eBook - ePub

Speaking for the Enslaved

Heritage Interpretation at Antebellum Plantation Sites

- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Speaking for the Enslaved

Heritage Interpretation at Antebellum Plantation Sites

About this book

Focusing on the agency of enslaved Africans and their descendants in the South, this work argues for the systematic unveiling and recovery of subjugated knowledge, histories, and cultural practices of those traditionally silenced and overlooked by national heritage projects and national public memories. Jackson uses both ethnographic and ethnohistorical data to show the various ways African Americans actively created and maintained their own heritage and cultural formations. Viewed through the lens of four distinctive plantation sites—including the one on which that the ancestors of First Lady Michelle Obama lived—everyday acts of living, learning, and surviving profoundly challenge the way American heritage has been constructed and represented. A fascinating, critical view of the ways culture, history, social policy, and identity influence heritage sites and the business of heritage research management in public spaces.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Speaking for the Enslaved by Antoinette T Jackson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

HISTORY, HERITAGE, MEMORY, PLACE

Heritage is not our sole link with the past. History, tradition, memory, myth, and memoir variously join us with what has passed, with forebears, with our earlier selves. Yet the lure of heritage now outpaces other modes of retrieval.

—David Lowenthal (1996:3), Possessed by the Past

That heritage can be sustained only by a living community becomes an accepted tenet. To sustain a legacy of stones, those who dwell among them also need stewardship.

—David Lowenthal (1996:21), Possessed by the Past

HERITAGE

Heritage is being discussed everywhere it seems, and typically with passion. Solidly part of the public domain of inquiry, it is a subject that most people have an intimate relationship with—academics, public officials, dignitaries, elders, and youth alike. The journey to know our heritage represents a profound desire to see ourselves in the continuum of history on a family, community, national, or global level. It is a quest to know more about ourselves and to share that knowledge with others through a variety of means. Questions such as these are common: Who am I? What stories, memories, and what traditions are important to my family and within my community? Each generation asks how these stories are reflected in the public record and by whose authority.

But what is heritage exactly? How is it defined, expressed, and shared? Can my desire to express my heritage coexist with your right to express yours? What happens when multiple expressions and ways of expressing heritage collide in public forums or, perhaps even more challenging, fail to even exist in public venues and forums?

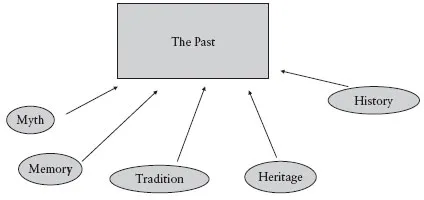

There are numerous definitions of heritage (Chambers 2006; Herbert 1985; Howard 2003; Karp, Kreamer, and Lavine 1992; Lowenthal 1985, 1996). For example, in his book Possessed by the Past David Lowenthal (1996) offers several ways of thinking about heritage. First, he defines the difference between history and heritage, which he claims is a vital distinction—“History explores and explains pasts grown ever more opaque over time; heritage clarifies pasts so as to infuse them with present purposes” (Lowenthal 1996:xi). Then, in the passage that I use to open this chapter, Lowenthal goes on to place heritage in the context of other ways of knowing and experiencing the past, an important organizing perspective. Fath Davis Ruffins (1992) critically elaborates on ways of knowing and interpreting the past. She examines the very idea of “the past” in the context of modes of interpretation—history, memory, and mythos—specifically applying her analysis to African-American preservation efforts. She writes: “One way to think about the past as being different from history is to see historical interpretation as a snapshot of the past” (Ruffins 1992:509). Figure 1.1 graphically illustrates the positioning of heritage in the context of other ways of knowing the past as elaborated on by Lowenthal (1996) and Ruffins (1992).

Building on definitions outlined by Ruffins (1992) and Lowenthal (1996), I think it is important to critique what is meant by the past and to consider the distinction between history and heritage. Ruffins states that “historical interpretation of the past is made out of selections of the past by people in the present in order to help them [to] understand both the past and the present” (1992:510). I define history as a story about the past—one of many that could be told at any given moment. The skill of the history maker is determined by the evidence used to tell the story as judged by the stakeholders that sanction its production. And history, as Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1995) would have us note, is not only what happened but also what is said to have happened. The power is in the production and reproduction of the story in the present and the story’s relevance to those affected.

Figure 1.1 Engaging the past (courtesy of author)

I define heritage as anything a community, a nation, a stakeholder, or a family wants to save, make active, and continue in the present. Heritage is one way of engaging in or assessing the past (Figure 1.1). It is our living connection to history in the present moment—a connection that can be expressed in variety of ways, such as through rituals, traditions, stories, songs, memories, and myths. Heritage is both tangible (material cultural remains such as buildings, monuments, tombs, and bridges) and intangible (such as folkways, kinship, language, music, laboring practices, and artisan skills). Although more emphasis has been placed on preserving tangible aspects of heritage and of the past, there is increasing recognition of the importance of preservation of intangible cultural heritage as an important link to the past, particularly seen in the construction of internationally sanctioned conventions or guidelines directed at this goal. In 2003, for example, UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) proposed Conventions for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (UNESCO 2003). Like the 1972 UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972), it deals with cultural heritage and its protection. However, as of the printing of this book, the 2003 Convention is still awaiting ratification by a significant body of UNESCO member states, including the United States.

Erve Chambers (2006) defines two categories of heritage—public and private (personal). Private heritage is described as tangible and intangible items or things that individuals inherit and pass down to later generations. It consists of information expressed through daily routines and actions, which are not necessarily sanctioned by an official authority (for example, the National Park Service). Essentially it is the way things are done in your family, your organization, or your neighborhood, which is passed on to the next generation or group of participants through symbols, rituals, and language, for example. Public heritage is the sharing and transmission of recorded information about things, such as a place, an event, or a person that we may have no direct experience with knowing. It is typically information presented and shared by “official” or sanctioned keepers of history, such as museums, libraries, and historical societies and historical preservation boards in the form of written text, graphics, pictures, selected artifacts, and designated structures. By collecting ethnographic and ethnohistorical data (for example, oral histories, community maps, housing statistics, cemetery data, civic records, census data) across diverse segments of families, communities, and neighborhoods, covering a range of periods of time, one sees a public profile of the history and heritage of a community, of a nation (for example, the United States), emerge that is more representative of the breadth and depth of experiences and memories of all people that call that place home.

Finally, we must recognize the distinction between heritage as a cultural asset for conservation and preservation, such as viewed by groups focused on cultural heritage management, and the use of heritage as a product or commodity for consumption and sale from a business perspective, such as the case in heritage tourism. It is a distinction that is critically engaged in the book Cultural Tourism by McKercher and du Cros (2002). Specifically, they underscore the need for groups invested in heritage from either perspective—conservation or consumption—to work in partnership or at least to strive to communicate more effectively during the planning and implementation phases of heritage projects in communities in which they work.

In all cases, heritage involves the construction of a story about the past that affects the present. Slavery, for example, plays a central role in the history and heritage of the United States. However, this is an underrepresented story when it comes to the construction of national heritage. In her article Tourism and National Heritage (U.S.) Allison Carter outlines links between national heritage, race, and place in terms of African-American communities and history. She writes: “Hence from its beginnings slavery, race, and place are essential components of any depiction of national heritage in the United States and as such become sites of contested meanings. African-American heritage tourism forces revisiting of conflicting discourses about the meaning of African-American experience in U.S. history, as well as the meaning of U.S. history itself” (Carter 2008:134).

RESEARCHING PLANTATIONS AND POSTBELLUM PLANTATION COMMUNITIES

A large body of scholarly work has been published on the transatlantic slave trade, plantation life, and slavery in the Americas, primarily by historians (Berlin 1998; Blassingame 1979 [1972]; Burton 1985; Eltis, Lewis, and Sokoloff 2004; Genovese 1976 [1974]; Morgan 1998; Phillips 1946 [1929]; Rawick 1972; Ruffins 2006; White 1985; Wood 1974). Historical archaeologists have also contributed to scholarship on plantations, in many cases linking African agency to the material record (Davidson 2008; Epperson 1999; Fairbanks 1974; Ferguson 1992; Leone and Potter 1988; McDavid 2007; Orser 1998, 2004, 2007; Shackel, Mullins, and Warner 1998; Singleton 1985, 1999, 2000; Vlach 1993; Wilkie 2000).1 However, culturally oriented anthropological studies focused on African lifeways in antebellum and postbellum communities in the southeast region of the United States have been undertaken by a small group of scholars (Guthrie 1996; Jackson 2004; Jones-Jackson 1987; Mitchell 1999).

This analysis compels an expansion of the list of possible sources of information about plantations and slavery to include not only measurable facts that can be retrieved/excavated and interpreted but also less easily measurable sources of information—at least from a positivist perspective—for developing explanations. For example, oral history and ethnographic interview data can bring to light what Cooper, Holt, and Scott in Beyond Slavery characterize as the “messy, contradictory worlds that slaves and slaveowners created” (2000:7).

I draw on research I conducted in postbellum plantation communities in the U.S. South.2 These communities challenge assumptions about American history and heritage constructed in the context of the transatlantic slave trade. By giving primacy to knowledge shared by enslaved Africans through their descendants, I document how Africans and people of African descent (identified as “black”) developed ways of living in antebellum plantation spaces and created a future for their communities and families. Integrating archival data collection with qualitative research methods—such as ethnography, ethnographic interview, oral history, and participant observation—my research proposes that Africans in America engaged in various processes of culture and identity formation (including heritage preservation) through everyday acts of living—working, establishing families, raising children, caring for elders, and growing, harvesting, cooking and sharing food.3 At the same time, they actively used resources, generated knowledge systems, developed communities, and exhibited behavior aimed at foiling, countering, and navigating within a Eurocentric system of power and control designed to limit their autonomy (Davis 1983 [1981]; Gutman 1976; Jackson 2004, 2009).

Interpreting the history and heritage of African communities in plantation spaces through perspectives shared by descendants—through their stories, expressions, critiques, and lived experiences—conveys what is best described by Patricia Hill Collins as an “outsider within” approach to knowing (Collins 1991:11). Participating in day-to-day activities seemingly unrelated to the transatlantic slave trade, descendants of enslaved Africans today and others (including descendants of plantation owners) often embody deeper, more complex meanings and associations with former antebellum plantation sites. Their knowledge, which has often been subjugated (Collins 1991; Foucault 1980 [1972]), is an important addition to the scholarly discourse and will help to reinterpret the practice of slavery in America in new, more complex ways. When scholars make these bodies of knowledge visible in the public record, their ways of knowing and thinking about African communities in plantation spaces are expanded. Anthropologists Ira E. Harrison and Faye V. Harrison call the systematic unveiling and recovery of subjugated knowledges a critical aspect of any transformative anthropological project, especially with respect to African Americans (1999). By offering a link to enslaved ancestors through intergenerational conversations—communication and direct engagement with parents, grandparents, and great grandparents—their stories are a means of speaking for the enslaved and providing a more nuanced interpretation of U.S. American history.

SLAVERY AND THE RACIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC MEMORY

New voices have emerged to debate the proper place of slavery in the larger history of the United States. New institutions devoted to slavery as a subject will have to place themselves definitively within this contentious environment so as to garner financial and other forms of public support. In that complex process, a new synthesis may appear that honors both the suffering of the enslaved and their contributions to American society.

—Fath Davis Ruffins (2006:426–27), Revisiting the Old Plantation: Reparations, Reconciliation, and Museumizing American Slavery

When the U.S. Constitution was drafted and signed at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787 by fifty-five delegates, one of the primary areas of dispute for the (now politicized) “Founding Fathers” was slavery. How should the issue of slavery be addressed in a document founded on freedom? Delegates from South Carolina and Georgia, strong advocates of the slave trade, declined ratifying the Constitution until their demands for protection of the institution of slavery were met. In response, a compromise was reached. It included a twenty-year extension of the slave trade in America, a fugitive slave law, and a provision that each slave be counted as only three-fifths of a person for the basis of taxation and political representation. Governor Charles C. Pinckney, a delegate from South Carolina, was pleased with the compromise and went on to sign the Constitution solidifying the union or creation of the United States of America.

As a result the compromise, the U.S. Constitution, as written and signed by the Founding Fathers of the United States, was secured around the provision of slavery. At the time of signature there were expressed concerns by many delegates outside the Southern colonies that this compromise, which incorporated slavery into the very foundation of the Constitution, would prove to be, as stated by George Novack, “the chief crack in the cornerstone of the new Republic, a crack which in time might widen to a fissure capable of splitting the union apart” (Novack 1939:345).

The Civil War, a war between states, families, and communities in the United States, was fought over the institution of slavery and proved to be the fissure that nearly split the union apart. This fissure, the issue of slavery, has impacted representations of national heritage in the public forum.

Public perceptions of antebellum and postbellum plantations are influenced by depictions that posit the centrality of a master-slave dynamic without critique. Typical representations of this dynamic, such as the Gone with the Wind trope (Mitchell 1993 [1936]) and plantation depictions in popular epics such as North and South (Jakes 1982) and Queen (Haley and Stevens 1993), foreground an elite, white male plantation owner and marginalized black servants as key caricatures. In marketing this simplistic representation of racial hierarchy and place, black identity is fixed to notions of social place constructed around arbitrarily defined racial markers in which people identified as “white” are categorically assigned a higher status than people racialized or marked as “black” (or other than white), who are depicted as lacking agency.

Although contemporary scholarship widely negates race as a means of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations and Tables

- Foreword by Paul A. Shackel

- Preface

- Chapter 1 History, Heritage, Memory, Place

- Chapter 2 Issues in Cultural Heritage Tourism, Management, and Preservation

- Chapter 3 Roots, Routes, and Representation: Friendfield Plantation and Michelle Obama’s Very American Story

- Chapter 4 Jehossee Island Rice Plantation: A World Class Ecosystem—Made in America by Africans in America

- Chapter 5 “Tell Them We Were Never Sharecroppers”: The Snee Farm Plantation Community and the Charles Pinckney National Historic Site

- Chapter 6 The Kingsley Plantation Community: A Multiracial and Multinational Profile of American Heritage

- Chapter 7 Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index

- About the Author