eBook - ePub

Archaeology of the Lower Ohio River Valley

Jon Muller

This is a test

Share book

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Archaeology of the Lower Ohio River Valley

Jon Muller

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Although it has been occupied for as long and possesses a mound-building tradition of considerable scale and interest, Muller contends that the archaeology of the lower Ohio River Valley—from the confluence with the Mississippi to the falls at Louisville, Kentucky – remains less well-known that that of the elaborate mound-building cultures of the upper valley. This study provides a synthesis of archaeological work done in the region, emphasizing population growth and adaptation within an ecological framework in an attempt to explain the area's cultural evolution.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Archaeology of the Lower Ohio River Valley an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Archaeology of the Lower Ohio River Valley by Jon Muller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Arqueología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Background to the Archaeology of the Lower Ohio Valley

Early Ohio Valley Archaeology

Pioneers

Archaeology began in the United States in response to a mystery—the mystery of the Mound Builders. In southern Ohio and elsewhere, early European settlers found huge mounds and long banks of earth piled up by some unknown race. When they asked the local native Americans who had built these monuments, they were told that no one knew. The settlers definitely felt that the native Americans themselves could not have built the mounds; to have accepted that would have considerably weakened their claim to the lands they were appropriating, after all. Silverberg’s Mound Builders of Ancient America (1968) relates the development of archaeological knowledge during this period. Although some of his interpretations are a little dated, he tells a fascinating story of the early archaeology of the areas surrounding the lower Ohio Valley. The archaeological remains of the lower Ohio Valley itself, however, attracted much less attention from early travelers and explorers. It was not entirely that the area had somewhat less spectacular remains than territories upstream. Even sites like Kincaid Mounds and Angel Mounds were not described until more than 70 years later than the earthworks of the state of Ohio. A few mounds were recorded here and there in early land surveys (e.g., Black 1967:5–6). For example, a Woodland period mound was noted near the Angel site during the first land survey of the locality (Black 1967:4). The most remarkable of the early accounts of the archaeology of the region is the detailed description of the Great Salt Spring in Zadok Cramer’s The Navigator (1814, 8th edition). This book was the major source of information about the river systems for travelers during the period of early settlement. It was used by nearly all persons who made the adventurous trip down the Ohio, and echoes of Cramer’s descriptions are to be found in many ostensibly original accounts of travels in the west. The trade routes to New Orleans were the first interest of settlers and merchants in the trans-Appalachian west, but soon there were numerous individuals who began to settle along the Ohio, rather than merely moving down it. Cramer was not insensitive to the needs of would-be settlers, and he also gave information on the major resources of the areas bordering the rivers. Among these were the various salt licks and springs of the lower Ohio Valley. In the case of the Great Salt Spring—near present-day Shawneetown, Illinois—Cramer not only described the newly developing European production of salt there; he also gave us a detailed and insightful account of aboriginal salt production as well. In this account, Cramer seems to have been one of the first to give a knowledgeable account of pottery manufacture and the addition of crushed shell to the pottery by what we now call “Mississippian” people. Cramer’s account is quite interesting:

At, and in the neighborhood of these works, is to be found fragments of ancient pottery of an uncommon large size, large enough, it is stated, to fit the bulge of a hogshead and thick in proportion. On Goose Creek in Kentucky, and in many other parts, in the neighborhood of salt springs particularly, similar fragments of ware are found which would induce a belief that its makers used it to boil their salt in. This is by no means improbable, some pots of similar composition but of a small kind for cooking, are still found in use among many of the tribes of American Indians, both southern and northern. (Cramer 1814:272)

Cramer goes on to describe modern vessels he had collected, and he also gives an interesting account of the use of burned and crushed shell in Choctaw pottery making. He relates these observations to the pottery found at the Great Salt Spring.

During this time, the debate over the identity of the “Mound Builders” was starting up in earnest. Many, perhaps most, of the persons who viewed the vast and magnificent earthworks of the Ohio Valley doubted that the American Indians could have been responsible for these. It was felt that the Mound Builders “had made much greater advances in the arts of civilized life” than had the native Americans, and that the size and complexity of the earthworks “clearly prove them to be the work of some other people” (Palmyra Register, January, 1818, and Palmyra Herald, February, 1823, as quoted in Brodie 1966:34–35). No less than a future president of the United States, William Henry Harrison, felt that the Mound Builders had been exterminated by the bloodthirsty ancestors of the Indians in a last great battle on the banks of the Ohio, where “a feeble band was collected, remnant of mighty battles fought in vain, to make a last effort for the country of their birth, the ashes of their ancestors and the altars of their gods” (Harrison 1839:11, as quoted in Brodie 1966:35).

Much of the investigation of archaeological sites in this region was simply done by curious landowners. One of the pioneer settlers of southern Illinois described his boyhood pleasures in the first half of the nineteenth century:

Sometimes we ascended the highest points of the Bluffs, clear of aught but grass, and opened old burial places on the loftiest tops, made by excavating the earth to a depth of two or three feet, as it appeared to us, then putting flat stones at bottom, sides, and ends and after depositing the bodies covering them up with similar stones. Usually the top stones were bare of earth or nearly so. Within, some bones and teeth were found, the teeth well preserved, the bones far gone in decay. (Brush 1944:32)

The long-term effects of this kind of recreational activity on the archaeological resources of the region can be imagined all too clearly. Few of these “stone box graves,” as they are called, and few of the mounds of the region have escaped at least some avocational examination with the spade. Not all of the curiosity about mounds was so casual, and some genuine pioneer efforts in archaeology characterized a few localities within the region.

The New Harmony Naturalists

During the time when many in the upper Ohio and elsewhere were beginning to undergo the nearly simultaneous development of archaeological science and the “Great Revival,” the area of the lower Ohio saw the establishment of utopian settlements in a number of locations. Most of these are of marginal concern here, but the second utopian community at New Harmony, Indiana, had considerable impact on the development of science in the new land. Robert Owen, a Scottish self-made man and utopian socialist, purchased the town of New Harmony from the departing religious “Harmonists” with the goal of establishing his “New Moral World.” A very substantial number of well-known and intellectually outstanding persons were attracted to this new experiment. Among these were William Maclure, Thomas Say, and Charles Alexander Lesueur, all famous naturalists.

On the journey to New Harmony on the flatboat Philanthopist in November, 1825, Lesueur’s attention was drawn to the mounds by a letter from Henry M. Brackenridge (Hamy 1968:39) and Lesueur made sketches of mounds along the Ohio. Hamy reports (1968) that Lesueur prepared careful copperplate illustrations for planned publications, but that he suffered from a writer’s block in preparing the accompanying text. Lesueur sketched the mouth of the Cumberland with the Ohio on a side trip (Hamy 1968:43) to Missouri and St. Louis. Lesueur and his traveling companion, Gehrart Troost, found “ancient dwelling places” in Missouri like those Lesueur would later investigate in the New Harmony locality. Reports of this trip were published in the New Harmony Gazette.

Lesueur carried out land surveys for the community on his return, and he located an “Indian burial ground on the banks of the Wabash on the hill of tombs [?], 168 to 170 feet above the low water of the river” (Hamy 1968:48), as well as recording the burial mounds in the Harmonist cemetery, “unfortunately already visited by vandals” (1968:48, Plate p. 49). Lesueur dug into the mounds and noted

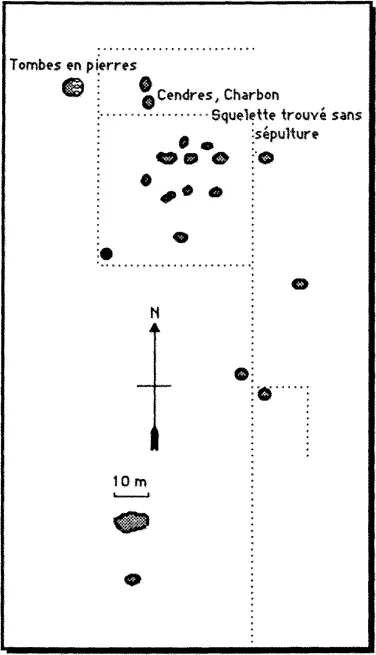

Figure 1.1 Plan of Hopewell burial mounds in the Harmonist cemetery, after a sketch by C. A. Lesueur (in Hamy 1968:49).

One of the mounds that I dug into north of the main one gave me fragments of pottery burned by use. The sandstone rocks which supported them had undergone the action of fire. Some bones and jaws of a stag, a tine of an antler that had been shaped with a cutting implement, and lastly a small blade of darkish flint, narrow and curved and sharp as a scalpel on both sides. (as cited in Hamy 1968:48)

A larger mound to the northwest (see Figure 1.1) had been excavated by the earlier Harmonist community and was reported to have contained

two rows of graves exactly oriented and formed of flat stones placed perpendicularly on the ground enclosing a funeral room, and surrounded by slabs of stone, each of which was six feet long. The bottom was unpaved and the stones that were found there were sandstone in a natural state. The ground was full of fragments of crumbly bones. (Lesueur’s notes as summarized in Hamy 1968:50).

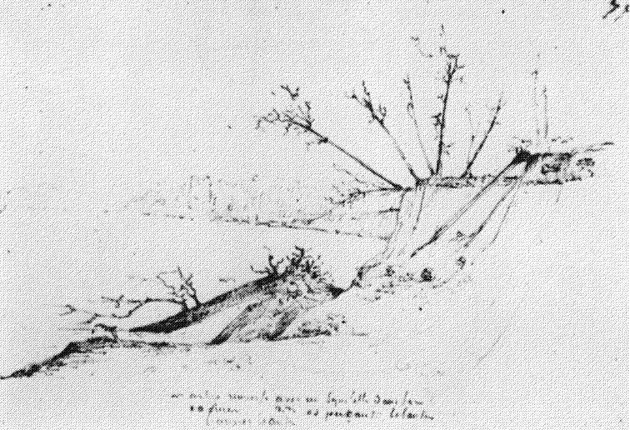

Figure 1.2 View of Bone Bank, March, 1828, sketched by C. A. Lesueur. (Courtesy of American Antiquarian Society.)

Lesueur dug the stone box graves without finding anything “worth noting” and he also found another skeleton that was not in a “tomb.” Plowing in the southern area showed the remains there of similar mounds, and Lesueur reported finding “a small stone which could be a chipped diabase” and “another that was globular and pierced in the center.” At a mound group 7 or 8 miles up the Wabash, Lesueur found “an oval cut flint with a sort of tongue . . . [which] appeared to have been used to dig the ground and was capable of being fastened to a handle.” Lesueur also noted that he felt the sources for these stone materials were from local gravels and limestones.

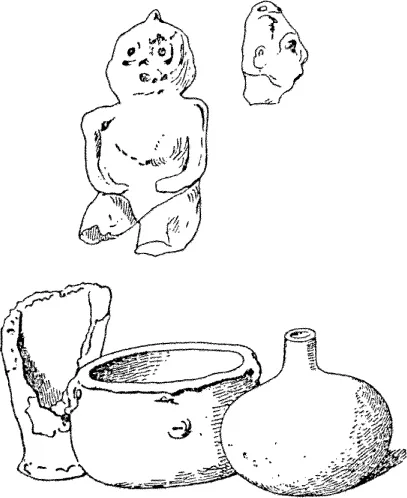

In March to December, 1828, Lesueur traveled from New Harmony to New Orleans in order to assure that his French pension would be continued (Hamy 1968:56). On the way, on March 29 to March 30, he carried out investigations of the large site called Bone Bank, at the mouth of the Wabash (Figure 1.2). Lesueur reported that the site had dark soil from 2 to 3 feet deep over a red sandy clay. The burials were in the dark soil, with the heads of those buried oriented to the east and feet to the west in several rows, as revealed in the eroded bank. Two skulls were obtained by Lesueur, but only one was sound enough to be preserved. It is reported by Hamy to be heart-shaped when seen from above (1968:57) and to have been brachycranic with an index of 93 (1968:92). Potsherds and pipes were found and are curated in the Museum of Le Havre in France. The pipes are reported by Hamy to be made of gray limestone in “the shape of a bird beak more or less exactly copied” (1968:58). The pottery is noted to have been shell-tempered and some of the pottery was “wicker impressed” (probably fabric-impressed salt pans; see Maximilian’s account of these as being molded in “cloth” or a “basket”). Lesueur’s collection also included materials, including Mississippian figures and adornos, brought to him by others (Figure 1.3; Hamy 1968:58). Lesueur also noted the presence of deer, fish, and dog bone, along with teeth.

Figure 1.3 Bone bank artifacts, sketched by C. A. Lesueur (from Hamy 1968:58).

On the same trip to New Orleans, Lesueur also opened some stone box graves at Cave-in-Rock. Several slabs were taken aboard the flatboat to line the fireplace. Near Golconda, a local doctor reported a well-preserved skeleton covered with bark in a cave. Lesueur and his companions stopped at the ruins of Ft. Massac, but they did not note the existence of the Kincaid Mounds across from the mouth of the Tennessee. Downstream on the Mississippi, Lesueur continued to note archaeological sites, including a 200-foot circular enclosure at Chickasaw Bluffs near Memphis, where he made collections. He visited the site at which mastodon bones and the Natchez human pelvis were found and collected a few bones (Hamy 1968:65). Lesueur repeated his visit to New Orleans five times, often sketching sites such as Bone Bank and a mound near New Madrid, Missouri. In 1832–1833, the visit of Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied provided an excuse to explore some local prehistoric sites. With the death of Thomas Say, his associate and friend, there was no longer any reason to stay in New Harmony. It is interesting to note that Say’s grave in New Harmony is a burial tumulus. Lesueur returned to France with his library, sketches, and collections. After a time, he became the director of the Museum of Natural History at Le Havre, where his collections reside today. Other collections from Lesueur’s work are reported (Vail 1939:59–60).

At the same time as Lesueur’s work, another New Harmonist, David Dale Owen—one of Robert Owen’s sons—was setting up what became the United States Geological Survey. He was trained by Maclure, among others. Lesueur worked with D. D. Owen in geological surveys, but he seems not to have been on very close terms with the Owens. Another son, Robert Dale Owen, was a prominent Indiana politician and played an important role in the foundation of the Smithsonian Institution. Although there seems to have been no lasting effect on the development of regional archaeology, the scientific method came early to the study of the region.

It is disappointing to note that the later Smithsonian archaeologists were not in touch with the New Harmony naturalists, and the archives of the Smithsonian show no evidence that the Smithsonian workers were aware of the early work in this area. Of course, the Smithsonian proper was not founded until after the era in question, but a search of the main archives reveals little evidence that Lesueur or Say ever corresponded with such individuals as Joseph Henry, the Secretary of the Smithsonian, although letters from Robert Dale and David Dale Owen are in the Smithsonian archives. No mention of archaeological materials is to be found in this correspondence, however. A fire in the 1860s, however, may have destroyed earlier records which would have shown closer connections than are now apparent. Given that Robert Dale Owen was one of the political figures responsible for the growth and development of the Smithsonian, it may seem surprising that there was not more in the way of archaeological investigations. Admittedly, the Owens were generally more interested in geology than in other natural sciences. Robert Dale Owen’s work as a congressman helped stimulate the law that finally put the Smithson bequest to work (Leopold 1940), amid a flurry of controversy about what kind of institution there should be. Perhaps the reasons for there being little attention to archaeology may be found in Owen’s statement: “I hold it to be a democratic duty to elevate . . . the character of our common school instruction. I hold this to be a far higher and holier duty that to give additional depth to learned studies, or supply curious authorities to antiquarian research” (debate on the Smithson bequest as quoted in Leopold 1940:225). Although Owen’s efforts to use the bequest for normal-school education were defeated, his relationships with the newly founded institution were reasonably cordial at first. Owen was named one of the three regents of the institution. One wonders if the disinterest in “antiquarian research” reflected family rivalries among the Owen brothers. Whatever differences there may have been, David Dale Owen was involved in the planning of the new Smithsonian. Robert Dale Owen’s political defeat in the election of 1847 and his subsequent removal from the position of regent led to the ascendency of Joseph Henry, who was opposed to many of the policies advocated by Owen, so some of the New Harmony group may have been somewhat on the “outs” with regard to the fledgling Smithsonian (Leopold 1940:246).

The Great Mound Race

During the 1850s, antiquarian interests were stimulated by excavations in the state of Ohio and elsewhere by persons such as Squier and Davis (1848). Although none of this work was really in the lower Ohio Valley, it was the source of popular (mis)conceptions of the “Mound Builders” or the “lost race” (presumably Caucasian) which was believed to be responsible for the earthworks of the upper Ohio Valley (see Silverberg 1968; Wauchope 1962; Willey and Sabloff 1980, for more extended discussions of this era). Most early work in the Ohio Valley was, as noted, largely concerned with the great Hopewell and Adena mounds of the state of Ohio. It is known that David Dale Owen retained some interest in the archaeology of the region and he visited archaeological sites in the period just before the Civil War. In general, little was happening. It is not clear why so little interest was shown in the antiquities in the lower Ohio. To some extent, the amount of archaeology done is a reflection of accessibility and population growth—and of the level of education of the settlers in a given area. From this perspective, it is clear why the New Harmony experiment was an exception in encouraging cultural practices more typical of larger communities. To be sure, the earthworks of Ohio are very spectacular; but both the Angel and Kincaid sites would seem to have been likely candidates for exploration, yet no notice was taken of them until later.

The Great Salt Spring near Shawneetown has already been mentioned as one of the first archaeological sites to be recognized in the region. This site was known to Lesueur and the other New Harmony naturalists. David Dale Owen brought the site to the attention of George Escol Sellers about 1854. In a series of visits, Sellers made collections of pottery at the site and conducted excavations. In 1859, Sellers sent samples of the materials he had collected to E. H. Davis, of the famous Squier and Davis team that had investigated so many mounds in Ohio and elsewhere (Squier and Davis 1848). Sellers also sent specimens to other scholars (Sellers 1877). A discussion of ceramic technology partly based on these specimens by J.W. Foster (1873) prompted a formal response by Sellers on the technology of the Great Salt Spring site in Volume XI of Popular Science Monthly (1877). In this paper, Sellers presented the first truly scientific archaeological report for the region. Foster, Charles Rau, and others looking at this material had interpreted the fabric-marked exteriors as resulting from basket molds which were burned off in order to fire the pot (Foster 1873:248). Sellers was moved to write his account of the site in order to refute this interpretation. He said, “My object in writing this article is to refute a theory that would attribute to the rude, prehistoric people of the Stone age a skill in manipulation than cannot now be approached by the skilled artisan of the present age” (1877:574). If there is one keynote to Sellers’ description of the site and its ceramics it is uniformitarianism. He insisted that the interpretation of the past be in line with processes operating today. His interpretations are fine examples of scientific reasoning. Among the conclusions he reached were that aboriginal pottery making had been done over molds, that the makers of the salt pans were also the persons buried in nearby stone “cists,” and that the main residential areas had been away from the springs on nearby hilltops. He noted, as others had not, that the impressions on the exteriors of the salt pan vessels were not basketry, but fabric. Sellers al...