eBook - ePub

Pensions, Politics and the Elderly

Historic Social Movements and Their Lessons for Our Aging Society

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pensions, Politics and the Elderly

Historic Social Movements and Their Lessons for Our Aging Society

About this book

This is an historical exploration of the US pensioner movements of the late 1920s through to the early 1950s, and the insights they offer policy analysts and researchers on how the forthcoming retirement of the Baby-Boom generation could proceed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pensions, Politics and the Elderly by Daniel J. B. Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Will the Boomers Have Their Ham and Eggs?

People are not going to be able to think about retirement the way their grandparents did, which was that retirement is a right and somebody will pay them to retire.Dallas L. Salisbury, President, Employee Benefits Research Institute (Barocas 1997, 26)

Demographic forecasting is founded on (some) known facts about the future. That is, projected population trends are based largely on knowledge of those who are already born. These folks will simply age into older brackets with the march of time and die off at reasonably predictable rates. But, of course, demographic forecasting has its risks, particularly as we go out into the distant future. Future birth rates and immigration rates cannot be known with certainty.

For example, back in the mid-1930s, when Social Security was being considered and its potential costs projected, estimates were made of future population trends. According to the experts of that period, the total U.S. population would level out at 151 million by the 1990s (U.S. Congress, Senate 1935, 50). As it turned out, the actual population by the mid-1990s was over 260 million and rising. Sadly, the forecasters back in the 1930s knew nothing of the post-World War II baby boom to come (nor even that there would be a World War II!).1 And they could not foresee the jump in immigration that would subsequently develop. What they did know about was the low birth rate during the Great Depression and the restrictive immigration policies then being followed.

Still, forecasts about demographics are less tricky than forecasts about the implications of demographics for the larger political economy. Specifically, what will be the reaction to future population developments? Even if we had perfect knowledge of future population levels and distribution, we could not know with any precision what impacts on the political process those trends would produce. An older population would surely require more medical care and other support than a youthful one. But how the economy and public policy would react to those costly health requirements is uncertain.

The Past Is Prologue

Despite these unknowns, this book suggests a scenario for the aging baby boom in the United States. It relies on past experience, namely developments centered in California in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. In that time and place the politics of the elderly had a major impact on the local and national scene. In particular, California was the home of the “Ham and Eggs” movement, a plan to pay citizens fifty years old and over “$30 Every Thursday” in a new California currency. And it was home of other elderly-based pension movements as well.

In the next two chapters, I describe the Ham and Eggs movement and how it developed. I will show that the Ham and Eggs plan was a natural outgrowth of the elderly demographics of California. The creation of Ham and Eggs—and the related movements described in Chapters 4 and 5—reflected the economic frustration of the elderly along with various currents of popular economic thought prevalent at the time. And I will argue that the retirement of the baby boomers will produce a twenty-first century counterpart to Ham and Eggs—that is, a political movement (or movements) coined from the thinking of that future era and earlier developments.

To be absolutely clear, I will not argue that someone in, say, 2030 will come up with a novel pension plan for folks over fifty to be financed by a newly created currency. We cannot know exactly what economic conditions will prevail at the time the boomers retire, nor can we know the path that popular and professional economic thinking will take between now and then. Inevitably, much speculation will be involved in the scenario I will be presenting.

But the story of Ham and Eggs and the other movements in California should serve as cautionary tales from the past. Those now discussing and making policy about Social Security and Medicare need to go beyond actuarial estimates. They need to consider political history and what it implies. There is an implicit assumption in policy circles that the baby-boom problem will be solved in the next few years through an interaction of reasoned reform options and the political process. Experts will research and discuss the issue, produce a consensus, and condition the political outcome by presenting feasible options. Politicians will then choose among the options. Once in place, the “solution” thus achieved will satisfy the aging boomers and the younger generations that must support their elders. History suggests it will not be so simple.

The Aging of the Baby Boomers

Everyone knows that the baby boom, which developed immediately after World War II, is pushing its way toward retirement in the twenty-first century, starting about the year 2010. As we go further and further out in the future, there are uncertainties concerning the exact proportion of the population that will fall into various age groups, as noted above. Trends in immigration, natural increase, rates of death, and factors yet unknown will determine the exact percentages. And the previously cited Social Security population projections of the 1930s should make us humble about very long-term forecasts.

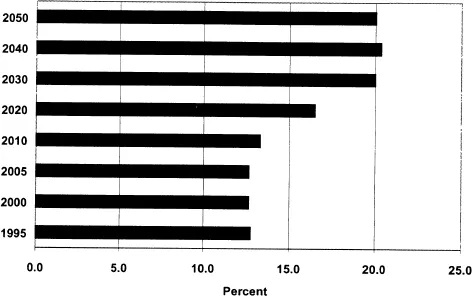

Still, that there will be a growing elderly population after 2010 is not a controversial proposition. As Figure 1.1 illustrates, the best guess is that the United States will become what one observer termed “a nation of Floridas.” That is, the proportion of the elderly in the future is expected to rise to levels similar to that of today’s state of preference for retirees (Peterson 1996).

Already the foreshocks of this bulge in the elderly population can be seen. Discussion in Congress on success in balancing the federal budget focuses on target years before baby boomers will retire. The reason is obvious: the Social Security and Medicare portions of the budget, no matter how well pre-funded they might be, must go into deficit as the boomers reach eligibility age.2 Even a fully funded system, however that phrase is defined, must save (run a surplus) before the boomers retire and then dissave (run a deficit) once they do.

In any event, Social Security and Medicare both are targeted for various degrees of fiscal overhaul; this is because the boomers’ retirement is not fully funded. Remedies proposed for this underfunding range from increases in payroll taxes and reductions in benefits to more exotic forms of “privatization” (Aaron 1997; Kotlikoff and Sachs 1997). Schemes are proposed to invest the trust funds or some new individual accounts in the stock market where they will (it is hoped) earn a higher return or to “reform” the Consumer Price Index (CPI) so as to reduce cost-of-living adjustments. But the end result of all these plans is that there is likely to be a reduction in benefits below what is currently promised to the boomers. In addition, younger generations will have to pay more into the systems or support their elders in some other fashion. These implications—which are likely to hold whatever Congress and the president decide—will be discussed more fully in the final chapter.

Figure 1.1 Percentage of the U.S. Population Aged Sixty-Five and Over: Middle Projection

Source: Estimates from the U.S. Bureau of the Census.

What will be the social and political reaction to these changes in the existing social contract? It is to that question that California history provides tantalizing insights.

Who Will Provide the Resources?

Politicians often focus on the Social Security and Medicare systems as if they were private benefit plans. They worry about inflows to, and outflows from, the federal trust funds just as the trustees for some private plan would do. In contrast, economists tend to concentrate on the issues the systems pose for national saving (Aaron 1982, 40–52). It has never been clear whether Social Security in fact substitutes for private retirement saving or whether the system is an add-on. That is, if Social Security or Medicare benefits were reduced, would individuals then save more for their retirements? And if they did save more, would they save enough completely to offset each dollar of reduction in Social Security and Medicare liabilities with an equivalent amount of private saving? The issue has long been debated. However, it is likely that improving the funding of the system—or adding some type of compulsory supplemental retirement saving plan to it—would add to net national saving.

Yet there has been political reluctance to improve system funding by an explicit payroll tax increase. When federal budget surpluses began to be projected, those who wanted to do least to Social Security and Medicare proposed “diverting” the surplus to these programs. In effect, such diversion adds to government saving. Overall, however, combined national saving from all sources (government, business, private households) has fallen short of investment in the United States for many years. This shortfall phenomenon, in turn, shows up as increased net U.S. international borrowing.

During the 1980s, the United States became the world’s largest international debtor. The taxpayer revolt of that era led to considerable expansion of the federal deficit—that is, to increased negative government saving (dissaving). Retiring the boomers in the twenty-first century can only reduce net saving in the United States, producing a propensity to continue running up net debt to the rest of the world. Institutionalized saving through Social Security—as noted earlier—will have to turn negative. There will also be increased drains on private pension plans. And the boomers will want to draw down the personal savings assets they control directly. Someone will have to buy the previously accumulated assets released from the public, private, and personal systems of saving.

In the popular literature the problem posed by this asset sale has been termed “the Big Chill” for financial markets. Questions are raised about who will buy the real estate liquidated by the boomers, not to mention their stocks and bonds (Sterling and Waite 1998). One thing is clear: The ability to borrow in world markets to finance the asset sell-off will be limited. Other developed countries have demographic bulges similar to America’s baby boom. Only Ireland—with a unique demographic profile—is an exception. Indeed, many nations, including (notably) Japan, face a much bigger jump in public pension spending on the elderly than does the United States, as can be seen in Figure 1.2 (OECD 1996). It is unlikely that ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Chapter 1. Will the Boomers Have Their Ham and Eggs?

- Chapter 2. Ham and Eggs

- Chapter 3. The Nonpension Ingredients of Ham and Eggs

- Chapter 4. Townsend Versus Social Security

- Chapter 5. Gerontocracy’s Last Stand: Earl Warren and Uncle George

- Chapter 6. Twenty-First Century Ham and Eggs?

- Notes

- References

- Index

- About the Author