eBook - ePub

In Search of Structural Power

EU Aid Policy as a Global Political Instrument

Patrick Holden

This is a test

Share book

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

In Search of Structural Power

EU Aid Policy as a Global Political Instrument

Patrick Holden

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Offering a clear and logical analysis of the panoply of European Union aid policies and a theoretically informed evaluation of their operation, Patrick Holden contends that the major thrust of EU aid policy is an effort to augment the EU's structural power through targeted political and economic liberalization. Although historically grounded, this book concentrates on EU aid to key world regions in the 21st century. As such, it provides a comprehensive and thought-provoking account of EU aid policy and will be of interest to a wide range of academics, students and policy makers.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is In Search of Structural Power an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access In Search of Structural Power by Patrick Holden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Theoretical and Methodological Framework: EU Aid and Structural Power

The relatively simple concept of structural power has great explanatory potential when applied to the EU’s international role. It helps us avoid an overly liberal and idealistic understanding of the EU’s role but also avoids an overly rigid and ‘hard’ definition of power, which would be inappropriate. Moreover, the structural power concept allows for greater differentiation, as is fitting for a complex and fragmented institution such as the EU. As outlined below it is by no means suggested that the tendency to seek structural power is peculiar to the EU. It is part of a general ‘will to power’ which percolates through the commercial and development policies of states and international institutions. The first part of this chapter is devoted to outlining this conceptual framework, starting with a brief exposition of how the EU is considered an ‘actor’ in international affairs and then discussing the concept of power in much more detail, drawing on a wide range of theories from international relations and international political economy. It then applies the structural power framework to the EU’s development policy and other activities, before discussing the role of aid instruments in particular. Following on from this, I outline more specifically how I evaluate the EU’s use of this instrument. This starts with a more general discussion of approaches to evaluating aid then discusses the methodology of the empirical studies in more detail.

1.1 The EU as an Actor

Although there is a growing acceptance that the EU is an actor worthy of study, it is necessary to clarify in precisely what sense this is the case. Defining what amounts to an actor in international relations is not unproblematic. Smith argues that the traditional theoretical prerequisites for a ‘strategic actor’ are unrealistically high. Rather than expecting an actor to be ‘monolithic, possessing a unified set of preferences and capable of unified action’ it is more reasonable to evaluate whether it is capable of ‘collective action’ and ‘strategic impact’ (Michael Smith 1998, 80). This is because the former criteria would, arguably, not be entirely fulfilled even by the major nation states. Bretherton and Vogler define the basic criteria for an actor in terms of degree of autonomy, coherence and capability (Bretherton et al. 1999, 18–23/36–42). Crucially, the EU takes different forms for different spheres of activity. In the case of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (including the European Security and Defence Policy), there is room for debate. Given its highly intergovernmental structure, whether the EU can be considered relatively ‘autonomous’ from the member state governments is questionable. Arguably even these intergovernmental structures for policy making have become so institutionalized, that the EU cannot be considered a mere mechanism to be instrumentalized by member states (Michael E. Smith 2003). But there are serious question marks over whether there is political autonomy from the United States, given the very close links many member states have with the Superpower and that unanimity is required for nearly all CFSP actions. Coherence is another big question mark. A lack of coherence was one of the essential reasons, according to Hill for the ‘capability expectations gap’ (Hill 1998, 23). The concept of coherence is, admittedly, qualitative and depends on what principles and objectives one has in mind (Tietje 1997, 211–214). Nevertheless it is clear that the EU has lacked unity at fundamental strategic conjunctures (most notably the Iraq invasion). Thus the questions asked by Hill are still salient. Certainly the CFSP is a fascinating case study of the Europeanization of EU policy-making (Tonra 2003), and its potential importance is enormous. However its impact in crucial strategic situations has been limited and it is still debatable whether actorness can be ascribed to the EU here. Without prejudging the issue, the argument here does not presuppose that the EU is an actor in the realm of traditional foreign policy. This focuses on another form of EU foreign policy (centred on its ‘external relations’ policies) where a much clearer case can be made.

In regard to EU external relations, the first pillar of the EU (the European Community) is predominant and it has solid, autonomous, supranational institutions such as the Commission and the Court of Justice. Also the Member State channels often use qualified majority voting which gives them a supranational dimension. All of this improves coherence. General studies of the EU’s foreign policy place a great weight on these civilian/external relations instruments (Hazel Smith 2002). Even Hill’s original critique noted the ‘highly structured political economy dimension of collective, autonomous, external, commercial and development policies’ (Hill 1993, 322). In Smith’s opinion the EU’s strategic capacity increased significantly due to further integration and the European Community (specifically the Commission) may be understood as the ‘strategic agent’ of the EU (Michael Smith 1998). In this sphere, enlargement and general trends in European integration have not necessarily reduced supranationality. In some cases the delegation of significant tasks to the European Commission has expanded. For example, the Nice treaty of 2000 gave the Council and Commission control over most aspects of trade in services, whereas before, this was the prerogative of individual governments. Likewise in administering aid policy the member state committees have adopted a less hands-on role, as their increased size (now 27 members), makes management impractical and so more power has been delegated to the Commission (interviews, European Government and European Commission officials, 2004–2005). Apart from the institutional set-up the less politically charged atmosphere in these areas of activity (as opposed to, for example, the Middle East conflict) allows for greater coherence and unity. Certainly there is prima facie evidence that the EU has significant capability here and thus it can be considered an actor, but what kind of power may this lead to?

1.2 Concepts of Power

This section will first discuss popular ways of conceptualising the EU’s power before outlining a more comprehensive typology of power and situating the concept of structural power within this framework. One of the original paradigms for the EU’s role in the world was that of a civilian power, which encapsulated the EU’s use of non-military instruments to project its influence on the international stage (Duchêne 1972). Of course, due to the ESDP, the EU is no longer a purely ‘civilian power’ and many contemporary scholars seek to go beyond this term (Whitman, 1998), although the concept is still found useful (Orbie 2006). Deeper criticisms include that the civilian power approach is predicated on a conservative ‘interest-based’ ontology of the international system (Manners, 2004). This may or may not be a problem as long as these limits are understood and indeed the concept can be adapted to incorporate constructivist insights. Nevertheless it is true that the term has strong ‘normative’ assumptions (and distinctly echoes the French idea of a ‘mission civiliatrice’), which are problematic. Even when the civilian power paradigm was introduced others were discussing the EU’s world role in much more critical terms (Galtung 1973). A concept of power is needed that addresses these critical arguments and that has more of an analytical edge. Some similar criticisms may be made of Nye’s concept of ‘soft power’. It was originally described in very broad terms as ‘non-command power’ and is now conceived as the influence and security benefits which stem from the attractiveness of a state or group of states (Nye 1990; Nye 2004). It is a useful descriptive term but again can be a little vague. This is not surprising as the concept is part of a public debate on the use of aggression in US foreign policy (Nye 2005). This ‘rhetorical’ utility of the term partly explains why it is not such a precise analytical tool.

Manners develops the ideational underpinnings of ‘soft power’ and the ethical implications of ‘civilian power’ with the notion of normative power (Manners, 2002). This conceives the EU as a changer of norms in the international system, partly through its very existence (see also Maull 2005, 778) and partly through conscious efforts. As Manners outlines, normative power can encapsulate various critical approaches to theorising international politics, one example being the neo-Gramscian concept of ‘ideological power’ further discussed below. Normative power is more commonly related to social constructivist approaches. These have been particularly prevalent in studies of the EU’s international role, partly due to the clear importance of shared norms, socialization processes, discourse and identity in European Integration (Haas 1958; Christiansen et al., 1999). Constructivist approaches to Europe’s international role focus on its use of discourse and dialogue to spread moral norms regarding values such as human rights, and multilateralism, a clear form of normative power. Yet many would argue that social constructivists in general have tended to underemphasize the power dimension in the study of IR (Barnett and Duvall 2005, 40) and this is certainly true regarding the study of the EU’s international role. Again this is partly because constructivist studies of European integration have underplayed the issue of power, probably as a reaction to excessively interest-based and power-centric theories of integration such as Moravcsik’s liberal intergovernmentalism (Moravcsik 1993).

This emphasis on the role of norms, values and identity in EU foreign policy is certainly valid and of intellectual interest but an exaggerated focus on values may blind us to the importance of more material configurations of power. Also a ‘normative power’ approach can fall into the trap of implicitly accepting the loftier rhetoric of EU policy-makers (Sjursen 2006, 2). In fact there is strong evidence that normative considerations in EU foreign policy are interacting with and essentially shaped by self-interest considerations: ‘The way in which norms are conceived and incorporated into external policy reveals a certain security-predicated rationalism’ (Youngs 2004, 435). It is argued here that they also reveal a certain power-centred rationalism. Thus a stronger conception of power is needed but conventional realism has little relevance and therefore ‘new realist’ IPE approaches have much to offer. Before discussing this however we must look more comprehensively at the concept of power.

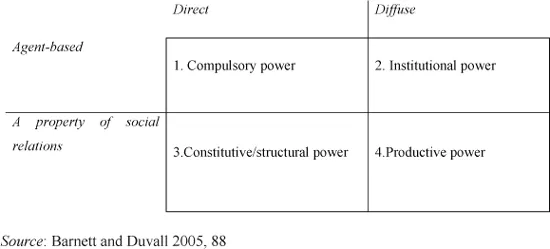

Barnett and Duvall’s taxonomy of power

It will already be apparent that this book uses a relatively broad definition of power, as opposed to the more explicit coercive notions of power. At the same time, if nearly all forms of persuasion and discourse are regarded as an exercise of power the concept uses its usefulness. Barnett and Duvall’s definition is a useful starting point, ‘power is the production, in and through social relations, of effects that shape the capacities of actors to determine their circumstances and fate’ (Barnett and Duvall 2005, 42). As they argue, this definition is broad enough to accommodate many forms of power but not so broad as to render it applicable to all forms of social interaction and thus lose its analytical usefulness. They outline, based on this definition, a comprehensive taxonomy of the various concepts of power, which offers a useful basis for discussing structural power (although their vocabulary is different). They derive four primary types of power from two sets of variables, see figure 1.1. The first relates to the standard agent-based (power exercised by an agent) versus social relation (power as a feature of a relationship) distinction. The second is whether power must operate ‘directly’ or in a more diffuse manner. This is a more problematic distinction but the four types are worth treating discretely as a basis for further discussion.

The first type of power is the simplest – power exercised by a specific agent over another – and needs no more explanation. The second type also involves agency in that it involves an agent setting the rules (and agenda) of institutions, for example one great power setting the rules of an international organization or a less formal ‘regime’ (Krasner 1983). This institutional power is relatively diffuse in that it takes effect (shapes the choices of others) over the long-term in a variety of instances. Such approaches to power are used by mainstream neo-realists and neo-liberal institutionalists (Ibid; Keohane and Nye 1989).

Figure 1.1 Barnett and Duvall’s categorization

What they call structural/constitutive (referred to here as ‘purely structural’) refers to the power relationships inherent in a social structure beyond any conscious exercise. One example they give is the Marxist understanding of the capitalist system as a social structure that automatically empowers the owner of capital and dis-empowers the worker. One example from an international relations perspective, is World Systems Analysis. This divides the world into centre, semiperiphery and periphery based on long-term historical processes and the spatial relations of the contemporary mode of production (Caporoso 1989, 103–109). Capacity and choice is primarily a function of a state’s location in this system and thus the system itself ‘constitutes’ power. There are also more ideational concepts of power along these lines. The aforementioned Neo-Gramscian school posits that intellectual structures and normative principles (the prime example being neo-liberal economic philosophy) intrinsically empower and dis-empower certain groupings (Cox 1983). Thus ideological hegemony has material and institutional effects, benefiting certain classes and countries. While many constructivists do not focus on power, systemic constructivism can clearly be related to structural power. This focuses on how international normative and ideational structures determine identities, roles and interests. Just as the patriarchal social system intrinsically constituted gender identities and roles (empowering the male and dis-empowering the female) so the international social structure constitutes identities and roles. Obviously the Westphalian ideational structures privileged states as actors over other forms of organization; the ideational structures of sub-systems like the Warsaw Pact communist block privileged the role of the Soviet Union and its leadership (Wendt et al. 1995). Changing ideational structures could empower or disable other actors. Wendt stresses that the underlying social structure in which states are embedded help determine the interests and capabilities of states. In other words the underlying social structure is a deeper form of power and thus ‘power is constituted primarily by ideas and cultural contexts’ (Wendt 1999, 97).

Their final form of power is also conceived in terms of social relations but ‘productive power’ is more diffuse and multi-directional than the previous form which is basically uni-directional with clear winners and losers (capitalist-worker, core-periphery).1 Such conceptions of power are related to post-modernist and post-structuralist thought. Hardt and Negri’s understanding of an a-territorial ‘Empire’ empowering and disempowering at multiple levels, is one example of the application of this to international relations (Hardt and Negri 2001). This form of power is not further discussed here as this book is based on a more conventional ontology, see section 1.5. ‘Productive power’ can of course remain in the background as an alternative understanding to the arguments posited.

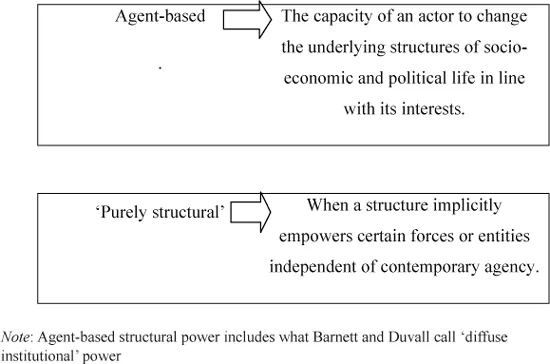

As the authors of this typology accept, in practice these different forms of power will interact. Of particular interest is the link between purely structural power and question of agency, see figure 1.2. The former type of power can be sought in the same way that actors pursue ‘mileu goals’ (Wolfers 1962). The post World War II global economic system was to a large extent created via US agency in developing international economic governance, European integration and Japan’s economic revival (Panitch 2005, 106). Thus the US was forging a system whose structural qualities would privilege its role. Likewise, ideological hegemony, or roles and identities with power effects, are projected by actors (states, international organizations etc.) Indeed this is the essence of the structuration principle, that agents and structures are co-constitutive. Also what Barnett and Duvall call agent-based institutional power can also be described as structural in that it is structural in effect; the rules created shape the choices of others. Accordingly, what is needed is a concept of power that incorporates structure and agency.

Strange’s conception of structural power

Strange defined structural power as the ‘power to shape and determine the structures of the global political economy within which other states their political institutions, their economic enterprises and (not least) their scientists and other professional people have to operate’ (Strange 1994, 24–25). This can be purely structural, for example, the mobility and size of private finance in the current system means that states and other agents must respond to its cues and must obey rules regarding property rights/monetary systems and thus ‘capital’ has structural power. Also one state (the US) may be deemed to have structural power in that its sheer economic size relative to others (and their dependency on its markets) means that its internal rules and systems will spill over to others whether it wants to or not. A region or state may have structural power in trading terms if (beyond any discussion of purpose) its size leads to a gravitational attraction and inherently asymmetric trading relationships. However Strange’s theory is not based on a structuralist/determinist ontology and it also includes agents that possess the capacity to mould the formal institutions and deeper material and ideational structures of the international system (Ibid). Thus in her view a state like the US possessed and exercised structural power in terms of the ability to mould economic, financial and other systems. Indeed a major theme was that the US had the responsibility to act to change the international system. This is significant for two reasons. Concepts of structural power are often criticised for ‘not sufficiently stressing the fundamental agent reference of power’ (Guizzini 1993, 469), but while this may be true of some approaches is not so of Strange. Also, if structural power can be an attribute of an actor (and can be exercised by it) it can also be sought by an actor.

Figure 1.2 Different meaning of structural power

Strange sub-divided power into four structures (1994). These are not applied in the empirical analysis but are worth noting as the principle that structural power can be heuristically divided into distinct (but interconnected) sectors is important.

The primary structures (of which only two are economic) delineated are:

• Production: productive economic activity (not limited to ‘industry’).

• Finance: the allocation of credit.

• Security: viewed in a traditional sense. Structural power here would include technological capacity and the strategic position of an actor.

• Knowledge: this is used in two senses, relatively technical issues regarding information and scientific capacity but also deeper issues regarding perceptions and beliefs. This can be clearly related to Neo-Gramscian and Constructivist approaches. Although it is fair to say that Strange did not fully explore the epistemological implications of this form of power (Tooze 2000, 188).

Structural power is particularly useful as a framework for the following reasons. It captures the relationship of agency and structure well in that it, obviously, appreciates the importance of structural factors but is far from any kind of tautological structuralism. It allows for agency and purpose. Related to this, structural power analysis has a strong political economy dimension (appropriate given the crucial role of economics in the EU’s external relations) but does not fall into economic determinism. The concept allows for a nuanced approach in several ways. Although it is obviously power-centric it is not as extreme as the neo-realist approach that o...