and significant sectors of the populace tuned in to the three events between the presidential candidates and the single debate between the competing vice presidential candidates. On the whole, the debates were dull, in part because host Jim Lehrer asked unimaginative questions that simply allowed the candidates to feed back their standard positions on Social Security, education, Medicare, and other issues about which they had already spoken day after day. Neither Lehrer nor others involved in the debates probed the candidates’ positions or asked challenging questions on a wide range of issues from globalization and the digital divide to poverty and corporate crime that had not been addressed in the campaign. Frank Rich described the first debate in the New York Times as a “flop show,” and Dan Rather on CBS called it “pedantic, dull, unimaginative, lackluster, humdrum, you pick the word.”6

In Election 2000, commentators on the debates tended to grade the candidates more on their performance and style than on substance, and many believe that this strongly aided Bush. In the postmodern image politics of the 2000 election, style became substance as both candidates endeavored to appear likable, friendly, and attractive to voters. In the presidential debates when the candidates appeared mano a mano to the public for the first time, not only did the media commentators focus on the form and appearance of the candidates rather than the specific positions they took, but the networks frequently cut to “focus groups” of “undecided” voters who presented their stylistic evaluations. After the first debate, for instance, commentators noted that Gore looked “stiff” or “arrogant” and Bush appeared “likable.” After the second debate, Gore was criticized by commentators as too “passive,” and then after the third debate too “aggressive,” whereas Bush, as we’ll see below, was not strongly criticized for style or substance.7

Bush’s appeal was predicated on his being “just folks,” a “good guy,” like “you and me.” Thus, his anti-intellectualism and lack of gravity, exhibited every time he opened his mouth and mangled the English language, helped promote voter identification. As sometime Republican speechwriter Doug Gamble once mused, “Bush’s shallow intellect perfectly reflects an increasingly dumbed-down America. To many Americans Bush is ‘just like us,’ a Fox-TV President for a Fox-TV society.”8

It was, however, the spectacle of the three presidential debates and the media framing of these events that arguably provided the crucial edge for Bush. At the conclusion of the first Bush-Gore debate, the initial viewer polls conducted by CBS and ABC declared Gore the winner. But the television pundits seemed to score a victory for Bush. Bob Schieffer of CBS declared, “Clearly tonight, if anyone gained from this debate, it was George Bush. He seemed to have as much of a grasp of the issues” as Gore. His colleague Gloria Borger agreed, “I think Bush did gain.” CNN’s Candy Crowley concluded, “They held their own, they both did…. In the end, that has to favor Bush, at least with those who felt … he’s not ready for prime time.”9

Even more helpful to Bush was the focus on Gore’s debate performance. Gore was criticized for his sighs and style (a “bully,” declared ABC’s Sam Donaldson) and was excoriated for alleged misstatements. The Republicans immediately claimed that Gore had “lied” when he told a story of a young Florida girl forced to stand in class because of a shortage of desks. The school principal of the locale in question denied this, and the media had a field day, with a Murdoch-owned New York Post boldface headline trumpeting “Liar! Liar!” Subsequent interviews indicated that the girl did have to stand and that there was a desk shortage, and testimony from her father and a picture confirmed this, but the damage to Gore was already done. Moreover, Gore had misspoken during the first debate in a story illustrating his work in making the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) more efficient, claiming that he had visited Texas with its director after a recent hurricane. As it turns out, although Gore had played a major role in improving FEMA and had frequently traveled with its director to crisis sites, and although he had been to Texas after the hurricane, the fact that he had not accompanied the director in the case cited accelerated claims that Gore was a “serial exaggerator” or even a liar who could not be trusted.

Republican pundits obsessively pursued the theme that Gore was a liar. In the Wall Street Journal (October 11, 2000), ideologue William Bennett wrote: “Albert Arnold Gore Jr. is a habitual liar. … The vice president lies reflexively, promiscuously, even pathologically.” In fact, the alleged lies were largely Republican propaganda. This Republican mantra was repeated throughout the rest of the campaign, and although the press piled on Gore every time he made a minor misstatement, Bush was able to get away with whoppers in the debate and on the campaign trail on substantial issues.10 For example, whereas he claimed in a debate with Gore that he was for a “patients’ bill of rights” that would allow patients to sue their HMOs for malpractice, in fact, Bush had blocked such policies in Texas and opposed a bill in Congress that would allow patients the right to sue. Few critics skewered Bush over the misstatement in the second debate, delivered with a highly inappropriate smirk, that the three racists who had brutally killed a black man in Texas were going to be executed. In fact, one had testified against the others and had been given a life sentence in exchange; moreover, because all three cases were on appeal it was simply wrong for the governor to claim that the men were going to be executed, since this undercut their right of appeal. The media also had given Bush a pass on the record number of executions performed under his reign in Texas, the lax review procedures, and the large number of contested executions where there were questions of mental competence, proper legal procedures, and even evidence that raised doubts about Bush’s execution of specific prisoners.

Although a fierce argument over prescription drugs in the first debate led to allegations by Gore that Bush was misrepresenting his own drug plan, driving Bush to assault Gore verbally, the media did not bother to look and see that Bush had misrepresented his plan and that Gore was correct, despite Bush’s impassioned denials, that seniors earning more than $25,000 a year would get no help from Bush’s plan for four or five years. Moreover, after the third and arguably decisive presidential debate, commentators and pundits were heavily pro-Bush. On MSNBC, for example, in questioning Republican vice presidential candidate Dick Cheney about the third debate, Chris Matthews lobbed an easy question to him attacking Al Gore; moments later when Democratic House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt came on, once again Matthews assailed Gore in his question! Pollster Frank Luntz presented a focus group of “undecided” voters, the majority of which had switched to Bush during the debate and who uttered primarily anti-Gore sentiments when interviewed (MSNBC forgot to mention that Luntz is a Republican pollster). Former Republican Senator Alan Simpson was allowed to throw barbs at Gore, to the assent of host Brian Williams, and no Democrat was allowed to counter the Republican in this segment. The pundits, including Matthews, former Reagan-Bush speechwriter and professional Republican ideologue Peggy Noonan, and accused plagiarist Mike Barnacle, all uttered pro-Bush messages, while the two more liberal pundits provided more balanced analysis of the pros and cons of both sides in the debate, rather than just spin it for Bush.

Gore was on the defensive for several weeks after the debates, and Bush’s polls steadily rose. Moreover, the tremendous amount of coverage of the polls no doubt helped Bush. Although Gore had been rising in the polls from his convention up until the debates, occasionally experiencing a healthy lead, the polls were favorable to Bush from the conclusion of the first debate until the election. Almost every night, the television news opened with the polls, which usually showed Bush ahead, sometimes by 10 points or more. As the election night results would show, these polls were off the mark, but they became the story of the election as the November 7 vote approached. The majority of the mainstream media polls on the eve of the election put Bush in the lead (although the Zogby/Reuters and CBS News polls put Gore slightly ahead in the popular vote). Media critic David Corn noted that commentators such as John McLaughlin, Mary Matalin, Peggy Noonan, and many of the Sunday network talk-show hosts prophesied a sizable Bush victory and tended to favor the Texas governor.11 Joan Didion reports, by contrast, that seven major academic pollsters presenting their data at the September 2000 American Political Science Association convention all predicted a big Gore victory, ranging from 60.3 percent to 52 percent of the vote.12

Academic pollsters tend to use rational-choice models and base their results on economic indicators and in-depth interviews; they seem, however, to downplay moral values, issues of character, the role of media spectacle, and the fluctuating events of the election campaigns. Indeed, academic pollsters argue that the electorate is basically fixed one or two months before the election. Arguably, however, U.S. politics is more volatile and unpredictable and swayed by the contingencies of media spectacle, as Election 2000 and its aftermath vividly demonstrated. Robert G. Kaiser, in “Experts Offer Mea Culpas for Predicting Gore Win” (Washington Post, February 9, 2001), presents interviews with major political scientists who had predicted a strong win for Gore based on their mathematical models and data collected months before election day. One professor admitted that the “election outcome left a bit of egg on the faces of the academic forecasters,” whereas others blamed a poor Gore campaign, “Clinton fatigue,” and an unexpectedly strong showing by Ralph Nader. One defiant forecaster said that the election was simply weird, “on the fringe of our known world, a stochastic [random] shock.”

The polls were one of the scandals of what would turn out to be shameful media coverage of the campaign. Arianna Huffington mentions in a November 2, 2000, syndicated column that on a CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll released at 6:23 P.M. on Friday, October 27, George W. Bush was proclaimed to hold a 13-point lead over Al Gore; in a CNN/Time poll released later that night at 8:36 P.M., Bush’s lead was calculated to be 6 points. When Huffington called the CNN polling director, he declared that the wildly divergent polls were “statistically in agreement … given the polls’ margin of sampling error.” The polling director explained that with a margin of error of 3.5 percent, either candidate’s support could be 3.5 percent higher or lower, indicating that a spread of as much as 20 points could qualify as “statistically in agreement,” thus...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction: Media Spectacle and Politics in the Contemporary Era

- Chapter 1: Grand Theft 2000: Media Spectacle and a Stolen Election

- Chapter 2: Spectacles of Terror and Perpetual War

- Chapter 3: Preemptive Strikes and the War on Iraq: A Critique of Bush Administration Unilateralism and Militarism

- Chapter 4: Pandora’s Box: The Iraq Horror Show

- Chapter 5: Image Wars: Media Spectacle and Election 2004

- Chapter 6: Decision 2004: The War for the White House

- Conclusion: Salvaging Democracy after Election 2004

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author