- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

What is an Animal?

About this book

This book offers a unique interdisciplinary challenge to assumptions about animals and animality deeply embedded in our own ways of thought, and at the same time exposes highly sensitive and largely unexplored aspects of the understanding of our common humanity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What is an Animal? by Tim Ingold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

All human societies, past and present, have coexisted with populations of animals of one or many species. Throughout history, people have variously killed and eaten animals, or on rarer occasions been killed and eaten by them; incorporated animals into their social groups, whether as domestic familiars or captive slaves; and drawn upon their observations of animal morphology and behaviour in the construction of their own designs for living. People’s ideas about animals, and attitudes towards them, are correspondingly every bit as variable as their ways of relating to one another, in both cases reflecting that astonishing diversity of cultural tradition that is widely thought to be the hallmark of humanity. Yet, in the recognition of this diversity, we are immediately presented with an awkward paradox. How can we reach a comparative understanding of human cultural attitudes towards animals if the very conception of what an animal might be, and by implication of what it means to be human, is itself culturally relative? Does not the anthropological project of cross-cultural comparison rest upon an implicit assumption of human uniqueness vis-à-vis other animals that is fundamentally anthropocentric? Moreover if we follow the promptings of modern evolutionary theory in recognizing the essential continuity between human and non-human animals, does this not entail the adoption of an ethnocentrically ‘Western’ conception of human nature? Is it possible, even in theory, simultaneously to transcend the limitations of both anthropocentrism and ethnocentrism?

With dilemmas such as these in mind, the programme for the major theme of the World Archaeological Congress on ‘Cultural Attitudes to Animals’ was prefaced by a session in which contributors were invited to address the key question ‘What is an animal?’. Each contributor was asked to tackle the question from his or her personal or disciplinary point of view, and I made a deliberate attempt to include perspectives from as wide a range of disciplines as possible, including social and cultural anthropology, archaeology, biology, psychology, philosophy and semiotics. It came as no surprise that my question spawned answers of very different kinds, and that they disagreed on many fundamental points of principle. Perhaps more surprising was the degree of passion aroused in the course of the discussion, which seemed to confirm two points on which I think all the contributors would agree: first, that there is a strong emotional undercurrent to our ideas about animality; and, secondly, that to subject these ideas to critical scrutiny is to expose highly sensitive and largely unexplored aspects of the understanding of our own humanity.

The limits of the animate

Of course, the question ‘What is an animal?’ can itself be construed in any number of ways, all of which are concerned with problems surrounding the definition of boundaries, whether between humans and non-human animals, animals and plants, or living and non-living. The last of these boundaries is the most inclusive, for it rests upon the criterion of animacy, on the very distinction between animate and inanimate objects. This is a central theme in two of the contributions to this volume: those by Reed and Goodwin. Reed argues that the distinctive property of animate beings lies in their capacity for autonomous movement – that is, movement is what animals do, rather than the mechanical resultant of what is done to them. This leads him to ask what one animal can afford to another in its environment that an inanimate object cannot. He shows that, besides being autonomous agents which can ‘act back’ or literally interact, all animate objects have the property of undergoing growth and that, unlike machines, their activity is never perfectly repetitive. For Goodwin these dynamic properties of organisms represent the starting point from which he attempts to resolve the problem of the generation of form in biology, a problem that until now has proved resistant to approaches couched in terms of a conventional, reductionist paradigm inspired by the Cartesian view of the animal as a complex automaton. Adopting a logic of process, he shows that the stability of form is not given by the interaction of its elementary constituents, but is actively ‘held in place’ by a movement of intention: thus, change is primitive, persistence is derived. In Goodwin’s words ‘it is not composition that determines organismic form ad transformation, but dynamic organization’. From this he concludes that the animal is not an automaton but ‘a centre of immanent, self-generating or creative power’, one locus in the continuous unfolding or modulation of a total field of relations. But to take this philosophy of process to its ultimate conclusion is to dissolve the very boundaries of the animate, to recognize that in a certain sense the entire world is an organism, and its unfolding an organic process.

Rather less inclusively, the question ‘What is an animal?’ is one of macrotaxonomy – of distinguishing animals from the other major classes of life forms such as plants, fungi and bacteria. This is one sense in which the question is taken up by Sebeok. He begins with a characterization of the fundamental properties of living systems, which link two processes: one of energy conversion, the other an exchange of information. All organisms receive signs from their environments, transmuting them into outputs consisting of further signs, but this sign-process – or semiosis – may be radically different for animals from what it is (say) for plants. The varieties of semiosis, raising fascinating questions (to which I shall return) concerning the ways in which organisms of different kinds engage in the construction of their own environments, provide one basis for their possible taxonomic distinction. Sebeok reviews semiotic and other ‘scientific’ macrotaxonomic criteria by which animals may be distinguished from other forms. There are, of course, many alternative criteria, and hence there can be multiple taxonomies, whose number is immeasurably increased if we accord equivalent value (and validity, on their own terms) to the ‘folk’ taxonomies of other cultures, based as they often are on a profound practical and theoretical knowledge of the natural world. Just as a deeper understanding of a myth, following the advice of Lévi-Strauss (1985), may be obtained from the simultaneous reading of its many versions, so perhaps we can come closer to discovering the meaning of the ‘animal’ by treating each taxonomy as one of a set, each providing a partial answer to a problem whose complete solution requires a reading of the entire set as a structured totality.

Animality and humanity

Although our question touches on the properties of both life and the major classes of organisms, it is more popularly construed, narrowly and reflexively, as a question about ourselves. Every attribute that it is claimed we uniquely have, the animal is consequently supposed to lack; thus, the generic concept of ‘animal’ is negatively constituted by the sum of these deficiencies. But as Clark observes in his contribution to this book, whatever attributes might popularly be selected as the distinguishing marks of humanity (and these vary from one culture to another), we shall find some creatures born of man and woman who – for whatever reason – fail to qualify (see also Hull 1984, p. 35). One controversial attribute, which I discuss later but which will serve for now as an example, is the faculty of language. There are some individuals of human descent who lack this faculty. To date, no animal of any other species has conclusively been shown to possess it, though many claims to this effect have been made. But this does not mean that one may never be found, nor does it rule out the possibility that a linguistic capacity fully equal to our own might, in future times, evolve quite independently in some other line of descent, without its bearers thereby joining the human species.

Supposing that humanity were defined as Homo loquens, a natural kind including all animals with language and speech, we would have to admit the possibility both of individuals of human parentage ‘dropping out’ of humankind, and of individuals of non-human parentage ‘coming in’. But if by humanity we mean the biological species Homo sapiens, the former would unequivocally belong and the latter would not. Comparing ‘folk’ and ‘scientific’ taxonomies, Clark shows that biological species (our own included) are not natural kinds. That is, the individuals of a species are linked by their genealogical connection, as actual codescendants of a common ancestor or as potential co-ancestors of a common descendant. Given the variability and unpredictability of the similarities and differences between individual human beings and organisms of other species, it follows that if the boundaries of the moral community are defined sufficiently widely to embrace all human beings and their future descendants, then by the same token they must embrace the non-human animals with which humans share a common ancestry. This at once calls into question even the best-intentioned attempts to validate our moral and political ideals by appeal to a common, species-specific humanity, and has considerable implications with regard to our responsibilities towards non-human animals. For it inevitably blurs those comfortable distinctions by which we order our lives: between domestication and slavery, hunting and homicide, and carnivory and cannibalism.

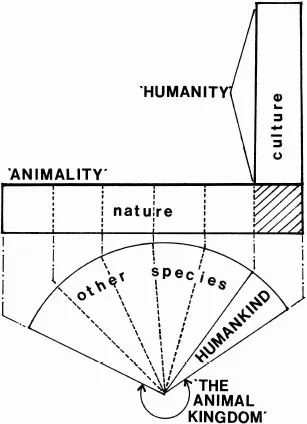

As Midgley points out, in her discussion of the history of the terms ‘animal’ and ‘beast’, the former term is now commonly employed in two contradictory senses: one benign and inclusive of humanity, the other negative and exclusive, denoting all that is considered inhuman or anti-human. Tapper remarks on the same phenomenon, noting how this ambivalence in the conception of animals, as both akin to us yet alien in their ways, makes them peculiarly apposite as models or exemplars in the process of socialization, or the intergenerational transmission of culture and morality. Coy also observes the inconsistency, in recent Western literature on animal welfare, between treating animals as ‘dumb beasts’ that are worthy of protection, and attributing to them the full gamut of human feelings. These contradictions stem, to a large degree, from our propensity to switch back and forth between two quite different approaches to the definition of animality: as a domain or ‘kingdom’, including humans; and as a state or condition, opposed to humanity (see Fig. 1.1). In the context of the first approach, humankind is identified with the biological taxon Homo sapiens, one of an immense number of animal species inhabiting the Earth, connected synchronically in a complex web of ecological interdependencies, and diachronically in the all-encompassing genealogy of phylogenetic evolution. Quite clearly the process of ‘becoming human’, which Tanner charts in her chapter, although it entailed a unique sequence of morphological and behavioural innovations, was not a movement out of animality but an extension of its frontiers. In this sense, modern humans are no less ‘animal’ than Australopithecines or chimpanzees.

Figure 1.1 Two views of animality: as a domain (including humankind) and as a condition (excluding humanity). The shaded area represents human nature, or ‘human animality’.

Yet, following the second approach, the concept of animality has been employed to characterize a state of being otherwise known as ‘natural’, in which actions are impelled by innate emotional drives that are undisciplined by reason or responsibility. In this guise it has been extended to describe the imagined condition of human beings ‘in the raw’, untouched by the values and mores of culture or civilization. ‘Becoming human’, then, is tantamount to the process of enculturation which virtually all children of our species undergo in their passage to maturity and which – according to an earlier anthropology – the entire species is destined to undergo in its uneven passage towards civilization. This view of emergent humanity – as an overcoming of, rather than an extension of, intrinsic animality – lay behind the attempts of many 19th-century anthropologists to reconstruct ‘human nature’ as a universal baseline for all subsequent social and cultural evolution. It continues to inform much of the more popular sociobiological speculation on the same theme, which usually takes the form of a search for the prototypes of human behavioural responses in the innate repertoire of other species. The approach is exemplified in this book by Mundkur, though in substance his contribution is in a different class altogether, since it is backed by a formidable, discipline-spanning erudition and a colossal weight of empirical documentation of the kind that most human sociobiology so conspicuously lacks.

Mundkur is concerned to uncover the primordial foundations of what he calls ‘religiosity’, defined as ‘a state of mind incited by belief in forces perceived as supernatural’. This state of mind, he argues, is embedded in the emotion of fear which is demonstrably wired-in to the sensory systems of at least all higher vertebrates, and which has clear adaptive functions that would have promoted its establishment under pressures of natural selection. What appears, in the history of religions, as an almost capricious diversity of belief and practice, is in fact this base religiosity refracted in countless ways through the cultural traditions that have been superimposed upon it. It is rather significant that Mundkur presents his project as an enquiry into ‘human animality’, an enquiry that calls for mechanistic explanations couched in terms of the ‘harder’ biological sciences – genetics, biochemistry and neurophysiology. Of course, this kind of enquiry is anathema to many social and cultural anthropologists for whom, as Tapper notes, ‘human nature is cultural diversity’. From their perspective the essence of humanity is constituted, in opposition to animality, by a ‘capacity for culture’ whose historical and contemporary manifestations make up the subject of study for the range of disciplines collectively known as the ‘humanities’. Paradoxically, the sociobiological quest for the rudiments of human nature turns out to be an attempt to discover what is inhuman in man – to characterize the human being stripped of humanity, revealing an animal residue.

Thus, although as members of a particular species human beings unquestionably belong to the animal kingdom, they are also seen to embody two contrary conditions, to which Western thought has attached the labels of animality and humanity (Fig. 1.1). Of these the latter points to the status of the particular human being as a person, an agent endowed with intentions and purposes, motivated in his or her actions by social values and a moral conscience. The conceptual ambiguity is no accident; it reflects a widely held belief that (with the exception of quasi-human animals such as pets) personhood as a state of being is open only to individuals of the species Homo sapiens, both the moral condition and the biological taxon being conflated under the single rubric of ‘humanity’. According to this belief, whereas humans can behave in a way that is considered ‘inhuman’ or ‘bestial’ if they allow themselves to be unduly swayed by primordial passions (particularly the nastier ones), animals of other species can only act ‘as if continually in a passion’, and therefore – like human infants – they are in no way responsible or accountable for what they do (Shotter 1984, p. 42). It follows that although we may, following Mundkur’s example, launch an enquiry into human animality, there can be no enquiry into the humanity of non-human animals. That is, acts which, if performed by humans, we would have no hesitation in regarding as intentionally motivated and culturally designed would, if performed by animals, have to be explained as the automatic output of an innate, genetically determined neural mechanism.

Intentionality and language

Midgley has trenchantly exposed the double standards inherent in this view. Why, she asks, should intentionality be excluded from the scientific conception of the animal, even though it seems self-evident to practical people who have actually worked with such animals as dogs, elephants or chimpanzees that their actions have an intentional component, just as the intentionality of our own actions is self-evident to us? Her answer is that the science of animal behaviour has been deluded by a kind of ‘species solipsism’, a sceptical pretence of ignorance about the content of animals’ conscious states. In their attempts to account for the often very complex and variable performances of other species, in a way that does not transgress the conventional bounds of animality, scientists have been forced either to simplify their descriptions of what the animals do by omitting troublesome detail, or to propose the most tortuous and convoluted mechanisms for generating the observed patterns. Yet the normal, scientifically approved principle of explanatory parsimony, if consistently applied, would favour much more economical accounts couched in terms of the animal’s abilities to make their own adjustments of means to ends through a process of rational deliberation.

The view that non-human animals may be regarded as self-conscious subjects with thoughts and feelings of their own is still something of a heresy in ethological and psychological circles. It has been vigorously championed in recent years by Griffin (1984), of whose work Midgley is a strong advocate. Griffin’s ideas on the question of animal awareness are also discussed in this book by Coy and by Ingold. Coy admits some scepticism, but is prepared to accept the notion that non-human animals engage in conscious thinking at least as a working hypothesis, and in order to redress the heavy Cartesian bias in favour of the view that they do not. There is, after all, no a priori reason why the latter should be accorded more credibility than the former. Moreover, the kinds of selective pressures that might have promoted the development of conscious awareness in humans should have been equally at work on other species with which humans have had close and lasting contacts. Coy suggests that these pressures would have lain in the adaptive advantages for the individual of one species conferred by the ability to predict the likely actions of individuals of the same or another species – whether predators, competitors or prey. Thus, to the extent that the human hunter benefits from forecasting the reactions of the deer, so the deer benefits from being able to predict the hunter’s prediction, and to confound it by exercising autonomous powers of intentional action. So every increment in the development of awareness on one side of the interspecific relationship would increase the pressure for further development on the other, and vice versa.

Where Midgley is an advocate and Coy a sceptic, Ingold is strongly critical of Griffin’s arguments. His criticisms hinge on the controversial issue of whether non-human animals are endowed with the faculty of language, an issue that is also touched upon briefly by Tanner. Her point is that the claim ‘humans alone have language’ can only be sustained by arbitrarily selecting, as definitive of language, those design features apparently peculiar to human communication: the employment of words and syntax. Yet, in common with other animals, humans communicate by means of an extensive repertoire of non-verbal signs. By what right do we privilege verbal communication among human beings over non-verbal communication among other animals? If it were true that language is no more than a species-specific mechanism of communication, in that sense comparable with other, equally distinctive mechanisms employed by other species, then there would be some force in this objection. However, there are strong arguments against the common presumption that the primary function of language is one of communication. These counterargum...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Is humanity a natural kind?

- 3 Beasts, brutes and monsters

- 4 Animality, humanity, morality, society

- 5 ‘Animal’ in biological and semiotic perspective

- 6 Animals’ attitudes to people

- 7 The animal in the study of humanity

- 8 Organisms and minds: the dialectics of the animal-human interface in biology

- 9 The affordances of the animate environment: social science from the ecological point of view

- 10 Becoming human, our links with our past

- 11 Human animality, the mental imagery of fear, and religiosity

- Index