![]()

PART I

Inclusive dance pedagogy

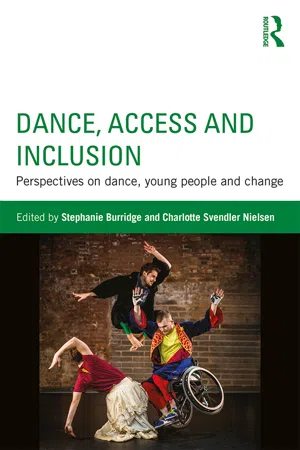

PHOTO The Dance Laboratory (Norway)

Dancer: Mari Flønes

Choreographer: Tone Penille Østern

Photographer: Jøran Værdahl

![]()

1.1

MAKING NO DIFFERENCE

Inclusive dance pedagogy

Sarah Whatley and Kate Marsh

Introduction

This chapter discusses how developing a range of pedagogical strategies ensures that dancers of all abilities can access dance in further and higher education, as a preparation for a professional career in dance. Beginning with an overview of some of the factors that have shaped an inclusive dance pedagogy, and a discussion on the terminology that has supported or inhibited inclusion, the chapter will describe actions for best practice within the dance studio, where dancers with and without disabilities can lead, learn and develop together. We will examine the merits of adaptation and translation, and outline the principles behind a range of teaching methods illustrated through examples of activities. Evaluative commentary will discuss the effectiveness or otherwise of these approaches in removing perceived barriers to participation for those with different abilities. We argue that rethinking and adjusting teaching and learning methods to accommodate differently abled dancers results in better experiences for all dancers, calling for a radical pedagogy that promotes equal access to dance as a route into professional practice.

Access and inclusion

Accessing a training course in dance at a further or higher education level is always more challenging for dancers with disabilities. These challenges result from perceptions that are held by all involved in the individual student’s journey: the educational institution and teaching faculty, career advisers, family and friends, and the student him- or herself. It is perhaps surprising that in the twenty-first century there is still some way to go before barriers to participation are dissolved and our dance training programmes are fully accessible to talented and motivated students. Many dance curricula do not overtly discriminate against the differently abled dancer but that does not always mean that the curriculum is accessible, appropriate and inviting to those students who may perceive themselves to be discriminated against. Moreover, there continues to be anxiety amongst many who design and teach courses in dance about how to accommodate and support disabled students.

The common perceptions of who can and should be able to access dance training need changing if disabled students are to feel able to apply for courses, can learn in an inclusive environment and can be role models for others to follow. The prejudices that still lurk, often unspoken, in the dance studio and are re-inscribed in the ‘perfected’ dancing body in the name of ‘excellence’ and ‘quality’, and which persist through an aesthetic of similarity coupled with flawlessness, grace and elegance, do no service to any dancer, disabled or non-disabled, and neither do they move the art form forwards. There are dance artists who challenge this very successfully in their work. Catherine Long, for example, in Impasse (2014) consciously explored an aesthetic of awkwardness and the ‘monstrous’, which set out to challenge the fear of loss, of not being ‘whole’ that is associated with disabled dance.1 But Long’s work is not yet penetrating the institutions that preserve a dominant dance aesthetic that is blind to diverse dancing bodies. Long demonstrates that every dancer has the potential to develop a unique virtuosity worthy of value and praise. Moreover, differently abled dancers show how no bodies are static; we are all unique and all in transition, gaining and losing functions, and capacity for movement. An aesthetic grounded in inclusion would facilitate the shift that has been called for in the “discourses of legitimacy” (that still marginalise the bodies and artistic contributions of disabled dancers) (Irving & Giles, 2011).

Building a diverse student community in a dance training environment requires a strong inclusive ethos but the emphasis on dancers developing a virtuosic technique, predicated on a normative aesthetic, privileges some dancing bodies over others. The dance training environment can therefore fuel ‘ableism’ and ‘disablism’, whereby ‘ableism’ is associated with the perfect body, designating disabled people as inferior to non-disabled people, reinforcing bias and discrimination, and which a radical approach to teaching dance tries to resist. However, there are unavoidable realisms to this resistance. Students with any physical, sensory or cognitive impairment are frequently in a tiny minority within a dance programme. Often, if the only student in a cohort of non-disabled students, in a context that is traditionally built upon homogeneity of body types rather than heterogeneity, a student who is differently abled is hypervisible. Moreover, non-disabled students are usually unfamiliar with the experience of dancing alongside and working with students with disabilities so careful orientation and induction is needed for all students, particularly if the disabled student needs assistive technologies in the studio, such as wheelchairs or seeing dogs, etc. Another challenge lies in the indivisibility of the dancer’s body from the dance, presenting something of a paradox. If the dancer’s disability is visible then disability is once again made hypervisible; disability becomes performative and hence the familiar condition of the disabled person always ‘performing’ their disability (Garland Thomson, 2009). Conversely, if the disability is unseen, then the dancer may find herself treated no differently than any other non-disabled students. Whilst full integration may be desirable the absence of any appropriate adaptation or mitigation may present different problems.

Rethinking the teaching of dance ‘technique’

Technical training continues to be a main strand of activity within a dance programme and this often calls for the dancer to work towards a ‘neutral’ body – stripping away prior learning and privileging the natural, which tends towards essentialising the normate dancing body. But assuming there is a neutral body is problematic and the disabled dancer with a unique body or impairment will find little relevance in a course of study that promotes the acquisition of a flawless and “multipurpose hired body [that] subsumes and smooths over differences” (Foster, 1997: 256). The dancer will also need to find an individual approach to technical development and may come with little or no prior learning on which to draw whereas most non-disabled students come from an experience of mainstream education and with prior experience of what it means to learn in a dance context – the format of class, the etiquette, behaviour, etc. – so there is already an imbalance in the studio, the primary learning space for the dancer. Consequently, including students with disabilities takes time, resources, willingness and systems in place (such as Learning Support Assistants [LSAs]) to provide the right level of support for each student. If an LSA is to provide support then it works best if it begins from induction onwards, wherein all students learn the value of partnering and peer support and students with any impairments are given space to speak to their peers about their disability and their needs, if appropriate, including any ‘rules’ around a seeing dog or other aid in and around class. Importantly, by working together as creative collaborators throughout their studies, the interest in bodily difference as an exotic spectacle (Mitchell & Snyder, 2006: 157) is diminished.

Building an inclusive learning experience is therefore dependent on the employment of particular teaching strategies to accommodate the different physicalities and abilities of the students. But despite what is inscribed in law, specifically the 2001 Special Educational Needs and Disability Act, that education providers have a duty not to treat disabled students less favourably and a duty to make reasonable adjustments to ensure that people who are disabled are not put at a substantial disadvantage compared to people who are not disabled, there remain barriers for disabled dancers entering training programmes, sometimes due to reluctance on the part of the institution to make the necessary adaptations and adjustments.

Where teaching, learning and assessment methods have been considered and perhaps adjusted to ensure compliance, tutors have recognised that changes that are made for the disabled students are frequently positive for all students. An accessible dance curriculum is about good course design, good teaching and assessment methods and a student-centred approach to all aspects of course delivery.

Thus far, we have referred to ‘inclusive’ or ‘integrated’ dance as descriptive ‘labels’, and ‘translation’ and ‘adaptation’ as teaching strategies. These terms are often contested, as are the wider labels and categories that persist within the discourse on dance and disability. Indeed, the language used to describe, discuss and represent disability has a history of dividing opinion. The etymology of key words and phrases associated with impairment gives an insight into shifting perceptions of disability over periods of history. The term ‘Handicapped’, widely rejected in current UK discourse, holds negative connotations and has been rejected, in particular, by individuals and organisations championing the rights of people with disabilities. A brief inspection of the history of this term indicates that it is synonymous with themes of burden or carrying extra ‘weight.’2 ‘Inclusion’ is a label that often defines a mode of working, viewing and interaction, but which is not always helpful to those involved. But both ‘inclusive’ and ‘integrated’ are terms frequently used within the professional dance context to signal where disabled people work alongside non-disabled people. Inclusion as a mode of working and thinking can be implicit in the dancers’ working environment. Working methods can vary widely but at the core is an interest in exploring both common ground and individual difference. Set within a broader context of an inclusive ethos, the label ‘inclusive’ thus suggests a relational aesthetic, which can be empowering (feeling part of an inclusive ‘movement’) or it might limit judgment and openness to what is being viewed. Inclusion is therefore a fluid term that benefits from continual questioning so that the terms ‘inclusion’ and ‘inclusive practice’ are used or applied thoughtfully and knowingly, acknowledging the situatedness of the term and its implications. An inclusive label also avoids any erasure of or making invisible disability but may draw attention to disability rather than emphasising the dance. Related to the label ‘inclusive’ is the real distinction between disability and impairment, which points again to the complexities of terminology. Consequently, there is considerable debate about the positive and negative aspects of these terms but as they continue to be in common circulation within the sector they are terms used to point to the fundamental philosophy of equal participation.

Disability versus impairment

It is generally acknowledged, following the social model of disability (Finkelstein, 1993)3 that disabled dancers are dancers with impairments who are (more accurately) disabled by the environment and structures in which they live, so ‘disabled dancers’ is somewhat unhelpful; it promotes the objectification of a group of people and reinforces the categorisation of disabled people as ‘other’. The term non-disabled refers to the artists who have not disclosed any disability but it can imply a binary between one group and another. Dancers with disabilities sometimes choose to describe themselves as ‘differently abled’, but any label is contingent, imprecise and can infer allegiance with an objectification of a group of people. Whilst care with language is important, some dancers will feel proud of a disability label. The term can offer a sense of belonging to a wider community, which can be empowering; a community which finds form within the dance sector as well as within the wider context. The unpacking of terminology and its associated meaning and interpretation has been and continues to be central to the rights and voices of people with a disability or impairment.

There is also a valid discussion to be had around ‘disabled’ versus ‘impaired’. Mike Oliver offers a useful definition of impairment as “individual limit...