eBook - ePub

Hospitaller Piety and Crusader Propaganda

Guillaume Caoursin's Description of the Ottoman Siege of Rhodes, 1480

- 394 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hospitaller Piety and Crusader Propaganda

Guillaume Caoursin's Description of the Ottoman Siege of Rhodes, 1480

About this book

Guillaume Caoursin, the Vice-chancellor of the Order of the Hospital, wrote the Obsidionis Rhodiae urbis descriptio (Description of the Siege of Rhodes) as the official record of the Ottoman siege of the Knights in Rhodes in 1480. The Descriptio was the first authorized account of the Order's activities to appear in printed form, and it became one of the best sellers of the 15th century. The publication of the Descriptio not only fed Western Europe's hunger for news about an important Christian victory in the ongoing war with the Turks, it also served to shape public perceptions of the Hospitallers. Caoursin wrote in a humanistic style, sacrificing military terminology to appeal to an educated audience; within a few years, however, his Latin text became the basis for vernacular versions, which also circulated widely. Modern historians recognize the contributions that the Ottoman siege of Rhodes in 1480 made in the development of military technology, particularly the science of fortifications. This book is the first complete modern Latin edition with an English translation of the Descriptio obsidionis Rhodiae. Two other published eyewitness accounts, Pierre D'Aubusson's Relatio obsidionis Rhodie and Jacomo Curte's De urbis Rhodiae obsidione a. 1480 a Turcis tentata, also appear in modern Latin edition and English translation. This book also includes John Kay's Description of the Siege of Rhodes and an English translation of Ademar Dupuis' Le siège de Rhodes. The lengthy introductory chapters by Theresa Vann place the Ottoman siege of Rhodes in 1480 within the context of Mehmed II's expansion in the Eastern Mediterranean after he captured Constantinople in 1453. They then examine the development of an official message, or propaganda, as an essential tool for the Hospitallers to raise money in Europe to defend Rhodes, a process that is traced through the chancery's official communications describing the aftermath of Constantinople and the Ottoman

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hospitaller Piety and Crusader Propaganda by Theresa M. Vann,Donald J. Kagay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Hospitallers and Rhodes

A Brief Description of the Order of the Hospital

The Order of the Hospital is a military religious organization that began as a pilgrim's hospice in the city of Jerusalem before the arrival of the First Crusade in 1099. The Order received papal recognition in 1113 and assumed military responsibilities for the Christian states in the Latin East during the twelfth century. Like the Order of the Temple, the Knights of the Hospital (or Hospitallers) defended pilgrims and the Latin settlements in the east. The two Orders became international corporations headquartered in the Latin East that received grants of property in western Europe in addition to their lands in the Levant. An essential difference between the Hospitallers and the Templars, however, was that the Hospitallers operated a large hospital for the sick and pilgrims at their central convent and dedicated a substantial percentage of their revenues for its upkeep. After the last Latin outpost in the east, Acre, fell in 1291, both the Templars and the Hospitallers relocated their central convents. The Templars withdrew their headquarters to France, where in 1307 Philip the Fair of France outlawed the organization and its members, putting many of them on trial; by 1312 Pope Clement V suppressed the Order. The Hospitallers remained in the eastern Mediterranean, spending a brief period on Cyprus and undertaking the conquest of the island of Rhodes, which they completed by 1310.1 The Order located its central convent within the city of Rhodes, free from the jurisdiction of any temporal or diocesan power other than the papacy. The decision to conquer Rhodes and to establish the central convent there was an important factor in the survival of the Order of the Hospital, and enabled it to evolve as a sovereign entity on Rhodes and later on Malta.

The essential governmental structures of the Order of the Hospital were already established when it arrived at Rhodes. The head of the Order, the master, was elected for life. His advisors, who formed part of the master's council, were the chief officials of the Order: the conventual prior, the grand preceptor, the hospitaller, the marshal, the admiral, the turcopolier, the draper, and the grand bailiff, hi addition to his council, the master could summon the chapter general to meet at Rhodes. The chapter general was the general assembly of the Order, which discussed major issues such as finance, legislation, and warfare.2 The attendees of the chapter general were the master, the senior members of the order, its chief officials, and two representatives from each priory. According to statute, the master had to call a meeting of the chapter general at least once every five years, but it could meet more frequently if the master thought it necessary. At the meetings of the chapter general, the master and the chapter heard petitions and generated decisions, edicts, and statutes that were binding upon all the members of the Order.3

The members of the Hospitaller Order living on Rhodes were Europeans who had joined the Order in one of its priories in France, Spain, Germany, Italy, or England. They had been accepted into the Order as either a brother, chaplain, or knight. All had taken vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to the master. Most men joined the Order as serving brothers, who performed a variety of tasks, or as brother sergeants-at-arms, fighting men of free, but not necessarily knightly, birth. The knights, who with the sergeants-at-arms fought 0n behalf of the Order, held all the high offices of the Order. Although they did not have to "prove" their nobility until a later period, a candidate had to be of legitimate, knightly birth. Knights had higher status than the chaplains, the ordained priests who tended to the spiritual needs of the members of the Order. Women could join the Order, but they remained in European convents; they did not serve in the Order's hospitals or fight in its battles.4

The Hospitallers of Rhodes received income from their estates in the eastern Mediterranean (including sizeable properties on Cyprus, some formerly belonging to the Templars) and collected revenue from the coastal trade that passed through their harbors. The Order organized its properties in Europe and in the eastern Mediterranean into the units of commandery, priory, and langue. The commandery, usually an estate, was the basic unit of Hospitaller property. It provided a benefice for a knight or a sergeant-at-arms, and also contributed to the yearly dues, called responsions, that each priory paid for the support of the central convent. The priories were larger administrative units that consisted of a number of commanderies, organized by region and headed by a prior. At some point before 1310, the Order organized its priories according to langues (also called "tongues" or "nations"). The knight's place of birth determined his langue affiliation. Initially there were seven langues: St. Gilles (or Provence), Auvergne, France, Spain, Italy, England (which included Ireland, Scotland, and Wales) and Germany. In 1462 the Order divided the Spanish langue into two parts, Aragon and Castile.

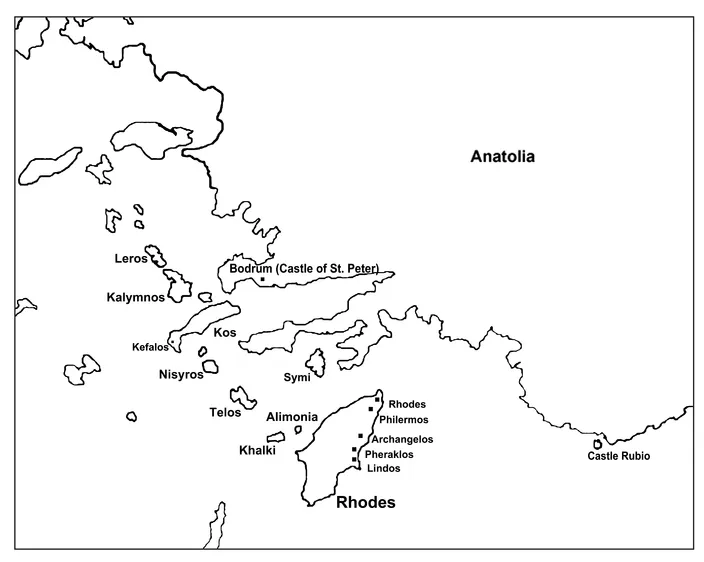

Figure 1.1 Map of Rhodes in the Eastern Mediterranean, showing Hospitaller possessions in the Dodecanese. (© Theresa Vann)

By the fourteenth century, the chief offices of the Order were assigned by langue, except for the conventual prior, who supervised the conventual chaplains.5 The bailiff of Province traditionally held the office of grand preceptor, who functioned as the master's second-in-command. The bailiff of France held the office of the hospitaller, who ran the infirmary. The bailiff of Auvergne was the marshal, or chief military officer. The bailiff of Italy was the admiral, who commanded the fleet of the Order. The bailiff of England was the turcopolier, who commanded mounted mercenary troops. The bailiff of Aragon was the draper, who originally issued clothing, fabric and alms and later provisioned the Order's military forces. The bailiff of Germany held the office of grand bailiff, overseeing the fortifications of outposts such as the castle of Bodrum.6 When Master Pedro Raimundo de Zacosta created the langue of Castile in 1462, he elevated the office of the chancellor to a seat on the council, where it became the bailiwick of the new langue.

A Brief Description of the Island of Rhodes

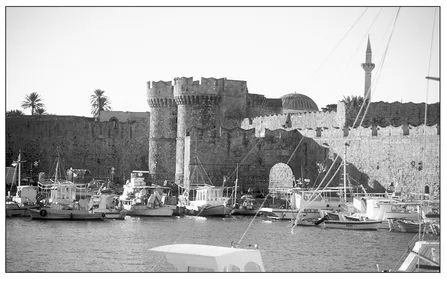

Figure 1.2 The Marine Gate, Rhodes. (Photo: Theresa Vann)

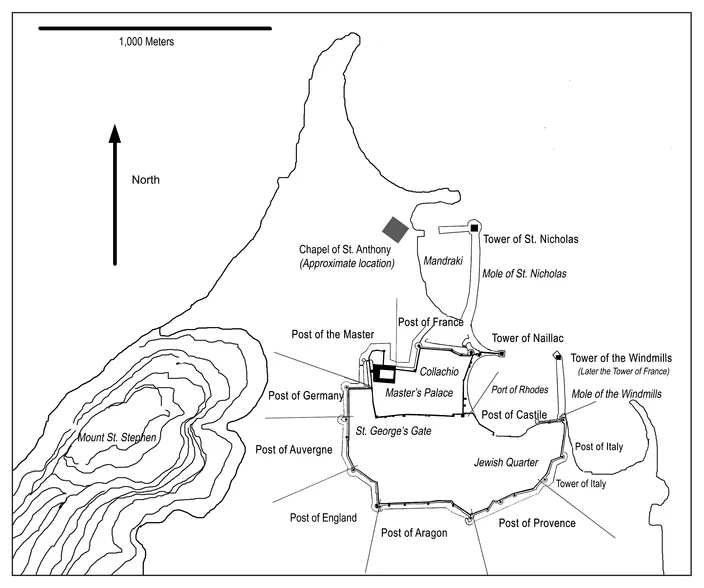

Rhodes is one of a string of islands that lies off the coast of eastern Anatolia in the Aegean Sea. Culturally, medieval Rhodes was a Greek island, nominally part of the Byzantine empire until the Hospitallers captured it. The crescent-shaped city of Rhodes, famous in ancient times as the site of the Colossus of Rhodes, is located on the northeastern end of the island. It encircles a natural harbor, divided by three artificial moles into two smaller anchorages. These moles, considered of "great antiquity" in the fifteenth century, created a small harbor (the Mandraki) for the galleys of the Order and a larger, commercial harbor for trade. The Order built three towers on the ends of the moles to defend the port: the tower of the Windmills (also known as the tower of St. Peter and later, the tower of France) on the mole of the windmills; the tower of St. Nicholas on the mole by the Mandraki, and the tower of Naillac on the mole separating the two. The Order slung a chain between the moles to protect the harbors.7 In addition to the city of Rhodes, the Hospitallers built and maintained a complex system of watchtowers and strongholds throughout the island.8

Modern Rhodes is still encircled by medieval walls, but the present day visitor looking for the landmarks of the siege will have a difficult time finding them. The siege of 1480 and the earthquake the following year altered the topography of the city. In addition, the Order pulled down many churches near the walls immediately after the siege. One of these was the chapel of St. Anthony; the modern Latin church standing on the spot today is believed to be in the approximate location of the earlier structure. D'Aubusson rebuilt and augmented the walls after the 1480 siege, and much of the current arrangement of gates and towers dates from between 1481 and 1522, During the Ottoman occupation the Turks recycled Christian monuments and the identification of many churches and inns became disassociated from their sites. Nineteenth-century earthquakes changed the profile of the tower of St. Nicholas and destroyed the tower of Naillac, which had a distinctive circular lookout located on each one of its top four corners. An explosion of unknown origin in 1856 destroyed the conventual church and severely damaged the magisterial palace. The conventual church was not rebuilt, although portions of its foundations remain and fragments from it may be identified in other buildings in the old city of Rhodes. The magisterial palace that visitors see today was recreated by Italian architects in the 1930s on the remains of the original structure. Over the centuries the fosse filled with garbage and Ottoman cemeteries were located outside the walls of the city. The cemeteries remain; in the late twentieth century, the fosse was cleared of garbage and reborn as a public park. The new city of Rhodes now surrounds the old city, overlaying the location of the Turkish camp during the siege.9

Figure 1.3 Map of the city of Rhodes and its surroundings. Adapted from Albert Gabriel,La cité de Rhodes: MCCX-MDXXII, 2 vols. (Paris, 1921–1923).

In the fifteenth century, the statutes of the Order required its members to live in the collachio, a separate walled quarter within the walls of Rhodes. Each langue maintained an auberge, or inn, which provided accommodations for visiting knights; knights resident in Rhodes did not necessarily live in community. The modern visitor enters the collachio through the Marine Gate, walks past the "new" infirmary (completed after the 1480 siege) and up the "Street of the Knights," which is lined with restored auberges. At the top of the street, on the site of the Byzantine citadel, the restored magisterial palace sits within its own walls at the highest point of the city. Opposite the palace stand the ruins of the conventual church. A line may be drawn from the tower of St. Nicholas through the collachio up to the magisterial palace. By focusing their assaults upon the tower of St. Nicholas, the Turks could control the harbor and obtain a base to attack the collachio and the magisterial palace. When the assault on the tower of St. Nicholas failed, the Turks concentrated on the weakest segment of the city's fortifications, the walls alongside the Jewish quarter of Rhodes, which lacked towers or bastions. Even if the Turks had taken this sector successfully, they still would have had an uphill battle for the collachio and the magisterial palace, since the Jewish quarter was located in the lower part of the city. The exact location where the Turks breached the walls was commemorated in 1489 with the construction of a church on the site; recent archeological excavations have uncovered its foundations.10

Caoursin's Descriptio told little of the appearance of the island and city of Rhodes. It named places that proved important during the siege: the mountain of St. Stephen, from which the Rhodians first sighted the Turks; the Ottomans' landing site, at the foot of the mountain; the enemy camp at the church of St. Anthony (now demolished), located outside the walls; the tower of St. Nicholas, located at the head of the long mole; the place on the city walls where the Turks launched their first foray; the fosse at the magisterial palace, where the traitor Master George first presented himself to the Hospitallers; the tower of St. Peter, which lay in front of the Mandraki; the chapel of the Virgin of Mont Philermo (located outside the city walls); the wall of the Italian station; the church of St. Mary Misericordia; the wall of the Jewish quarter; the Street of the Jews; and the harbor.

D'Aubusson's...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- 1 The Hospitallers and Rhodes

- 2 Danger from the Great Debt and the Great Turk, 1453–1480

- 3 The Genesis of the Descriptio

- 4 Guillaume Caoursin, Descriptio obsidionis Rhodiae

- 5 Pierre d’Aubusson, Relatio obsidionis Rhodie

- 6 John Kay, Description of the Siege of Rhodes

- 7 Ademar Dupuis, Le siège de Rhodes

- 8 Jacobo Curte, De urbis Rhodiae obsidione a. 1480 a Turcis tentata

- Appendix: Selected Magisterial Bulls

- Bibliography

- Index