![]()

1

PUBLIC SCHOOLS AND THE CRIMINALIZATION OF DIFFERENCE—DESTRUCTION AND CREATION

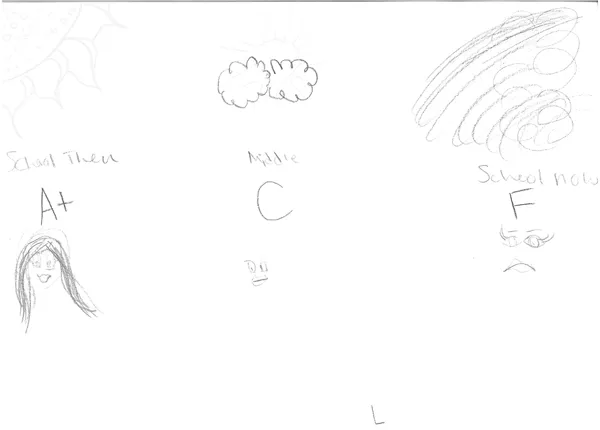

As Tristen1 and I sat in the cafeteria at Hull House, a maximum-security center for girls, often called Hull by students and staff, I could see the cobalt blue sky and open expanse outside the window. The barbed wire fence cut through the bucolic scene, however, and was a constant reminder of the limitations of environmental beauty. Tristen, a tall 15-year-old Black girl who smiled often, talked to me about how her feelings about school shifted over time,

I was a good kid…2 Until I got into Middle School. I just fell behind in all my subjects…. I kept on moving around so I fell behind then I just quit. Because everywhere you go, they’re on different things. And I got switched around too many places so I just fell behind.

Tristen’s Education Journey Map (Figure 1.1) contained a common narrative of the girls in this book. Many began fairly successful in schools, but as they progressed, they began to struggle for a variety of reasons, until they eventually failed to succeed in prison nation.

In this chapter I throw open the doors of public schools and bring us inside the girls’ lives. Because marginalized identities are not interchangeable and multidimensional oppressions are contingent on the historical, social, political, and economic contexts (Yuval-Davis, 2006), it was essential to explore them. Therefore, I focused on how the institution of school shaped and responded to girls and their actions and situated the girls’ narratives in context. Though public schools were not always the direct cause of multiply-marginalized dis/abled girls of color becoming part of the juvenile incarceration system, public schools were the sites where their struggles and criminalization were on display. According to education scholar Gloria Ladson-Billings (2006), the education debt is a sum that we owe children of color which has accumulated over time and fuels the persistent racial inequities in schools. Drawing from Brenner and Theodore (2002), I argue that this debt is perpetuated through a cycle of destruction and creation that multiply-marginalized girls of color experienced in schools.

Brenner and Theodore (2002) note, “The concept of creative destruction is presented to describe the geographically uneven, socially regressive, and politically volatile trajectories of institutional/spatial change” that occur at multiple geographic scales (p. 351). The authors provide an example of this destruction at the spatial scale of urban cities. They argued what was destroyed through policies and practices was a city wherein all were “entitled to basic civil liberties, social services, and political rights” (p. 372). They state that what was created in replacement of these was:

• Mobilization of zero-tolerance crime policies and broken windows policing.

• Introduction of new discriminatory forms of surveillance and social control.

• Introduction of new policies to combat social exclusion by reinserting individuals into the labor market (p. 372).

When the scale is shifted from the larger city that Brenner and Theodore describe down to the micro-interactional level, following I illustrate how this cycle of destruction and creation exists within the education trajectories of multiply-marginalized dis/abled girls of color. What we witness in this chapter is the ways girls’ access to education, resources, and the benefits of attaining an education were destroyed through systemic divestment. That is, schools and the school personnel within refused to engage their time, energy, or resources to allow girls access to high-quality education, and this divestment was destruction of their access to education. Moreover, this destruction was accompanied by a creation, a commitment to new infrastructure, which was the building of a criminal identity for the girls (Brenner & Theodore, 2002). In this chapter we witness how school begins as a respite for many of the girls, but through creative destruction—the processes in which white supremacist ableism actively removes resources from multiply-marginalized dis/abled girls of color—public schools criminalize difference in a prison nation.

School as a Respite

It is often falsely assumed that children are automatically at risk because they are of color, lower socioeconomic status, or have a dis/ability; this suggests that because children are located within particular social identities, students will immediately be disconnected from school because they do not value education (Harper & Davis III, 2012; Ladson-Billings, 2014; Valencia, 2002). However, the girls’ lives outside of school were complex and difficult to navigate, and therefore many of them looked forward to school. For seven of the girls, at one point in their lives school was a respite, a welcome reprieve from home, neighborhood, or other facets of life. They associated school with safety and even fun. Myosha, a 16-year-old Native girl who was often serious, declared that school was an oasis from her chaotic home life due to specific teachers.

I really liked that school…She was really like understanding. We had like this thing that was called the star of the week where they cut out this star and put your picture in the middle and all the students wrote something about you and like made a book. It was like her own thing that she made for us and each week they pick someone different for the star of the week….I liked her class a lot.

Myosha recalled how school made her feel special when teachers focused on and supported her as an individual.

Nashawna, a 14-year-old Black girl who had a two-year sentence in front of her, told me enthusiastically how school used to be fun for her, “I loved elementary school.” When I asked her what she loved about it, she gushed, “Everything like recess, going, talking, learning, learning experiences were fun, teachers were actually hands on.” What is important to note from the outset is that these girls did not automatically arrive at school prepared to hate it, even though all were dis/abled and of color. The disconnect that occurred later was created. In other words, some assert that these children embody identities that will be naturally problematic in schools. This is encoded in terms like “at risk” (Whiting, 2006). However, it is this assumption that is problematic. Many of these multiply-marginalized dis/abled girls of color did not come to school with resistance to education or learning and in fact loved school.

Instead the girls repeatedly described an institutional absence and the weight of responsibility they carried to fill those absences. Moreover they noted that the ways schools responded to that weight of responsibility often aggravated their issues, making school less enjoyable and the girls’ lives more difficult to manage. This creative destruction through systematic divestment occurred outside and inside public schools, wherein resources were actively diverted from girls because of their difference from the desired norm, which made them more susceptible to criminalization.

The Weight of Institutional Absence

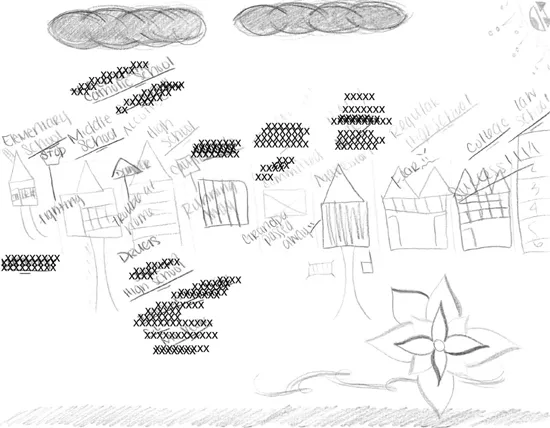

Myosha and I are leaning over her Education Journey Map (Figure 1.2) so I can see the words written within the image as she narrates her education journey. She says, “(A)nd that sign is a danger one and it says trouble at home….I’ve been committed for, um, running away, fighting.”

We talk about making a map for other girls who were in her previous situation, running away and fighting, before incarceration. I ask, “Do you think they should be locked up or what else could we do for them to help?” Myosha replies,

I think that somebody should just take the time and sit down and talk with them and find out what’s wrong and not just push them away. If they get frustrated, figure out what’s really wrong with them, not just throw it aside, I guess.

I follow up, “Do you feel like anybody did that for you?… Is that something you needed?” Myosha shakes her head no at the first question and then says, “Yeah, I needed more help.”

Myosha illustrated the need for more resources and supports in public schools. Like Myosha, many of the girls and their families experienced the weight of institutional absence; they did not have access to societal institutions. These multiply-marginalized dis/abled girls of color experienced a lack of childcare, health care, and even security in the form of police protection—all institutions that exist in the lives of the majority of Americans.3 Additionally, as is becoming increasingly well known, many incarcerated girls have histories filled with interpersonal violence (Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal, & Vafa, 2015). What we found was that violence directly impacted the ways the girls experienced public school; moreover, that violence was not simply interpersonal, girls also experienced institutional violence in the form of creative destruction.

Responsibility and Lack of Childcare

Some of the girls experienced periods in their lives when they had no or minimal adult support. These multiply-marginalized dis/abled girls had to be responsible to raise not only themselves, but also many had to take care of siblings and/or even parents and act like “grown” adults (Jones, 2009). Erykah, a 17-year-old Latina who scowled nonstop and whose sharp tongue eviscerated many, discussed this absence of support as we sat in a “quiet room” in the step-down facility. The quiet room was not much bigger than a single stall bathroom with only a desk in it so I sat outside the door as we talked. She said, “My mom wasn’t there, nobody was there.” Erykah described in detail how she managed her life outside of school on her own, eventually becoming a mother and raising her daughter with minimal support. Erykah sighed, “Sometimes I feel like I’m the only one standing there, fighting.” Erykah was being forced to play an adult role in her life outside of school, but inside she was being treated as a child—one that had no rights. She verbalized how survival had become a battle and that school was a battlefield where being grown was unwelcome. She described her several conflicts with people in public schools by simply saying, “Nobody tells me what to do. Nobody.” Erykah’s attitude, born out of the responsibility she faced outside of school, was unwanted in school. Yet Erykah knew the importance of her education, so she kept going despite the feeling that no one at school was acknowledging this social conflict she was managing daily.

Many of the girls discussed how an absence of childcare directly affected the ways they interacted with public school and how school responded to them. Ashley, a 17-year-old multiracial girl who identified as Black, shared how she often went late to school specifically because she had to help her siblings, particularly her brother with autism, get ready for school.

I was taking care of my family but then, I would tell my mom I was going to school. Cuz I had to put my sisters and brothers in school so then I would already be late and then they’d be tripping on me because I was late so I would just leave and go with my friends and we’d just go ditch.

What is significant is that Ashley associated the punitive response of the school agents as the reason she would skip school. Public schools have also found ways to criminalize truancy directly, such as Texas’ previous law which made truancy a crime where students got tickets and could be jailed if they did not pay.4 Indirectly, tickets could be issued for trespassing if students were found in the halls during class time, as was the practice of one of the schools where I previously worked.

Ashley sat on the teacher’s desk in her English classroom at MLK, a narrow room with twelve student desks (chairs with writing platforms attached) and looked out the window. She recalled how when she arrived late to public school after getting her siblings ready and helping them get to their own schools via public transportation, she would be reprimanded with lectures, detention, or even suspension. Ashley described this situation saying,

Yeah, I had this math teacher and I missed like 3 months straight and she’s like, if you’re going to come here, you need to start coming more often because I don’t appreciate you missing this much of class and then you just want to drop in. And then I never went back to her class anymore.

The teacher labeled Ashley as someone who just wanted to “drop in,” not a girl with the additional responsibility of taking care of her family. Ashley continued, “That’s why I ended up in trouble, they just withdraw me after so many days, they just withdraw me.” Not only did teachers actively discourage her from coming, but the school removed her from the rolls. Ashley’s story is emblematic of creative destruction from individual teachers and schools that removed opportunities to learn. The school response to Ashley’s truancy was to institute a pedagogy of pathologization, being hyper-labeled as someone who did not care about school, being hyper-surveilled when she did attend class for coming late, and being hyper-punished through suspensions and eventually disenrollment. This pedagogy of pathologization exacerbated Ashley’s problems instead of alleviating them. Therefore, Ashley was punished not only for ...