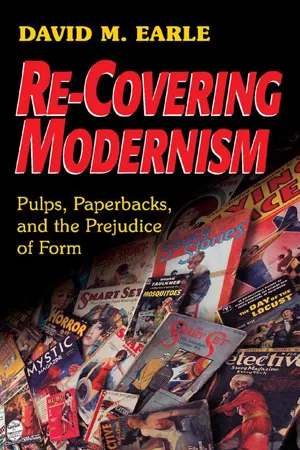

eBook - ePub

Re-Covering Modernism

Pulps, Paperbacks, and the Prejudice of Form

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the first half of the twentieth century, modernist works appeared not only in obscure little magazines and books published by tiny exclusive presses but also in literary reprint magazines of the 1920s, tawdry pulp magazines of the 1930s, and lurid paperbacks of the 1940s. In his nuanced exploration of the publishing and marketing of modernist works, David M. Earle questions how and why modernist literature came to be viewed as the exclusive purview of a cultural elite given its availability in such popular forums. As he examines sensational and popular manifestations of modernism, as well as their reception by critics and readers, Earle provides a methodology for reconciling formerly separate or contradictory materialist, cultural, visual, and modernist approaches to avant-garde literature. Central to Earle's innovative approach is his consideration of the physical aspects of the books and magazines - covers, dust wrappers, illustrations, cost - which become texts in their own right. Richly illustrated and accessibly written, Earle's study shows that modernism emerged in a publishing ecosystem that was both richer and more complex than has been previously documented.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Re-Covering Modernism by David Earle,David M Earle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Smart Set, Modernism, and the Expanded Field of Magazine Production

How to Appear Sophisticated

1. Express yourself in free verse, the crazier and the more meaningless the better.

2. Refer familiarly to H.L. Mencken, Theodore Dreiser, D.H. Lawrence, the intelligentsia, and your bootlegger.

3. Interlard your stuff with French phrases, such as may be found in any First French book.

4. Allude often to Freud and play up his jargon.

5. Emit an occasional cynicism about books, jakes, yokels, morons, etc.

—Oakland Tribune, 13 April 1924.1

MODERNISM is sweeping the intelligent world. You find it in music, in the arts, in literature. You can’t ignore it. Yet, what do you know about it? What do you think about it?

You won’t always understand modernism. But you should at least be able to appreciate it.

There is a way, an easy way, to know and enjoy the newest schools of modern thought and art … . A forum where the most brilliant minds of two continents exchange their ideas.

This forum is the magazine Vanity Fair […]

Vanity Fair always presents the modern point of view … the sketchy, sophisticated, half gay, half serious outlook on life …

It is, in a true sense, the mirror of modernity.

Subscribe Now and assure yourself a fresh and modern point of view for all of 1929 …

1 Year Vanity Fair $4.00

—Subscription Ad, Vanity Fair Magazine, 1927

Academic criticism is grounded firmly upon the doctrine that all literary values may be established scientifically and beyond cavil, as the values of hog fodders, say, may be established – in other words, that criticism is an exact science, like thermo-dynamics or urinalysis.

—H.L. Mencken. The Chicago Tribune, January 3, 1925.2

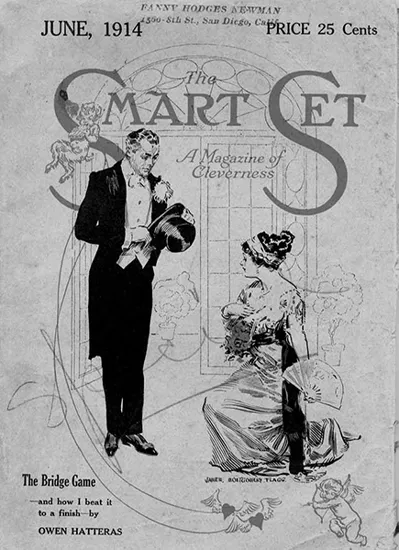

By September 1915 the prospects of H.L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan were on the up-swing. The two young journalists were quickly becoming the darlings of the literati, their reputations resting on years of no-holds-barred criticism in the pages of The Smart Set magazine, most of which decried the stagnant state of American culture and the arts. But now, after a long series of difficult editors and cantankerous owners, The Smart Set had been sold for debts owed to Eugene Crowe, paper manufacturer and publisher of Field and Stream—and Mencken and Nathan had been appointed joint editors with carte-blanche to turn The Smart Set from its position as a light hodgepodge of clever fiction with high-society trappings into a sophisticated forum of artistic fiction and criticism. And for the first time the two editors were actually making money. Hence Mencken, writing book reviews in his Baltimore home, was unprepared for the late night, frantic phone call from Nathan summoning him immediately to the magazine’s New York offices.

It seems that that day an agent of the local vice society, working undercover, had walked into the office at 331 Fourth Avenue and talked the advertising manager Irving T. Myers into giving him a copy of the magazine that Nathan and Mencken edited. This in turn quickly resulted in a raid upon the offices by John Saxton Sumner, confirmed Son of the American Revolution, member of the Founders and Patriots of America, and the newly appointed secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Sumner, implementing the Federal Anti-Obscenity Postal Statutes, had Myers, as well as the magazine’s publisher, Eltinge F. Warner, arrested on obscenity charges.

The vice societies—or “Comstocks,” as Mencken had labeled them in honor of Anthony Comstock, Sumner’s predecessor and author of the postal laws that sported his name—were a powerful force in the first few decades of the twentieth century, again and again browbeating publishers to withdraw questionable books from circulation. 1915 was just the beginning of Sumner’s career, and within six months he would succeed in suppressing Stanislaw Przybskewski’s Homo Sapiens and more notably Theodore Dreiser’s The “Genius.”

Nathan and Mencken were worried for their publication, but were in no danger of prosecution since, even though they edited the magazine in question, their relationship to it was not made public, for it was not The Smart Set that had been the object of the raid but the Parisienne—a tawdry pulp rag that Mencken and Nathan had started solely to support themselves and the floundering—yet more serious—Smart Set (see Figure 1.1). According to Mencken, the French name and continental milieu of the Parisienne had been chosen simply to cash in on the Francophilia that proliferated in the States in the early days of World War I, and, unstated by Mencken yet obvious, for the promise of risqué bohemianism and romance that France held for a provincial country where Comstockian Puritanism held so much sway. Instead of using their own names, Mencken and Nathan signed all Parisienne correspondence with a series of French-sounding noms-de-plume because the last thing that the editors wanted anyone to know was that they, the high priests of American culture, were responsible for putting together a magazine that overtly pandered to popular taste.

In his memoirs, Mencken notes that “the pulp magazines were just then beginning to make money and we resolved to set one up. If the broken down hacks who were operating some of the most successful of them could get away with it, then why not such smart fellows as Warner, Nathan and me…even if our proposed pulp failed, the net loss would not be large, and if it made a hit with the morons it would not only pay well in itself, but also further reduce the overhead on The Smart Set.”3 And the morons came through. From the very first issue, the Parisienne proved to be an assured moneymaker, netting the two editors, as well as publisher Warner and owner Crowe, a considerable profit.

Fig. 1.1 Smart Set, June 1914 © 1914 John Adams Thayer Corporation

The obscenity charge was indeed worrisome. If they were indicted, it would soon put an end to this lucrative venture as well as damage the social standings of Crowe, Warner, and Myers. Although Mencken and Nathan found considerable glee in the idea of Myers and Warner sweating it out for a magazine they really had no responsibility for, they were leery of upsetting Crowe who could easily curtail their plan for turning The Smart Set into a trail-blazing literary review.

But Crowe, an old-time magazine mogul with influence reaching to Tammany Hall, made sure that nothing would happen to his cash cow. According to Mencken, at the trial the charges were dropped due to Crowe’s influence and $500 cash slipped to one of the three presiding judges. It was a lesson for Sumner, and one that he must have taken to heart—he would rarely lose such cases over the next few years. This was also the first in a series of confrontations between Mencken and the vice societies, and Mencken would rarely pass up the chance to bad-mouth the Puritanism that plagued American arts over the next decade.

At work in the preceding interaction are a series of submerged tensions and dichotomies that would become emblematic—and problematic—to the growth and reification of modernism as a canonized, defined movement. These tensions concern the dynamics of cultural stance and definition, of hidden economics and patronage, of marketing schemes, sensationalism, and audience reception. The fact that Charles Sumner approached both modernist and pulp fiction alike—he would soon be instrumental in censoring the serialization of James Joyce’s Ulysses in The Little Review—or that a magazine like The Smart Set, which introduced thousands of American readers to Ezra Pound and Joyce, shared authors with a series of Mencken and Nathan–edited pulp magazines, hints at popular aspects of elite literature that have long been ignored. It also divulges a multilayered prejudice regarding the form of literature by forcing the question of why certain media and formats have lended themselves to canonization while others have been kept out of the archives. The Little Review, for example, has been reprinted and digitized, collected and studied while The Smart Set has barely been more than a footnote in the history of literature despite an impressive list of authors and editors. And the Parisienne has been wholly neglected.

The Smart Set as Modernist Venue

What are we to do with The Smart Set? Over the course of its 30-year run it was a high-society fiction and gossip magazine, a general fiction magazine, a forum for daring and modernist fiction, and a women’s true confession magazine. Critics have categorized it as both an avant-garde little magazine and a pulp magazine. Ezra Pound considered it “frivolous,” yet he constantly submitted manuscripts and introduced authors to its editors. The magazine’s composition even during its most critically acclaimed period was uneven, publishing highbrow fiction as well as authors who were famous in the all-fiction pulp magazines. For decades, The Smart Set lay forgotten. As the definition of modernist literature became canonized and unified, The Smart Set fell under the radar of critics and cultural historians. With the recent revitalized interest in both print culture and the expanded portrait of modernism, there seems to be revitalized interest in the magazine: the Modernist Journals Project has given it high priority for digitization, there will be a chapter dedicated to it in Oxford University Press’s forthcoming three volume Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, and there is at least one unpublished dissertation on it.4 The small body of existing work on the magazine provides a tempered but still partial portrait by privileging the modernist and elite authors or only Mencken’s and Nathan’s role, rather than the larger percentage of popular, overlooked, or noncanonized authors and fiction. This dynamic of exclusion, which involves an entire matrix of substantiation—economic, social, political—can be seen in Frederic Hoffman’s influential study of little magazines (1947), which includes The Smart Set—though few critics have expanded upon or questioned this definition. The little magazines are traditionally thought of as the venue for modernism. They were usually short-lived, poorly financed, even more poorly circulated, small run magazines put out by and for the intellectual and artistic avant-garde; they were often politically left magazines with culturally radical overtones or culturally radical magazines with politically left overtones. Circulation rarely went over a few thousand and, in most cases, over a few hundred. Being a “pure” product of the avant-garde, they are traditionally defined as beyond the taint of commercialism—a defining trait that even influenced their very form and physicality (though this definition has come under revision in recent years as critics have looked to expand the venues of modernism to newspapers, trade journals, film, and radio, and popular magazines).

Such historians of The Smart Set discount almost entirely the magazine’s popular aspects, or simply regulate them to the non-Mencken years, even though it was this very popularity that made the magazine attractive to modernist entrepreneurs like Ezra Pound. It is this same dynamic of exclusion that forced The Smart Set under the radar of critics, privileging magazines like The Little Review and The Dial that were easier to codify and more obviously in keeping with the idea of what an avant-garde periodical should be.

We, as enlightened and politically savvy critics and readers, have come to realize that all those old definitions of modernism, molded by the hands of not only dead white male authors (Joyce, Pound, Lewis, Ford) but dead white male critics (Kenner, Cowley, Wilson), are slanted, partial, and even self-serving. We know this, as current criticism continually attests by uncovering the important modernist voices and roles of women, people of color, lower classes, and other positions that undermine monolithic modernism. Yet our study of the forms and venues of modernism is still restrained to a certain type of publication, excluding those magazines that have a taint of the popular about them. This chapter (and the study in general) considers how The Smart Set meets many of the requirements of modernist canonization while simultaneously being an outlet for popular fiction, hence divulging a popular modernism. Establishing The Smart Set as an obvious and fluid outlet of modernism is purposefully unga...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Smart Set, Modernism, and the Expanded Field of Magazine Production

- 2 Pulp Modernism

- 3 Lurid Paperbacks and the Re-Covering of Modernism

- Bibliography

- Index