eBook - ePub

Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies

Third Edition

- 710 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies

Third Edition

About this book

George Frison's Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains has been the standard text on plains prehistory since its first publication in 1978, influencing generations of archaeologists. Now, a third edition of this classic work is available for scholars, students, and avocational archaeologists. Thorough and comprehensive, extensively illustrated, the book provides an introduction to the archaeology of the more than 13,000 year long history of the western Plains and the adjacent Rocky Mountains. Reflecting the boom in recent archaeological data, it reports on studies at a wide array of sites from deep prehistory to recent times examining the variability in the archeological record as well as in field, analytical, and interpretive methods. The 3rd edition brings the book up to date in a number of significant areas, as well as addressing several topics inadequately developed in previous editions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies by Marcel Kornfeld,George C Frison,Mary Lou Larson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | |

THE NORTHWESTERN PLAINS AND THE CENTRAL ROCKY MOUNTAINS An Ecological Area for Prehistoric Hunters and Gatherers |  |

INTRODUCTION

The Great Plains of North America constitute a large share of the continent, extending north and south from well into Canada to the border of Mexico and from the base of the Rocky Mountains on the west to the Eastern Woodlands (Wedel 1961:20–45). The Rocky Mountains likewise extend from northern Canada to Mexico and from their eastern boundary with the Great Plains to their more diffuse western boundary with the Northwest Plateau, Great Basin, and other physiographic regions. Actual boundaries between the Plains and Rocky Mountains are somewhat flexible, depending on the reactions to the area by the particular observer. There are some places where one can almost point to a line separating the Rocky Mountains and the Plains. Elsewhere on the western border of the Plains, mountain ranges extend deep into the Plains and often form intermontane basins, obscuring the line of demarcation. This is especially true in the case of the Central Rocky Mountain region. The eastern boundaries of the Plains are even less distinct, since there is none of the contrast formed by mountain slope and flat plain. Rainfall generally increases gradually to the east across the Plains, accompanied by lushness of the flora; the same is true with increasing elevation in the mountains. There is no sharp line of demarcation separating short-grass plains from tall-grass plains and the latter from Eastern Woodlands. Both short- and long-term changes in annual precipitation cause these boundaries to shift from time to time (Wedel 1961:20–45).

The seasoned Plains traveler can always detect the subtle difference that identifies the Plains. Prehistorically, the area was at the periphery of eastern cultural developments such as Hopewellian and Mississippian, but both influenced the peoples of the Northwestern Plains. Rainfall, frost-free days, and the available technology apparently held back the development of agriculture, limiting Plains horticultural efforts mostly to the floodplains of the rivers on the eastern margins. The Plains villagers living there may have been on the threshold of greater cultural developments when their efforts were disrupted by European incursion.

Various landforms, including stream valleys, uplifts, erosional remnants, and other less important features resulting from geologic processes, form integral parts of Plains and Rocky Mountain environments. These landforms provide relief to an otherwise monotonous and rather drab scene, and are reminiscent of oases in the desert. They often appear rather abruptly among seemingly endless rolling hills with little change in flora or fauna. The sudden appearance of a stream flowing from the higher elevations, or a spring in an arroyo with the surrounding green grass, trees, and shrubs, changes the entire aspect of the country. Without these niches or microenvironments, the region would not be the same and would certainly be less bearable for humans.

Such niches were every bit as important to the prehistoric inhabitants as to the present ones, animals as well as humans. The buffalo were grazers, but they had to go to water regularly, and they liked to stand in water and roll in dirt wallows. They sought shade on hot summer days, and they sought the protection of cut banks and brush thickets during winter and spring blizzards. Many animals, such as deer and mountain sheep, were not true open plains dwellers and favored areas of topographic relief, such as buttes, arroyos, river breaks, and dissected mountain slopes. Pronghorn do well with the forbs available on the sagebrush steppe of the intermountain basins to the west. These animals were important to the prehistoric economy. Human survival required a planned and careful utilization of the entire ecosystem; the instinctive behavior of the animals brought about culturally conditioned responses on the part of the humans.

The day-to-day life of the Plains and Rockies was generally harsher than life in adjacent geographic areas. Summer sun and winter storms were (and are today) brutal, reaching intensities from which there is little protection in the natural environment. Although there are differences in mean annual temperatures from north to south, a blizzard on the open areas of the Southern Plains can cause every bit as much discomfort as one on the Canadian border. However, both the human and animal populations were able to adapt to these harsh climatic conditions.

Though the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains of North America are marked by certain elements that distinguish them from adjacent areas, there is great internal diversity (e.g., Wood 1998). Depending on the person’s home ground, a great many descriptions of the Plains are possible. Early on William Mulloy (1958) realized and described the great diversity of Northwestern Plains physiography. The short-grass plains are different from the tall-grass areas; the glaciated areas east of the Missouri River contrast sharply with areas to the west; small intermontane basins in the rain shadows of mountain ranges differ from the more open and expansive river basins. As a result, there is no single prehistoric ecological or cultural model that will suffice for the entire area.

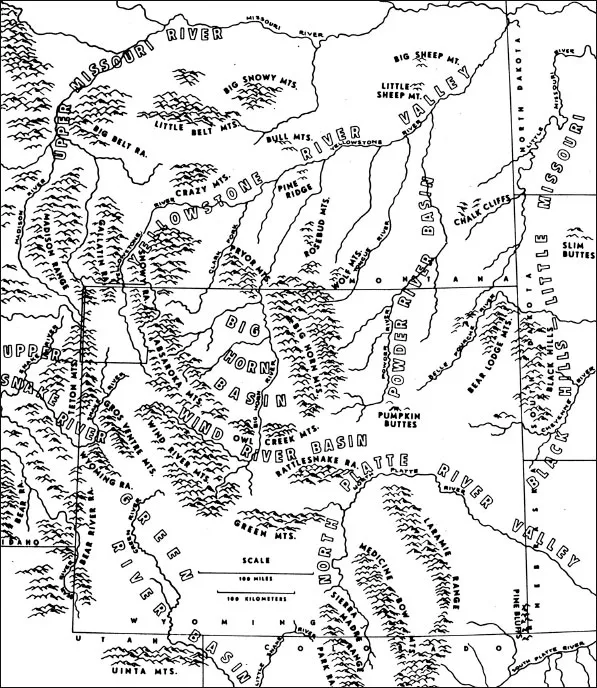

This volume attempts to document only the prehistoric cultures of what is commonly called the Northwestern Plains (Mulloy 1958; Wedel 1961) along with the adjoining Rocky Mountains. For the purposes of this volume, the terms “Northwestern Plains” and “Rocky Mountains” refer to the archaeological culture area that encompasses the physiographic regions of the High Plains, Northwestern Plains, Central Rocky Mountains, portions of the Northern and Southern Rocky Mountains, the Black Hills uplift, and the Wyoming Basin. The area includes all of Wyoming in addition to southern Montana, eastern Idaho, southwest North Dakota, western South Dakota and Nebraska, and the area along the northern border of Colorado (Figure 1.1). In this volume, we also discuss pertinent data from the surrounding region. Although the boundaries are somewhat vague, the core of this region covers an area of more than 200,000 square miles that demonstrates considerable ecological diversity over short distances but shows strong suggestions of cultural homogeneity during prehistoric times. The area is extensive enough to detect many subtle changes in patterns of prehistoric exploitation, yet small enough to handle in terms of a research area.

The Northwestern Plains and surrounding regions demonstrate a wide variety of landforms. Mountain ranges and lesser uplifts project abruptly from the floor of the Plains. Many intermontane basins are at elevations above 7000 feet (2134 m); others are at less than 4000 feet (1219 m). Some areas of the open High Plains are subject to almost constant wind, whereas other areas are better protected. Floral changes are rapid in response to changes in elevation, precipitation, soils, and topography. Straddling both sides of the Continental Divide, the mountains adjacent to the Northwestern Plains are the source of many large rivers, which were avenues of human group movements from many directions. It is a unique area that requires careful analysis to understand its potentialities and failings in providing a subsistence base for past human populations. But no amount of analysis can entirely replace a long-term familiarity with the area during all seasons. Prehistoric hunters and gatherers had to deal with the adverse times of year as well as with the favorable ones.

Figure 1.1 Major landforms of the Northwestern Plains and Rocky Mountains.

Different areas within the Northwestern Plains and Rocky Mountains demonstrate ecological changes over short distances. The southern part of the region is dominated by an area of intermountain basins to the west of the Great Plains. The Wyoming Basin, sandwiched between the Central and Southern Rocky Mountains, is only interrupted from a nonmountainous passage between the Great Plains and the Great Basin by the Wasatch Range in Utah. While some consider the Wyoming Basin to be part of the Rocky Mountain System because of its location between the Central and Southern Rocky Mountains others consider it an extension of the Great Plains, with its comparatively lower altitude and unique character. Within the Wyoming Basin, there are several distinctive sub-basins.

The Laramie Basin in southeastern Wyoming is over 7000 feet (2134 m) above sea level and is composed mainly of rolling hills, with some areas of “breaks,” or rough, deeply dissected landscapes. Transitional between the Plains on the east and intermountain basins to the west, it has a good grass cover, with some patches of sagebrush and greasewood in places. Playa lakes are common, although deeper lakes may hold water continuously or nearly so. The wind keeps large areas bare, allowing animals winter access to feed but forming deep snow drifts in arroyos and depressions.

Moving further west in south-central Wyoming, we find that elevations are lower and grass cover is not as good as in the Laramie Basin, with more sagebrush in evidence. This area is marked by some extremely rough country caused mainly by the deeply trenched North Platte River and its numerous permanent and intermittently flowing tributaries. The Hanna, Great Divide, Green River, and Washakie Basins and the Red Desert area further west in the Wyoming Basin lack good grass cover, but to some extent this may reflect overuse by livestock since the latter part of the nineteenth century. Here sagebrush, greasewood, and salt-tolerant desert shrubs form a vegetative mosaic throughout the lower elevations, with juniper, mountain mahogany, pine, and sagebrush in surrounding foothills.

One of the more unique aspects of the western Wyoming Basin is a large complex of active and stable sand dunes that span much of the area from southwest to northeast (Ahlbrandt 1974; Knight 1994:120). These dunes add to the ecological diversity present in the area today and formed an integral part of the environment in which the prehistoric inhabitants of southwestern Wyoming lived. The dune fields provide an environment that produces greater plant biomass than the surrounding sagebrush steppes (Knight 1994:122). Moisture falling on large sand dune areas often percolates through the sand to an impervious level and then comes to the surface in interdunal ponds. Some of these are large and provide water and green feed to animals who seek out these areas. Dune areas existed in varying sizes and distributions throughout at least the past 12,000 years in southwestern Wyoming and are found associated with buried artifact-bearing deposits.

To the south of the Green River Basin, the Green River flows into rough canyon country on the northern periphery of the Southwest and joins the Colorado River in western Colorado. The east–west trending Uinta Mountains, mostly in Utah, bring an end to the High Plains–like country of the southern Bridger Basin, located in extreme southwest Wyoming. A series of north–south trending ranges and divides on the Wyoming–Utah border, including the Bear River Divide, the Salt River Range, and the Wyoming Range, form the western border of the Green River and Wyoming Basins. West of this, the rivers flow into the Great Salt Lake. To the north of the Uinta Mountains, the character of the country changes gradually from plains to mountains in northwest Wyoming with the Wind River Mountains, the Gros Ventre Range, the Absaroka Mountains, and the Teton Range. Jackson Hole is nestled between the Teton and Gros Ventre ranges and is part of the upper Snake River drainage, which begins on the southern edge of the Yellowstone Plateau and flows south, west, and then northwest into the Columbia River. Yet, for all its mountain character, there are open, sagebrush-covered flats bordering the Snake River in Jackson Hole.

The Snake River Plain and adjoining areas in southeastern Idaho present an ecological and archaeological situation that bears a close relationship to the Northwestern Plains. The Yellowstone River, beginning at Yellowstone Lake, a large body of water at an elevation of 7200 feet (2195 m) on the northern part of the glaciated Yellowstone Plateau, drains north into Montana and then turns east and flows diagonally across Montana and meets the Missouri River at the Montana–North Dakota border. The headwaters of the Madison and Gallatin rivers also begin on the Yellowstone Plateau and flow north into Montana and then directly north to Three Forks and the beginning of the Missouri River. West of the Yellowstone Plateau in southeast Montana lies the Jefferson River, the third major stream that forms the Missouri River. The Sun and Milk rivers join the Missouri from the north, having their source in the Northern Rocky Mountains.

The Plains-like country continues t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 The Northwestern Plains and the Central Rocky Mountains: An Ecological Area for Prehistoric Hunters and Gatherers

- 2 The Archaeological Record for the Northwestern Plains and Rocky Mountains

- 3 Methodology for the High Plains and Rocky Mountains: Animal Behavior, Experimentation, and High-Tech Approaches

- 4 Mammoth and Bison Hunting

- 5 Prehistoric Hunting of Other Game and Small Animal Procurement

- 6 Prehistoric Lifeways and Resources on the Plains and in the Rocky Mountains

- 7 Communities and Landscape

- 8 A Myriad of Life’s Necessities

- 9 Paleoindian Flaked Stone Technology on the Plains and in the Rockies

- 10 Northwestern Plains and Rocky Mountain Rock Art Research in the Twenty-first Century

- 11 Advances in Northwestern Plains and Rocky Mountain Bioarchaeology and Skeletal Biology

- 12 Lithic Resources

- 13 Final Thoughts and Remarks

- References

- Site Index

- Subject Index

- About the Authors and Contributors