- 255 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

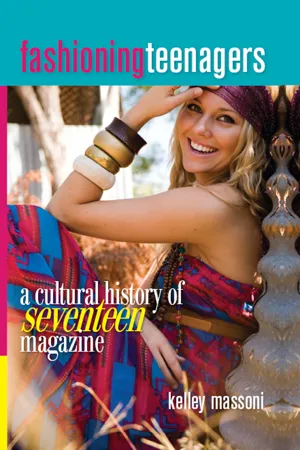

About this book

Founded in 1944 by Helen Valentine, Seventeen magazine was the first modern "teen magazine." An immediate success, it became iconic in establishing the tastes and behaviors of successive generation of teen girls covering the last half of the 20th century. Kelley Massoni has written the first cultural history of the origins of Seventeen and its role in shaping the modern teen girl ideal. Using content analysis, interviews, letters, oral histories, and promotional materials, Massoni is able to show how Seventeen helped create the modern concept of "teenager." The early Seventeen provided a generation of thinking young women with information on citizenship and clothing, politics and popularity, adult occupations and adolescent preoccupations, until economic and social forces converged to reshape the magazine toward teen consumerism. A chapter on the 21st century Seventeen brings the story to the present. Fashioning Teenagers will be of interest to students of popular culture, sociology, gender studies, mass media, journalism, business, and American studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fashioning Teenagers by Kelley Massoni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER | 1 |

The Birth of the Teen Magazine:

Delivering Seventeen Magazine to the U.S. Marketplace

Out of this complex social maze has come a new classification of human beings—the teen-ager. As problems have multiplied in number and severity, contemporary Americans, reaching an age which fifty years ago would have represented adulthood, are not prepared to assume the responsibilities of an adult in the modern world. A longer period of preparation—an apprenticeship to maturity—is necessary. [“Too Young to Marry?” Seventeen, November 1949, 142]

Teenager. Today, the word immediately elicits images and stereotypes. Raging hormones and bare midriffs. Tattoos and body piercings. Acne and cosmetics. Valley girls and mall rats. As an integral part of contemporary Western culture, teens inhabit our environs, our media, our psyches. Teens, it seems, are everywhere!

But teens have not always been everywhere; in fact, they are actually a recent cultural construction. G. Stanley Hall is most often credited with introducing the idea of adolescence as a specific (and troublesome) state of life through his widely read 1904 psychology text, Adolescence.1 Historians report that the word itself, in its first incarnation as the hyphenated “teenager,” didn’t become a part of the popular lexicon until the late 1930s and early 1940s.2 The New York Times, for example, first used “teen-ager” on October 18, 1942, in an article that documented the sale of war stamps to high school girls at Saks, the New York City department store.3

It is quite apropos that this first editorial reference mentions “teen-age” girls in relation to a consumer event at a department store, since retailers and advertisers signaled their awareness of this age group long before other media. In fact, advertisements for department store “teen shops” and teenspecific department store areas began appearing in newspapers and magazines nearly a decade before any editorial mention of teen-agers. The first teen-targeted advertisement in the New York Times ran on October 4, 1934, in an announcement for the opening of New York City department store Lord & Taylor’s “new shop for girls of 12, 14, 16.”4 The ad heralded the teen shop as a unique “solution” to a teen apparel “problem”:

“Here you will find clothes that reach a happy compromise between ‘mother’s little girl’ and the ‘I’m grown up’ idea. We have designed suitable things for this difficult in between age […] and we’re calling it the in-be-teen shop.”5

Clothing manufacturers first introduced special teen-size attire in the 1930s. Prior to the 1920s, women who did not sew their own clothes could buy ready-made clothing for their daughters and themselves in either childrens or women’s sizes. In the next two decades, however, retailers and clothing manufacturers became increasingly aware of the sales potential for women of college and high school age. They began to manufacture and market clothing for these two age groups, first with “junior” sizes for older teens and young adult women, and later with “teen” sizes for their younger sisters. Although women’s and juniors’ clothes employed different size ranges (8–20 and 7–15, respectively), they were both cut for a woman’s fuller figure; “teen” wear (sizes 10–16), on the other hand, was produced to fit the leaner, less developed figure of a “budding” woman.6

It was not a coincidence that the decade of the 1940s saw the birth of Seventeen—the first fashion and service magazine targeted to high school age girls—today known as a “teen magazine.” Indeed, the logic of the market explains Seventeen’s conception during the same period that the concept of the American “teen-ager” was emerging. By the early 1940s, retailers had identified a new consumer group in girl teen agers and a corresponding market in teen age girl clothing; Seventeen emerged as a vehicle to bring the two together. Upon its entry into American life, Seventeen became one of the major sources of teen girl culture.

Teen Publications and Seventeen Magazine

The first issue of Seventeen was published in New York City and distributed across the United States in September 1944. While other magazines targeting adolescent girls existed at that time, each differed in significant ways from Seventeen. For instance, Calling All Girls, first published by Parents magazine in July 1941, was geared toward a slightly younger readership—girls referred to today as “preteens” or “tweens.”7 In the 1943–44 edition of The Writer’s Market, a biannual publication for freelance writers that listed editorial descriptions of magazines, Calling All Girls reported that it published material that “appeal[ed] to girls of 9 to 14,” including “some ‘how-to-do’ articles, personality sketches or just informational.”8 Calling All Girls also included comics, fiction stories, and advertisements for clothing, grooming aids, and snacks.

Another competitor in the girls’ magazine market of the early 1940s was The American Girl. Published by the Girl Scouts of America from 1917 through 1979, The American Girl featured short stories and articles deemed “suitable” for teen-aged girls.9 This “suitable” territory covered the lives of people in other countries, grooming advice, and Girl Scout history and current events. The American Girl included advertisements for grooming, medical, and hygienic products; auto and appliance companies; and Girl Scout–affiliated merchandise. Other “girl” magazines of the period were religiously affiliated: The Catholic Girl and Catholic Miss were published for young Catholic women, while Queens’ Gardens marketed itself as appropriate for Christian girls.10

The magazine closest in spirit and strategy to Seventeen was Mademoiselle. Mademoiselle debuted in February 1935 as an alternative for young women ages 18 through 34 who were interested in fashion specifically geared to their (as opposed to their mothers’) age and spending range.11 Subtitled The Magazine for Smart Young Women—“smart” meaning both “intelligent” and “fashionable”—Mademoiselle strove to integrate smartness into the magazine’s mission. Editor-in-chief Betsy Talbot Blackwell’s concern for her readership as “whole persons” was expressed through quality art and fiction.12 Although Mademoiselle ceased publication in 2001, it left behind a legacy of publishing fiction by important writers, including John Cheever, William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, Sylvia Plath, and Truman Capote.

Despite the fact that it was marketed to a slightly older constituency, Mademoiselle could be regarded as Seventeen’s foremother. A 1946 Business Week article listed Mademoiselle as among the “antecedents of the teen-age exploitation” of the ’40s.13 Blackwell, Mademoiselle’s editor from 1937 to 1971, recognized the economic value in identifying a specific audience as a demographic consumer market niche. With the help of Helen Valentine, her promotion director from 1939 to 1944, Blackwell made Mademoiselle successful with both readers and advertisers by targeting upper-and middle-class college-age women—a group with the financial potential to become influential consumers.14 Seventeen entered the magazine market in 1944 as a bridge between existing girls’ magazines (Calling All Girls and American Girl) and young adult women’s magazines (Mademoiselle).

World War II

Seventeen magazine debuted during World War II, a context that shaped both its production and content. During the war, the U.S. government worked with advertisers and media to craft a propaganda campaign directed at women.15 By the time Seventeen began production, the Office of War Information (OWI) and the War Advertising Council were in full swing, urging women to support the war effort through their labor and with their pocketbooks. In order to ensure that women received the “right” messages on a regular basis, the OWI distributed several publications to magazine editors, foremost among them the Magazine War Guide (MWG), which offered monthly suggestions for “war information suitable for use in magazines.”16 Another OWI publication, War Jobs for Women, was distributed to both editors and the public, and listed the many employment opportunities open to women during the war—opportunities that they were encouraged to pursue.17 “It’s a woman’s war right now,” the brochure proclaimed, “and women should be thinking in terms of going to full-time work and carrying along many of their volunteer activities as side lines.”18

Records kept by the OWI indicate that American magazine editors followed the MWG’s directives when choosing material for publication during this period.19 American women also took their marching orders seriously, securing employment outside the home, volunteering for community war efforts, and spending their money frugally and patriotically.20 Women in the workforce were given access to jobs in male-dominated industries that had previously been beyond their reach, earning “man-size” wages that brought more money into their households.21 In turn, many working mothers (both paid and volunteer) transferred their home duties to their teen age daughters, giving their daughters a practical lesson in overseeing a family’s consumer needs and economic resources.22

Although many World War II historians focus on women’s increased employment rates during the war, others note that consumer spending also surged during this period.23 As durable goods became less available, manufacturers and advertisers put their efforts into making and marketing nondurable goods such as clothing. At the same time, teen girls were becoming more and more responsible for spending—both their own earnings and the household income. Thus, the war gave teen age girls a newfound economic power, both individually and as family managers. A 1946 Business Week article marveled at the deep and wide teen consumer market that developed during the war period, measuring it via four indicators: (1) increased spending of teen girls; (2) clothing lines developed just for teen girls; (3) “teen-shops” in which to buy them; and (4) the introduction of the teen magazine genre.24

The war and its aftermath influenced the development of Seventeen magazine, out so too did its creators. The backgrounds and agendas of Seventeen’s first editor-in-chief, Helen Valentine, and publisher, Walter Annenberg, shaped the magazine in its formative years.

Meet Helen Valentine

Helen Rose Lachman was the only child of German Jewish immigrants, Gustave Lachman and Bertha (Kahn) Lachman. Born in New York City on June 25, 1893, Helen spent her childhood—and most of her adult life—in the borough of Manhattan. Her mother was a homemaker, while her father supported the family as an accountant and businessman. Although the family was upper middle class, Helen later alluded to periods of financial instability: “In spite of the fact that we went through many physical changes, financial changes [laugh], quite a bit of drama on the outside, the inside was always calm.”25 When asked about whether her mother did the family cooking, Helen answered, “No. Well, she did sometimes and sometimes we had help. We went through … various [laugh] life stages.”26

Whatever form these life stages took, Helen’s parents were able to send her to a private high school, followed by Barnard College, a prestigious and expensive all-women’s college affiliated with Columbia University in New York City. In reflecting on her early life in her secular Jewish family, Helen says: “I had a very happy, relaxed childhood, a very happy education. I was delighted. I went to the Ethical Culture School, where I was very happy. I went to Barnard, where I was very happy, and I didn’t feel the need to do anything outside at that time at all.”27

Helen graduated from Barnard in 1915 with a degree in English, and in 1920 she married Herbert Irwin Valentine—known to friends and family as “Big Val.” Although Helen reported that she never planned on working outside the home, she engaged in paid employment most of her adult life. As she describes it, after several years of spending her time at home caring for both Big Val and her father (who lived with the newlyweds after her mother’s death), she developed an “itch” that demanded to be scratched: “I began to get a little itchy, wanted to do something, and that’s how I decided that probably the best thing I could do would be to use what little writing ability I had and, in trying to decide which field to go into, I picked a very natural one, which was advertising. It was logical.28”

Helen began her career in 1922 as a copywriter for the Lord &am...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- INTRODUCTION Mirror, Mirror, on the Wall Women’s Magazines and the Modern Beauty Mandate

- CHAPTER 1 The Birth of the Teen Magazine Delivering Seventeen Magazine to the U.S. Marketplace

- CHAPTER 2 Seventeen Magazine at War Teena in the World of Opportunity

- CHAPTER 3 Teena Goes to Market Seventeen Magazine Sells the Ideal Consumer to Business

- CHAPTER 4 Teena Means Business Seventeen Magazine’s Advertisers Court the Teen Girl Consumer

- CHAPTER 5 Seventeen Magazine at Peace Teena Leaves the World, Enters the Home, and Loses Her Mind

- CHAPTER 6 Divorce in the Family Seventeen Magazine Loses Its Matriarch—and Its Way

- EPILOGUE Seventeen Magazine and Teena in the Twenty-First Century

- Notes

- References

- Index

- About the Author