- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

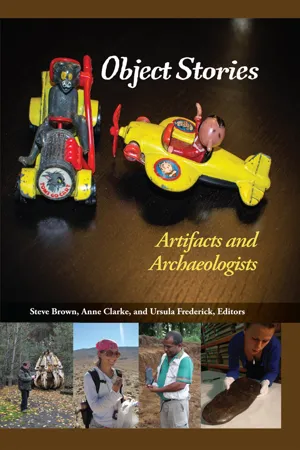

About this book

Archaeologists are synonymous with artifacts. With artifacts we construct stories concerning past lives and livelihoods, yet we rarely write of deeply personal encounters or of the way the lives of objects and our lives become enmeshed. In this volume, 23 archaeologists each tell an intimate story of their experience and entanglement with an evocative artifact. Artifacts range from a New Britain obsidian tool to an abandoned Viking toy boat, the marble finger of a classical Greek statue and ordinary pottery fragments from Roman England and Polynesia. Other tales cover contemporary objects, including a toothpick, bell, door, and the blueprint for a 1970s motorcar. These creative stories are self-consciously personal; they derive from real world encounter viewed through the peculiarities and material intimacy of archaeological practice. This text can be used in undergraduate and graduate courses focused on archaeological interpretation and theory, as well as on material culture and story-telling.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

ENCOUNTER, ENGAGEMENT, AND OBJECT STORIES

Figure 1.1 Shadow board #3. (Image credit: U. K. Frederick, 2013)

WHAT THIS ALL MEANS

I turned my attention to a small awl handle, delicately inscribed with a series of dots and lines. I felt certain that a Wahpeton woman had once used that tool at Little Rapids and that its inscriptions conveyed a great deal about her accomplishments to those who understood their meaning.

These words are drawn from Janet Spector’s 1993 seminal publication, What This Awl Means: Feminist Archaeology at a Wahpeto Dakota Village. Spector’s book, described at the time of publication as ‘revolutionary’,1 was motivated by a desire to inject humanity into the way she wrote about the past. Central to Spector’s project was a quest to personalise the past, to find and express empathy and feelings for people and objects revealed via archaeological investigation, and, most of all, to resist representing the past through detached, distanced, and objective forms of writing.2 No greater compliment could be made to the book, in our view, than the words of Carolynn Schommer: ‘The young Dakota woman whom Janet Spector writes about was our grandmother. Having worked with Janet on the Little River project, I respect her sensitivity: for us to be involved, as Wahpeto people, was really special.’3

How many archaeologists can truly say that a narrative of their work elicited from a community member, volunteer student, land owner, or government official such a heartfelt and generous response? That is, an empathic response to the archaeologist’s place-story rather than a ‘thanks’ for being ‘allowed’ to participate in field practice. We, the editors, recognise that personal interactions of field participants and in situ accounts and imaginings of field experience are seldom visible in final archaeological field reports or published accounts. The archaeologist often views situated experiences of archaeological work as frivolous and, therefore, ‘other’ to orthodoxies of expertise and authority. There is often a disjuncture between what occurred during field and laboratory work, such as speculation concerning object meanings, and what is officially reported. We refer to these unreported personalised experiences, anecdotes, and imaginings as ‘hidden histories of archaeological practice’. These stories are not ‘hidden’ because they speak of objects that have yet to be found nor because they are mundane objects overlooked in a discourse of spectacular discovery. They are hidden simply because they are stories that often remain untold.

CASTING SHADOWS

We open this chapter with the image of a shadow board to illustrate the volume’s primary concern with making the hidden stories of archaeological practice visible. In pragmatic terms the shadow board is a device for organising and storing tools. As a visual aid it allows the viewer/maker/technician to quickly discern the location of a particular implement as well as determine which tools are present and which, if any, may be missing. In this respect the shadow board also represents a kind of classification system, whereby each tool is categorised and assigned a position that is marked out with an outline or silhouette shape indicating where each tool ‘belongs’—pliers hang alongside scissors, hammers reside near screwdrivers, spanners of all sizes fit together, and so on. In the shadow board of this introduction it is evident that all of the objects are missing. That is, all that is left of these objects, all that we now see are ‘shadows’—the representation of objects’ ‘having been’.

From philosophy and physics through to psychoanalysis and art history, the shadow is freighted with a convoluted symbolism and currency.4 Perhaps in the simplest rendering the shadow speaks to complex questions of perception and representation. It defines form but obscures detail. In the shadow the absence of the object is coupled with the presence of the object’s projection. So while the shadow of the object may signal a sort of emptiness—the object is gone—this emptiness is also a powerful imaginative force because it invites us to imagine—to fill in the gaps, as it were. For this reason the shadow board is, we feel, an especially apt visual metaphor for the stories told in this collection. We know from our own experiences and through our conversations with colleagues that rich object stories exist, but only the outline of their presence may be discerned in the discourse that dominates the discipline.

Moreover, the shadow board alludes to conventions of representation—a virtual template—by which we allow our disciplinary voice to be constructed, conveyed, and heard. So what are the kinds of stories that lie in the shadows of archaeological knowledge, and what is the shape of things to come?

This volume makes visible stories and feelings of intimacy otherwise masked behind veils of authority. Central to this project are ways of writing about the present/past, telling stories, and the public presentation of archaeological accounts. The narratives hark back to the work of Janet Spector and beyond that, to James Clifford’s and George Marcus’ 1986 edited volume Writing Culture. The latter book is well known for sparking a ‘crisis in representation’ in American cultural anthropology and caused anthropologists to scrutinise their texts and develop new ways of working reflexively: ‘In essence, the collective message of the book’s authors was focused on the authority of the ethnographic text. They questioned the established modes of ethnographic writing that embodied a single authorial voice and thereby, it was argued, a privileged ethnographic gaze. The consequence was—in some quarters—a radical reappraisal of how ethnographies are written.’5

We argue for a radical reappraisal of how archaeologies are written. This is not to suggest all current archaeological interpretive work is detached, distanced, and objective or that such accounts are necessarily problematic. Far from it. In our view, however, self-styled scientific, rationalist approaches remain dominant in the field. This volume is a call to archaeologists to better assimilate and integrate objective and subjective, popular and academic, first person and third person forms of writing. To recall our earlier metaphor, we are inviting our colleagues to reunite the trowel with its shadow and, in effect, reconfigure the dynamics of archaeology’s re-presentation. Whilst we might look within the discipline, to Janet Spector for example, for inspiring ways of rewriting, we would also point to work in other scholarly fields (e.g., material culture studies, science and technology studies, anthropology, sociology, history, heritage studies) and other genres such as autobiography (including works by archaeologists)6 and fiction.7 This book is a contribution to textual forms emphasising closeness between archaeologist and artefact.

The twenty-four chapter authors presented in the volume reveal and relate personal perspectives concerning archaeological practice. Objects or artefacts act as focal points. The stories tell of excitement and fallibility, object-ive analysis and informed imagination, frivolous yet serious, and ways in which archaeologist and artefact become entangled. Our motivations for compiling the assembled stories are twofold. First, we present a collection of diverse stories and narrative forms that can assist and inspire archaeologists as well as scholars who work with material culture to craft new ways of writing creatively on finds and feelings. We do not argue for personal and engaging accounts of archaeological work as ‘other’ to rational, scientific approaches but rather call for complementary and intertwined forms of blended storytelling. Second, the stories contribute to work being undertaken more broadly in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences concerned with material things. This volume, therefore, makes available to wider nonarchaeologist audiences particular archaeological perspectives and ways of constructing knowledge. The final chapter, an afterword written by Jane Lydon, contextualises the object stories in relation to a broad social sciences and humanities literature.

In this introduction we consider how archaeologists experience things, objects, and artefacts and how hidden histories of field practice are revealed and related.8 We draw primarily on the object stories presented in this book (our ‘data’) to discuss how archaeologists encounter, nurture, and write about artefacts with which they become personally connected. To this end our discussion is framed under three sequential topics: discovering affective objects, cultivating objects, and object stories.

DISCOVERING AFFECTIVE OBJECTS

Sociologist/psychologist Sherry Turkle, a scholar who writes on the ‘subjective side’ of people’s relationships with technology, has edited books on things and thinking. In the introduction to an edited volume of autobiographical essays, Evocative Objects: Things We Think With, Turkle tells of her childhood fascination with a ‘memory closet’ of family keepsakes. In each keepsake (a photograph, address book, business card) her childhood self sought clues for locating her father, who had been absent and never spoken of since she was two: ‘I was looking, without awareness, for the one who was missing. I was looking for a trace of my father.’9 Turkle’s search might be read as archaeological in nature because it starts with a discovery and then uses found objects to seek answers and formulate new questions.

In Turkle’s childhood quest the dual meanings of ‘discovery’ are evident—that is, discovery as initial encounter with an object or collection and discovery as learning something for the first time. In a simplistic sense one might associate initial encounter with the immediacy of affect and emotion and new learning with a longer-term application of intellect. For the purpose of examining the object stories presented in this volume, we begin by considering the former meaning of discovery: discovering affective objects.

Archaeology is a discipline that studies the past through material remains. Historically the field has been told through great discoveries and metanarratives, but it is also concerned with small things and not-so-ordinary lives. In this volume we are not concerned with the stories of iconic sites, such as Hiram Bingham’s discovery of Machu Picchu in 1911, Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter in 1922, or hominin footprints at Laetoli by Mary Leakey in 1978. Rather, the stories focus on ordinary objects, such as pot sherds, toothpicks, a fragment of statue, and an abandoned industrial machine. How were these objects discovered? What happened in the moment of author-archaeologist and artefact contact?

For archaeologists, encountering artefacts takes place in many contexts. Typically archaeologists find artefacts whilst undertaking excavations or field survey or whilst examining institutional collections. This is the case for many of the objects discussed in this book. Some were recovered via excavation—grass remnants of a Neolithic basket from Turkey, a stone-lined fireplace in a Neolithic house in Korea, a Viking toy boat from Dublin, a marble finger detached from a classical Greek statue, a sherd of Polynesian pottery from Samoa, and a group of Roman ceramic fragments from England. The obsidian stemmed artefact from New Britain, Papua New Guinea, was also found during excavation but in this instance was salvaged when a bulldozer exposed it. Some artefacts were encountered during field survey, such as the Acheulian hand axe in Jordan, an abandoned machinery ‘claw’ at Chernobyl, a vernacular door at a Ugandan refugee camp, and a rock engraving of a man with a hat and pipe in Australia. A further group of artefacts were encountered in institutional collections—a Bronze Age axe at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge; ivory toothpicks in the Ivoryton Library, Connecticut, United States; a cake of spinifex resin at the South Australian Museum; a wood and iron–nail club at the Hurstville Museum, Australia; and prints of the iconic Australian Sandman panel van stored in the South Australian archives. For Heather Law Pezzarossi, the collection that is the origin of her story is her own flea market–acquired assemblage of tintypes.

Some artefacts discussed in this volume arise from other forms of encounter. A number of the object stories concern gifts. Emma Waterton tells of a copper vessel given ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1. Encounter, Engagement, and Object Stories

- 2. What This Awl Means

- 3. On Toothpicks and Elephants

- 4. Walking Straight Through Places and Times: Finding an Acheulian Hand Axe

- 5. Marooned! The Old People, a Dolphin, and a Model Canoe

- 6. Shalimar

- 7. Karma’s Father’s Cup

- 8. Tradition and Inventiveness: Decolonising an ‘Indian’ Bell

- 9. A Voyage of Discovery: Biography and Identity in Early Medieval Dublin and Today

- 10. A Steely Gaze: My Captivation with the American Tintype

- 11. A Cake of Spinifex Resin

- 12. Can, Door, Heritage

- 13. Pointing to the Past

- 14. The Reality of Whales: Reflections from a Follower of Whales

- 15. The Salt Pan Creek Boondi

- 16. Transformative Material, Transformative Object: The Impact of a Bronze Axe

- 17. The Prosaic Platter

- 18. The Claw: A Song of Electrons

- 19. Reflections and Connections

- 20. Dido and the Basket: Fragments Towards a Nonlinear History

- 21. A Neolithic House with Two Hearths at Osanni, South Korea

- 22. Naughtiness on the Mission

- 23. The Materiality of Plainware Pottery in Polynesia

- 24. Man with Hat and Pipe

- 25. Enter Sandman

- 26. Naming Our Love

- References

- Index

- About the Authors and Contributors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Object Stories by Steve Brown,Anne Clarke,Ursula Frederick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.