eBook - ePub

Medic

The Mission of an American Military Doctor in Occupied Japan and Wartorn Korea

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Medic

The Mission of an American Military Doctor in Occupied Japan and Wartorn Korea

About this book

In the aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Crawford F. Sams led the most unprecedented and unsurpassed reforms in public health history, as chief of the Public Health and Welfare Section of the Supreme Commander of Allied Powers in East Asia. "Medic" is Sams's firsthand account of public health reforms in Japan during the occupation and their significance for the formation of a stable and democratic state in Asia after World War II. "Medic" also tells of the strenuous efforts to control disease among refugees and civilians during the Korean War, which had enormously high civilian casualties. Sams recounts the humanitarian, military, and ideological reasons for controlling disease during military operations in Korea, where he served, first, as a health and welfare adviser to the U.S. Military Command that occupied Korea south of the 38th parallel and, later, as the chief of Health and Welfare of the United Nations Command. In presenting a larger picture of the effects of disease on the course of military operations and in the aftermath of catastrophic bombings and depravation, Crawford Sams has left a written document that reveals the convictions and ideals that guided his generation of military leaders.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Medic by Crawford F. Sams,Zabelle Zakarian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Perimeter

As the Sturgeon lay tied to the dock, I stood at her rail with a member of the theater engineer’s staff wondering what extent of destruction awaited us in this great port and industrial city of Yokohama. With a population of over one million people, Yokohama had been one of the primary targets of our army air force raids. In 1941, Gen. Elmer Adler and other senior officers of the army air corps had predicted that if our bombers could only reach and destroy the industrial centers of the Ruhr in Germany, the Ploesti oil fields in Rumania, and the Yokohama-Tokyo area in Japan, then Germany and Japan would immediately collapse and the war would end. I had seen firsthand the destruction wrought by such bombing raids at targets in North Africa and the Middle East, in Europe, and in the Philippines. Somehow the predictions had not worked out.

As an island empire, Japan was supposed to be vulnerable to such strategy. Some held that if her ships could be sunk, her ports destroyed, and her industrial centers laid waste, there was no need to defeat her armies. Her cities were particularly vulnerable to fire because ninety-eight percent of her buildings were built of wood; by destroying these, her labor force, at least, would be dispersed, even if the factories were not knocked out. Subsequently, according to press reports we had received from home, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were credited as ending the Pacific war. Such reports were to be taken as proof of this theory, at least so far as Japan was concerned.

Months later, through study of Japanese records, interviews with top civilian and military leaders of Japan, and firsthand study and evaluation of damage and destruction and her remaining resources, a truer picture began to emerge. Once again the theory and popular wishful thinking turned out somehow to be in error. Japan had recognized her defeat when her armies were annihilated on Okinawa and in the Philippines, and had made overtures for peace through Russia, a neutral at that time, in May 1945, three months before the atomic bombs were dropped.

Man has been seeking an ultimate weapon with which to defeat his adversary without great risk to himself since the first primitive heaved a rock at his barehanded enemy before the fingers of that enemy could close around his throat. The first cutting edge of steel, gunpowder, high explosives, bombs, and now the unleashed power of the atom, have all been hailed, in turn throughout history, as the ultimate weapon for defeating an enemy without too great risk to self; yet, history records that the final decision for victory in every war, even in Korea in 1953, is determined by men struggling in the dust or the mire for some piece of ground, no matter how worthless that ground may appear to be at the time. Perhaps it is justified politically as a deterrent against war to play up the destructive power of each new ultimate weapon, as it has been done throughout history, is being done in the present controversy, and will be done in the future until the end of time, provided, of course, you do not frighten yourself and your own people more than you do your potential enemies. For those charged with the responsibility for the conduct of war or for provision of defense forces, however, to believe one’s own propaganda or to fail to study the lessons of history is another and very dangerous matter.

I had spent much of my career studying the history and causes of human casualties, both civilian and military, and the relative effectiveness of their agents, whether disease or weapons of war. I had studied the means through organized medical efforts necessary for minimizing casualties and, particularly, deaths. I had directed such efforts in other parts of the world. Now that the war had suddenly ended without an invasion, that part of our plans for taking care of our military casualties from such an invastion had come to a close. But what of the enemy casualties, both civilian and military, which we would find in this land? That was to be my responsibility as chief of the Health, Education, and Welfare Division of the Military Government Section of General Headquarters, U.S. Army Forces, Pacific.

How accurate were our estimates of those casualties in the homeland from our air attacks, naval shelling, and the atomic bombs? How many military casualties were in hospitals? We had thought that very few had been evacuated from the Pacific Islands to Japan. What about epidemics? What medical facilities, personnel, and supplies remained in Japan?

I had learned through experience to make some correlation between physical destruction in cities and human casualties among the population. As soon as I could go ashore in Yokohama, I hoped to find some indication of the problems with which I would be faced. I had to re-evaluate our plans as quickly as possible in order to modify our requirements for medical supplies and relief supplies of food, clothing, blankets, and other items. Messages would have to be sent to the War Department so that only such quantities as would be required were shipped and the procurement of the sizeable quantities of such supplies that had been programmed were cancelled. All of these thoughts were running through my mind as I stood at the rail of the Sturgeon studying the scene around me.

As we surveyed the waterfront, the docks and warehouses appeared to be undamaged, although far to the north a Japanese aircraft carrier lay canted in a shipyard. No other ships could be seen. To the south, the New Grand Hotel facing the promenade along the waterfront also appeared to be intact. Just beyond the New Grand, the bluffs rose sharply along the shore, and we could see a number of fine homes that were also undamaged. These were the homes of the prewar foreign national colony, which subsequently were to serve as quarters for senior officers of the Eighth Army headquarters. On the skyline to the west we could see a church that had apparently been gutted by fire.

Directly opposite our ship was the customhouse. It was undamaged. We were especially interested in that building because it was to be the location of advanced General Headquarters of which I was a part. The building of reinforced concrete was painted black. We were to learn that all of the important buildings, governmental or private, including hospitals, had been painted black by the Japanese in an effort to make them more difficult to see during our night bombing attacks.

Something about this building appeared to be odd. It was constructed with several setbacks and a signal tower with numerous outside concrete stairs. My engineer companion called my attention to the fact that all of the steel railings and supports of the stairways had been removed. The steps for the stanchions were set in the concrete, but no other metal was apparent. We were to find throughout Japan that all metal had been removed from structures of all kinds. Even the steam radiators had been taken out of the buildings and piled in vacant lots preparatory to being moved to the steel furnaces as scrap.

Here, then, was the first indication of one of the causes of Japan’s defeat. Although in 1931 she had begun the development of an industrial empire in Manchuria, where there were tremendous natural resources, including iron ore and coal, and had for some years before the war been stockpiling scrap steel from all over the world, particularly from the United States, Japan had virtually exhausted her supplies of scrap. She had resorted to stripping every available pound of metal that could be gotten from her buildings, bridges, and factories.1

Shortly after the gangplank had been lowered, we were called below for a staff conference and orientation. A perimeter would be established around Yokohama when sufficient troops arrived. In the meantime, we would not leave the perimeter area. We could go ashore but must always go in pairs. Side arms were to be worn at all times. We were to avoid any incidents with Japanese we might encounter. Those who so desired could move into the New Grand Hotel, but the Sturgeon would remain at dockside to serve as billets for an indefinite period. We would proceed to set up General Headquarters in the customhouse using field tables, chairs and other field equipment as soon as it could be unloaded from the ship. It would be days before vehicle transportation would be unloaded from ships en route from the Philippines, so we would be on foot until that time.

The Customhouse

Brig. Gen. William Crist, chief of the Military Government Section, and I debarked and started the short walk to the customhouse. As we left the dock, we encountered two Japanese national policemen with their helmets and short swords and one American soldier of the Eleventh Airborne Division, who were guarding the entrance to the dock. They were the only living beings we could see in what appeared to be the remains of a dead city.

The prefecture building, a large brick building painted black and set in a block-square park, was intact. A few other brick or concrete buildings to the south were intact. These included a large department store, which we would later use as a military hospital. To the west we could see a few isolated concrete buildings obviously gutted by fire. The rest of the scene was one of desolation. I had become accustomed to destroyed or damaged cities in other parts of the world and to the sight of huge piles of rubble of brick or stone from well-supported buildings that had collapsed under bombing, shelling, and demolition. Here there was no such picture—only ashes—literally miles of ashes interspersed with tall, isolated brick chimneys and steel safes. Later I learned that the chimneys were the remains of public bath buildings, which had dotted every Japanese town and city.

The steel safes were the result of lessons learned in the 1923 earthquake and fire. After that disaster in this land of major disasters, great difficulty had been encountered in settling insurance claims as records and policies had been burned. When the Tokyo-Yokohama area had been rebuilt, a campaign had been undertaken to sell steel safes to all who could afford to buy them. The campaign had evidently been a success for I had never seen so many safes. Although the people had lost their homes and their possessions, this time, at least, they had their safes and policies and records.

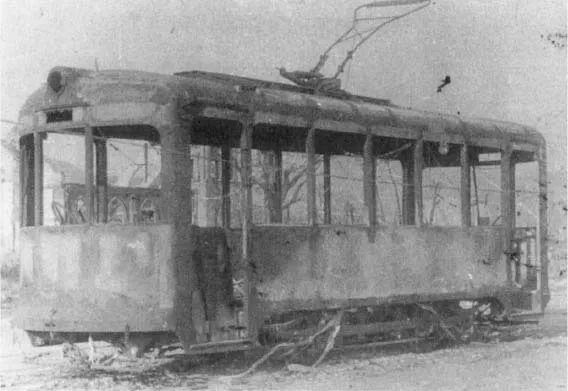

The streets were passable but for an occasional burned-out streetcar, truck, or fire truck that had been engulfed by the fire storms. No passenger cars could be seen burned or abandoned in the streets. Broken trolley wires and power lines dangled across streets and walks, serving to menace the unwary passerby in the night in a city without lights. Thousands of burned bicycles lay in the ashes or along the streets in mute testimony of the speed with which the flames had swept the city. To the north, we could see the twisted skeletons of burned factories and mills. The heat had been so intense that massive steel girders and pillars looked like a writhing mass of reptiles flung to the ground by the hand of a giant.

But what of the people in this great ghost of a city? Nothing moved, there was no sign of life. There was a deathly silence. Had they all been consumed in the holocaust? Because my concern is primarily with people, I wondered as to the fate of those caught in the storm of fire.

Fire storms of such magnitude have never been seen in Europe or America, where our cities of different construction and design do not provide the tinder of a Japanese city. It was not until I had witnessed the second burning of Aomori in northern Honshu a year later that I could visualize what had happened in Yokohama. The endless blocks of closely packed, frequently interconnected frame buildings serve as a powder train through which the flames sweep with ever increasing speed and intensity, creating their own winds of cyclonic force. So strong are they that one can hardly stand upright. The flames fed by these winds increase to such intensity that buildings are consumed with the force of an explosion.

Figure 1. An occasional burned-out streetcar such as this one was part of the desolate scene that occupation forces encountered in Japanese cities that had been engulfed in fire storms during the war. Occupation of Japan, circa September 1945. (Courtesy of the Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University.)

Figure 2. The Yamato Department Store, once an imposing seven-story building, was reduced to a mass of twisted steel and concrete by the intense heat of fire bombs during the war. Occupation of Japan, circa September 1945. (Courtesy of the Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University.)

At frequent intervals between the curbs and the sidewalks were slit trenches in which people evidently sought refuge when an air raid alert sounded. They offered protection against bomb fragments and flying debris, but, as I was to learn, throughout Japan many people were found dead in these shallow trenches, which had become their coffins. There was no mark upon them, for the cyclonic winds of the fire storm literally sucked the air from these trenches as the fire swept past, and the people died for lack of oxygen. It was something to remember for the future.

The tall steel structure of the Tokyo and Yokohama elevated electric line appeared to be undamaged. At the railroad yards near the station, the tracks had been repaired. A few four-wheeled freight cars, characteristic of European and Japanese railroads, were in the yards. Some were burned. The few modern, double-trucked passenger cars in the yards looked like sieves from machine gun bullet holes of strafing raids. These raids must have been carried out by carrier based aircraft, as army fields for tactical aircraft used in low-level strafing were too far away for such attacks when the war ended.

As we entered the customhouse, we saw a picture that was to become all too familiar throughout Japan. The fine floors were covered with a scum of wax and dirt of several years’ accumulation. The walls were grimy with soot; they had obviously not been repainted during the war. The windows were almost opaque from the grime. The radiators had been removed as had all railings. Small single light bulbs hung suspended from cords in the ceiling. Blackout curtains were fixed to all windows.

After walking through the building, we finally located the room on the ground floor to which our staff section was assigned. There were a few old desks and chairs in the room, and I sat down at one that had a knee well. That was my first mistake in Japan, although far from my last. In only a matter of seconds, my ankles were on fire. They were covered with a swarm of culex mosquitoes, who had been resting in the cool shadowed recesses of the knee well. They were obviously starved for some fresh blood. They were not adverse to taking it from an enemy of Japan, and they were not willing to wait until the usual biting time at dusk. This was a bright sunny midmorning.

I had hoped to find some indication of the nutritional status of the Japanese people, for one of my responsibilities was to make such determinations and recommend importation of food for relief purposes, if necessary. Yet my first contact with living creatures in Japan was with insects, who from their actions appeared to be starving. The Japanese had never attempted modern methods of insect control and had no such thing as DDT, which had been so effective in malaria and fly control throughout the world during later years of the war; thus, one of my first tasks would be to obtain DDT and sprayers from my friends in the navy. All buildings to be occupied by our people would have to be given a thorough spraying before we could use them.

The Police Hospital

As our field equipment for the office had not yet been unloaded from the ship and there was nothing yet to be done in the customhouse, I set out on foot with a Nisei interpreter on a reconnaissance of the city. I hoped to locate a hospital in order to form some idea of the medical situation and the work ahead. I had a prewar map of the city, but the widespread destruction made it difficult to identify landmarks. The map, however, showed a small police hospital located near the New Grand Hotel. There were a number of undamaged buildings in that area, including the Helm House apartments, so we proceeded in that direction.

As my interpreter and I walked down the street, we located a painted brick building, which from its location and color should have been the hospital. We entered the lobby, and my interpreter called out in Japanese to learn if anyone was present. Silence greeted us. We then began a tour. It was even more filthy than the customhouse. In the laboratory, drawers were half open; broken equipment was strewn about the floor and tables. In the X-ray room, we found a machine of Japanese manufacture patterned after German machines I had seen in captured German military hospitals in North Africa and Europe. The machine appeared workable, but there was no electricity and no standby electric power generator such as we routinely have in our hospitals. I was interested in the quality of technical work done by the Japanese, which could be judged by an examination of films. To my surprise there was no film. X-rays had been taken on photographic paper, which had a coarse emulsion, so the films were fuzzy and difficult to read. Later I learned that no Japanese hospital had X-ray film during the last three years of the war.

In the operating room, there were only pa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- Chronology of Sams ‘s Life and Work

- Dedication

- Preface

- The Move

- Japan

- Korea

- Coming Home

- Notes

- Appendix I: Editorial Decisions

- Appendix II: Photographs

- Index

- About the Editor