- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Science of Human Origins

About this book

Our understanding of human origins has been revolutionized by new discoveries in the past two decades. In this book, three leading paleoanthropologists and physical scientists illuminate, in friendly, accessible language, the amazing findings behind the latest theories. They describe new scientific and technical tools for dating, DNA analysis, remote survey, and paleoenvironmental assessment that enabled recent breakthroughs in research. They also explain the early development of the modern human cortex, the evolution of symbolic language and complex tools, and our strange cousins from Flores and Denisova.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Science of Human Origins by Claudio Tuniz,Giorgio Manzi,David Caramelli in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Human Origins: Just a Primer

We, the Primates

The origin of the species Homo sapiens1 (our own species, as it was classified by Linnaeus in 1758) is just another episode, in some ways a bit bizarre, in the natural history of a group of creatures known (after Linnaeus) as the primates. This group is an order of the class Mammalia, which includes lemurs, monkeys, and apes. As such, we, the primates, bear imprinted in our physical appearance, in our physiology, and in our DNA all the characteristics that are shared by these kinds of vertebrates. Indeed, we can regulate our body temperature and usually our bodies are covered with (more or less visible) hair; specifically, we have infants that develop inside the mother’s body and are nurtured for a certain period after birth.

The fossil record tells us that the story we humans have in common with the other primates dates back to earlier than 65 MYA,2 at the end of the Mesozoic, the age of the dinosaurs. Since then, small nocturnal animals—insect eaters, with pointed noses and hairy bodies— emerged from the common stock of all primitive mammals, giving rise to the adaptive radiation that led to a huge variety of primates. Although many of these primates are now extinct and known only from their fossils, more than 400 species are still living today. Through the colonization of forest environments, primates have taken over the entire planet and developed a myriad of forms. In fact, although today primates are distributed almost entirely (the most notable exception being our own species, H. sapiens) within the tropical regions of South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia, fossils of extinct prosimians, monkeys, and apes have been found also in North America, Europe, and northern Asia.

An examination of the evolutionary history of the primates is beyond the scope of this book. But we must remember that after 35 MYA there was a remarkable expansion of the group of primates known as the Hominoidea: the apes. The current representatives of this group are a few taxa that evolved from a number of other extinct forms and that exhibit many affinities (both morphological and genetic) with our own species: the gibbons (thirteen species), the Asian great apes (the orangutans), and the African apes (gorillas and chimpanzees). The origin of extant Hominoidea, including ourselves, is documented by a large amount of fossil evidence scattered throughout Africa and Eurasia during the Miocene. It is in this context that we must look for taxa close to the origin of our direct ancestry.

From this point of view, one of the hypotheses formulated in 1871 by Charles Darwin3 proved to be valid. Darwin believed that the origins of H. sapiens were to be found in Africa, since the African great apes (gorillas and chimpanzees) are more similar to us than the Asian orangutans and all other primates. In the last decades, molecular biology has fully confirmed this intuition, adding a quantitative approach (unimaginable in Darwin’s time) to assess the evolutionary divergence dates with a method known as “molecular clock,” as we will discuss in other sections of the book. Thus we know that the common ancestor between the chimpanzees and us lived around 6 MYA; the separation from the gorillas occurred a little earlier (about 8 MYA), and the orangutans separated from this lineage before 14 MYA. This implies that at some point in time some kind of African proto-ape has divided into different populations isolated from one another, probably under the influence of environmental changes. Some of these groups evolved into different species, giving rise to the trajectories of the extant gorillas, chimpanzees, and human beings. Nevertheless, the late Miocene ape from which this story begins has yet to be identified on the basis of the fossil record. What we know for sure is that among its descendants, the ape that is the most distant from the original forest and arboreal adaptation is H. sapiens, the only surviving species of a lineage that began to develop around 6 MYA.

Still in the Forest, but ...

Based on the fossil record of the last 6 or 7 million years, we can identify about twenty extinct species of humans and proto-humans, each representing more or less direct ancestors of today’s humankind. The oldest ones were distributed throughout Southeastern Africa, from the Horn of Africa down to the Cape. They were found mostly in Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa, with two exceptions, both located around 2,000 kilometers to the northwest in Chad.

So, for a few million years (between 6 and 2 MYA), our evolutionary history took place mainly in the geographic area marked by the Great Rift Valley (GRV), the well-known tectonic trench characterizing East Africa, as well as in South Africa and (perhaps more occasionally) in Chad. The development of the GRV has induced the rise of mountains and the creation of deep depressions, which are punctuated by large lake basins. This area has been selectively affected by the progressive drying out that has characterized the history of our planet over the last 10 million years, especially during the last six. Today at the same latitude, but in West Africa, there are dense equatorial forests where chimpanzees and gorillas survive. To the East there are now large extensions of grassland (savannah), dotted with trees and shrubs or interspersed with strips of forest; it is here that our lineage took its first steps.

It must be remarked that the drying trend in the territories East of the GRV was gradual but with distinct periods of accelerated drying. This resulted first in the fragmentation of the existing forests (after 6 MYA) and later in the formation of extended grasslands (around 3 MYA or a little later). The repercussions of these environmental changes are clearly visible in the history of human evolution in terms of both habitat fragmentation (favorable to the emergence of new species) and selective pressure. In fact, it was just around 6 MYA that the human lineage separated from that of the chimpanzees, but it was only after 3 MYA that the essential divergence that led to the emergence of the genus Homo occurred.

Over the past couple of decades, the remains of possible earliest ancestors of the human lineage have appeared on the scene. Taken together, they cover the original time span of our history, ranging from less than 7 MYA to more than 4 MYA. They include three genera (and related species) of still hypothetical bipedal apes and ancestors of ours: Sahelanthropus, Ardipithecus, and Orrorin. Let’s start with the most ancient of them. In 2002 Nature published the preliminary description, taxonomic attribution, and phylogenetic interpretation of a skull found in Chad. This fossil specimen was attributed to a genus and a species hitherto unknown: Sahelanthropus Tchadensis (nicknamed toumaï by its discoverers). The skull, almost complete, and a few other remains were found in the area of Lake Chad, now a desert thousands of miles west of the GRV. The chronology, not very precise (deduced from the faunal assemblage only), was based on a strati-graphic horizon ranging between 7 and 6.5 MYA in terms of biochronology. Since then, the morphology of this skull has been the object of numerous studies, but not all paleoanthropologists believe this is an ancestral form of the human lineage. If its age were confirmed, it would exceed the limit set by the molecular clock, which corresponds to about 6 MYA. We could then assume that the calibration based on genetic data is not precise and the separation of our evolutionary line from chimpanzees should be moved further back.

Two years earlier another new species (and new genus), Orrorin tugenensis, had been suggested as a possible ancestor of the human lineage, although this hypothesis was based on a few fragmentary fossil remains found in deposits of the Tugen Hills (Kenya) dated to about 6 MYA. If the cranial and dental remains of Sahelhanthropus did not allow a reliable diagnosis on its bipedalism (the “trademark” of our evolutionary line), those of Orrorin—a couple of well-preserved portions of femur, in particular—suggested a rather advanced bipedalism. Only the discovery of further remains and/or new analyses of those already discovered may shed light on this leading character in the early history of our origins.

Let’s finally introduce the genus Ardipithecus, discovered in Ethiopia in the area known as Middle Awash, two species of which have been known to us for more than ten years. The oldest one, Ar. kadabba, is represented by a very small sample of fragmentary remains with ages ranging between 5.8 and 5.2 MYA; in this case, too, we should suspend our judgment, given the incompleteness of the findings. On the other hand, another species—reliably dated to 4.4 MYA and named (in 1994) Ar. ramidus—has been identified through several fossil remains, including many bones from a single skeleton. It is the oldest skeleton among those (actually very few) available to paleoanthropologists, and the media nicknamed it “Ardi.” Thanks to advanced analyses, based also on X-ray imaging, the different bones were described in detail in several papers that made up an entire issue of the international journal Science (October 2, 2009). What emerged was a mixed picture in which, notwithstanding the persistence of ape-like features—the skull, body proportions, and many anatomical details (such as the opposable big toe)—the evidence suggested placing this species at the roots of our evolutionary tree. Such evidence included some dental traits and, even more importantly, bones of the pelvic girdle that are characteristic of a bipedal ape.

New research will add more fossils, reliable data, and better interpretations to the evidence gathered in recent years. Anything related to the first bipedal apes is of paramount interest to both the specialists and the public, as it concerns the origin of an evolutionary trajectory that millions of years later would lead to the emergence of our own species.

Australopithecus & Friends

We know Australopithecus much better than the previous hominids. Remains of at least four species of this extinct genus have been found. Not counting some uncertain (A. bahrelghazali) and controversial (A. garhi) cases, the most reliable species at the moment are, in chronological order, A. anamensis, A. afarensis, A. africanus, and the most recent, A. sediba.

A. anamensis is the most ancient Australopithecus specimen, since the fossils attributed to this species—from both Kenya (Lake Turkana) and Ethiopia (Middle Awash)—are dated between 4.2 and 3.9 MYA. Its remains well document both bipedal locomotion and other characteristics, mostly dental, that are typical of the genus Australopithecus. These and other traits are more clearly expressed in A. afarensis, the species that includes the famous skeleton known as “Lucy” (AL 288-1). In fact, this is the best-known variety of Australopithecus, thanks to a considerable number of fossil finds distributed across various sites in Ethiopia (e.g., Hadar) and Tanzania (Laetoli) that span a long time period, between approximately 4.0 and 3.0 MYA. The footprints of three bipedal creatures, older than 3.5 MYA, that remained impressed in a layer of volcanic ash found at Laetoli are also credited to A. afarensis.

The number and variety of fossil remains attributed to A. afarensis allows us to address issues related to the variability of the species and to clarify some aspects of biology and behavior that are extendable to the so-called australopithecines as a whole. These were bipedal apes of medium-large size (just over 5 feet tall, weighing around 35–40 kilograms) that can be easily distinguished from present-day apes, although they had a relatively small cranium (their brain size did not exceed, on average, half a liter) and a rather large face projecting forward, with developed jaws. They did not have the dental proportions of other Hominoidea (that have large protruding incisors and canines, but relatively small premolars and molars); instead, the species of the genus Australopithecus—and even more so those of the genus Paranthropus, which we will meet soon—had relatively small front teeth, non-protruding canines, and large back teeth.

Another important aspect concerns the upright bipedal posture, a model of locomotion very rare, if not absent, among extant and extinct primates. The late Miocene apes experienced forms of bipedalism, and also present-day chimpanzee can do this for short distances; but the human lineage, including australopithecines, has a gait and body shape that are unique.4 Bipedalism has affected the entire body, changing nearly any part of the skeleton. The pelvic girdle was particularly affected, with crucial consequences on several aspects related to birth and in evo-devo relationship with brain development, which will appear with the evolution of the genus Homo (as we shall see in chapter 4). Furthermore, the upright posture freed the upper limbs from their locomotion commitments, and hence the hands of the previously arboreal primate became capable of manipulating objects with particular dexterity and subsequently producing archaeologically visible artifacts.

In addition to the australopithecines from eastern Africa (A. anamensis and A. afarensis) and other similar taxa that deserve further attention,5 some species of Australopithecus have been discovered in the southern part of the continent. A. africanus has been found in the sites of Taung, Sterkfontein, and Makapansgat in South Africa. Owing to the characteristics of these deposits (karst fills), it is not easy to attribute precise dates to the remains of this species, but we know they cover a period between about 3 and 2.5 MYA. In this case, too, the fossil remains are of several individuals, and thus we know quite well the characteristics of A. africanus. Nevertheless, its exact phylogenetic position remains to be confirmed. Some interpret this species as the last Australopithecus form preceding the genus Homo; others believe its geographical location disproves this hypothesis, since the oldest evidence of Homo comes from eastern (and not southern) Africa, as we shall see shortly.

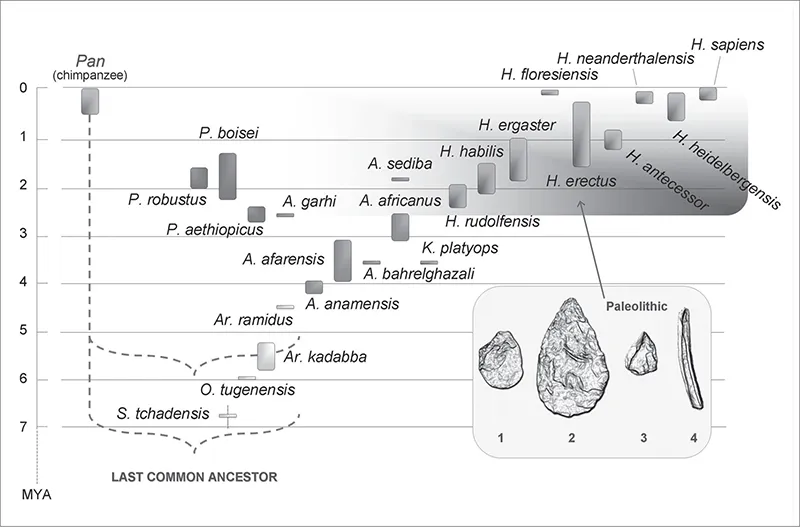

FIGURE 1.1

Extinct hominin species described on the basis of the fossil record. These species connect H. sapiens to extant apes through a bushy path lasting 5–6 million years. The figure includes also a schematic representation of the Paleolithic “modes.” LEGEND: S.= Sahelanthropus, O.= Orrorin, Ar.= Ardipithecus, A.= Australopithecus, K.= Kenyanthropus, P.= Paranthropus, H.= Homo. Redrawn from G. Manzi, L’evoluzione umana (Bologna, It.: il Mulino 2007).

This debate has been recently reinvigorated by the discovery of the remains of at least four skeletons (over 200 fossils so far) attributed to another australopithecine, A. sediba, a species known to the public only since 2010. The numerous and well-preserved remains come from the site of Malapa, 45 kilometers from Johannesburg, South Africa, and are well dated to about 1.9 MYA. The combination of some characteristics common in Australopithecus (e.g., the size of the molars) and others closer to the genus Homo (e.g., the conformation of the pelvic bones) makes these findings a discovery of enormous interest. In fact, A. sediba might play a special role in the origins of our own genus....

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Prologue

- 1. Human Origins: Just a Primer

- 2. How (Many Millennia) Old Are You?

- 3. What Bad Weather in the Pleistocene!

- 4. New Microscopes and Quantitative Paleontology

- 5. Reading Molecules in Fossils

- 6. Stories of Molecules and Hominids

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Glossary

- Further Readings

- Index

- About the Authors