![]()

PART I

The Fall and ‘The North’

![]()

Chapter One

Building up a Band: Music for a Second City

Richard Witts

There are many good reasons for writing about The Fall, but I will take the worst. The story of The Fall helps us to understand the post-war history of Manchester where the story of Factory falls short of it. Yet in the five years between 2002 and 2007 there has been a concerted attempt to fix a stiff narrative frame around this city’s musical life. It has been applied by a cartel associated with Factory and keen to raise their ‘heritage’ status in the city’s cultural profile.

They have done so in order to delimit general sequences of events around the specificities of Factory Records, its founder the television journalist Tony Wilson (1950–2007), its original club night The Factory (1978–80), which was succeeded by its nightclub The Hacienda (1982–97), and the bands associated with the enterprise, chiefly New Order.1 By constructing and advancing a received post-punk narrative they have swept bands like The Fall out of that history. Yet the stories provided by practitioners and resources such as The Fall, John Cooper Clarke, New Hormones Records,2 Rabid Records, Band On The Wall3 or the Manchester Musicians’ Collective4 provide much richer accounts of impacts, scenes, activities, realizations and conflicts than the monochrome frame tightly set around Factory.

This retortive campaign grew from the dismay of Factory associates to a general media critique and marginalization of their venture in the 1990s. Such a reappraisal appeared to precipitate Factory Records’ bankruptcy in 1992 and the decline around that time of the fortunes of the Hacienda club, leading to its closure in 1997 and demolition in 2002. The singer of rival group The Smiths mocked Factory’s parochial character, while the most successful Manchester band of the 1990s, Oasis, had nothing to do with Factory. Sarah Champion’s modish book And God Created Manchester (1990) was a flippant survey of the scene that belittled Factory. She wrote of Joy Division’s impact, ‘[y]et even at their peak … hyped to death by writers like Paul Morley, it was nothing compared to the 90s Manc boom’ (Champion 1990, 11). In contrast, Champion hailed Mark E. Smith as ‘the Robin Hood of alternative pop’ (Champion 1990, 30).

Nevertheless four recent films have stamped the Factory story onto that of Manchester. Michael Winterbottom’s fictional 24 Hour Party People (2002) was succeeded by three films which circulated in the same year following Wilson’s cancer-related death: Chris Rodley’s documentary Manchester from Joy Division to Happy Mondays (BBC 2007), Anton Corbijn’s Control (2007) and Grant Gee’s documentary Joy Division (2007). Associated with these are no less than five books, chiefly Deborah Curtis’s Touching From A Distance: ian Curtis and Joy Division (2001), Tony Wilson’s 24 Hour Party People: What the Sleeve Notes Never Tell You (2002) and Mick Middles and Lindsay Reade’s Torn Apart: The Life of ian Curtis (2007).5 It is significant that the Factory story that is being told most loudly is not its near-comical decline (rendered in Winterbottom’s film) but that of the project’s abrupt rise, an ascent associated with the punctuation mark of Curtis’s death. It is Wilson’s death, however, that has provided the setting for the former to be iconically portrayed.6

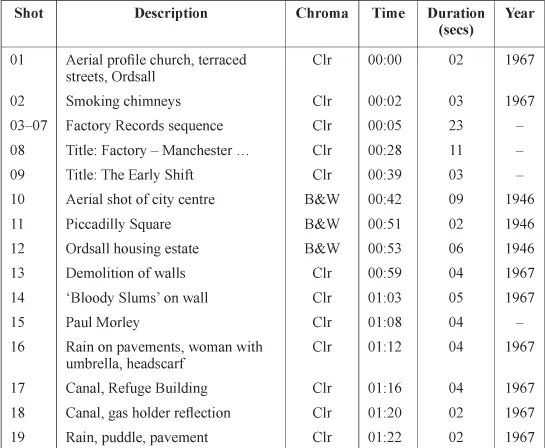

In each of the four films the Manchester conurbation of the 1970s is revealed as dilapidated, derelict and deprived. Row upon row of rain-spattered terrace houses are juxtaposed with shots of demolition hammers smashing them down while mucky kids mooch in the rubble. These highly edited images offer a bewildering message; were the people of Manchester and Salford living in caravans parked out of the film crew’s sight? The commentaries add to this depressing vista. In Rodley’s film journalist Paul Morley, in an image he must have taken years to hone, talks of how ‘the street lights somehow made things darker, not lighter’. Both Rodley and Gee, fine directors, told me of the limited range of post-war footage available of the conurbation. Most of what is accessible is held in the North West Film Archive. Both directors used a promotional film from its library shot in 1967 for Salford Council, titled The Changing Face of Salford. It is a ‘before’ and ‘after’ portrayal of improvements to the Ordsall area, and the rubble sequences come from the former section. I have made a table of Rodley’s opening shots (Table 1.1) which lists the sequences. The year of the filming of each segment is shown in the final column, and the whole reveals that Rodley used material shot over two decades to exemplify an impressionistic image of the central 1970s.

Table 1.1 Opening shots: Factory: Manchester from Joy Division to Happy Mondays (Chris Rodley, BBC4, first transmission 21.09.2007)

Meanwhile Tony Wilson in his book version of 24 Hour Party People set out the premise of the legend that continues to drive the Factory narrative, of how Factory provoked urban renewal:

This was the home of the Industrial Revolution, changing the habits of homo sapiens the way the agrarian revolution had done ten thousand years earlier. And what did that heritage mean? It meant slums. It meant shite … The remnants, derelict working-class housing zones, empty redbrick mills and warehouses, and a sense of self that included loss and pride in equal if confused measures. (Wilson 2002, 14)

In his demotic way he echoes Disraeli who wrote in 1844 that, ‘What Art was to the ancient world, Science is to the modern … Rightly understood, Manchester is as great a human exploit as Athens’ (Disraeli 1948). Having fashioned his trajectory – of how energetic Victorian emprise degenerated into post-industrial inertia – Wilson meshed his big picture with the small when, in Gee’s documentary on Joy Division, he led off, ‘I don’t see this as the story of a rock group. I see it as the story of a city’, adding, ‘The revolution that Joy Division started has resulted in this modern city … The vibrancy of the city and all the things like that are the legacy of Joy Division’, referring finally to ‘The story of the rebuilding of a city that began with them.’ This eschatology is endorsed by Gee’s ‘scriptwriter’ – though there is no script – Jon Savage, who wrote an essay to support the documentary in the Spring 2008 edition of Critical Quarterly, where his rather rambling discourse is there to back the inclusion of bleak grey photographs he took of Manchester buildings in 1977 (Savage 2008). It seems the sun never shone when Savage was around.

Conversely, let us shine a light on the facts. In the Manchester-Salford complex a period of avid metropolitan modernist planning took place in the 1950s and 1960s, with the objective, first laid out in the 1945 City of Manchester Plan, to eradicate a Victorian heritage of unplanned urban sprawl, one turned to further disarray by momentous wartime damage, and due to which Manchester lacked a vivid civic identity. Instead, the corporation planned a circle of satellite towns in the ‘garden city’ style of 1930s Wythenshawe, the hub for which would be an entirely regenerated city centre of impressive modern offices and prominent civic amenities, a flagship city to compete with other second cities like Chicago, Manchester’s model (HMSO 1995, 11–20).

Meanwhile the post-war pressure for council housing, and the lack of cash and resources, had led not to garden cities, but to a huge inner-city demolition programme. It began in 1954, and in connection with it came the hurried construction of overspill estates such as Hattersley and Langley (HMSO 1995, 24). Yet the re-housing schemes moved too slowly to meet both national and local objectives. Pressure to find cursory solutions was applied by both Conservative (1951–64) and Labour regimes (1964–70). The Corporation produced a second-phase Development Plan to erect new flats in the demolished spaces. Out of this sprouted those inner-city modernist monsters Fort Ardwick, Fort Beswick and the Hulme Crescents, all completed by 1972 and so hastily built that within two years many of the units were uninhabitable (Shapely 2006, 73).

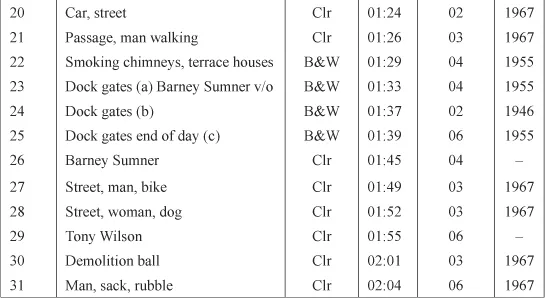

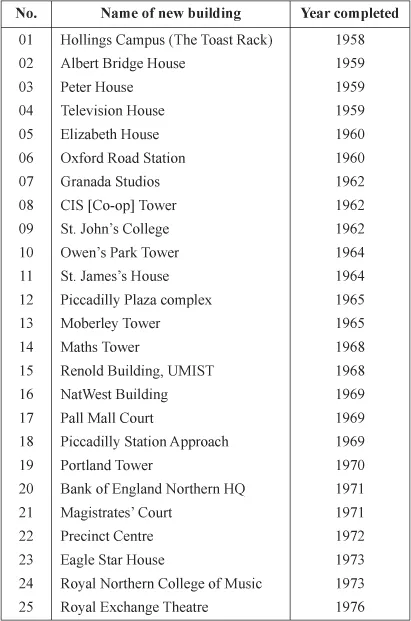

Nevertheless, from the start of the modernist development of Manchester in the mid-1950s until the postmodern shift in the mid-1970s, the vigorous scale of post-war neo-modernist commercial and institutional building resulted in 25 major modernist concrete, glass and steel buildings planned and built for the city complex. Table 1.2 lists these, starting with the surreal ‘Toast Rack’ domestic science college of 1958 (designed by a local civic architect), progressing through the Towers – such as the iconic Co-op of 1962, Owen’s Park 1964, Moberley 1965 and the Maths Tower of 1968 – to the Royal Exchange’s spectacular ‘space pod’ of 1976. This list is not inclusive and excludes, for example, the Arndale Centre, a massive but protracted and piecemeal retail development of the 1970s that was completed only in 1980.

Table 1.2 Manchester’s post-war modernist buildings

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 The 1976 ‘space pod’ in the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester. Images from the 1981 documentary Exchange

Figure 1.3 The Exchange Theatre today

However, many of the new concrete, steel and glass commercial and institutional buildings were neither varied nor coordinated enough to withstand public disapproval, a notorious example being the complex around the Maths Tower, the Precinct Centre and the Royal Northern College, where the ‘streets in the sky’ walkways were designed at different heights and so couldn’t be connected up. Thus, contrary to the view promoted in the Factory story, the image that Manchester presented to the world was not of a derelict city but of a comprehensively modern one – that had got it wrong. In fact, those were the words that Councillor Allan Roberts, chair of Manchester Council’s Housing Committee, expressed in 1977, adding, ‘Manchester’s not been doing its job.’ He admitted this after being cornered by burgeoning sets of tenants’ action groups whose campaigns, and the Council’s reactions, are well documented in Peter Shapely’s essay for the journal Social History (Shapely 2006).

The newly formed metropolitan county, the Greater Manchester Council of 1974, identified a clear solution, which materialized as the default postmodern architectural reaction of the period translated to the housing, amenities and image needs of the conurbation: that is, conversion of existing buildings rather than their demolition, identifying conservation areas such as Castlefields, marketing notions of legacy, pedestrianizing the city centre and making the initial attempts within the city to cage modernism within a bricked heritage, firstly and most sensationally at the Royal Exchange Theatre in 1976 and, in that sense following on, the Haçienda of 1982 and, nearby it, both the Cornerhouse visual arts centre and the Greenroom Theatre of 1983. In other words, Factory’s nightclub represented a commercial contribution to a public postmodern design project.

In terms of cityscapes and epochs, then, it appears to be in this postmodern context that we must place the birth of The Fall. Yet if we do so we slip into the same trap in which the Factory story has found itself caught. It is a coarse and quixotic determinism that conjures up the grids and correspondences needed to bond building sites and bands, civic plans and popular songs in the way that the Factory faction has done. The Fall certainly emerged – as did Joy Divison – from a set of circumstances tied to urban environment and class, but not wreckage and squalor. And in strictly musical terms we find in the births of these bands continuities from beyond the punk scene, such as Ian Curtis’s ‘German’ look and Smith’s Beat style (the bass of The Fall’s founder, Tony Friel, was called Jaco, after the jazz bassist Pastorius). Nevertheless, if we are to test whether Factory’s modernist claims suit the times, we must check how far a modernist aesthetic was already present in the city’s music scene.7 We can indeed identify bands spawned in the area at the time of the late 1960s that were progressive, utopian and internationalist in tendency: Barclay James Harvest, Van der Graaf Generator, 10cc. The short mid-1970s punk scene was definitely a cartoon-like negation of groups like them. But in reaction to that, the effervescent post-punk scene was in general more integrative, tending to mesh convention – such as song form – with experimentation, and to link punk’s gestural Luddism with a progressive curiosity for technology and sound production (on stage and in the studio). In the end it might be claimed that Van der Graaf Generator’s appearance at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology on 8 May 1976 was more influential to local post-punk aesthetics than the Sex Pistols’ two gigs at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on 4 June and 20 July of that year (see Nolan 2006).

Figures 1.4 and 1.5 The 1958 ‘toast rack’ – the Hollings Building, Fallowfield, Manchester, late 1970s

Existent co-ordinates in the mid-1970s air informed this post-punk integrative disposition. One such co-ordinate was the resurgent folk music scene of that time, through which singer-comedians such as Mike Harding and Bob Williamson propelled the Lancashire accent. Yet the conscious assertion of a local lingo, in line with the emergent promotion of a heritage culture, turned to deep embarrassment among progressive minds with the national success in April 1978 of Brian and Michael’s glutinous homage to local painter L.S. Lowry, ‘Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs’, and, while Ian Curtis of Joy Division maintained his affected American brogue in order to summon ghosts, others, like Mark E. Smith, gradually adopted ironized or embroidered accents, not in order to ‘represent’, but to stress the exceptional act of performance. Nevertheless, in 1978, Paul Morley would excitedly review in the New Musical Express (NME) a Manchester Musicians’ Collective gig under the headline, ‘These are the Mancunian Mancunians’ (see Morley 1978).

And when the conurbation started to re-assess its matchstalk inheritance it found, inside its dilapidated warehouses, post-punk musicians already there, practising. In ‘renting the heritage’, they were doing little for their health in those dank, freezing echo chambers, but they were working there together to prepare for gigs in old buildings such as The Squat (a derelict music college) or dishevelled clubs with dog-eared music licences such as the Cyprus Tavern and the Russell Club. Rehearsal rooms, 4-track studios such as Graveyard and Revolution, the ‘gentle giant’ tour manager Chas Banks, Oz PA Hire, promoter Alan Wise and Rabid Records were all part of the micro music industry that sprang up in a state of alternative enterprise, in which Factory acted out the role of Icarus. It was New Hormones, run by the non-Mancunian Richard Boon, that did succeed and that gave The Fall its start in a recording studio. Factory was not the brightest thread in the skein of yarns spun about those times.

Much of the city music scene, even Factory through its proclivity for Situationism, was driven by political critique, and in the experience of many the most class-conscious of all of the bands was The Fall. It always passed a common litmus test for the worth of a band at the time: would it play for free for Rock Again...