- 245 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is an inquiry into the relationships between archaeology, colonialism and ecotourism at the famous standing stones of Hintang, Laos. It investigates the conditions under which archaeological knowledge has been produced, appropriated, contested, commodified, and consumed by colonialism from the 1930s until today and what it shows about the power dynamics of heritage and ecotourism. The volume-explores how the discourses of colonialism and ecotourism affect tourists, archaeologists, heritage managers, and the local community;-is written as a set of overlapping creative essays, each giving an overlapping perspective on Hintang;-is a multidisciplinary research project based on ethnographic fieldwork, archival research, interviews with community members, biography, material culture studies, and text analysis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stones Standing by Anna Källén in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

In the beginning, there were only stones: silent and alluring, standing tall among the mountaintops, with nothing worthy of comparison in sight. Bunches of stone planks lined ancient pathways like beads on a string along a 12-kilometre mountain ridge. But soon I saw tilting and lying stones too. Then I noticed the magnificent stone discs on the ground. Large and amazingly thin, they had been skilfully crafted from micaceous schist. Beside some of the discs were deep holes in the ground. Looking carefully I saw that some had steps hollowed out or inserted into the walls. These were entrances to ancient underground chambers, once covered by the large discs. Trees and bushes, grazing cattle, bombs and bullets, new road construction, villagers and visitors have touched, moved, and recontexualised them into the frozen moment when I first came to meet them.

You will find them in the northeastern corner of Laos, near Road 6 between the provincial capitals Phonsavan1 and Sam Neua.2 This corner of Laos, or more correctly the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), is called the Houaphanh province. Houaphanh means literally “a thousand heads”. The province is characterised by its breathtaking mountainous landscape and is famous for its production of high-quality textiles. It is also known as the birthplace of the Lao Communist movement Pathet Lao; as a consequence, the province was subject to severe bombardment during the Vietnam War. Houaphanh is today defined as one of the poorest of Laos’ 15 provinces, and Laos itself as one of the poorest countries in Asia.3

They are called Hin tang, which in Lao means “standing stones”. A total of 1,546 stones and 153 discs have been arranged in 72 groups, most of them in the saddles of one single mountain ridge, 1,500 metres above the sea. Silent they stand, in thin cool air among the mountaintops, as curious vestiges of bygone times against a background of brutal wars and scarce resources. They are surrounded by intriguing stories and are entangled in complex and often contradictory matrices of meaning. As such, they have an extraordinary potential to challenge what we think we know about the past and the present.

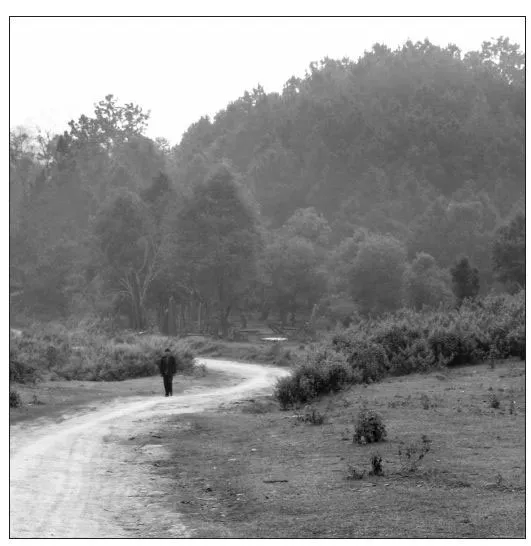

Figure 1.1 Hintang in November 2007. Photo: Anna Källén.

Between 1893 and 1954 Laos and Hintang4 were part of French Indochina. At the end of the nineteenth century, in the heyday of colonial expansionism, archaeology was born as an academic and scientific discipline in Europe. In this book I demonstrate how archaeology nourished and was nourished by colonial ideology, and gave scientific legitimacy to colonial notions of race and development. I maintain that Hintang became an archaeological site through the French modern mission to register and protect every important vestige of Indochina’s past. The landscape of chambers, discs, and stones was most certainly known and embedded in various meshes of meaning prior to the French intervention. But it was the French investigation in 1933 that sorted its components into the linear, layered, and essential order characteristic of an archaeological site. Madeleine Colani was the archaeologist in charge, representing the colonial research institute EFEO (l’École française d’Extrême-Orient). Colani worked for two months at Hintang, assisted by a representative from the native government,5 her sister Eléonore, and a number of unnamed local villagers. The results from their excavations and surveys were compiled in scientific drawings, maps, tables, and interpretations and published by Colani in an extensive two-volume report along with their investigations of the famous Plain of Jars in the nearby Xieng Khouang province.6 In the report, Colani concluded that the standing stones were old cemeteries, traces of a mysteriously vanished megalithic civilisation that had once flourished around ancient salt trade routes.

After the Colani sisters had left, Hintang entered decades of turbulence and war. Archaeology was not a top priority at times of war and revolution, and therefore Colani’s story would remain uncontested as the only written version of Hintang’s past until quite recently.7 It was not until the early 2000s that the standing stones once again attracted archaeological attention. The Lao historian Souneth Pothisane conducted an unreported survey there around the turn of the millennium, and a few years later archaeologist Viengkeo Souksavatdy from the Ministry of Information and Culture led another survey and restoration project in collaboration with the French archaeologist Catherine Raymond. The latter project came about as a result of a U.S.-funded road construction project in 2001. With no instructions regarding heritage sites, the construction team had cut through and demolished parts of the large stone site San Khong Phan and several smaller stone sites when constructing the road. Unaware of the new road, Raymond and her American husband came to see the stones and found them in the process of destruction. Upset by what they saw, they managed to convince the U.S. Embassy to contribute funding for a heritage conservation project.8 The project involved some surveys that only confirmed Colani’s earlier reports,9 but more importantly it laid the foundation for later tourism activities with the mapping and signage of a “Hintang Trail” and the transformation of San Khong Phan to a visitor’s centre and “Archaeological Park”. Most of the signage that directs tourists to Hintang, as well as a large Vietnamese-style hardwood picnic shelter at San Khong Phan, resulted from this project managed by Raymond and Souksavatdy.

In the time between Colani’s and Souksavatdy–Raymond’s archaeological projects, the world had changed dramatically for the people living near Hintang. The Houaphanh province had been deeply involved in war and conflict during the twentieth century. Lives and landscapes were reshaped by anticolonial uprisings, the Second World War, and later the intense fighting between the Royal Lao Army and Pathet Lao (the Lao communist party), a conflict known to the western world as the Vietnam War. This ended in 1975 with the establishment of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, which remains today as a one-party communist state. Because of its historical links with the early days of Pathet Lao, the Houaphanh province is now celebrated in nationalist contexts. It is marketed to international tourists as the birthplace of Pathet Lao, and support for the communist regime remains exceptionally strong here. Most of the people who live near Hintang today ascribe themselves to the Lao majority ethnic group, but there are also people who call themselves Hmong, Khmu, and Phong.10 Most of the senior members of these communities have had their lives shaped by the experience of war.

Since the late 1990s, the Lao communist regime has joined the tourism vogue among Southeast Asian countries. Tourism is among the largest and fastest growing industries in the world today, and a country as impecunious as Laos cannot afford to reject such income opportunities, even if mass tourism is not quite compatible with orthodox communist ideology. After having tried to control and regulate the tourism market, the Lao regime has in more recent years turned to ecotourism. Ecotourism focuses rhetorically on local culture and conservation, and it is often talked about in terms of responsible poverty alleviation.11 Compared with the average mass tourist, the ecotourist is supposed to be wealthier, more culturally aware, and more responsible. For the Lao regime, ecotourism has thus offered an opportunity to gain the profits promised by the tourism business, but avoid the trashy consequences of mass tourism.

Hintang was first mentioned on a list of possible sites for ecotourism promotion in 2005. The ecotourism industry is generally keen to be associated with archaeological sites, particularly sites that are portrayed as threatened and in need of safeguarding. Sites are even more attractive if they can be described as adventurous and authentic while at the same time being accessible, without too-costly sacrifices of general tourist comforts such as soft drink vendors and WCs. The lack of such on-site comforts, as well as its location—hours on meandering mountain roads from the nearest town with comfy-enough hotels for organised group travellers—are Hintang’s greatest disadvantages as an ecotourism site. But its weathered beauty and aura of archaeological adventure and authenticity have kept regional authorities hopeful for a future tourism boom. In the last decade, there have been projects to increase signage and road accessibility to the main Hintang site.12

I have worked with archaeology and heritage research in Laos for nearly 20 years, and for me, this book represents in some sense a break-up from Laos. I have always been an odd partner to Laos, with a body too large and a temper too hot. “Water on your chest”, my Lao colleagues used to say (not so rarely) when they thought I was too angry or upset for my own good. Like any partner in life, Laos has come to define parts of my identity. My relationship with Laos has brought me friendships and experiences without which I would not be who I am. But now it is time to break up. And the firm knowledge that this is the end of the road for Laos and me has somewhat surprisingly offered me a new, less anxious, position to think and write from.

The 10 essays of this book are based on fieldwork, archival research, and textual analysis done in my last research project in Laos, at Hintang from 2006 to 2009.13 But the questions and curiosities that eventually led to the writing of these essays began more than a decade earlier. In 1995 I became involved in archaeological investigations at the Lao Pako site near the capital city of Vientiane with my friend and colleague Anna Karlström.14 I was young and had strong ideas about archaeology’s great global potential to solve the enigmas of the origins of humanity and extract the essence of national identities. Over the years that I worked with excavations and surveys at Lao Pako, my previously self-secure and benevolent worldview was repeatedly shattered. Laos hit me in the face. It was not the homogenous smiling country I had imagined, full of primitive people waiting for my Swedish archaeological salvation. Instead, I experienced a beautiful country full of viciousness and prestige, of kindness, of brilliant intelligence and broken dreams. There somewhere I began to be concerned and eager to learn more about the role of archaeology in structures of power and unequal opportunities of the world today.15

As the Lao Pako project came to an end and the Hintang project was being formed (originally in 2004 as a wish expressed by my colleague Kanda Keosopha to study relations between heritage and ethnicity at Hintang), I had grown a more general interest in the impacts and consequences of archaeological knowledge production in the postcolonial world. In my work with Lao Pako (1995–2004) I had started to sense similarities in early twentieth century French colonialism in Indochina and contemporary ecotourism in Laos, particularly their enthusiastic uses of the race- and development-focused narratives of traditional archaeology. This traditional archaeology was formed alongside the European colonial projects in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and was in the 1960s translated into the “processual” archaeology that is still today the predominant theoretical orientation of most archaeology done for research or contract purposes in mainland Southeast Asia.16 My academic home was and is in Sweden, where discussions have been much more in tune with the critical “postprocessual” archaeology. Postprocessual archaeology was established first in British archaeology in the 1980s, and was influenced by the more general “post” wave in humanities and social studies in the 1980s. While both traditional and processual archaeology strive to be objective and detached from contemporary society and their own situated positions, postprocessual archaeology focuses instead on the historical contingency of archaeological knowledge production.17 Spending months and months, year after year, in Laos, surrounded by a professional context of processual archaeology, but with my academic home attuned to postprocessual archaeology, I began to sense that some of the unfortunate structures of power and unequal opportunities that I identified and that disturbed me often relied on “objective truths” about cultural essence and progressive development found in archaeological writing influenced by either (in colonial times) traditional or (in more recent years) processual archaeology. Hence, my curiosity to learn more about the historical contingency of archaeology in mainland Southeast Asia grew stronger.18

The relationship between ecotourism and colonialism had already caught my critical attention at Lao Pako, not only because they both rely on traditional archaeological narratives and are attracted to threatened archaeological sites, but perhaps more because of the similar ways in which they claim to do one thing, and in practical reality do something quite different. This incongruence, the gap between rhetoric and practise in both French colonialism and ecotourism, has been a starting point for my analysis. I treat ecotourism and colonialism as two distinct, but fundamentally related discourses. Although they are part of different temporal, political, and societal contexts, the discourse of French colonialism in Indochina in the early twentieth century, and the discourse of ecotourism in the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century, have similar dependencies on archaeological narratives, and also share that incongruence between how they portray themselves and the practical consequences of their projects.

From this follows the central argument in all the essays of this book: that traditional archaeology, which plays an important part in the discourses of French colonialism and contemporary ecotourism, embodies ideals of racial or cultural essence and nurtures the idea of an absolute distance between the local community around Hintang and the Western coloniser or tourist. Throughout this book I argue that these notions of essence and distance are fundamental for the justification of the projects of colonialism and ecotourism, and are at the same time contradictory to the explicit benevolent and philanthropic aims of ecotourism as well as of early twentieth century French colonial policy. On a very basic level, ecotourism could be considered a neocolonial enterprise. Kwame Nkrumah has said that the “essence of neo-colonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality, its economic system and thus its political policy, is directed from outside”.19 According to this definition, ecotourism (as all other forms of development-oriented businesses directed to the third world) is indeed a form of neocolonialism. But this remains a flat statement as long as one does not engage in further critical enquiry into the similarities and differences between the two discourses. Messages of racial hierarchisation and development that were proudly displayed in naked explicitness in the French colonial project are no longer trumpeted so candidly. But just because the R word is never seen in ecotourism advertisements does not mean that racial hierarchisation and other oppressive structures resembling those of colonial times do not linger there; it just takes a more detailed digging in the discourse of ecotourism to find the signs and structures that give away its relationships with colonialism. And it takes detaile...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Saykham

- 3 Standing Stones | Stones Standing

- 4 “Nous n’avions plus qu’à faire des recherches méthodiques”

- 5 An Early Morning in July 1968

- 6 A One-Day Tour around the World

- 7 Time Travellers

- 8 Mlle Colani, Dr. Jones, and Me

- 9 Hat Ang: Spirit and Tale

- 10 Hintang Travel Ironies

- 11 Hintang [imperfect]

- Notes

- References

- Index

- About the Author